Полная версия

Полная версияCommodore Paul Jones

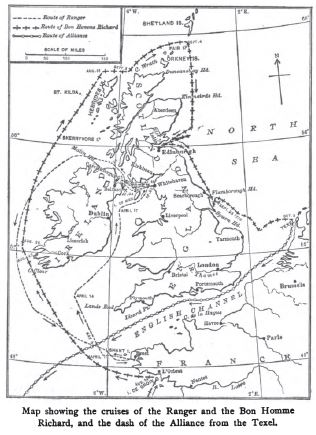

Another gale blew up on the 5th, and heavy weather continued for several days. The little squadron of three vessels labored along through the heavy seas to the northward, passed the dangerous Orkneys, doubled the wild Hebrides, rounded the northern extremity of Scotland, and on the evening of the 13th approached the east coast near the Cheviot Hills. On the 14th they arrived off the Firth of Forth, where they were lucky enough to capture one ship and one brigantine loaded with coal. From them they learned that the naval force in the harbor of Leith was inconsiderable, consisting of one twenty-gun sloop of war and three or four cutters. Jones immediately conceived the idea of destroying this force, holding the town under his batteries, landing a force of marines, and exacting a heavy ransom under threat of destruction.

Although weakened in force by the desertion of the ships, by the number of prizes he had manned, and the large number of prisoners on board the Richard, he still hoped, as he says, to teach English cruisers the value of humanity on the other side of the water, and by this bold attack to demonstrate the vulnerability of their own coasts. He also counted upon this diversion in the north to call attention from the expected grand invasion in the south of England by the French and Spanish fleets. The wind was favorable for his design, but unfortunately the Pallas and the Vengeance, which had lagged as usual, were some distance in the offing. Jones therefore ran back to meet them in order to advise them of his plan and concert measures for the attack. He found that the French had but little stomach for the enterprise; they positively refused to join him in the undertaking, a decision which, by the terms of the concordat, they had a right to make. After a night spent in fruitless argument between the three captains-think of it, arguments in the place of orders! – Jones appealed to their cupidity, probably the last thing that would have moved him. By painting the possibilities of plunder he wrung a reluctant consent from these two gentlemen, and proceeded rapidly to develop the plan.

As usual, not being able to embrace the opportunity when it was presented, a change in the wind rendered it impossible for the present. The design and opportunity were too good, however, to be lost, and the squadron beat to and fro off the harbor, waiting for a shift of wind to make practicable the effort. On the 15th they captured another collier, a schooner, the master of which, named Andrew Robertson, was bribed by the promised return of his vessel to pilot them into the harbor of Leith. Robertson, a dastardly traitor, promised to do so, and saved his collier thereby. On the morning of the 16th an amusing little incident occurred off the coast of Fife. The ships were, of course, sailing under English colors, and one of the seaboard gentry, taking them for English ships in pursuit of Paul Jones, who was believed to be on the coast, sent a shore boat off to the Richard asking the gift of some powder and shot with which to defend himself in case he received a visit from the dreaded pirate. Jones, who was much amused by the situation, made a courteous reply to the petition, and sent a barrel of powder, expressing his regret that he had no suitable shot. He detained one of the boatmen, however, as a pilot for one of the other ships. During the interim the following proclamation was prepared for issuance when the town had been captured. The document is somewhat diffuse in its wording, but the purport of it is unmistakable:

"The Honorable J. Paul Jones, Commander-in-chief of the American Squadron, now in Europe, to the Worshipful Provost of Leith, or, in his absence, to the Chief Magistrate, who is now actually present, and in authority there.

"Sir: The British marine force that has been stationed here for the protection of your city and commerce, being now taken by the American arms under my command, I have the honour to send you this summons by my officer, Lieutenant-Colonel de Chamillard, who commands the vanguard of my troops. I do not wish to distress the poor inhabitants; my intention is only to demand your contribution toward the reimbursement which Britain owes to the much-injured citizens of the United States; for savages would blush at the unmanly violation and rapacity that have marked the tracks of British tyranny in America, from which neither virgin innocence nor helpless age has been a plea of protection or pity.

"Leith and its port now lie at our mercy; and, did not our humanity stay the hand of just retaliation, I should, without advertisement, lay it in ashes. Before I proceed to that stern duty as an officer, my duty as a man induces me to propose to you, by means of a reasonable ransom, to prevent such a scene of horror and distress. For this reason I have authorized Lieutenant-Colonel de Chamillard to conclude and agree with you on the terms of ransom, allowing you exactly half an hour's reflection before you finally accept or reject the terms which he shall propose. If you accept the terms offered within the time limited, you may rest assured that no further debarkation of troops will be made, but the re-embarkation of the vanguard will immediately follow, and the property of the citizens shall remain unmolested."

On the afternoon of the 16th, the squadron was sighted from Edinburgh Castle, slowly running in toward the Firth. The country had now been fully alarmed. It is related that the audacity and boldness of this cruise and his previous successes had caused Jones to be regarded with a terror far beyond that which his force justified, and which well-nigh paralyzed resistance. Arms were hastily distributed, however, to the various guilds, and batteries were improvised at Leith. On the 17th, the Richard, putting about, ran down to within a mile of the town of Kirkaldy. As it appeared to the inhabitants that she was about to descend upon their coast, they were filled with consternation. There is a story told that the minister of the place, a quaint oddity named Shirra, who was remarkable for his eccentricities, joined his people congregated on the beach, surveying the approaching ship in terrified apprehension, and there made the following prayer:

"Now, deer Lord, dinna ye think it a shame for ye to send this vile piret to rob our folk o' Kirkaldy? for ye ken they're puir enow already, and hae naething to spaire. The wa the ween blaws, he'll be here in a jiffie, and wha kens what he may do? He's nae too guid for onything. Meickle's the mischief he has dune already. He'll burn thir hooses, tak their very claes and tirl them to the sark; and wae's me! wha kens but the bluidy villain might take their lives! The puir weemen are maist frightened out o' their wits, and the bairns skirling after them. I canna thol't it! I canna thol't it! I hae been lang a faithfu' servant to ye, Laird; but gin ye dinna turn the ween about, and blaw the scoundrel out of our gate, I'll na staur a fit, but will just sit here till the tide comes. Sae tak yere will o't."

This extraordinary petition has probably lost nothing by being handed down. At any rate, just as that moment, a squall which had been brewing broke violently over the ship, and Jones was compelled to bear up and run before it. The honest people of Kirkaldy always attributed their relief to the direct interposition of Providence as the result of the prayer of their minister. He accepted the honors for his Lord and himself by remarking, whenever the subject was mentioned to him, that he had prayed but the Lord had sent the wind!

It is an interesting tale, but its effect is somewhat marred when we consider that Jones had no intention of ever landing at Kirkaldy or of doing the town any harm. He was after bigger game, and in his official account he states that he finally succeeded in getting nearly within gunshot distance of Leith, and had made every preparation to land there, when a gale which had been threatening blew so strongly offshore that, after making a desperate attempt to reach an anchorage and wait until it blew itself out, he was obliged to run before it and get to sea. When the gale abated in the evening he was far from the port, which had now become thoroughly alarmed. Heavy batteries were thrown up and troops concentrated for its protection, so that he concluded to abandon the attempt. His conception had been bold and brilliant, and his success would have been commensurate if, when the opportunity had presented itself, he had been seconded by men on the other ships with but a tithe of his own resolution.

The squadron continued its cruise to the southward and captured several coasting brigs, schooners, and sloops, mostly laden with coal and lumber. Baffled in the Forth, Jones next determined upon a similar project in the Tyne or the Humber, and on the 19th of the month endeavored to enlist the support of his captains for a descent on Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as it was one of his favorite ideas to cut off the London coal supply by destroying the shipping there; but Cottineau, of the Pallas, refused to consent. The ships had been on the coast now for nearly a week, and there was no telling when a pursuing English squadron would make its appearance. Cottineau told de Chamillard that unless Jones left the coast the next day the Richard would be abandoned by the two remaining ships. Jones, therefore, swallowing his disappointment as best be might, made sail for the Humber and the important shipping town of Hull.

It was growing late in September, and the time set for the return to the Texel was approaching. As a matter of fact, however, though Jones remained on the coast cruising up and down and capturing everything he came in sight of, in spite of his anxiety Cottineau did not actually desert his commodore. Cottineau was the best of the French officers. Without the contagion of the others he might have shown himself a faithful subordinate at all times. Having learned the English private signals from a captured vessel, Jones, leaving the Pallas, boldly sailed into the mouth of the Humber, just as a heavy convoy under the protection of a frigate and a small sloop of war was getting under way to come out of it. Though he set the English flag and the private signals in the hope of decoying the whole force out to sea and under his guns, to his great disappointment the ships, including the war vessels, put back into the harbor. The Richard thereupon turned to the northward and slowly sailed along the coast, followed by the Vengeance.

Early in the morning of September 23d, while it was yet dark, the Richard chased two ships, which the daylight revealed to be the Pallas and the long-missing Alliance, which at last rejoined. The wind was blowing fresh from the southwest, and the two ships under easy canvas slowly rolled along toward Flamborough Head. Late in the morning the Richard discovered a large brigantine inshore and to windward. Jones immediately gave chase to her, when the brigantine changed her course and headed for Bridlington Bay, where she came to anchor.

Bridlington Bay lies just south of Flamborough Head, which is a bold promontory bearing a lighthouse and jutting far out into the North Sea. Vessels from the north bound for Hull or London generally pass close to the shore at that point, in order to make as little of a detour as possible. For this reason Jones had selected it as a particularly good cruising ground. Sheltered from observation from one side or the other, he waited for opportunities, naturally abundant, to pounce upon unsuspecting merchant ships. The Baltic fleet had not yet appeared off the coast, though it was about due. Unless warned of his presence, it would inevitably pass the bold headland and afford brilliant opportunity for attack. If his unruly consorts would only remain with him a little longer something might yet be effected. To go back now would be to confess to a partial failure, and Jones was determined to continue the cruise even alone, until he had demonstrated his fitness for higher things. Fate had his opportunity ready for him, and he made good use of it.

CHAPTER X

THE BATTLE WITH THE SERAPIS

About noon on the 23d of September, 1779, the lookouts on the Richard became aware of the sails of a large ship which suddenly shot into view around the headland. Before any action could be taken the first vessel was followed by a second, a third, and others to the number of six, all close hauled on the starboard tack, evidently intent upon weathering the point. The English flags fluttering from their gaff ends proclaimed a nationality, of which, indeed, there could be no doubt. The course of the Richard was instantly changed. Dispatching a boat under the command of Lieutenant Henry Lunt to capture the brigantine, Jones, in high anticipation, headed the Richard for the strangers, at the same time signaling the Alliance, the Pallas, and the Vengeance to form line ahead on his ship-that is, get into the wake of the Richard and follow in single file. The Alliance seems to have been ahead and to windward of the Richard, the Pallas to windward and abreast, and the Vengeance in the rear of the flagship.

It had not yet been developed whether the six ships, which, even as they gazed upon them, were followed by others until forty sail were counted, were vessels of war or a merchant fleet under convoy; but with characteristic audacity Jones determined to approach them sufficiently near to settle the question. He had expressed his intention of going in harm's way, and for that purpose had asked a swift ship. He could hardly have had a slower, more unwieldy, unmanageable vessel under him than the Richard, but the fact had not altered his intention in the slightest degree, so the course of the Richard was laid for the ships sighted.

Captain Landais, however, was not actuated by the same motives as his commander. He paid no attention, as usual, to the signal, but instead ran off to the Pallas, to whose commander he communicated in a measure some of his own indecision. In the hearing of the crews of both vessels Landais called out to his fellow captain that if the fleet in view were convoyed by a vessel of more than fifty guns they would have nothing to do but run away, well knowing that in such a case the Pallas, being the slowest sailer of the lot-slower even than the Richard-would inevitably be taken. Therefore, with his two other large vessels beating to and fro in a state of frightened uncertainty, Jones with the Richard bore down alone upon the enemy. The Vengeance remained far enough in the rear of the Richard to be safe out of harm's way, and may be dismissed from our further consideration, as she took no part whatever in the subsequent events.

Closer scrutiny had satisfied the American that the vessels in sight were the longed-for Baltic merchant fleet which was convoyed by two vessels of war, one of which appeared to be a small ship of the line or a heavy frigate. In spite, therefore, of the suspicious maneuvers of his consorts, Jones flung out a signal for a general chase, crossed his light yards and swept toward the enemy. Meanwhile all was consternation in the English fleet off the headland. A shore boat which had been noticed pulling hard toward the English convoying frigate now dashed alongside, and a man ascended to her deck. Immediately thereafter signals were broken out at the masthead of the frigate, attention being called to them by a gun fired to windward. All the ships but one responded by tacking or wearing in different directions in great apparent confusion, but all finally headed for the harbor of Scarborough, where, under the guns of the castle, they hoped to find a secure refuge. As they put about they let fly their topgallant sheets and fired guns to spread the alarm.

Meanwhile the English ship, which proved to be the frigate Serapis, also tacked and headed westward, taking a position between her convoy and the approaching ships. Some distance to leeward of the frigate, and farther out to sea, to the eastward, a smaller war vessel, in obedience to orders, also assumed a similar position, and both waited for the advancing foe. Early that morning Richard Pearson, the captain of the Serapis, had been informed that Paul Jones was off the coast, and he had been instructed to look out for him. The information had been at once communicated to the convoy, to which cautionary orders had been given, which had been in the main disregarded, as was the invariable custom with convoys. The shore boat which the men on the Richard had just observed speaking the Serapis contained the bailiff of Scarborough Castle, who confirmed the previous rumors and undoubtedly pointed out the approaching ships as Jones' squadron.

Pearson, as we have seen, had signaled his convoy, and the latter, now apprised of their danger beyond all reasonable doubt by the sight of the approaching ships, had at last obeyed his orders. Then he had cleverly placed his two ships between the oncoming American squadron to cover the retreat of his charges and to prevent the enemy from swooping down upon them. His position was not only proper and seamanlike, but it was in effect a bold challenge to his approaching antagonist-a challenge he had no wish to disregard, which he eagerly welcomed, in fact. In obedience to Jones' signal for a general chase, the Richard and the Pallas were headed for their two enemies. As they drew nearer the Pallas changed her course in accordance with Jones' directions, and headed for the smaller English ship, the Countess of Scarborough, a twenty-four gun, 6-pounder sloop of war, by no means an equal match for the Pallas. The Vengeance followed at a safe distance in the rear of the commodore, while Landais disregarded all signals and pursued an erratic course of his own devising. Sometimes it appeared that he was about to follow the Richard, sometimes the Pallas, sometimes the flying merchantmen attracted his attention. It was evident that the one thing he would not do would be to fight.

In utter disgust, Jones withdrew his attention from him and concentrated his mind upon the task before him. He was about to engage with his worn-out old hulk, filled with condemned guns, a splendid English frigate of the first class. A comparison of force is interesting. Counting the main battery of the Richard as composed of twelves and the spar-deck guns as nines, and including the six 18-pounders in the gun room as being all fought on one side, we get a total of forty guns throwing three hundred and three pounds of shot to the broadside; this is the extreme estimate. Counting one half of the main battery as 9-pounders, we get two hundred and eighty-two pounds to the broadside, and, considering the 18-pounders as being fought only three on a side, we reduce the weight of the broadside to two hundred and twenty-eight pounds. As it happened, as we shall see, the 18-pounders were abandoned after the first fire, so that the effective weight of broadside during the action amounted to either one hundred and ninety-five or one hundred and seventy-four pounds, depending on the composition of the main battery. Even the maximum amount is small enough by comparison.

The crew of the Richard had been reduced to about three hundred officers and men, as near as can be ascertained. The desertion of the barge, the loss of the boat under Cutting Lunt off the Irish coast, the various details by which the several prizes had been manned, and the absence of the boat sent that morning under the charge of Henry Lunt, which had not, and did not come back until after the action, had reduced the original number to these figures. A most serious feature of the situation was the lack of capable sea officers. There were so few of the latter on board the Richard originally that the absence of the two mentioned seriously hampered her work. Dale himself was a host. Those that remained, who, with the exception of the purser, sailing master, and the officers of the French contingent, were young and inexperienced, mostly midshipmen-boys, in fact-made up for their deficiencies by their zeal and courage. The officers of the French contingent proved themselves to be men of a high class, who could be depended upon in desperate emergencies.

The Serapis was a brand-new, double-banked frigate, of about eight hundred tons burden-that is, she carried guns on two covered and one uncovered decks. This was an unusual arrangement, not subsequently considered advantageous or desirable, but it certainly enabled her to present a formidable battery within a rather short length; her shortness, it was believed, would greatly enhance her handiness and mobility, qualities highly desirable in a war vessel, especially in the narrow seas. On the lower or main deck twenty 18-pounders were mounted; on the gun deck proper, twenty 9-pounders; and on the spar deck, ten 6-pounders, making a total of fifty guns, twenty-five in broadside, throwing three hundred pounds' weight of shot at each discharge as against the Richard's one hundred and seventy-four. She was manned by about three hundred trained and disciplined English seamen, forming a homogeneous, efficient crew, and well they proved their quality. Richard Pearson, her captain, was a brave, competent, and successful officer, who had enjoyed a distinguished career, winning his rank by gallant and daring enterprises; no ordinary man, indeed, but one from whom much was to be expected.

In making this comparison between the two ships it must not be forgotten that while the difference in the number of guns-ten-was not great, yet in their caliber and the consequent weight of broadside the Richard was completely outclassed. Then, too, the penetrative power of an 18-pound gun is vastly greater than that of a 12-pound gun, a thing well understood by naval men, though scarcely appearing of much moment on paper. Indeed, it was a maxim that a 12-pound frigate could not successfully engage an 18-pounder, or an 18-pound frigate cope with a 24-pound ship.12

In addition to this vast preponderance in actual fighting force, there was another great advantage to the Serapis in the original composition of her crew as compared with the heterogeneous crowd which Jones had been compelled to hammer into shape. Worthily, indeed, did both bodies of men demonstrate their courage and show the effect of their training. There was a further superiority in the English ship in that she was built for warlike purposes, and was not a converted and hastily adapted merchant vessel. She was of much heavier construction, with more massive frames, stouter sides, and heavier scantling. The last advantage Pearson's ship possessed was in her superior mobility and speed. She should have been able to choose and maintain her distance, so that with her longer and heavier guns she could batter the Richard to pieces at pleasure, herself being immune from the latter's feebler attack.

In but one consideration was the Richard superior to the Serapis, and that was in the personality of the man behind the men behind the guns! Pearson was a very gallant officer. There was no blemish upon his record, no question as to his capacity. In personal bravery he was not inferior to any one. As a seaman he worthily upheld the high reputation of the great navy to which he belonged; but as a man, as a personality, he was not to be mentioned in the same breath with Jones.

This is no discredit to that particular Englishman, for the same disadvantageous comparison to Jones would have to be made in the case of almost any other man that sailed the sea. There was about the little American such Homeric audacity, such cool-headed heroism, such unbreakable determination, such unshakable resolution, that so long as he lived it was impossible to conquer him. They might knock mast after mast out of the Richard; they might silence gun after gun in her batteries; man after man might be killed upon her decks; they might smash the ship to pieces and sink her beneath his feet, but there was no power on earth which could compel him to strike her flag.

Jones was the very incarnation of the indomitable Ego: a soul that laughed at odds, that despised opposition, that knew but one thing after the battle was joined-to strike and strike hard, until opposition was battered down or the soul of the striker had fled. In action he would be master-or dead. But his fighting was no baresark fury; no blind, wild rage of struggle; no ungovernable lust for battle; it was the apotheosis of cool-blooded calculation. He fought with his head as well as with his heart, and he knew perfectly well what he was about all the time. Pearson was highly trained matter of first-rate composition; Jones was mind, and his superiority over matter was inevitable. The hot-tempered spirit of the man which involved him in so many difficulties, which made him quarrelsome, contrary, and captious, gave place to a coolness and calmness as great as his courage in the presence of danger, in the moment of action. By his skill, his ability, his address, his persistence, his staying power, his hardihood, Jones deserved that victory which his determination absolutely wrested from overwhelming odds, disaster, and defeat. The chief players in the grim game, therefore, were but ill matched, and not all the superiority in the pawns upon the chessboard could overcome the fearful odds under which the unconscious Pearson labored. We pity Pearson; in Jones' hands he was as helpless as Pontius Pilate.