Полная версия

Полная версияExpositor's Bible: The Book of Jeremiah, Chapters XXI.-LII.

On this occasion there was no rival prophet to beard Jeremiah and relieve his hearers from their fears and scruples. Probably indeed no professed prophet of Jehovah would have cared to defend the worship of other gods. But, as at Bethlehem, the people themselves ventured to defy their aged mentor. They seem to have been provoked to such hardihood by a stimulus which often prompts timorous men to bold words. Their wives were specially devoted to the superstitious burning of incense, and these women were present in large numbers. Probably, like Lady Macbeth, they had already in private

"Poured their spirits in their husbands' ears,And chastised, with the valour of their tongues,All that impeded"those husbands from speaking their minds to Jeremiah. In their presence, the men dared not shirk an obvious duty, for fear of more domestic chastisement. The prophet's reproaches would be less intolerable than such inflictions. Moreover the fair devotees did not hesitate to mingle their own shrill voices in the wordy strife.

These idolatrous Jews – male and female – carried things with a very high hand indeed: —

"We will not obey thee in that which thou hast spoken unto us in the name of Jehovah. We are determined to perform all the vows we have made to burn incense and other libations to the Queen of Heaven, exactly as we have said and as we and our fathers and kings and princes did in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem."173

Moreover they were quite prepared to meet Jeremiah on his own ground and argue with him according to his own principles and methods. He had appealed to the ruin of Judah as a proof of Jehovah's condemnation of their idolatry and of His power to punish: they argued that these misfortunes were a divine spretæ injuria formæ, the vengeance of the Queen of Heaven, whose worship they had neglected. When they duly honoured her, —

"Then had we plenty of victuals, and were prosperous and saw no evil; but since we left off burning incense and offering libations to the Queen of Heaven, we have been in want of everything, and have been consumed by the sword and the famine."

Moreover the women had a special plea of their own: —

"When we burned incense and offered libations to the Queen of Heaven, did we not make cakes to symbolise her and offer libations to her with our husbands' permission?"

A wife's vows were not valid without her husband's sanction, and the women avail themselves of this principle to shift the responsibility for their superstition on the men's shoulders. Possibly too the unfortunate Benedicts were not displaying sufficient zeal in the good cause, and these words were intended to goad them into greater energy. Doubtless they cannot be entirely exonerated of blame for tolerating their wives' sins, probably they were guilty of participation as well as connivance. Nothing however but the utmost determination and moral courage would have curbed the exuberant religiosity of these devout ladies. The prompt suggestion that, if they have done wrong, their husbands are to blame for letting them have their own way, is an instance of the meanness which results from the worship of "other gods."

But these defiant speeches raise a more important question. There is an essential difference between regarding a national catastrophe as a divine judgment and the crude superstition to which an eclipse expresses the resentment of an angry god. But both involve the same practical uncertainty. The sufferers or the spectators ask what god wrought these marvels and what sins they are intended to punish, and to these questions neither catastrophe nor eclipse gives any certain answer.

Doubtless the altars of the Queen of Heaven had been destroyed by Josiah in his crusade against heathen cults; but her outraged majesty had been speedily avenged by the defeat and death of the iconoclast, and since then the history of Judah had been one long series of disasters. Jeremiah declared that these were the just retribution inflicted by Jehovah because Judah had been disloyal to Him; in the reign of Manasseh their sin had reached its climax: —

"I will cause them to be tossed to and fro among all the nations of the earth, because of Manasseh ben Hezekiah, king of Judah, for that which he did in Jerusalem."174

His audience were equally positive that the national ruin was the vengeance of the Queen of Heaven. Josiah had destroyed her altars, and now the worshippers of Istar had retaliated by razing the Temple to the ground. A Jew, with the vague impression that Istar was as real as Jehovah, might find it difficult to decide between these conflicting theories.

To us, as to Jeremiah, it seems sheer nonsense to speak of the vengeance of the Queen of Heaven, not because of what we deduce from the circumstances of the fall of Jerusalem, but because we do not believe in any such deity. But the fallacy is repeated when, in somewhat similar fashion, Protestants find proof of the superiority of their faith in the contrast between England and Catholic Spain, while Romanists draw the opposite conclusion from a comparison of Holland and Belgium. In all such cases the assured truth of the disputant's doctrine, which is set forth as the result of his argument, is in reality the premise upon which his reasoning rests. Faith is not deduced from, but dictates an interpretation of history. In an individual the material penalties of sin may arouse a sleeping conscience, but they cannot create a moral sense: apart from a moral sense the discipline of rewards and punishments would be futile: —

"Were no inner eye in us to tell,Instructed by no inner sense,The light of heaven from the dark of hell,That light would want its evidence."Jeremiah, therefore, is quite consistent in refraining from argument and replying to his opponents by reiterating his former statements that sin against Jehovah had ruined Judah and would yet ruin the exiles. He spoke on the authority of the "inner sense," itself instructed by Revelation. But, after the manner of the prophets, he gave them a sign – Pharaoh Hophra should be delivered into the hand of his enemies as Zedekiah had been. Such an event would indeed be an unmistakable sign of imminent calamity to the fugitives who had sought the protection of the Egyptian king against Nebuchadnezzar.175

We have reserved for separate treatment the questions suggested by the references to the Queen of Heaven.176 This divine name only occurs again in the Old Testament in vii. 18, and we are startled, at first sight, to discover that a cult about which all other historians and prophets have been entirely silent is described in these passages as an ancient and national worship. It is even possible that the "great assembly" was a festival in her honour. We have again to remind ourselves that the Old Testament is an account of the progress of Revelation and not a History of Israel. Probably the true explanation is that given by Kuenen. The prophets do not, as a rule, speak of the details of false worship; they use the generic "Baal" and the collective "other gods." Even in this chapter Jeremiah begins by speaking of "other gods," and only uses the term "Queen of Heaven" when he quotes the reply made to him by the Jews. Similarly when Ezekiel goes into detail concerning idolatry177 he mentions cults and ritual178 which do not occur elsewhere in the Old Testament. The prophets were little inclined to discriminate between different forms of idolatry, just as the average churchman is quite indifferent to the distinctions of the various Nonconformist bodies, which are to him simply "dissenters." One might read many volumes of Anglican sermons and even some English Church History without meeting with the term Unitarian.

It is easy to find modern parallels – Christian and heathen – to the name of this goddess. The Virgin Mary is honoured with the title Regina Cœli, and at Mukden, the Sacred City of China, there is a temple to the Queen of Heaven. But it is not easy to identify the ancient deity who bore this name. The Jews are accused elsewhere of worshipping "the sun and the moon and all the host of heaven," and one or other of these heavenly bodies – mostly either the moon or the planet Venus – has been supposed to have been the Queen of Heaven.

Neither do the symbolic cakes help us. Such emblems are found in the ritual of many ancient cults: at Athens cakes called σελῆναι, and shaped like a full-moon were offered to the moon-goddess Artemis; a similar usage seems to have prevailed in the worship of the Arabian goddess Al-Uzza, whose star was Venus, and also of connection with the worship of the sun.179

Moreover we do not find the title "Queen of Heaven" as an ordinary and well-established name of any neighbouring divinity. "Queen" is a natural title for any goddess, and was actually given to many ancient deities. Schrader180 finds our goddess in the Atar-samain (Athar-Astarte) who is mentioned in the Assyrian ascriptions as worshipped by a North Arabian tribe of Kedarenes. Possibly too the Assyrian Istar is called Queen of Heaven.181

Istar, however, is connected with the moon as well as with the planet Venus.182 For the present therefore we must be content to leave the matter an open question,183 but any day some new discovery may solve the problem. Meanwhile it is interesting to notice how little religious ideas and practices are affected by differences in profession. St. Isaac the Great, of Antioch, who died about a. d. 460, tells us that the Christian ladies of Syria – whom he speaks of very ungallantly as "fools" – used to worship the planet Venus from the roofs of their houses, in the hope that she would bestow upon them some portion of her own brightness and beauty. His experience naturally led St. Isaac to interpret the Queen of Heaven as the luminary which his countrywomen venerated.184

The episode of the "great assembly" closes the history of Jeremiah's life. We leave him (as we so often met with him before) hurling ineffective denunciations at a recalcitrant audience. Vagrant fancy, holding this to be a lame and impotent conclusion, has woven romantic stories to continue and complete the narrative. There are traditions that he was stoned to death at Tahpanhes, and that his bones were removed to Alexandria by Alexander the Great; that he and Baruch returned to Judea or went to Babylon and died in peace; that he returned to Jerusalem and lived there three hundred years, – and other such legends. As has been said concerning the Apocryphal Gospels, these narratives serve as a foil to the history they are meant to supplement: they remind us of the sequels of great novels written by inferior pens, or of attempts made by clumsy mechanics to convert a bust by some inspired sculptor into a full-length statue.

For this story of Jeremiah's life is not a torso. Sacred biography constantly disappoints our curiosity as to the last days of holy men. We are scarcely ever told how prophets and apostles died. It is curious too that the great exceptions – Elijah in his chariot of fire and Elisha dying quietly in his bed – occur before the period of written prophecy. The deaths of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, Peter, Paul, and John, are passed over in the Sacred Record, and when we seek to follow them beyond its pages, we are taught afresh the unique wisdom of inspiration. If we may understand Deuteronomy xxxiv. to imply that no eye was permitted to behold Moses in the hour of death, we have in this incident a type of the reticence of Scripture on such matters. Moreover a moment's reflection reminds us that the inspired method is in accordance with the better instincts of our nature. A death in opening manhood, or the death of a soldier in battle or of a martyr at the stake, rivets our attention; but when men die in a good old age, we dwell less on their declining years than on the achievements of their prime. We all remember the martyrdoms of Huss and Latimer, but how many of those in whose mouths Calvin and Luther are familiar as household words know how those great Reformers died?

There comes a time when we may apply to the aged saint the words of Browning's Death in the Desert: —

"So is myself withdrawn into my depths,The soul retreated from the perished brainWhence it was wont to feel and use the worldThrough these dull members, done with long ago."And the poet's comparison of this soul to

"A stick once fire from end to end;Now, ashes save the tip that holds a spark."Love craves to watch to the last, because the spark may

"Run back, spread itselfA little where the fire was…And we would not loseThe last of what might happen on his face."Such privileges may be granted to a few chosen disciples, probably they were in this case granted to Baruch; but they are mostly withheld from the world, lest blind irreverence should see in the aged saint nothing but

"Second childishness, and mere oblivion;Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything."BOOK II

PROPHECIES CONCERNING FOREIGN NATIONS

CHAPTER XVI

JEHOVAH AND THE NATIONS

xxv. 15-38"Jehovah hath a controversy with the nations." – Jer. xxv. 31As the son of a king only learns very gradually that his father's authority and activity extend beyond the family and the household, so Israel in its childhood thought of Jehovah as exclusively concerned with itself.

Such ideas as omnipotence and universal Providence did not exist; therefore they could not be denied; and the limitations of the national faith were not essentially inconsistent with later Revelation. But when we reach the period of recorded prophecy we find that, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, the prophets had begun to recognise Jehovah's dominion over surrounding peoples. There was, as yet, no deliberate and formal doctrine of omnipotence, but, as Israel became involved in the fortunes first of one foreign power and then of another, the prophets asserted that the doings of these heathen states were overruled by the God of Israel. The idea of Jehovah's Lordship of the Nations enlarged with the extension of international relations, as our conception of the God of Nature has expanded with the successive discoveries of science. Hence, for the most part, the prophets devote special attention to the concerns of Gentile peoples. Hosea, Micah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi are partial exceptions. Some of the minor prophets have for their main subject the doom of a heathen empire. Jonah and Nahum deal with Nineveh, Habbakuk with Chaldea, and Edom is specially honoured by being almost the sole object of the denunciations of Obadiah. Daniel also deals with the fate of the kingdoms of the world, but in the Apocalyptic fashion of the Pseudepigrapha. Jewish criticism rightly declined to recognise this book as prophetic, and relegated it to the latest collection of canonical scriptures.

Each of the other prophetical books contains a longer or shorter series of utterances concerning the neighbours of Israel, its friends and foes, its enemies and allies. The fashion was apparently set by Amos, who shows God's judgment upon Damascus, the Philistines, Tyre, Edom, Ammon, and Moab. This list suggests the range of the prophet's religious interest in the Gentiles. Assyria and Egypt were, for the present, beyond the sphere of Revelation, just as China and India were to the average Protestant of the seventeenth century. When we come to the Book of Isaiah, the horizon widens in every direction. Jehovah is concerned with Egypt and Ethiopia, Assyria and Babylon.185 In very short books like Joel and Zephaniah we could not expect exhaustive treatment of this subject. Yet even these prophets deal with the fortunes of the Gentiles: Joel, variously held one of the latest or one of the earliest of the canonical books, pronounces a divine judgment on Tyre and Sidon and the Philistines, on Egypt and Edom; and Zephaniah, an elder contemporary of Jeremiah, devotes sections to the Philistines, Moab and Ammon, Ethiopia and Assyria.

The fall of Nineveh revolutionised the international system of the East. The judgment on Asshur was accomplished, and her name disappears from these catalogues of doom. In other particulars Jeremiah, as well as Ezekiel, follows closely in the footsteps of his predecessors. He deals, like them, with the group of Syrian and Palestinian states – Philistines, Moab, Ammon, Edom, and Damascus.186 He dwells with repeated emphasis on Egypt, and Arabia is represented by Kedar and Hazor. In one section the prophet travels into what must have seemed to his contemporaries the very far East, as far as Elam. On the other hand, he is comparatively silent about Tyre, in which Joel, Amos, the Book of Isaiah,187 and above all Ezekiel display a lively interest. Nebuchadnezzar's campaigns were directed against Tyre as much as against Jerusalem; and Ezekiel, living in Chaldea, would have attention forcibly directed to the Phœnician capital, at a time when Jeremiah was absorbed in the fortunes of Zion.

But in the passage which we have chosen as the subject for this introduction to the prophecies of the nations, Jeremiah takes a somewhat wider range: —

"Thus saith unto me Jehovah, the God of Israel:Take at My hand this cup of the wine of fury,And make all the nations, to whom I send thee, drink it.They shall drink, and reel to and fro, and be mad,Because of the sword that I will send among them."First and foremost of these nations, pre-eminent in punishment as in privilege, stand "Jerusalem and the cities of Judah, with its kings and princes."

This bad eminence is a necessary application of the principle laid down by Amos188: —

"You only have I known of all the families of the earth:Therefore I will visit upon you all your iniquities."But as Jeremiah says later on, addressing the Gentile nations, —

"I begin to work evil at the city which is called by My name.Should ye go scot-free? Ye shall not go scot-free."And the prophet puts the cup of God's fury to their lips also, and amongst them, Egypt, the bête noir of Hebrew seers, is most conspicuously marked out for destruction: "Pharaoh king of Egypt, and his servants and princes and all his people, and all the mixed population of Egypt."189 Then follows, in epic fashion, a catalogue of "all the nations" as Jeremiah knew them: "All the kings of the land of Uz, all the kings of the land of the Philistines; Ashkelon, Gaza, Ekron, and the remnant of Ashdod;190 Edom, Moab, and the Ammonites; all the kings191 of Tyre, all the kings of Zidon, and the kings of their colonies192 beyond the sea; Dedan and Tema and Buz, and all that have the corners of their hair polled;193 and all the kings of Arabia, and all the kings of the mixed populations that dwell in the desert; all the kings of Zimri, all the kings of Elam, and all the kings of the Medes." Jeremiah's definite geographical information is apparently exhausted, but he adds by way of summary and conclusion: "And all the kings of the north, far and near, one after the other; and all the kingdoms of the world, which are on the face of the earth."

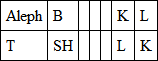

There is one notable omission in the list. Nebuchadnezzar, the servant of Jehovah,194 was the divinely appointed scourge of Judah and its neighbours and allies. Elsewhere195 the nations are exhorted to submit to him, and here apparently Chaldea is exempted from the general doom, just as Ezekiel passes no formal sentence on Babylon. It is true that "all the kingdoms of the earth" would naturally include Babylon, possibly were even intended to do so. But the Jews were not long content with so veiled a reference to their conquerors and oppressors. Some patriotic scribe added the explanatory note, "And the king of Sheshach (i. e. Babylon) shall drink after them."196 Sheshach is obtained from Babel by the cypher 'Athbash, according to which an alphabet is written out and a reversed alphabet written out underneath it, and the letters of the lower row used for those of the upper and vice versâ. Thus

The use of cypher seems to indicate that the note was added in Chaldea during the Exile, when it was not safe to circulate documents which openly denounced Babylon. Jeremiah's enumeration of the peoples and rulers of his world is naturally more detailed and more exhaustive than the list of the nations against which he prophesied. It includes the Phœnician states, details the Philistine cities, associates with Elam the neighbouring nations of Zimri and the Medes, and substitutes for Kedar and Hazor Arabia and a number of semi-Arab states, Uz, Dedan, Tema, and Buz.197 Thus Jeremiah's world is the district constantly shown in Scripture atlases in a map comprising the scenes of Old Testament history, Egypt, Arabia, and Western Asia, south of a line from the north-east corner of the Mediterranean to the southern end of the Caspian Sea, and west of a line from the latter point to the northern end of the Persian Gulf. How much of history has been crowded into this narrow area! Here science, art, and literature won those primitive triumphs which no subsequent achievements could surpass or even equal. Here, perhaps for the first time, men tasted the Dead Sea apples of civilisation, and learnt how little accumulated wealth and national splendour can do for the welfare of the masses. Here was Eden, where God walked in the cool of the day to commune with man; and here also were many Mount Moriahs, where man gave his firstborn for his transgression, the fruit of his body for the sin of his soul, and no angel voice stayed his hand.

And now glance at any modern map and see for how little Jeremiah's world counts among the great Powers of the nineteenth century. Egypt indeed is a bone of contention between European states, but how often does a daily paper remind its readers of the existence of Syria or Mesopotamia? We may apply to this ancient world the title that Byron gave to Rome, "Lone mother of dead empires," and call it: —

"The desert, where we steer

Stumbling o'er recollections."

It is said that Scipio's exultation over the fall of Carthage was marred by forebodings that Time had a like destiny in store for Rome. Where Cromwell might have quoted a text from the Bible, the Roman soldier applied to his native city the Homeric lines: —

"Troy shall sink in fire,

And Priam's city with himself expire."

The epitaphs of ancient civilisations are no mere matters of archæology; like the inscriptions on common graves, they carry a Memento mori for their successors.

But to return from epitaphs to prophecy: in the list which we have just given, the kings of many of the nations are required to drink the cup of wrath, and the section concludes with a universal judgment upon the princes and rulers of this ancient world under the familiar figure of shepherds, supplemented here by another, that of the "principal of the flock," or, as we should say, "bell-wethers." Jehovah would break out upon them to rend and scatter like a lion from his covert. Therefore: —

"Howl, ye shepherds, and cry!Roll yourselves in the dust, ye bell-wethers!The time has fully come for you to be slaughtered.I will cast you down with a crash, like a vase of porcelain.198Ruin hath overtaken the refuge of the shepherds,And the way of escape of the bell-wethers."Thus Jeremiah announces the coming ruin of an ancient world, with all its states and sovereigns, and we have seen that the prediction has been amply fulfilled. We can only notice two other points with regard to this section.

First, then, we have no right to accuse the prophet of speaking from a narrow national standpoint. His words are not the expression of the Jewish adversus omnes alios hostile odium;199 if they were, we should not hear so much of Judah's sin and Judah's punishment. He applied to heathen states as he did to his own the divine standard of national righteousness, and they too were found wanting. All history confirms Jeremiah's judgment. This brings us to our second point. Christian thinkers have been engrossed in the evidential aspect of these national catastrophes. They served to fulfil prophecy, and therefore the squalor of Egypt and the ruins of Assyria to-day have seemed to make our way of salvation more safe and certain. But God did not merely sacrifice these holocausts of men and nations to the perennial craving of feeble faith for signs. Their fate must of necessity illustrate His justice and wisdom and love. Jeremiah tells us plainly that Judah and its neighbours had filled up the measure of their iniquity before they were called upon to drink the cup of wrath; national sin justifies God's judgments. Yet these very facts of the moral failure and decadence of human societies perplex and startle us. Individuals grow old and feeble and die, but saints and heroes do not become slaves of vice and sin in their last days. The glory of their prime is not buried in a dishonoured grave. Nay rather, when all else fails, the beauty of holiness grows more pure and radiant. But of what nation could we say: —