Полная версия:

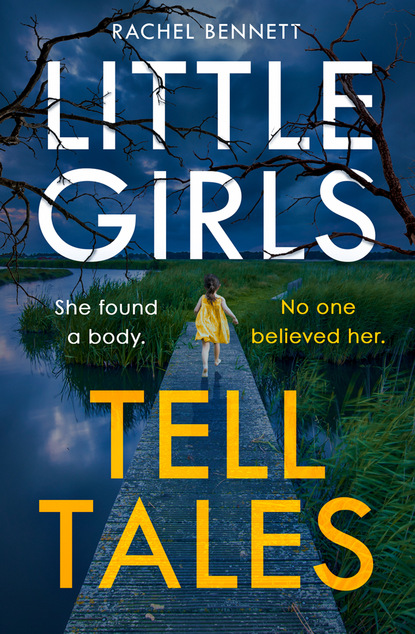

Little Girls Tell Tales

Out in the hall and up the stairs. Here were more reminders of Beth, her face smiling from almost every framed picture on the wall. But there were also reminders of Mum. The wallpaper was her favourite shade of green. There were ring marks on the pale wood of the lowermost three stairs, where she’d rested her cup of tea while she’d chatted on the phone to my aunt for hours. After Mum moved out, we could’ve changed the wallpaper or sanded the stairs, but again Beth had talked me round. ‘It’s charming,’ she’d said. ‘Gives the place character.’

After I’d opened the curtains in the two upstairs bedrooms, I went into the study and sat down. There were no blinds in here because the dormer window was such an awkward shape, and the sun hit the room squarely at this time of day, gradually warming the dusty air. I rolled the chair into the rectangle of sunlight and closed my eyes.

The house was too big for me on my own. Together, me and Beth had filled the rooms, but now I was too aware of the echoing hardwood floors and high, cavernous ceilings. It’d turned out Beth was right – we could’ve used more clutter. It might’ve disguised the hard edges of the house that I’d never noticed.

But I knew I could never move. For a start, there was no way I could afford anywhere half as nice. The house was still in Mum’s name, but after I was signed off work, she quietly stopped asking me for rent. My benefit payments covered the utilities and my daily expenses. I knew exactly how lucky I was. Not everyone in my position could live somewhere so lovely.

Lucky. My mouth twisted. Lucky me, to be living in a beautiful house in a beautiful location, where every little thing reminded me of what I’d lost.

I’d taken a week off before and after the funeral. Then my doctor had signed me off for another week. My employers had been understanding; how could they not? They’d told me to take as much time as I needed. Maybe they would’ve thought twice if they’d known how long I genuinely needed to recover. Like maybe forever. Eighteen months later and here I was. Still not whole.

In fact, if it wasn’t for Mum I’d probably never leave the house. It was a ten-minute journey into Ramsey, where Mum lived in her conveniently pokey flat. I made the drive once a week, every Sunday afternoon, combining it with a visit to the supermarket. I stuck to the routine for the same reasons I made myself draw the curtains each morning. Because it was too easy to sink. I had to keeping kicking my legs, at least a little, if I wanted to stay above water.

It frightened me how simple it was to give up. Although my employers had told me they’d keep my job open, in case I ever came back, I’d long ago accepted I wouldn’t return. I’d felt nothing but relief when I’d finally admitted it.

Since then, the house had become a sanctuary, despite the constant, unavoidable reminders of Beth wherever I looked. It was the one thing that rooted me to the world. I tidied, I sorted, I tended the garden. The garden in particular never failed to calm me. Here, the influence of my mother was strongest. Mum had planted these flowers, tended these beds, pruned these saplings. I would smile at the smallest things, such as the chicken-wire still wrapped loosely around the trunks of the fruit trees to guard against marauding wallabies.

‘A garden’s a promise you make to yourself,’ Mum would say. ‘You’re promising you want to be here to see it grow.’

It made me sad Mum couldn’t visit more often to see the garden growing. Every couple of months, I would take her for an outing, driving her back to the house so she could visit the garden and the curraghs. Those trips had been more frequent before Beth died, of course. Everything had declined since then.

I got out of the chair in the study and went back downstairs. Time for another cup of tea before I got dressed. I checked the doormat automatically and breathed a silent sigh of relief to see there was no post that morning.

After that I changed the bedsheets, hoovered the bedrooms, and put the bedding in to wash. That took me until lunchtime. After lunch, when the washing machine had finished, I hung out the sheets, in time to catch the sun at its warmest. Then I worked quietly in the garden. I spent a considerable amount of time tying up the honeysuckle at the side of the house, which had exploded into a million trailing shoots, each determined to burrow its way into the gutters or drainpipes. I loved the honeysuckle, but between it and the clematis at the opposite side of the house, I was fighting a constant battle for control.

Maybe that was the attraction of the garden. Mum had been smart to encourage me to spend as much time as possible with my hands in the dirt. As if she’d known I’d someday need this to occupy my mind and my hands.

I’d just come inside to make my fifth cup of herbal tea when the doorbell rang.

I washed my hands quickly and wiped them on my jogging pants as I went to the door. It was half past four on a Thursday afternoon. I wasn’t expecting any callers. But answering the door was an accepted part of life. I didn’t want to become the sort of person who hid from the outside world.

As I approached the door, I saw a letter lying on the mat, and my stomach dropped like a lead weight. I recognised the plain Manila envelope with the sloped handwriting on the front. It must’ve come while I was in the garden, unless … unless it’d been delivered right now, by the person outside.

Through the frosted glass of the upper half of my front door, I could see the fuzzed outline of my visitor. They rang the bell again, then cupped their hands to peer through the glass. I was sure they saw my shadow.

‘Rosie?’ the person called. ‘Rosie, you there?’

The voice was muffled, but I recognised it.

I snatched up the envelope from the mat and dropped it facedown onto the phone table before opening the door.

‘Rosie,’ my brother Dallin said with a smile. ‘Hi! How are you?’

I took a bit too long to answer. I blinked several times, as my brain processed this shock, on top of the unpleasant nausea provoked by the arrival of the envelope, before I remembered to smile back. ‘Dalliance,’ I said. If he could use childhood nicknames then so could I.

Dallin laughed and swept in to hug me. I was taken by surprise but didn’t try to stop him. Over the past couple of years, I’d become used to people hugging me, whether I wanted them to or not. Plus, it gave me another moment to deal with the fact that he was back, suddenly, inexplicably.

‘What on earth are you doing here?’ I asked into his shoulder.

Dallin pulled away, although he kept hold of one of my hands. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘I should’ve called. I’ve got a million excuses why I didn’t.’

I kept the smile on my face. Yes, I thought. I’m sure you do.

‘Here.’ Dallin took a step back. ‘This is Cora.’

I’d been so fixed on Dallin I’d barely noticed the woman who hovered awkwardly nearby. She looked as if someone had stapled her feet to the floor to keep her from fleeing. As she made eye contact she flickered a smile. It looked like she’d coached herself to smile at strangers. Honestly, that made me warm to her. It looked like we both knew the difficulties of social interactions that everyone else took for granted.

‘Thank you for this,’ Cora said, with another flickering smile.

I frowned, but Dallin was already leaning past me to look into the house. ‘Wow,’ he said, ‘the place is going great. I love the … those, y’know, those flowers there.’

He was pointing to the vase of sweet peas I’d placed on the phone table. ‘You should come in,’ I said, standing aside, because that’s what was expected of me.

Dallin stepped into the hall. ‘That’s brilliant, thank so much. Hey, I’m glad you kept the wallpaper, Mum always loved that colour.’

It was so familiar, the flow of thought and speech that characterised Dallin. Hearing it again, in this house, was a weird mix of jarring and comforting. The house was missing voices, I realised. The hardwood floors and high ceilings cried out for warm conversation and soft laughter. I hadn’t been able to provide either recently.

I ushered Dallin into the kitchen. The woman, Cora, followed. Briefly, I wished today had been the day for tidying the downstairs rooms rather than the bedrooms. It wasn’t like the place was a mess, just not as spotless as it might’ve been. I picked up a pile of magazines from the kitchen table then, realising there was nowhere better to stash them, put them back down.

‘The kettle’s just boiled,’ I said. Although, now I thought about it, I would need to boil it again, with enough water for three. ‘And – I don’t have any coffee. Or tea. I mean, I’ve got herbal tea. Peppermint. Or mint. Or spearmint.’

‘Tea sounds great,’ Dallin said. It was likely he’d only heard half of what I said. He was making a slow circuit of the room, examining everything. He studied the fridge magnets as if they held the secrets to the universe. I was glad I’d brought him and his friend into the kitchen rather than the sitting room. I couldn’t have coped with Dallin examining Beth’s ceramics with that somehow mocking, supercilious smile on his face. At least there was nothing in here except those stupid magnets, most from places me and Beth had never been.

I busied myself with the kettle and tried to gather my thoughts. Dallin was here. That was unexpected, to say the least, given it was six years since he last set foot in this house. But what could I do, tell him he wasn’t wanted? Shut the door in his face? Maybe I should’ve. But when I considered it, I almost felt Beth poking me between the shoulder blades. She never would’ve tolerated me acting like that towards my brother. Even if Dallin deserved it, and a million times more.

‘What were those kinds of tea again?’

I jumped. I hadn’t expected Cora to appear at my elbow. ‘Sorry?’

‘The teas.’ Cora tried another smile. This one didn’t look like she’d practiced it. ‘Three types of mint, right?’

‘Yeah. The peppermint is shop bought, but the mint and spearmint are from the garden.’

‘Like, leaves?’ Cora’s eyes crinkled. Her blonde hair was cut into bangs which fell forward whenever she dipped her head. Her ears had five or six piercing holes each, although she wasn’t currently wearing earrings.

‘Leaves. Yeah.’ I tucked my own hair behind my ears. I hadn’t showered that morning or done anything more with my hair than pull it into a messy topknot with tangled strands hanging down on all sides. All at once I was aware of how I must look to outsiders. I’d got used to no one seeing me for days at a time. ‘I’m sorry I don’t have any proper tea.’

‘It’s okay. I can’t have proper tea anyway.’

‘No? Why not?’

‘Because proper-tea is theft.’ Cora smiled, a little wider, a little more genuine, with a shrug that acknowledged the pun but refused to apologise for it.

I laughed. ‘So … mint?’

‘Sounds good. Thank you.’

I fished two extra cups from the cupboard. ‘So, why are you—?’

‘I can explain all that,’ Dallin said. He adjusted a seat at the kitchen table before sitting down.

Immediately he looked at home. Which was fair enough, I thought, since technically this had been his home before it was mine. The thought caused a twist of discomfort deep in my stomach. If Dallin had stayed, instead of running, it might’ve been him living here instead of me. I might’ve never had those beautiful years here, with Beth.

‘Cora’s looking for her sister,’ Dallin said.

I crinkled my brow. ‘Oh?’

‘Simone went missing twenty years ago,’ Cora said. Her attention stayed on my hands, watching as I made the tea, as if eye contact was too difficult right then. ‘She was fifteen. I was only nine. We never found out where she went.’

Dallin fidgeted in his seat. It was obvious he wanted to tell the story. ‘Cora thinks—’

‘I’ve been trying to put together what happened to her.’ Cora’s voice was soft but she spoke over Dallin with ease. ‘Trying to … piece things together. I’ve spent a lot of time chasing down vague hints and old clues. The police were involved at the time, I guess, but not for very long. Simone ran away. Nothing more to it than that. If she didn’t want to be found …’ Cora shrugged one shoulder. There was a softness to her movements as well. I got the sense she’d said these words a dozen times or more, and she’d become used to crushing the emotion so her voice didn’t shake, so now there was no inflection to her words at all. ‘It was only recently I started asking questions. My parents refused to talk about it.’

I stirred the mugs and scooped the leaves into the compost bucket. I wasn’t exactly sure why Cora was telling me all this. But I was used to people telling me their stories. It seemed to come with the territory. I had lost someone I loved. Apparently that meant other people needed to tell me their own traumas.

‘We know she went north.’ Cora took one of the mugs from me with a grateful half-smile. ‘The night Simone left home, she was caught on CCTV, getting onto a train. After that, she vanished. Never seen again.’

‘I’m sorry.’ I said it automatically, even though it always annoyed me when people apologised. Everyone’s sorry. It goes without saying. But even so, the quiet sadness in Cora’s expression made something twinge inside me. I’d spent so long pretending to be hardened, careful not to feel anything in case it set off the tsunami inside me. As harsh as it sounded, I didn’t want to feel sad over Cora’s story. I wanted to stay as I was. Feeling nothing.

‘Tell her the rest,’ Dallin said. There was a bright excitement in his eyes that he tried to hide.

‘There was a possible lead,’ Cora said. ‘Someone thought they saw Simone getting onto a ferry at Heysham. The police checked the CCTV at the time.’ She looked away to conceal the haunted look in her eyes. ‘They told me it showed a girl who was about the right age, right height, wrong clothes, but that doesn’t prove anything either way, does it? She could’ve changed her clothes easily enough. And the camera was pointed the wrong way. The police said they couldn’t see her face. And, of course, they didn’t bother keeping the footage on file, so I have to take their word for it.’ She blew on her tea to cool it. ‘Anyway, the footage wasn’t enough for the police. They looked into it – at least, they said they did. But they never found her here. Or anywhere else.’

I glanced at Dallin. From the look on his face, he was expecting something from me. But I couldn’t see what Cora’s story had to do with me.

Cora also frowned, looking hesitant again. ‘Did … did Dallin tell you this? He told you, right?’

Dallin said, ‘I sent you an email, Rose. Did you get it?’

I rolled my eyes. ‘What on earth made you think that was the best way to get in touch with me?’

‘I don’t know. Everyone does everything by email.’ Dallin raised his hands in weak apology. ‘I figured it might be a bit much for me to call you out of the blue.’

‘But turning up on my doorstep, that’s fine?’

Cora set down her mug. ‘I’m sorry. I had no idea … I thought you’d invited us here. I wouldn’t have … I’m sorry.’ She picked up her bag from the chair when she’d left it.

‘Wait. Cora, wait.’ Dallin intercepted her before she could walk out. ‘It’s okay. Rosie, it’s alright that we’re here, yeah? I’m sorry you didn’t get my message. But we’ve both come a long way. You need to hear what Cora’s got to say.’

He looked at Cora, expectant. He was still hanging onto her hand, like he’d hung onto mine at the door. Cora had her bag on her shoulder. It was obvious she wanted to stay, for whatever reason, but she was also reluctant to intrude where she wasn’t welcome. I knew how she felt.

Cora sighed. ‘I think you found my sister,’ she said to me.

‘I—?’ I frowned. ‘You think she’s living over here somewhere?’

‘No, I—’ Cora tucked a strand of blonde hair behind her ear. ‘I think you found her. When you were a kid, when you were out in the marshes.’

Realisation dawned. ‘Oh my God.’ I looked at Dallin, aghast. ‘You told her about that?’

‘It was on a website.’ Cora rooted in her bag for her phone. ‘I can find it for you. I read about the skeleton you found. Just near here, right?’

‘Um. Right.’ I couldn’t get my brain back in gear. ‘It was in the curraghs …’ I half-turned to gesture through the kitchen window, but lost what I was trying to say. ‘You read it on a website?’

‘It’s more of a forum,’ Dallin said. ‘There’s a lot of stuff about myths and urban legends and, y’know, that sort of stuff. Big cat sightings. There’s a page about your story.’

Cora held her phone out to me. The screen showed a black screen with white text that wasn’t formatted properly for mobile phones. It made me immediately think, I’d love to show this font to Beth, she’d hate it. Beth had been a keen blogger, right up to the end, and nothing wound her up more than white text on a black background.

I almost smiled, until I remembered what I was reading.

I skimmed the text. As if reading it fast might protect me. The page consisted of several long paragraphs and a few stock photos of the curraghs – at least, I figured that’s what they were, but the pictures were loading one line at a time on Cora’s phone. I sped-read through a slightly glorified account of how I’d found the body. It matched the story I’d told dozens of times to dozens of people over the years, with a few embellishments that hadn’t happened, and a few that I myself had forgotten. It was shocking to see it all written down in white and black.

‘People … people believe this?’ I scrolled up and down the page. ‘They believe me?’

‘Why wouldn’t they believe it?’ Cora asked. A brief flicker of anguish crossed her face. ‘Are you saying it’s not true?’

‘No, no. It’s just … no one ever believed me.’ I couldn’t help but laugh in disbelief. ‘Fifteen years I’ve been telling this story. No one ever believed me. And now apparently there’re people talking about it on the internet.’ I scrolled to the bottom of the post and skimmed the comments. ‘People believe me.’

‘Don’t ever read the comments, Rose-Lee,’ Dallin said. He took the phone off me and gave it back to Cora. ‘But sure, yeah, of course people believe you. They always did.’

I could only laugh again. Did he really think that? Wasn’t he paying attention when people were quietly shaking their heads and catching each other’s eyes over the top of my head? Had no one told him about the months when our dad had kept me out of school, when I was having bad dreams every night?

‘The timelines fit,’ Cora said then. ‘Simone disappeared in June 1999, and you found the skeleton in August 2004. That’s right, yeah? It could be her.’

‘You think …?’

‘I think you found Simone, yes. Possibly.’ Cora was trying hard to hold back the hope, I saw. How many years had she spent chasing fruitless leads and false hopes? ‘There’s a chance it could be her. I mean, it has to be someone, right?’

I examined my hands because I couldn’t look at either Dallin or Cora. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘I don’t know what to tell you. It was so long ago.’

‘You don’t remember it at all?’ Cora asked.

I couldn’t bear how the woman was staring at me. ‘I remember, sure. But it was fifteen years ago, and I was a kid. I don’t think I can tell you anything that isn’t on that website there. I’m sorry.’

Dallin started to say something else, but I turned away quickly and walked to the back door. I was overwhelmed – by Dallin coming back into my life, by Cora, by the past getting dredged up. I couldn’t deal with any of it.

I opened the back door and stepped outside.

Chapter 3

The sun was going down, casting long shadows into the back garden. I followed the path to the rear wall. There was a bench, sheltered beneath the sweet pea trellis, which only caught the sun at this late stage of the day. I rarely came down here anymore. Weeds had sprung up between the flagstones. I laid my hands on the rough limestone of the wall at the back of the garden; felt the coolness of the day against my palms. The smell of the curraghs was strong but not unpleasant, just a warm green scent that slowed my heartrate and smoothed out my tangled thoughts.

How many times over the past few years had I come here to calm down? Whenever I’d woken in the early hours and been unable to get back to sleep. Whenever me and Beth argued. On the day Beth got her diagnosis, when I’d realised I couldn’t cope. I had come here. Looking for something that could root me to the ground.

On those occasions, when nothing in the real world made sense, I would stand with my palms on the cool stone wall, and whisper to the ghost of the skeleton I’d found.

It’d started when I was still young, maybe three or four months after I found the skeleton. No one else would listen to me. Beth went to a different school, so I only ever saw her outside term time, and I missed her support desperately. It felt like the only person who might possibly know what I was going through was the person who’d got lost and died out there in the wetlands. When it got too much for me, I would beg my dad to let me stay with Mum for a few days, and then I would come down to the end of her garden like this.

I’d often imagined who the person in the curraghs had been. They’d had a life, a name. In the absence of the truth, I’d invented details. I pictured a girl my own age, wild and windblown, barefoot, running through the curraghs. I’d even given her a secret name: Bogbean, like the tiny white flowers that had blossomed in abundance around the gravesite. Sometimes I’d whisper the name aloud, into the silence of the evening air, but I’d never told it to anyone.

Good thing too. Otherwise it’d be on that stupid website right now.

My mouth twisted. Bogbean, the lost girl in the wetlands, had always belonged just to me. For fifteen years, whenever I needed to ground myself, I would speak my fears, aloud or inside my head, to Bogbean. Sometimes I imagined I heard the whisper of her answer.

‘Simone,’ I murmured now. ‘Is that your real name?’

There was no answer except the wind in the trees.

Everything had become so weird and so different, in the space of an evening. All of a sudden, Bogbean had a possible name, a possible life, family, friends. She was no longer a figment of my imagination.

‘Who are you?’ I murmured. If I half-closed my eyes, I could imagine Bogbean at my side, just beyond my peripheral vision, leaning her bare forearms on the top of the wall. But she said nothing, not even a whisper or a faint shrug. Right now, no one had any answers.

I heard the back door open as someone else came outside, but I didn’t turn around. I shut my eyes and breathed the cool air.

‘Hey,’ Dallin said from behind me. ‘You okay?’

‘Sure. Why not?’ I sighed, then turned to face him. I had a moment of disconnect, because I remembered him as a gangly teenager charging around this garden, leaping the flowerbeds like they were hurdles in his way. Now he looked awkward and out of place in what should’ve been his home. He kept his shoulders hunched, and avoided looking at the twisted trees beyond the back wall of the garden.

‘I’m sorry.’ Dallin lifted his hands in a shrug. ‘I thought you got my email. I didn’t mean to rock up here without warning. I know you don’t like that sort of shit.’

‘I just … I don’t understand why you’re here.’ I gave him a shrug of my own. ‘How did Cora even find you?’

‘We met on the forum. I stumbled onto it a while ago, and, y’know, obviously I was interested, because there was at least one person on there who remembered,’ Dallin flapped a hand at the curraghs, still without looking in that direction, ‘all this. I ended up chatting to some of the folks. That’s how I met Cora.’ He came to stand next to me, turning so he could lean his back against the wall, facing the house. ‘I told her I knew about the curraghs legend first-hand. I mean, obviously, that wasn’t something I should’ve done. There’s a lot of crazy people on forums like that. And when Cora told me her story …’ He put his hands in his pockets. ‘I had to take it with a pinch of salt, you know? I was okay with messaging her and hearing her story, but I was ready to bail if it turned out she was one of the crazies.’