Полная версия:

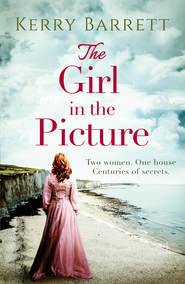

The Girl in the Picture

Dad still looked bewildered and later – when I went over and over the conversation (if you could call it a conversation when it was really only me talking) in my head – I saw the genuine confusion in his face, the hurt in his eyes, and it broke my heart. But at the time, all I thought of was that I’d been proved right.

‘For the first time in my whole life, I’m doing what I want to do,’ I said. ‘And it’s not what you want me to do but I’m going to do it anyway.’ I picked up my bag. ‘And you can’t send me away this time – because I’m going.’

Ignoring Dad’s shocked expression and Barb’s comforting hand on his arm, I threw my coat over my shoulder and marched out of the pub, and down the road to my car, where I sat for a while, sobbing quietly into my hands. I wasn’t sure what had just happened and I had a horrible feeling that I’d got everything wrong.

Chapter 3

I drove home from Kent in a bit of a daze, ignoring my phone as it lit up with missed calls from Dad. And I carried on screening our landline and my mobile – avoiding any calls from him and Barb – for the next few days while we packed up our house and said goodbye to our friends in London.

‘Phone him,’ Ben said as I was getting dressed ready for my last day in the office. I ignored him.

‘I won’t be late,’ I said. ‘I’m not going to stay for drinks or anything like that.’

I looked at my reflection in the mirror. Hair neatly twisted up and out of the way, smart suit, sensible shoes.

‘I’m going to throw this outfit away,’ I said. ‘And I’m going to cut my hair.’

‘Good for you,’ Ben said. He was still in bed because he’d got the day off to finish packing, sitting up drinking a cup of tea and reading a biography of a footballer I’d never heard of. ‘Phone your dad from the hairdresser’s.’

I scowled at him. ‘I’ll phone him when we’re settled,’ I said. ‘Invite him down for a weekend. It will be fine.’

But I wasn’t sure it would be.

As we pulled up outside the house on moving day, I felt my nerves bubbling away in my stomach. I knew what the house looked like, of course, but seeing it in real life, up close instead of peering at its roof from down on the beach, made it all seem – suddenly – like a very big decision for Ben to have made on my behalf. All of Dad’s warnings about the risk we were taking, and having no safety net were weighing heavily on my mind.

It wasn’t a pretty house, I thought, as I pulled the car on to our new drive. It squatted at the end of the lane, at right angles to the other houses, with its back to the sea. It was the back view we’d seen all those months ago from the beach – and the back view was a lot prettier than the front, I now realized. It was built from reddish brick, and it had three storeys and white-painted gables. It had a higgledy-piggledy extension on the side and mismatched windows.

It was about as far away as it was possible to be from the chocolate-box cottage everyone imagined when we said we were moving to Sussex. But Ben was adamant that it was completely right – even the fact that it had stayed empty from the time we’d spotted the to-let board from the beach until the time we’d been ready to move was a sign, he claimed. I heard him telling friends that it was exactly the house we’d have designed for ourselves if we’d had the chance. I hoped he was right and that Dad was wrong. My spontaneity seemed to have abandoned me now we were actually starting our new lives.

I pulled up the handbrake and Ben grinned at me. I smiled back. His enthusiasm was infectious and despite my worries, deep down I did feel like this was a new start for us. I peered out of the car window at our new home. The house had probably been quite grand once, but now it looked slightly forgotten and in need of TLC. Maybe we’d give the house a new lease of life, I thought. I’d even wondered whether, if we bought it, we could add a conservatory on the back where we could sit and look at the sea.

Ben grabbed my hand as I went to undo my seatbelt.

‘It’s not too late to change your mind,’ he said in a murmur so the boys wouldn’t hear. ‘We can turn round now and go back to London if you want.’

I felt a wave of nerves again. Now I’d given up work, Ben was going to be shouldering the financial burdens of the family. So far it had been fine, but there was a lot of pressure on him at the football club. They had a lot of very valuable players and the legs Ben was looking after were worth millions – or so he kept telling me. This was his big break and he had to make it work.

Meanwhile, after months and months of not writing anything, I’d told my editor, Lila, I was going to start. But I was regretting that a bit now because I had no ideas, even less motivation, and Lila was breathing down my neck desperate for words. I was worried Ben was putting too much pressure on himself and putting too much faith in the house. What if I couldn’t write any more? What if Ben’s job didn’t work out? Was it all a terrible mistake, just like Dad had warned me it could be?

I took a breath. ‘Of course I don’t want to go back to London,’ I said, as much to myself as to him, squeezing his hand. ‘This is absolutely the right thing for us to do.’

Ben looked at me for a second, then he squeezed my hand back. ‘So let’s move in,’ he said.

I leaned over to unstrap Stan’s car seat. ‘Everything’s going to work out perfectly,’ I said firmly.

‘In this perfect house, with this perfect family?’ Ben said, chuckling with what I thought was relief. Or maybe he was just as nervous as I was? ‘How could it not?’

He helped Stan clamber out of the car and then grabbed him for a cuddle. ‘What do you think, little man?’ he said. ‘What do you think of your new home?’

Stan whacked him on the head with a wooden Thomas the Tank Engine. ‘Nice,’ he said. ‘This is a nice house.’

Oscar yanked my hand. ‘Come. ON. Come on, Mummy.’

He dragged me out of the car and up the path.

‘Hurryuphurryuphurryup,’ he breathed as he pulled me along. I laughed in delight and threw the car key to Ben so he could lock up.

Stan wriggled out of Ben’s hug and raced to join his brother and me. I felt Ben’s eyes on us as he beeped the car doors and followed. We had to make this work, I thought. But he was right. How could it not?

‘The door should be open,’ Ben called.

Oscar grabbed the handle and it opened. ‘Mummy, Mummy,’ he gasped as we all fell through the front door. ‘Look at the staircase.’

‘Staircase, Mummy,’ Stan echoed.

‘Mummy, can we get a dog? Daddy said we could get a dog. So can we?’

I let myself be dragged around the house, laughing, as the boys and Ben fell over themselves to be the first to show me things.

‘Look, Mummy, there’s a fridge,’ said Oscar proudly as I admired the large, if slightly dated, kitchen.

Sunlight streamed through the windows, which were gleaming. The whole house was sparkling clean, actually. Ben said the estate agent – Mike – had arranged for it to be done as it had been empty for a while. It all shone in the sunshine and the house was filled with light but strangely all I felt was dark.

Ben was so proud as he showed me round; I could see he really loved the house. And me? Well, I felt a bit funny. Like it wasn’t really ours. Probably I just had to get used to it; that was all. Get all our belongings in there. Settle down. It just all seemed a bit temporary and that made me nervous.

‘It’s wonderful,’ I said, squeezing his arm. Suddenly desperate to get out of there, I muttered something about seeing the garden, and walked out of the French doors on to the lawn.

Listening to the boys’ excited voices as they tore round the house, I wandered down to the end of the garden, breathing deeply, glad to be out of the house.

There was a line of trees at the end of the lawn, and behind them a rocky path led down to the narrow, stony beach where the waves crashed on to the shingle.

‘Amazing,’ I said out loud. It was incredible. I thought of our London house, with its tiny garden where the boys roamed like caged tigers. Here they could run. Burn off their energy in safety. Swim in the sea. Collect shells. It would be idyllic, I told myself. A perfect childhood in the perfect house.

Thinking of the house again made me shudder. I turned away from the sea and walked back across the grass towards the back door, but I couldn’t quite bring myself to go inside. Instead I dropped down on to the lawn and sat, cross-legged, looking back at the house.

From the back it wasn’t so ugly. It was all painted white – in stark contrast to the red brick front – so it dazzled in the bright sunshine and looked less thrown together. I was being silly, I thought sternly. It would be lovely living close to the sea and the light was beautiful. Maybe it would inspire me to write.

The sun went behind a cloud and I gazed up at the top of the house, trying to work out which windows belonged to the room that would be my new study.

There were two large windows on the top floor on this side, which I knew would bring light flooding into the room, and one smaller window. I suddenly felt excited about things again, so I decided to go upstairs and check out the room – Ben had been so enthusiastic and I wondered – hoped – if some of his glee would rub off on me and perhaps kick my writer’s block into touch. But as I got to my feet, a movement at the top of the house caught my eye.

I glanced up and blinked. It looked like there was someone up there, framed in the attic window. I couldn’t see them clearly but it certainly looked like a figure.

My mouth went dry. ‘Ben,’ I squawked, hoping it was him up there. ‘Ben.’

Ben appeared at the French windows from the lounge. I looked at him then looked back up at the window. There was nothing there. I’d been imagining it.

‘What’s the matter?’ he said. ‘What’s wrong?’

I forced a smile. ‘I thought I saw someone upstairs,’ I said. ‘I’m seeing things now – I must be tired. Where are the boys?’

Ben stepped into the garden, blinking in the bright sunlight. ‘They’re in the kitchen,’ he said. ‘Where did you see someone?’

I pointed to the window, and as I did, the sun came out from behind the cloud and reflected off the glass, dazzling me. ‘Must have been a trick of the light,’ I said, squinting.

‘Must have been because there’s no one there.’ Ben nudged me gently. ‘Come inside and have a cup of tea – I’ve unpacked the kettle. We’re all tired and you could do with a break.’

Chapter 4

I let Ben guide me back to the house, telling myself it had been a trick of the light. There was that thing, wasn’t there, where your mind makes people out of abstract shapes? It must have been that.

While Ben made tea I chatted mindlessly with the boys, reminding them about the beach, and wondering if they’d like to go for a paddle in the sea tomorrow. The house seemed too big and echoey without our furniture – where were those removal men?

I looked round. Rationally I knew this house was as ideal for our family as the garden was. It was just so different from our old place, and suddenly the leap we’d taken seemed way too big for us to cope with.

‘Shall we explore some more?’ I said, desperately trying to muster up some enthusiasm. The boys jumped at the chance and raced off upstairs. Ben and I followed more sedately. I was keen to get into the studio, but also nervous about what I might find; I was still unsure whether I’d seen someone at the window.

As the boys and Ben discussed which room Oscar wanted and which room would be best for Stan, I took a deep breath and climbed the stairs to the attic.

It was empty – obviously – and it was also perfect. I grimaced a little unfairly at Ben being right about that, too. It was a big room, sloping with the eaves of the house to the front and with two huge windows to the back – the window where I thought I’d seen the figure standing was on the left. It had bare floorboards, painted white. The walls were also white, emulsion over brick, or over the old wallpaper in parts. It was cool and airy.

I wrapped my hands round my mug of tea and wandered to the window. The view was breathtaking and the light was incredible. It seemed to me like an artist’s studio and I wondered if a former resident had painted up here. Surely someone had? I could think of no other use for the room. It wasn’t a bedroom, or a guest room. The staircase to get up to the room was narrow and the door was small. I doubted you’d get a bed up there unless you took it up in pieces and built it in the room.

I looked down at the lawn where I’d sat earlier and glanced round to see if anything in the empty room could have given the appearance of a person. There was nothing.

Perching on the window ledge, as I always did back in London, I examined the studio with a critical eye. It wasn’t threatening or scary. It was just a big, empty room. A big, empty, absolutely lovely room. What I’d said had been right: the figure must have just been a trick of the light. The sunshine was so bright in the garden, it could have reflected off the old glass in the window …

My thoughts trailed off as I realized something. From downstairs, I’d seen two large windows and one small. Up here, there were only two large windows. That was weird.

Putting my empty mug on the windowsill, I went out into the hall. As far as I could tell there was nothing at the far end. No extra room, or door. The hairs on the back of my neck prickled. This was a strange place.

Tingling with curiosity – and feeling a little bit unsettled – I went back downstairs to the bedrooms.

Ben and the boys were in the biggest room, which also looked out over the garden. Stan’s face was flushed and Oscar looked cross.

‘Mummy,’ he said as I walked in. ‘I am meant to have this room because I am the biggest but Stan says he has to have it because he wants to watch for pirates on the sea.’ His face crumpled. ‘But I want to look for pirates too.’

‘Bunk beds,’ I said. ‘We’ll get you bunk beds and we can make them look like a ship. Then you can sail off at bedtime and look for pirates together.’

Ben shot me a grateful glance and I smiled at him.

‘I’ve found something funny,’ I said, casually. ‘Can you come and see?’

Ben and the boys followed me up the narrow, rickety stairs to the attic room. We all stood in a line in the middle of the floor, staring out at the sea.

‘Look,’ I said. ‘When I was in the garden, I could see three windows in this room. There were the two big ones, and a little one – remember?’

Ben nodded, realization showing on his face. ‘But up here you can only see two windows,’ he said. ‘That’s mental.’

He went over to one of the windows and pushed up the sash, but it was fixed so it couldn’t open too far. ‘I thought I could lean out and see the other window,’ he said. ‘But I won’t fit my head through that gap.’

‘My head will fit,’ said Oscar.

‘No,’ Ben and I said together.

Oscar looked put out. ‘Maybe the little window is on next door’s house,’ he said.

Ben ruffled his hair. ‘Good idea, pal. But next door isn’t attached to our house. It’s not like in London.’

I was standing still, staring at the windows, feeling a tiny flutter of something in my stomach. Was that excitement?

‘You’re loving this,’ Ben said, looking at my face. ‘One sniff of a mystery and you’re in your element.’

He had a point.

‘Oh come on,’ I said. ‘A missing window? Don’t pretend you’re not interested.’

He smiled at me, not bothering to deny it.

‘Maybe there’s a hidden room,’ I said. ‘Maybe it’s a portal to Narnia.’

‘Or maybe there’s a ventilation brick in these old, thick walls.’

I snorted. ‘Don’t ruin it.’

Ben grinned. ‘I think we’d notice if the house was bigger on the outside than the inside,’ he said.

‘Like the Tardis,’ Oscar shouted in glee. Then he frowned. ‘But the other way round.’

I started to laugh. ‘I don’t think you guys are taking this seriously enough,’ I said, mock stern. ‘This could be something very exciting.’

Ben nodded. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘I’ve got this.’

He went over to the wall at the far end of the room and tapped it. Then he tapped it again in a different place, and again and again. I sat down on the floor, with Stan on my lap, and watched.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked eventually.

Ben looked at me in pity. ‘I’m checking to see if the wall sounds hollow,’ he explained. ‘If it sounds hollow then perhaps there’s another room behind here.’

‘Does it sound hollow?’

There was a pause.

‘I don’t know,’ he admitted.

I laughed.

‘Well then we need to compare it to the other walls,’ I said.

And then there was chaos. Stan and Oscar raced around, banging the walls, as Ben and I listened and said, ‘hmm’. We had no idea what we were listening for, but it was fun. The boys shouted, and we laughed, and I thought that maybe everything was going to be okay.

Chapter 5

1855

Violet

I almost slipped on the rocks as I struggled down to the beach, even though I’d been that way hundreds of times before. My easel wasn’t heavy, but it was cumbersome, and the bag of paints and brushes I was carrying banged against my legs. Eventually, though, I found my perfect spot. It was warm, but the sun wasn’t too dazzling and I breathed in the sea air deeply.

Working quickly, I set up my easel and pinned my paper down securely. I arranged my paints on the rock behind me, as I’d planned, pushed a stray lock of hair behind my ear, and picked up my brush. I paused for a second, appreciating the moment; I was completely content. This was how I’d dreamed of working for – oh months, years perhaps. I finally felt like a real painter. My room in the attic was wonderful, of course, and I would always be grateful to Philips, the lad from the village who did all the odd jobs around the house and garden and who’d helped me secretly create my own studio.

I frowned, thinking of Father, who didn’t like me to draw. He said it was vulgar. He wanted me to marry and lead a normal life. A normal, boring life, I thought. A mundane life. A life with no purpose.

But out here, breathing in the sea air, I felt like I had a purpose. I was telling a story with my work and it seemed it was what I’d been waiting for. For years all I’d drawn was myself – and various kitchen cats. Endless self-portraits that helped my technique, undoubtedly, but – if I was honest – bored me stupid.

Then, one day, I’d picked up Father’s Times, and read about a new group of artists known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They painted stories – Bible stories, tales from Shakespeare, all sorts – and they used real-life models to do it. It had been like a light turned on in my mind. Suddenly I knew what I wanted to do – I wanted to be like those artists. Paint like those artists. Live life like those artists.

After that, I devoured any articles on the Pre-Raphaelites in Father’s newspaper, and I read the Illustrated London News, and even Punch, when I could get it, though Father wasn’t keen on that one. I saved the issues that mentioned art and kept them hidden away with my drawing equipment.

The Times – and sometimes the other papers, too – were often critical of my heroes, who were determined to shake up the art world. But the more criticism they received, the more I adored them. They were so thrilling and forward-thinking – everything I wanted my life to be like.

I dreamed of living in London and imagined myself debating what makes good art with Dante Gabriel Rossetti – who was impossibly handsome in the pictures I’d seen – or John Millais – who had a kind, friendly face. I had to admit, I was hazy on the details of where these debates would take place – I had an uneasy feeling the painters I so admired spent a lot of time in taverns – but I knew just spending time with those men would make me feel alive.

‘Why, Miss Hargreaves,’ I imagined Dante or John saying. ‘You are truly a force to be reckoned with.’

It wasn’t just the men I admired. I had read that Elizabeth Siddal, who modelled for the painters and who was rumoured to be in love with Rossetti, had taken up painting herself. Oh, how I longed to be like her. Sometimes when I was feeling particularly vain, I thought I looked a bit like her, because I had long red hair, like hers.

Some people thought red hair was unlucky, but Lizzie made it look beautiful. She didn’t hide it or twist it under her hat like I always had, so I had started wearing my hair loose now, too, when I could. When I was away from Father’s disapproving eye. It got in my way and often irritated me but I thought it was all part of my plan – like venturing out to paint on the beach. After all, if Lizzie Siddal could be a painter, then why couldn’t I, Violet Hargreaves, do the same?

Lost in my dreams of success, I painted swiftly, my brush flying over the paper. I was just painting the background today. I’d already sketched Philips, draped in a sheet that was strategically pinned to create royal robes and wearing a crown I’d found in my old dressing-up box. He was ankle-deep in a tin tray of water. He had been very willing to pose for me. He was so good to me, and though I was happy he was so amiable I did occasionally wonder if he was harbouring feelings for me that were, perhaps, inappropriate. Father would be furious.

Mind you, Father would be furious if he knew what I was doing now, I thought. He grudgingly allowed me to indulge my love of art as long as I was in the house and out of sight. I’d never have dared go out to the beach if he hadn’t gone up to London for the week.

I daubed white paint on the top of the waves I had painted, and stood for a second, gazing at the sea beyond the easel.

‘King Canute turning back the tide?’ a voice said behind me.

I jumped, feeling a scarlet blush rise up my neck to my cheeks. I hadn’t expected to be interrupted, and I was horrified I had attracted anyone’s attention.

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to startle you.’ It was a man, older than me, and handsome with a kind, intelligent face and bright blue eyes. I looked at my feet, not sure what to say. Father’s disapproval of my painting stung, so I had never talked of it outside the house.

‘It’s very good,’ the stranger said. ‘Is this your own work?’

I nodded. I felt the man’s eyes roam over me and I shifted on the sand uncomfortably.

‘It’s interesting that you’re telling a classical story within a real landscape,’ he said.

‘I’m influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.’

The man gazed at my painting and nodded slowly. ‘Of course,’ he said. ‘I can see that.’

I gasped. He could tell? Maybe I was doing something right.

‘I adore them,’ I said, my words falling over each other as I spoke. ‘They’re wonderful. I want to paint detail like they do. The colours, and the form, of nature …’ I stopped, very aware that I was babbling and barely making sense.

But the man tipped his hat to me and smiled. ‘I’m Edwin Forrest,’ he said.

Recovering my composure, I bowed my head slightly. ‘I’m pleased to make your acquaintance, sir,’ I lied, wishing he would leave.

‘Forgive me,’ said Mr Forrest. ‘It is very hot and I’ve been walking a while. Would you mind if I rested here?’ He didn’t wait for my answer, but took his hat off and sat on a large rock a little way from me.

I looked at him in horror. I didn’t want an audience while I painted. And I certainly didn’t want a man – a handsome man – at my shoulder. I was shy and uncomfortable around strangers at the best of times, and unknown men made me very uneasy.

‘Please carry on,’ Mr Forrest said. ‘I’d love to see how you compose your work.’

Feeling self-conscious, but not wanting to argue, I picked up my brush again. I tried to carry on painting the waves, but I couldn’t concentrate knowing Mr Forrest was watching. I felt his eyes on me, hot as sunlight, and my hand shook as I dabbed the paint on the paper.