Полная версия:

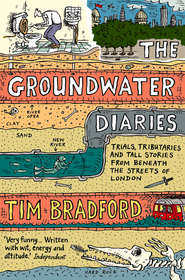

The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London

‘Get me some fucking leeks, you little bitch,’ shouts her mum.

‘I don’t want to,’ says the girl and the mother is looking very, very angry. Get the leeks, go on, for a quiet life.

‘I don’t know what leeks look like anyway,’ the girl shouts up, then runs away. A right turn and there’s an old wooden bench on a patch of grass that once would have had old lads sitting down looking over the view, now it just looks onto the health centre. Look, there’s the window where they had the wart clinic. Ah, those were the days. Across Green Lanes again into the back streets and onto Wilberforce Road, with its rows of massive Victorian houses where there are always big puddles on the tarmac. Only 150 years ago all this area north of here up to Seven Sisters Road was open countryside with two big pubs, the Eel Pie House and the Highbury Sluice alongside the river, where anglers and holidaymakers would hang out. Then, in the 1860s, the pubs were pulled down and everything built over in a mad frenzy. If you compare an 1850s map of the district and the 1871 census map you can see the rapid growth of residential streets in Highbury and south Finsbury Park.

On Blackstock Road there are a couple of charity shops and a huge Christian place, all with great second-hand (or more likely third-or fourth-hand) record sections. Their main trade, however, is in the suits of fat-arsed and tiny-bodied dead people and eighties computer games (i.e. Binatone football and tennis – which is just that white dot moving from a line one side of your screen to another). They also have a fine selection of crappy prints in plastic gilt frames – mostly rural scenes, Italian village harbours and matadors. I buy a lot of crappy pictures in gilt frames and paint my own crappy pictures of London scenes over them, most recently Finsbury Park crossroads on top of a Haywainy pastiche. It’s cheaper than buying canvases and you get the frame thrown in too.

Now on Mountgrove Road, the old accordion shop is empty, the estate agents have moved, the graphics company has closed up, the electrical shop has been turned into flats. This was originally a continuation of what is now Blackstock Road, called Gypsy Lane, but it’s been cut off, like an oxbow lake. Cross over my road and you’re suddenly into very different territory – there’s an invisible border I call The Scut Line with cafés and corner shops on one side, nice restaurants and flower shops on the other. It marks a boundary of the old parishes of Hornsey, St Mary’s and Stoke Newington. The mad drunken people of Finsbury Park and Highbury Vale don’t stray south of the line, marked by the Bank of Friendship pub (‘bank’ possibly alluding to a riverbank). People would stand on one side of the river here and shout at the poncey Stoke Newington wankers – ‘Oi, Daniel Defoe, your book is rubbish!’

The course of the New River has been altered several times in the last 400 years. Originally it flowed around Holloway towards Camden, but in the 1620s it was diverted east to Finsbury Park and Highbury. Since these early days most of the winding stretches were replaced by straighter sections and its capacity was increased to cope with the capital’s increased demand for water. This meant taking water from other streams, to the fury of people whose livelihood relied on the rivers, such as millers, fishermen and fat rich red-faced landowners who just liked complaining. Later on, pumping stations were put up along the route which pumped underground water to add to the river’s flow. Until recently the New River still supplied the capital with drinking water, 400 years after completion. It’s obsolete now that Thames Water’s new Ring Main system is operational.

The river now runs only as far as the reservoirs to the north of Stoke Newington. South of here it’s mostly been covered over – this happened in 1952 when the Metropolitan Board of Works, eager four-eyed bureaucrats with E. L. Whisty voices, made it their policy for health reasons.

Across Green Lanes yet another time, past the little sluice house and the White House pub where skinheads drink all afternoon, and into Clissold Park. Originally called Newington Park and owned by the Crawshay family it was renamed, along with the eighteenth-century house, after Augustus Clissold, a sexy Victorian vicar who married the heiress (all property in those days going to the person in the family with the fuzzy whiskers). The now ornamental New River appears and bends round in front of the house. It ends at a boundary stone between the parishes of Hornsey and Stoke Newington, marked ‘1700’, although it would originally have turned a right-angle here and flowed back west along the edge of the park. Where there used to be a little iron-railed bridge over the stream is the site of a café where the chips are fantastic and the industrial-strength bright-red ketchup makes your lips sting. This is the very edge of Stoke Newington (origin: ‘New Farm by the Tree Stumps’). The area, once a smart retreat for rich city types and intellectual nonconformists such as Daniel Defoe and Mary Shelley. went downhill badly after the war and by the seventies was regarded as an inner-city shit hole. Over the last ten years or so the urban pioneers (people with snazzy glasses, sharp haircuts and a liking for trendy food) have moved in and the place is on the up once more. I walk down the wide Petherton Road, which has a grassed island in the middle where the river used to run, towards Canonbury.

At Canonbury I enter a little narrow park where an ornamental death mask of the river runs for half a mile. This is a great idea in principle but in reality it’s faux-Zen Japaneseland precious, some sensitive designer’s idea of tranquillity, rather than reflecting the history of the area and its people. Completely covered in bright green algae, the river looks more like a thin strip of lawn. Here, too, the river marks a boundary, between the infamous Marquess estate on one side and Tony Blair Victorian villa land on the other.

Canonbury Park, further south, is a more typical London scene: silver-haired senior citizens in their tight-knit Special Brew Appreciation Societies sit and watch the world go by (and shout at it now and again in foghorn voices). More and more people walk around these days clutching a can of extra strong lager, as a handy filter for the pain of modern urban life. Out of the park and into Essex Road – a statue of Sir Hugh Myddelton stands at the junction of Essex Road and Upper Street on Islington Green.

The walk ends at Clerkenwell at the New River Head, once a large pond and now a garden next to the Metropolitan Water Board’s twenties offices. Above the main door is the seal of the New River Company showing a hand emerging from the clouds, causing it to rain upon early seventeenth-century London. I go into the building and take a photo, then ask the receptionist if there are any pamphlets or information about the New River. He shrugs, although apparently the seventeenth-century wood-panelled boardroom of the New River Company still exists somewhere in the building.

A few days later I mentioned the walk I’d done to my next-door neighbour. She was already beginning to sense that I was obsessive, as it’s all I ever talk about to her these days, and told me about a book that mentions the New River. A family friend had lent it to her years before. Would I like to have a look at it? Ha ha. Give me the book, old woman, I screamed, twitching, and nobody will get hurt. It’s a crumbling old volume on the history of Islington, printed in 1812. Inside is a pull-out map from the 1735 which shows not only the New River but also a ‘Boarded River’ not on any of my other maps. What is this? I re-read the chapter in Wonderful London on the lost rivers and searched the net. Up comes The Lost Rivers of London, by Nicholas Barton. A couple of days later I’m eagerly poring over its contents – a survey and histories of many of the lost rivers – including the map he’s included with the routes of various underground rivers. According to him, it’s not the New River flowing under my road, but something called Hackney Brook. This is confusing.

But then I remembered the can of strong lager in the old pump house. Could it have been a clue to the New River’s mystery, a key to a parallel world? Naturally, I decided that it was – mad pissed people can see the barriers that are hidden from the rest of us, that’s why they stick to the areas they know. Perhaps, if I got pissed on extra strong lager and wandered out into the street I too might see the invisible lines and obstacles opening up before me. I promptly went out and bought a selection of the strong lagers on sale in my local off-licence. Kestrel Super, Carlsberg Special Brew, Tennent’s Super and Skol Super Strength (they’d run out of Red Stripe SuperSlash).

‘Having a party, mate?’ asked the shopkeeper.

When John Lennon first took LSD he apparently did so while listening to a recording of passages from the Tibetan Book of the Dead translated by Timothy Leary, some of which ended up as lyrics in ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, the last track on Revolver. Looking for a more modern psychic map I decided to watch one of my daughter’s videos, The Adventures of Pingu.

Skol Super (‘A smooth tasting very strong lager’ – alc. 9.2% vol.) 7.30p.m.: Tastes salty, tar, roads, burnt treacle. The side of my head starts to pulsate almost straight away. After five or six sips I feel like I’ve had a few puffs of a high-quality spliff; I should stop now. But no, my need for scientific knowledge is too strong. Sounds are much louder. The radiator behind the settee suddenly comes on and I nearly jump out of my skin. I’m becoming superhumanly sensitive already. I feel that my powers are increasing. Like someone out of the X-Men – actually, that’s not a bad idea for a comic book series, a group of superheroes who are all pissheads.

Carlsberg Special Brew (‘Brewed since 1950, Carlsberg Special Brew is the original strong lager. By appointment to the Royal Danish Court’ – Blimey, must be hard work being a royal in Denmark – alc. 9.0% vol.) 9.30p.m.: Took ages to finish the first one. This has a dry-sweet taste and lighter colour with a damp forty-year-old carpet smell. Could possibly do with another couple of years to age properly. It sobers me up after the Skol. Pingu, on its fourth re-run, is getting a little bit boring. Fucking throbbing in my head. This feels like poison in my system.

Tennent’s Super (‘Very strong lager. Consumer Helpline 0345 112244. Calls charged at local rate’ – alc. 9.0% vol.) 10.20p.m.: Sweet, more like normal beer with a nice deep amber colour and a thick frothy head. A few swigs of this and I’m really starting to feel pissed. I can feel large areas of my brain closing down for the night. But which parts, that’s the question?

‘On a scale of 1–100, how much shite am I talking now?’ I ask my wife.

‘Well, it’s difficult to say. You regularly talk a lot of shite.’ (I look hurt.)

‘But, yeah, any more than normal?’

She doesn’t answer. A police car, siren blaring and lights flashing, zooms down our road. I quickly rush upstairs and search for a copy of The Golden Bough. I don’t have one – never have. I’m drunk. I phone the Tennent’s Super Consumer Helpline and leave a message about the dangers of living over groundwater.

Kestrel Super (‘Super strength lager – an award-winning lager of outstanding quality’ – alc. 9.02% vol.) 11.20p.m.: Smells of Belgian beer. Very complex taste, with strong malt notes, flowery like a real ale. I stroke my chin. I want to unbutton my itching head which feels like it’s covered in chicken wire yet strangely I feel very focused. I have also started talking to myself in hyperbabble while thinking I’m actually very nice looking. Actually.

I suddenly realize that we are in deep shit – the evil water spirits are everywhere. Maybe they’re nice, not evil. I think the house might be haunted. I’m doing lots of pissing and have bad gut rot. But I also feel clear headed. Then start to feel a bit sick. I go to the wardrobe, take out a coat hanger, break off the ‘curvy bit’ and snap it in half, bending each piece at right angles. I then get two old pen cases to use as handles and da daaa I have dowsing rods! First off, the sitting room. I wander around and the rods are going crazy – there’s water everywhere. Or is it because I’m a bit pissed or walking over the house’s water pipes? I spend the next hour wandering around our road and the nearby streets, charting the areas above water, and noting down my findings on bits of crumpled-up paper. According to my calculations the river (whichever one) misses our house by about 10 feet and comes up the adjacent road then crosses over and runs under the pavement for a while before going underneath the houses and coming out again at the used car lot next to the White House pub. Back at the other end of the road I check out the Scut Line. It’s the start of a very steep hill heading towards Highbury Village. People who are pissed cant wolk up it gravity take sover superbrew legs. I am startinf to git a hedache or is it my riverline-seeuin 3rd eye? Uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuhh.

At the end of the month the heavens opened yet again, but this time they didn’t stop. Waterfalls of rain, thunder and lightning, dark grey skies. The local streets once more began to turn into small lakes and streams. Down on Blackstock Road where, according to the old book the Boarded (New) River and Hackney Brook crossed, ponds formed in the road. Around the country people were flooded out of their homes. And the London rivers seemed to be rising too.

The problem with burying rivers is that we can’t see, and know, what they’re doing. In times of heavy rain it’s not that the rivers themselves will burst – they are encased in concrete – but that the small springs and streams that would originally have flowed into them can’t get into the concrete culvert that the river has become and simply follow the old course, spreading out over the river’s flood plain. Four million people in London live on the flood plains of the lost rivers. One night in early November, Church Street was completely flooded at exactly the point where the New River used to cross over and head south towards Canonbury. The next morning, after more rain, there were huge floods in Clissold Park just where the Hackney Brook would have skirted around the ponds. At the end of Grazebrook Road, pockets of people wandered around in wellies, staring with disbelief at the expanding pool. We’ve got so cocooned in our soft, warm modern urban world that we’ve forgotten that nature is just outside the door. Some day these nineteenth-century shelters of bricks and mortar won’t be able to protect us any more.

One morning the tall smart-blazered Jehovah’s Witness appeared again at my front door and begged me to take a copy of the Watchtower.

‘See all this weather. It’s the end times. Just like the Bible says. Read this leaflet. Promise me you’ll read it.’

Film idea: The Hugh Myddleton Story

Adventure. Big budget/People dying. There’s a race on to see who can come up with the best idea. Myddleton wins but others try to sabotage his project. Love interest: she gets pinched by opposition but he wins her back at end. He also foils Gunpowder Plot and saves King. Not entirely accurate historically. Maybe played by Matt Damon. Shakespeare in there too. And the Spanish Armada. Maybe the fleet can only set sail when they’ve all had enough to drink. Triumphant music at end and high fives as Myddleton blows up Spanish ships. English all played by Americans, Spanish all played by posh English.

London Stories 1: The Dogpeople

The Dogpeople, mostly fat people in their fifties, congregate on the eastern side of Clissold Park, a good distance from the lesbian footballers and just slightly away from the pigeons (who they view as a rival gang. The pigeons ignore the Dogpeople and are more concerned with annoying the ducks.) The Dogpeople shout loudly at each other in high-pitched voices about flea powders and Pedigree Chum, as well as more risqué cries of ‘Johnny, Johnny! Come! Come!!’ A vague smell of urine wafts from their general direction. Various little rat-like dogs scamper around wearing the same kind of stupid sleeveless quilted jackets as their owners. I try to kick them as they run past, but they are always too quick for me. The dogs, that is. The Dogpeople are easy targets. Their bottoms – invariably covered in green corduroy – are so large and soft they wouldn’t feel a thing.

On our street lives one of the Dogpeople ringleaders. Her dog is a pedigree, called something like Chormingly St John Carezza Jane Birkin O’Reilly. They’ve nicknamed him Petrocelli. Every night she puts a bowl out for Petrocelli in her back yard, and he laps heavily at it. It sounds like some bad overdubbing from a Seventies European ‘adult movie’. One great idea I had for Mrs Dogperson was that they could fill their dogs with helium and fly them like kites. They could then do loads of great aerobatic tricks – catch the stick, flying bottom sniffing. It then occurred to me that I’d have to find a solution to the problem of dog shit dropping out of the sky at regular intervals. Perhaps some sort of municipal London version of the American Star Wars defence system. My brother has worked with lasers. He might be able to sort that. Or attach buckets to the dogs. Or put helium into their food so that the shit flies upwards as well. And before you ask, I have a grade C physics O Level.

When the Dogperson was ill I offered to walk Petrocelli through the park in the mornings on my way to the childminder’s, thinking I might be able to ingratiate myself with the Dogpeople. It worked. Suddenly lots of earthy types in wellies started saying hello to me and pointing at the dog. So I had loads of new mates. The downside was the dog shit. I began to smell of it. Mrs Dogperson gave me polythene bags to scoop his poop, but the stupid dog kept shitting far too much and I’d get it all over my hands. Then when I tried to put it into the special dog-shit bins they had a spring-loaded door so I’d get my hand caught and the pooh would ooze out though the plastic onto my skin. I was also pushing a pram, so it was like driving a car using two different-sized rudders. Petrocelli would always try and force the pram in front of oncoming traffic so he could have me all to himself. Eventually I had to withdraw my offer of help and let Mrs Dogperson fend for herself. I wanted to be able to bite my nails without fear of disease.

The authorities are getting wise to the Dogpeople Problem. Already, police helicopters hover for ages at night over Stoke Newington and Finsbury Park. There are various theories about this (drugs, crime, drug crime), but my guess is that they must contain highly trained police marksmen, who are paid a hefty bounty to take out Dogpeople using airguns. Next time you see a lone mutt running down the street and you smile at the absence of a big-arsed minder waddling behind, remember that it’s the taxpayers – you and me – who pay for the bullets.

1 Wasn’t Algae Scum a character in Rupert Bear? A Borstal Boy piglet.

3. Football, the Masons and the Military-Industrial Complex

• Hackney Brook – Holloway to the River Lea

Arsenal – the football conspiracy – Beowulf – the weather – the Masons – Record Breakers – Holloway Road – Joe Meek – Freemasons – Arsenal – PeterJohnnyMick – Clissold Park – Abney Park cemetery – Salvation Army – Hackney – Hackney Downs – tower blocks – Hackney Wick – Occam’s shaving brush

Want to hear something amazing? If you look at a map of the rivers of London then place the major football stadiums over the top of it you’ll see that most of them are on, or next to, the routes of waterways. Does that make you come out all goosepimply like it did me? Well, here’s the hard facts that’ll send you rushing for the bog: Wembley – the Brent; Spurs – the Moselle; Chelsea – Counters Creek; Millwall – the Earl’s Sluice; Leyton Orient (sound of big barrel being scraped hard) – Dagenham Brook; Brentford – the Brent (too easy); Fulham – the Thames; Wimbledon – used to play near the banks of the Wandle; QPR – the exception that proves the rule; West Ham – OK, so that’s the end of my theory. But what of Arsenal?

I have a tatty old nineteenth-century Great Exhibition map1 on my wall at home on which the London of 150 years ago looks like a virulent bacteria on a petri dish. I have always liked saying 47 to friends, look, see where you live now? Well, look, it was once a … field. Then I’ll stand back with a self-satisfied expression while they shrug as if to say ‘Who gives a fuck, have you got any more wine?’ The Hackney Brook is marked on this map as a small stream near Wells Street in central Hackney. It also appears in various other sections, as a sewer along Gillespie Road, a small watercourse continuing off it towards Holloway and a river running from Stoke Newington to the start of Hackney, then stopping and continuing again around Hackney Wick towards the River Lea, before disappearing in a watery maze of cuts and artificial channels.2 But when I transferred the route of this little stream onto my A to Z it struck me that Highbury Stadium, Arsenal football ground, lay right on the course of the stream.

Arsenal are planning to move to another site at Ashburton Grove, half a mile away. This too lies above the Hackney Brook, at a point where two branches of it converge. What’s going on? Is there something about rivers that is good for football grounds? Water for the grass, perhaps? At one time they also wanted to move to an area behind St Pancras Station, the site of the Brill, a big pool near the River Fleet and, according to William Stukely, a pagan holy site.

And, while we’re at it, how did former manager Herbert Chapman manage to get the name of Gillespie Road tube changed to Arsenal in the thirties? Did he inform local council members that Dizzy Gillespie (who the street was named after) was, in fact, black and so all hell broke loose? How did Arsenal manage to get back into the top division after being relegated in 1913? Some sort of stitch up, no doubt. And how did they get hold of this prime land in North London? Did they channel the magical powers of the Hackney Brook using thirties superstar Cliff Bastin’s false teeth as dowsing rods?

A clue is in the club’s original name, from its origins in south London. The fact that it was called Woolwich Arsenal and was a works team is all the proof we need that the club is part, or at least was once a part, of the Military-Industrial Complex. They are the New World Order. Their colours – red shirts with white sleeves – are also simply a modern version of the tunics of the Knights Templar, forerunners of the Masons. Maybe their ground is situated near a stream because they need the presence of sacred spring water for their holy rituals. You know, pulling up their trousers and sticking the eye of a dead fish onto a slice of Dairylea cheese spread.

A search on the Internet for ‘Hackney Brook’ reveals only eleven matches, some of which are duplicates. One of the most interesting is a listings page of Masonic lodges in London. Lodge 7397 is the Hackney Brook Lodge, which meets in Clerkenwell on the fourth Monday of every fourth month. Why were they called Hackney Brook? Maybe they knew why the river had been buried. The Masons know all about all sorts of ‘hidden stuff’. Hidden stuff is why people join the Masons.

I love the idea of the lost rivers being somehow bound up in a mystical conspiracy. Maybe the rivers were pagan holy waters and the highly Christian Victorians wanted to bury the old beliefs for good and replace them with a new religion. Or what if developers – the Masons, the bloke with the big chin from the Barratt homes adverts (the one with the helicopter) – wanted new cheap land on which to build?

I have a dream about Highbury and Blackstock Road in the past, a semi-rural landscape of overlapping conduits and raised waterways, a Venice meets Spaghetti Junction. I am walking over deep crevasses covered by glass peppered with little red dots. Water flies through large glass tunnels, crisscrossing one way then another. Purple water froths over in a triumphal arch. It’s like some vaguely remembered scene from a sci-fi short story.