Полная версия:

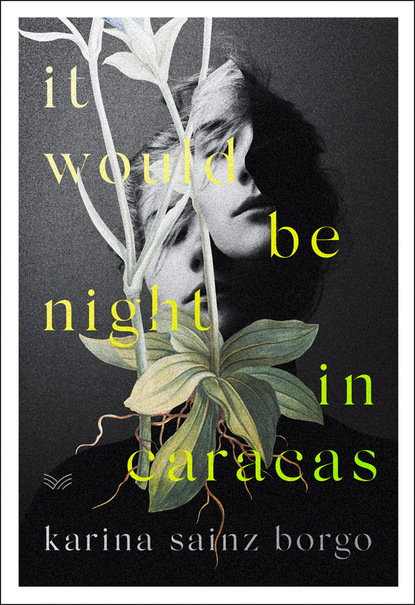

It Would Be Night in Caracas

I remember he was printed on the first page of El Nacional, the newspaper my mother read every morning at the table from the last page to the first. Not a day of her life went by that she didn’t buy it. At least while there was still reams of paper to print it on. If there was a newspaper, she would go down to the newsstand to buy it. That morning she brought it back, along with a pack of cigarettes, three ripe bananas, and a bottle of water—everything she could find at the grocery store, which shut its doors whenever rumors of a new band of looters started circulating.

She arrived home disheveled, puffing, the newspaper tucked under an arm. She dropped the paper on the table and ran to phone her sisters. While she tried to convince them that everything was fine, which wasn’t the case at all, I grabbed the newspaper and spread it out on the granite floor. The main photograph, which depicted the military repression and national carnage, covered the entire front page. And that was when he appeared before me. A young soldier lying in a pool of blood. I peered closer, examining his face. He seemed perfect, handsome. His head fallen and lolling on the road’s shoulder. Poor, slim, almost adolescent. His helmet was askew, which meant that his head, shattered by a bullet from a FAL rifle, was visible. There he was: split open like a fruit. A prince charming, his eyes flooded with blood. A few days later I got my first period. I was already a woman: beholden to a sleeping beauty who was killing me out of love and grief. My first boyfriend and my last childhood doll, covered in bits of his own brain, which one shot to the forehead had blown apart. Yes, at ten years old, I was a widow. At ten, I was already in love with ghosts.

I TOOK STOCK of our home library. On some of the books’ covers I could see the colored circles that for so many years, bored and with no parks to play in, I made while my mother imparted her lessons on “subjectverbpredicate.” Told not to leave my room, I equipped myself with an armful of books. Sometimes I read from their pages, at other times I only played with them. I unscrewed the lids of the tempera paint pots and pressed them against the bound pages at random: an orange ring for In Cold Blood to match the butane color of its cover; yellow, the color of little chicks, for The Autumn of the Patriarch to bring out the mustard of the design; burgundy in the case of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Almost every book bore a circular mark, as if I’d branded each before returning them to their shelves so they could graze quietly and at ease. Why didn’t those marks fade with the passing of time when all our transgressions remain? I wondered, The Green House in hand.

Next, I opened my mother’s wardrobe. I found her size 36 shoes. Arranged in pairs, now they had the air of a platoon of tired soldiers. I inspected the belts that once showed off her slim waist, and the dresses on their coat hangers. None of her things were garish or over the top. My mother was a fakir. A discrete woman who never cried and who, whenever she gave me a hug, created a paradise around me, a second womb scented with nicotine and moisturizer. Adelaida Falcón smoked and took care of her skin in equal measure. In the university residence hall for young ladies, where she spent five years of her life, she learned both to groom herself and to smoke. From then on, she never stopped reading, gently applying face cream to her cheeks, or quietly drawing on her cigarettes. Those were her happiest days, she often said. Every time she voiced those words, a question burned within me: Had the years she’d lived with me by her side put an end to the good times of her youth?

I rummaged around in the back of the wardrobe until I found the blouse of hers that was covered in monarch butterflies. Black and gold sequins were sewn all over it. I’d always loved it to bits. Whenever I removed it from the hanger and held it in my hands, the few square meters of the world my mother and I inhabited were suffused with wonder. The blouse was a swanky version of the glittery cocoons I dreamed about. Magical clothing, made of otherworldly color and fabric. I spread it out on the bed, asking myself why my mother bought it when she never slipped it on.

“How can I step out in that at eight in the morning?” she would say if I suggested she wear it to a PTA meeting. No matter how much I begged, she never went to a meeting wearing the blouse.

I studied at a school run by nuns, a stand-in for a more prestigious institution that wouldn’t take me because, at the interview, the principal learned that my mother wasn’t married and wasn’t a widow either. And although she never said anything to me about the incident, I came to understand it as symptomatic of the congenital disease that in those years afflicted the Venezuelan middle class: the defects of nineteenth-century white Venezuelans grafted onto the chaos of a mixed-race society. A country where women birthed and brought up children on their own, thanks to men who didn’t even bother pretending that they were stepping out for cigarettes when they decided to leave for good. Acknowledging this, of course, was part of the penance. The stumbling block on the steep ladder of social ascent.

I grew up surrounded by the daughters of immigrants. Girls with dark skin and light eyes. A summation, centuries in the making, of a strange and mestizo country’s practices in the bedroom. Beautiful in its derangements. Generous in beauty and in violence, two of the qualities that it had in greatest abundance. The result was a nation built on the cleft of its own contradictions, on the tectonic fault of a landscape always on the brink of tumbling down on its inhabitants’ heads.

Though less exclusive, my school likewise levied restraint on a society that was a long way from having it. In time, I understood that place as the breeding ground for a much greater evil, the natural resource of a cosmetic republic. Frivolity was the least egregious of its evils. Nobody wanted to grow old or appear poor. It was important to conceal, to make over. Those were the national pastimes: keeping up appearances. It didn’t matter if there was no money, or if the country was falling to pieces: the important thing was to be beautiful, to aspire to a crown, to be the queen of something … of Carnaval, of the town, of the country. To be the tallest, the prettiest, the most mindless. Even now, amid the misery that reigns in the city, I can still make out traces of that defect. Our monarchy was always like that: it belonged to the most dashing, to the handsome man or the great beauty. That’s what the whole thing that swelled into the cataclysm of vulgarity was about. Back then, we could get away with it. Our oil reserves paid the outstanding accounts. Or so we thought.

I WENT OUT. I needed sanitary napkins. I could live without sugar, coffee, and cooking oil but not without pads. They were even more valuable than toilet paper. I paid a premium to a group of women who controlled the few packets that made it to the supermarket. We called the women bachaqueras, and they acted with as much precision as the leafcutter ants they were named after. They went around in groups, were quick on their feet, and swarmed on everything that crossed their path. They were the first to arrive at the supermarkets and knew how to bypass the caps per person on regulated products. They got hold of what we couldn’t, so they could sell it to us at an inflated price. If I was prepared to pay three times the going rate, I could get whatever I wanted. And that’s what I was doing. I wrapped three wads of hundred-bolívar bills in a plastic bag. In exchange, I received a packet of twenty sanitary napkins. It cost me even to bleed.

I started to ration everything to avoid having to go out and find it. The only thing I needed was silence. I barely opened the windows. The revolutionary forces used tear gas to repress the people who were protesting the rationing decrees, and the fumes impregnated everything, making me vomit until I was pale. I sealed all the windows with duct tape, except the ones in the bathroom and kitchen, which didn’t face the street. I did all I could not to let anything make its way in from outside.

I answered only calls from the publishing house staff, who decided to give me a week’s grace period for my loss. I’d fallen behind with revising a few galley proofs. It was in my interest to invoice for the job, but I felt incapable of doing the work. I needed money but had no way of receiving it. There was no connection for carrying out transfers. The internet worked in fits and bursts. It was slow and patchy. All the bolívares I’d deposited in a savings account had been spent on my mother’s treatment. As for the pay I’d received for my editing work, there wasn’t much left, with an additional problem. By order of the Sons of the Revolution, foreign currency had become illegal. Having any amounted to treason.

When I turned on my phone three messages pinged, all from Ana. One to ask how I was, and two of the kind that get sent by default to a phone’s entire contact list. The message stated that fifteen days had gone by with no news from Santiago and asked us to sign a petition for his freedom. I didn’t respond. I couldn’t do anything for her, and she couldn’t do anything for me. We were condemned, like the rest of the country, to become strangers to ourselves. It was survivor’s guilt, and those who left the country suffered from it too, a mixture of reproach and shame: opting out of suffering was another form of betrayal.

Such was the power of the Sons of the Revolution. They separated us on two sides of a line. Those who have and those who have not. Those who leave and those who stay. Those who can be trusted and those who cannot. Apportioning blame was just one more division that they cleaved through a society already riddled with them. I wasn’t having an easy time of it, but if there was one thing I was sure of, it was that my circumstances could be worse. Being free of death’s stranglehold condemned me to silence out of decency.

IN THE MIDST of that night’s shoot-out, I realized my neighbor’s flush hadn’t sounded. I hadn’t seen Aurora Peralta since my mother went into palliative care. I was surprised to realize I hadn’t heard the irritating pull of the chain, which night after night sounded through my bedroom wall, interrupting my dreams with its gurgle of wastewater.

I knew very little about Aurora. Only that she was timid and dowdy, and that everyone called her “the Spanish woman’s daughter.” Her mother, Julia, was a Galician who ran a small eatery in La Candelaria, the area in Caracas with the largest concentration of bars run by Spanish immigrants. They were frequented by immigrants from Galicia and the Canary Islands, and by the odd Italian.

Almost all the customers were men. They went there to drink bottles of beer, which they sipped unenthusiastically. Even in the hellish heat, they pecked at chickpea-and-spinach stew, lentils with chorizo, or tripe and rice. Casa Peralta was known as the best place in the city to eat mussel-and-white-bean stew. Judging by the number of diners, that was a fair assessment.

Julia, the owner, had been one of the many Spanish women who made a living from the trades they plied before coming to Venezuela: cooking, dressmaking, farming, waitressing, nursing. Yet, most started out working as housekeepers for the local bourgeoisie in the fifties and sixties; others opened small stores and other businesses. They had only one thing to live by: their hands. Spanish printers, booksellers, and some teachers came to the city too and became part of our lives, bringing with them those resounding, lisped z’s that cut through the air in any conversation until they made our pronunciation their own.

Aurora Peralta, like her mother, made a living by cooking for others. For quite some time both before and after Julia’s death, she ran the family restaurant. Then she sold it to start up a pastry-making business that she ran from home. Renting premises was expensive, and it was risky: anyone could stage a holdup and take everything she had, not to mention shoot the unfortunate person who at that moment had access to the cash register.

Only nine years separated us, but she already seemed like an old lady. She came over a few times with a cake just out of the oven. Like her mother when she was alive, she seemed affable and generous. And one thing in her life resembled my own: she had no father. Or at least that was the conclusion I came to when I noticed that the life she and her mother led looked a lot like ours. They started and ended each day together, as mother and daughter. I’d been surprised when she hadn’t come to my mother’s wake. I’d told her in person how poorly my mother was when she’d asked after her health. I assumed the shortages of flour, eggs, and sugar had put a strain on her business, that she was going through a tough time, or had returned to Spain, if she still had family there. Then I forgot about her as easily as I forgot about a faulty lightbulb. I was too busy completing a second gestation, nourished only by my mother, whose presence I could still feel around me. I didn’t need or want anything else. No one would take care of me, and I wouldn’t take care of anyone. If things got worse, I would earn my right to live by walking all over the rights of others. It was them or me. There was no one alive in that country who was generous enough to give me a coup de grâce. No one would blindfold me or put a cigarette in my mouth. No one would pity me when my time came.

MY MOTHER’S BELONGINGS were, finally, in boxes to one side of the home library. They looked like baggage that time had packed behind our backs. I resisted the urge to give away or donate all of it. I didn’t intend to leave a single page, length of fabric, or splinter of wood to this doomed country going up in flames.

The days accumulated like the dead in the headlines. The Sons of the Revolution tightened the screws. They gave us reason to go out in the street, and all the while the state-sponsored bodies and armed cells repressed those who did, acting in groups with their faces covered, cleansing the pavements. No one was completely safe in their homes. Outside, in the jungle, methods to neutralize opponents reached an unprecedented degree of finesse. Across the nation the only thing in working order was the killing and stealing machine, the pillaging apparatus. I watched them grow and become part of the cityscape, just another feature of everyday life: a presence camouflaged in the disorder and chaos, protected and nourished by the Revolution.

Almost all the militias were made up of civilians. They acted under police protection. They started congregating by the trash heap at Plaza del Comandante, which we were still calling by its original name: Plaza Miranda, a tribute to the only truly liberal figure of our War of Independence, who died, like other good and just men, far from the country he’d given his all. That was where the Sons of the Revolution chose to establish their new command. Sons? I thought. And why not bastards? “Bastards of the Revolution,” I murmured on seeing a troupe of obese women, all dressed in red. They looked like a family. A gynoecium of roly-poly nymphs: fathers and brothers who were really mothers and sisters. Vestals armed with buckets of water and sticks, femininity in all its splendor and at its most bizarre.

The first day, a convoy of ten soldiers—faceless thanks to dark helmets with skull smiles—camped next to them. After a few weeks, more arrived. All the while more members of the Fatherland’s Motorized Fleet turned up. It was impossible to identify them. They wore the masks used by riot police. The lower half of the face was covered with the smiling jawbone of a skeleton and, at the height of the eyes, a piece of rubber was bored with holes. Why did they take such pains to hide their identity when the law was in their hands?

In contrast, the women showed their faces, baring their teeth like menacing dogs. They fought more fiercely. They landed punches. Once they’d managed to bring down an opponent, they dragged him along the ground and stripped him of everything. Everyone carried out their labors with immense gusto, though I never managed to understand what salary could be so high that their fury never abated. What did they get in exchange for the full-time job of smashing heads in as if they were melons? Our days were numbered.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов