Полная версия:

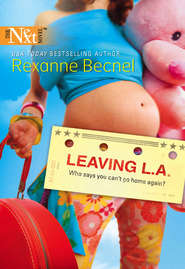

Leaving L.a.

So Alice could call her husband and all his kin, too. But she wasn’t getting rid of me until I had my money.

I heard voices from inside the house. Daniel was yelling at his mother and she was yelling back. But I couldn’t see them through the window. Well, it was my house, too, wasn’t it? So I got up and walked inside.

“…it’s still a lie,” Daniel shouted down at his mother from halfway up the stairs. “A lie of omission. Just like you said I did when I told you I was going to New Orleans with Josh and his big brother but didn’t tell you we were going to the Voodoo Fest.”

“That’s different,” Alice retorted. “You knew if you asked me to go to that Voodoo thing that I would say no. That’s why you didn’t tell me, and that’s why it was still a lie.”

“And you thought I would approve of you pretending you didn’t have a sister?”

Good point, kid. I crossed my arms, waiting for Alice’s reply. But when Daniel’s eyes shot to me, she turned around, too. She was shaking. I could see it on her pale face. It should have made me happy, seeing my Goody Two-shoes sister caught in a lie. Instead it made me vaguely uncomfortable. I didn’t care if she felt bad. But some small part of me didn’t want to make her look bad in front of her son. I remembered how awful it used to feel when my mom pulled some monumental screwup, some embarrassing public incident that I couldn’t overlook even with my hands over my eyes and my thumbs in my ears.

“She thought I was dead,” I blurted out. “Okay? I’ve never been very good about keeping in touch, so…” I shoved my hands into the back pockets of my jeans and shrugged. “You might say we’ve never really been close. But now I’m back,” I added, switching my gaze to Alice. “So where should I put my stuff?”

When she just stared at me with big, round—scared—eyes, Daniel answered for her. “There’s plenty of room upstairs. Two guest rooms plus mine and a study.”

“Daniel—” Alice raised a hand to him, then let it fall in the face of his anger and hurt. His mother had lied to him. I guess that hadn’t happened before. Lucky boy.

“Fine,” I said into the tense standoff between them. “It won’t take me long to unpack. Then maybe you and I can have a nice long talk, Alice, and catch up on the past—” twenty-three “—few years.”

I was just lugging my second-to-last load up the front steps—why had I brought so many records and books?—when a third car turned into the yard. A burgundy Oldsmobile. An old man’s car, and given that the guy who got out had a full head of white hair it seemed like I’d guessed right.

I ignored him and let the screen door slam as I went inside. Once I got everything in my room, I planned on taking a bath. Then I was getting the hell out of this house for a while, because already it was giving me the creeps. It would take more than a few coats of Sunny Yellow and Apple Green latex to paint out the stains of my miserable childhood.

Outside I heard Tripod barking, then a man’s voice yelling, “Shoo. Get away!” Then, “Alice. Alice!”

Upstairs I looked at Daniel’s closed bedroom door. He’d been in there ever since his fight with his mother. Downstairs I heard Alice fussing at Tripod. I guess the man of the house got inside unscathed. I dug around for a dog biscuit before heading downstairs for the last box. Tripod deserved a reward for sticking up for me.

In the front parlor Alice sat hunched over on an elaborate settee, her husband next to her with an arm around her bowed shoulders. When he heard me on the stairs, he looked up and glowered at me. “Is this any way to treat your only sister?”

I planted one fist on my hip. “I’ve ignored her for twenty-three years and she’s done the same to me. How does that make me the villain and her the victim?” Then I strode forward and stuck out my hand. “Hi, I’m Zoe. And you must be…”

By now Alice had bucked up enough to speak for herself. “This is Carl Witter, a…a friend of mine.”

A friend? He looked a bit possessive of her to merely be a friend. And he ignored my hand. “Oh,” I said, pulling it back. “A friend. Where’s your husband?”

If possible, Carl’s pale eyes turned even colder. “Reverend Collins died thirteen months ago,” he bit out. “Which you would have known—”

“If she had told me,” I threw back at him. Alice had been married to a minister? I pushed that question aside. “I guess that makes you the new boyfriend.”

“I’m her friend,” he bit out. “And I’m not about to let you take advantage of her sweet nature, especially with an impressionable young man in the house.”

“An impressionable young man who didn’t know till now that he had an aunt.” The more I thought about that fact, the madder I got.

He leaped to his feet. “Given the aimless, Godless life you’ve led!”

“Stop it, Carl,” Alice begged, tugging on his arm.

“You don’t have to let her stay here,” he told her. “This is your home.”

“Which happens to be half mine,” I said.

That stopped him cold.

“Look,” I said before he could start up again. “Why don’t you and Alice go back to whatever you were doing. I can finish moving in without any help.” Then flashing them a smug smile, I flounced out of the house.

From behind a closed door—what used to be the “Meditation Room” when we were kids but what had actually been the “High Way Room” for getting loaded—I heard Angel yapping. From his spot on the porch, surveying his new domain, Tripod let out a warning bark.

“Good boy,” I told him, rubbing his ears the way he liked. “I think we’ve each won the first skirmish.” It was mighty interesting that, considering she thought I was dead, Alice and her creaky boyfriend sure seemed to know all about my “aimless, godless life.”

I straightened up and looked around me. The porch, the house, even the grounds looked nothing like how I remembered. But the ghosts of my childhood were still there, waiting to jump out at me. God, I hoped it didn’t take long for Alice to give me what was my due. I didn’t think I could last very long in this haunted house of ours.

CHAPTER 2

I hung up my clothes, put the folded things into the pretty oak dresser, lined up my shoes in the bottom of the closet and stacked the boxes of records and books in the corner behind the bed.

“Now what?” I said to the world at large. I’d accomplished the first part of my plan. That had turned out to be the easy part. Now I needed a plan for Part Two.

My stomach gurgled and I rubbed one hand over it. “You stay here,” I told Tripod, who’d already stretched out on the faintly dusty pine floor. “Guard my stuff while I…”

Go somewhere. Do something. I wasn’t sure what.

All I knew was that I wasn’t sitting up here in the room my mother had called the Venus Trap. I’d once seen three women and two men doing stuff to each other here that no eleven-year-old should ever be exposed to. The room was painted pale blue now, with eyelet curtains framing the two windows and an old-fashioned chenille bedspread covering the pretty iron bed. But I could see the black and hot-pink walls beneath this pretty facade as clearly as if the paint was bleeding through.

“Ugh.” I shuddered and closed the door behind me. Directly across the hall Daniel’s solid door seemed to beckon me. I knocked, a short lilting rhythm. After a minute he cracked the door.

“Hey. Listen, I’m going out. You know, to drive around and check out the changes in town.” I made that decision barely a split second before the words spilled out of my mouth. “You need anything? A ride anywhere?”

He shook his head, not meeting my eyes. But he didn’t close the door in my face either.

“Look, Daniel. I didn’t come here to make trouble between you and your mother. She and I…well, let’s just say we weren’t raised in a real close family. I’m sure she has her reasons for not telling you about me.” Lousy reasons but reasons all the same.

“But she lied to me.” He lifted his eyes—Mom’s eyes—to me.

“Look, kid. Everybody lies. All the time.”

“That’s not true.” When I only shrugged, he said, “Well, they’re not supposed to.”

“But they do. The trick is to figure out their motive. Are they trying to hurt you with the lie or just trying to help themselves out of a bad situation?” Then for some stupid, maudlin reason I added, “Or maybe they’re lying because they think it will somehow help you.”

“Well, it didn’t help me.” He gave me this long, steady look. “Why’d you decide to come home now?”

I didn’t want to say. It was one thing to demand what I was owed from Alice. It was another thing to discuss it with her kid. “I figured twenty-four years away would have been too long. So,” I went on. “Do you need anything while I’m out?”

He hesitated only for a second. “Maybe I will take a ride with you. To my friend’s house.”

“Okay. Let’s go.”

Tripod started to howl. How he knew I was leaving the premises was beyond me. Daniel gave me a questioning look. Normally I’d take the dog, too. But I didn’t trust Carl Witter not to take my stuff and throw it outside. I knew Tripod wouldn’t let him get past the door.

We didn’t see anyone in the living room. “I’m going to Josh’s,” Daniel called toward the kitchen.

No answer.

“She’s not going to be happy when she finds out I drove you,” I pointed out as we climbed into Jenny.

“I’m fourteen, not four,” he muttered. “Almost fifteen. I can take care of myself.”

“Okay then.” I started up Jenny’s cranky engine. “Which way?”

Driving down the old roads of my childhood was like negotiating a foreign country. Like a Twilight Zone episode where everything was so strange and yet somehow familiar. The town square and St. Brunhilde’s church, and the Landry mansion were familiar. The P.J.’s Coffeehouse in the old Union Bank building, the Wendy’s on the corner of Barcelona Avenue and the Walgreens opposite it were all new. The park that meandered along the river was the same. Bigger trees and bigger parking lot but otherwise the same. That’s where that stupid Toups kid and his friends had chased me once, wanting to know if it was true that hippie kids didn’t wear underwear. I’d jumped into the river to escape them and nearly drowned.

Mother had laughed when I’d finally got home, shivering in my wet clothes. I’d shown them, she’d chortled.

Her boyfriend at the time, Snakie somebody or other, had stared at my fourteen-year-old breasts beneath my clinging knit top and promised to get even for me. And he had. The old sugar-in-the-gas-tank trick. I heard Bonehead Toups had to go back to his bicycle. Sweet justice, literally.

But of course, it had a downside. Snakie had wanted a sweet little reward for being so heroic. A reward from me, not my mom.

Unfortunately for him, after the river incident I’d checked out a library book on self-defense for women. That knee-to-the-groin business really works. He moved out the next week.

“Turn left up there, by the gas station,” Daniel said, bringing me back to the present. We went down an old blacktop to just past where it turned to gravel. “There.” He pointed to a pair of shotgun houses with a rusty trailer parked farther behind them.

“Do you need me to pick you up later?” I might as well ingratiate myself with him before his mother turned him completely against me.

“No. Josh’ll give me a ride home.”

“This Josh is old enough to drive?”

He grinned. “He has a four-wheeler. We’ll take the back route through the woods.”

I grinned back. “Sounds like fun.”

“Yeah. But don’t tell my mom that part.” His grin faded. “She says it’s too dangerous.”

“It is too dangerous. But that’s what makes it so fun.”

“Yeah.” He slammed the door, then gave me a head bobble that I guessed passed for “thanks.” “See ya.”

Then it was just me and Jenny Jeep and my old hometown.

On the surface, Oracle, Louisiana, is just like every other small town I’ve ever been in: an Andy of Mayberry downtown, a big, brick elementary school, a couple of churches. It had more trees than most. And more humidity. I’d been in a lot of little towns, especially when I toured with Dirk and his Dirt Bag Band. I’d done everything on those tours: arranged the shows, driven the bus, collected the money. Collected the band too when they were too stoned to find their way back to the bus.

I hadn’t collected very much money for myself, though. I was Dirk’s girlfriend. What did I need with money?

His words, not mine.

That’s when I’d started my T-shirt and jewelry sideline. Small-town wannabe rockers and wannabe groupies had snapped them up. Too bad I hadn’t saved more of that money. But Dirk had thought what was mine was his, and he would have blown my profits on booze and drugs and music equipment. So instead I blew them on becoming the best-dressed rock band manager you ever saw.

Anyway, you see one small town, you’ve seen them all.

I turned onto Main Street. Creative street name isn’t it? That’s when I saw the library. Except for the white crepe myrtles flanking the front doors, it hadn’t changed a bit. There weren’t many places in this town I had good associations with; the library was one of them.

I parked in front of the newspaper office next door to the library. Through the paper’s front window I saw an old woman staring at a computer screen. So the Northshore News had gone high tech. With only a few keystrokes they could more easily report on this weekend’s softball tournament or the Jones’s fiftieth anniversary celebration. Woo hoo. Big news.

At least there weren’t any parking meters to feed. I jumped down from Jenny, locked the door and slammed it.

“You must be from out of town.”

Startled, I looked up. “Why do you say that?” I replied to this guy who had stopped in front of the newspaper office, his hand on the doorknob.

“You locked your car. People around here don’t do that.”

His comment shouldn’t have made me feel so defensive, but I guess I was feeling extra touchy today. Added to that I wasn’t in the mood to be hit on, especially by a guy who had to know how good-looking he was. “They don’t? Well, I’ve been mugged in a small town like this.” A drunk coming out of one of the Dirt Bags’ concerts, who got frustrated when I wouldn’t go home with him. “And had my car broken into.” Amps stolen out of the band’s bus.

I hiked my purse onto my shoulder and tossed my hair back. “So you see, I’ve learned not to be too trusting. Even in a nice little town like this.”

He tilted his head to one side. “Sorry to hear that.” He stared at me. At me, not my chest, for one long, steady moment, the kind of look that forced me to really look at him in return. If I were looking for a guy, he would have fit the bill just fine. If I were looking. Several inches taller than me, even in my heels. Wide shoulders, trim build. Not cocaine skinny like too many of the men I’ve known. Not self-indulgent fat like too many others. Which left the equally unappealing other third of men: probably a narcissistic health nut trying to stave off middle age.

“I’m Joe Reeves.” He stuck out his hand.

I didn’t want to know his name or to know him. But I had no real reason to blow him off. So I took his hand—big, strong and warm—and shook it. “Zoe Vidrine.”

“You visiting here, Zoe? A tourist?” he asked, once I’d pulled my hand free of his.

“Oracle gets tourists?”

“You’d be surprised. Oak trees dripping with Spanish moss. Natural spring waters. We have our own winery now and a railroad museum. Not to mention all the water sports on Lake Pontchartain.”

“That cesspool?”

“It’s clean now. Regularly passes all state requirements for swimming.”

“Gee, it all sounds so exciting.” But I softened my sarcasm by laughing.

He grinned. “That’s the point. It’s quiet and relaxing here. The perfect escape from the rat race.”

“Yeah? Well, we’ll see.”

“So you’re not a tourist. That means you’re visiting someone.”

I glanced away from his lean, smiling face. He was too smooth, too easy to talk to. Then I realized he’d been going into the newspaper office, and all my senses went into red alert mode. “You work here?” I gestured to the office.

“Sure do. Editor-in-chief.”

Editor-in-chief? Shit!

“Plus beat reporter, features reporter, obituary writer and head of advertising. We’re a small outfit, Wednesday and Sunday editions only.”

“Cool,” I said. But I meant just the opposite. The last thing I needed was for some local-yokel reporter to figure out that Zoe Vidrine was actually G. G. Givens’s ex-girlfriend Red Vidrine and try to make a big deal about it.

I shifted my purse to my other shoulder. As I did so, his gaze fell to my body. Just one swift, all-encompassing glance. But it was enough to remind me that he was a man like every other man in the world. To them I was just a hot babe who looked as if all she wanted was his leering, drooling attention. “Well. See you around,” I said. Then I turned and made for the library, my sanctuary when I was a kid, and hopefully my sanctuary now. I willed myself not to look back at him, but I knew he was watching. I felt it.

Inside, the library was cool and dim and so much like when I was a kid that a wave of relief shuddered through me. Same big wide desk; same art deco hanging lamps; same oriel window where I used to sit for hours reading everything from Seventeen Magazine to Alexandre Dumas to Shere Hite. I learned a lot about sex from Shere Hite. Too bad more men hadn’t read her.

Anyway, my oriel was just like I remembered except for new, dark green upholstery on the cushions.

I looked around. Mr. Pinchon couldn’t still be the head librarian. I approached the woman at the front desk.

“Can I help you?” She smiled like she really meant it.

“I was wondering, does Mr. Pinchon still work here? When I was a kid he used to suggest a lot of books for me to read.”

“Mr. Pinchon? I don’t know him. Oh, wait. He retired a couple of years ago before I started working here.”

“Oh.” I looked away. I shouldn’t feel disappointed, but I did. The one person who’d understood me, who’d cared enough to make sure I read across the spectrum. He’d made me a lifelong reader—and a sometimes writer. But of course he was gone. He was old back then. By now he was probably dead.

“Can I help you with anything else?” the librarian asked. “Do you have a current library card?”

“No.”

“Well, we can easily remedy that.” She handed me a pen and a registration form, and I started to fill it out. Until I caught myself. I didn’t need to advertise that I was in town. I’d planned all along to keep a low profile, to just swoop down, collect my inheritance and split.

Then why’d you tell that newspaper guy your name?

I slid the pen and paper back across the desk. “I’m just in town for a week or two. Um…could you direct me to the microfilm records, the ones for the Northshore News?”

“Sure. You know, their office is right next door if you need to talk to Joe or Myra. She’s worked there forever.”

“Thanks.” I gave her a bland smile. “How long has he been there?”

“Joe? Let’s see now. I think three—no, four years. He used to be a big-time reporter in New Orleans. For the Times-Picayune. But when he and his son moved here, he decided celebrity news wasn’t as exciting as it used to be.”

I stiffened in alarm. Celebrity news? That’s what he’d written about? Great.

“Well, I can see why he left it behind,” I said. “Most of it’s a lot of PR hype. But what I’m looking for…” I went on, wanting to change the subject “…is local news from the mid-eighties on.” I’d left town in 1983, Mom had died in 1986 and Alice had obviously married sometime after that. I wanted to see what had been said about the Vidrine hippie commune, how it had petered out and how Alice had changed everything. Because like it or not—like her or not—I had to admit she’d done an amazing transformation of the place.

Some time later the librarian—Kenyatta was her name—startled me as I hunched over a microfilm screen. “Sorry to disturb you,” she said. “But the library closes in fifteen minutes.”

“What time is it?”

“Quarter to six.”

I’d been here three and a half hours?

“Okay. Thanks. I’ll finish up here in a minute. What time do you open tomorrow?”

Right after she left I went back to the article I’d been reading about the christening of Daniel Lester Collins at the Simmons Creek Victory Church. The picture was grainy, but it was obviously Alice holding her newborn son. Next to her stood a gaunt, older man. Surely that wasn’t her husband?

But it was. The Reverend Lester Collins had presided over the christening of his firstborn child. He had a huge grin on his face.

And why shouldn’t he? He had a young, pretty wife who—knowing Alice—had probably done his every bidding. And she’d given him a son. For him, life must have been pretty damn good.

Had it been good for my sister?

As I left the library and headed up Highway 1082 to the farm, everything I’d read rolled around in my head. Mom had died of AIDS.

About three months before her death, her illness became public knowledge. In 1986 rural Louisiana that had been a horror too huge to ignore, and all sorts of hell had broken loose. There had been letters to the editor. Demands that the farm be quarantined, that the house be burned down to kill the germs. The American Civil Liberties Union in New Orleans had actually become involved.

By the time Mom died, only she and Alice were left on the farm. All Mom’s freeloading friends had split. There was no official obituary notice, but afterward there had been a slew of articles and more letters to the editor about the wages of sin and the plague festering at Vidrine Farms.

I frowned and turned down the azalea-lined driveway. How had Alice stood it? Why on earth had she stayed? And why, when she called, hadn’t she told me it was AIDS?

Then again, that wouldn’t have changed my reaction.

I sighed. Despite my carefully cultivated disdain for my spineless, mealymouthed sister, I had to give it to her. She’d showed them all in her own, do-gooder way. I would probably have sponsored a rock festival on the farm and invited the most offensive acts I could find. Then I would have ended it by making a giant bonfire out of that house.

I pulled to a stop and stared at the house now, so pretty and neat and innocuous-looking. I would have lit the fire gladly but not for the reason ranted about in that stupid newspaper. I would have burned it down for my own satisfaction, to obliterate once and for all the miserable childhood I’d lived in it.

The sun was sinking behind the house, casting it in soothing shadows, a photo-op for This Old House. I closed my eyes and rested my forehead on the steering wheel. Burning it down wouldn’t have helped. I would have loved doing it, watching the destruction, feeling the heat, smelling that scorched wood stench. But it wouldn’t have changed anything. I was the product of my rotten childhood, pure and simple. And nothing symbolic would change that.

But collecting my half of its value in cold, hard cash would go a long way toward easing my pain.

I slammed out of the car, resolved in my goal to just collect my due and get started on a new, normal life. From upstairs I heard Tripod’s mournful howl, and I spied his ugly snout pressed against the window glass. He probably needed to visit the nearest tree.

I trotted up the steps, crossed the porch and walked into the house—only to be confronted by Carl.

“The least you could do is knock.”

I ignored him. “We need to talk,” I said to Alice, who stood farther down the hall, in the doorway to the kitchen. “By the way, better collect your toy dog. I’m about to let Tripod out.”

“And that’s another thing,” Carl hollered up after me. “That dog is too big to be allowed indoors—”

He broke off when Tripod charged down the stairs in one big hurry. The dog leaped up, planting his one front paw on the front door, barking his impatience.