Полная версия

Полная версияStrange Survivals

I differ from Mr. Greenwell in one point only – that these basins being at a distance from the body may be inconsistent with the explanation he proposes. On the contrary, I conceive that these cup-like hollows were at the circumference of the original mound, and were often replenished with food or drink. As the mound spread through the action of rain, or as other interments were made in it, and it was enlarged, these basins became buried.

The parkin cakes baked in Yorkshire in November, the simnel or soul-mass cakes of Lancashire, the gauffres baked at All Souls-tide in Belgium, are all reminiscences of the food prepared and offered to the dead at All Souls, the great day of commemoration of the departed. Not only did the living eat the cakes, but they were given as well to the dead. In Belgium the idea still holds that the pancakes or gauffres avail the souls; but through a confusion of ideas, the ignorant suppose that the living by eating them satisfy the dead, and as these pancakes are very indigestible, it is customary to hire robust men to gorge themselves on gauffres so as to content the departed ones with a good meal. A has a dear deceased relative B. In order that B may be well supplied with pancake, A ought to eat a plentiful supply; but A shrinks from an attack of indigestion, which a surfeit would bring on, so he hires C to glut himself on gauffres in his room.

The Flemish name for these cakes are “zielen brood” or soul-bread. “At Dixmude and its neighbourhood it is said that for every cake eaten a soul is delivered from purgatory. At Furnes the same belief attaches to the little loaves called ‘radetjes,’ baked in every house. At Ypres the children beg in the street on the eve of All Souls for some sous wherewith ‘to make cakes for the little souls in purgatory.’ At Antwerp these soul-cakes are stained yellow with saffron, to represent the flames of purgatory.”49 In the North of England all idea as to the connection between these cakes and the dead is lost, but the cakes are still made. This custom is a transformation under Christian influence of the still earlier usage of putting food on the graves. When food and drink were furnished to the dead, then necessarily the dead must have their mugs and platters for the reception of their food, and the basins scooped in the soil of a barrow in all likelihood served this purpose.

In like manner there are basins cut on some of the dolmens, and other depressions that were natural were employed for the same purpose. On the coverer of a dolmen close to the railway at Assier, in the Department of Lot, is such a rock basin, natural perhaps, but if natural, then utilised for the purpose of a food or drink vessel for the dead. Another dolmen in the same department, at Laramière, has one distinctly cut by art at the eastern extremity of the covering stone. Inside dolmens and covered avenues stones have been found with cup-like hollows scooped out in them. These served the same purpose, and were in such monuments as were accessible in the interior, as, for instance, those stone basins found in the stone-vaulted tombs on the banks of the Boyne, near Drogheda, with their singular inscribed circles. Whereas such dolmens as could not be entered had the food or drink basins outside them.

“The Three Brothers of Grugith,” a cromlech or dolmen at S. Kévern, in Cornwall, has eight cup-like hollows on the coverer and one in one of the uprights. They vary from 4 to 6 inches in diameter and are 1½ inches deep.

The cup-like holes found so frequently in connection with palæolithic monuments may probably be explained in this way. Originally intended as actual food receptacles or cups for drink, they came in time to be employed as a mere form, and no particular care was taken as to the position they occupied. Thus, very often an upright stone has these cup-marks on it; sometimes they are on the under surface of a covering stone. They belong to the period of the rude stone monuments. With the advent of bronze they gradually disappear. They are not found always associated with interments, though generally so, and it is probable that the stones bearing them which do not at present seem to be intended to mark the place of an interment may have done so originally.

We know that in a great number of cases a mere symbol was taken to serve the purpose of something of actual, material use. Thus, the Chinese draw little coats and hats on paper and burn them, and suppose that by this means they are transmitting actual coats and hats to their ancestors in the world of spirits. In Rome, at certain periods, statuettes were thrown into the Tiber: these were substitutes for the human sacrifices formerly offered to the river. Probably the custom of giving food and drink to the dead gradually died out among the palæolithic men, but that of making the cups for the reception of the gifts remained, and as their purpose was forgotten, the stones graven with the hollows were set up anyhow.

The question has been often raised whether the rock-basins found on granite heights are of artificial origin. It is perhaps too hastily concluded that they are produced by water and gravel rotating in the wind. No doubt a good many have this origin; but I hardly think that all are natural, and it is probable that some have been begun by art and then enlarged by nature, and also that natural basins may have been used by the palæolithic men as drink or food vessels for the gods or spirits in the wind.

About twelve years ago I dug up a menhir that had lain for certainly three centuries under ground, and had served on one side as a wall for the “leat” or conduit of water to the manorial mill. There was no mistaking the character of the stone. It was of fine grained granite, and had been brought from a distance of some eight miles. It was unshaped at the base, and marked exactly how much of it had been sunk in the ground. It stood when re-erected 10 feet 10 inches above the surface. The singular feature in it is this. At the summit, which measures 15 inches by 12 inches, is a small cup 3 inches deep sunk in the stone, 4½ inches in diameter, and distinctly artificial. Now, that the monolith had been standing upright for a vast number of years, was shown by this fact, that the rain water, accumulating in the artificial cup, driven by the prevailing S.W. wind, had worn for itself a lip, and in its flow had cut itself a channel down the side of the stone opposite to the direction of the wind to the distance of 1 foot 6 inches.

What can this cup have been intended for? It is probable that it was a receptacle for rain water, which was to serve for the drink of the dead man above whom the monolith was erected. The Rev. W. C. Lukis, one of the highest authorities on such matters, was with me at the time of the re-erection of this monolith, and it then occurred to him that the holes at the top of so many of the Brittany menhirs, in which now crosses are planted, were not made for the reception of the bases of these crosses, but already existed in the menhirs, and were utilised in Christian times for the erection therein of crosses which sanctified the old heathen monuments. Some upright stones have the cup-hollows cut in their sides, so that nothing could rest in them; but I venture to suggest that these may be symbolic cups, carved after their use, as food and drink receptacles, had been abandoned.

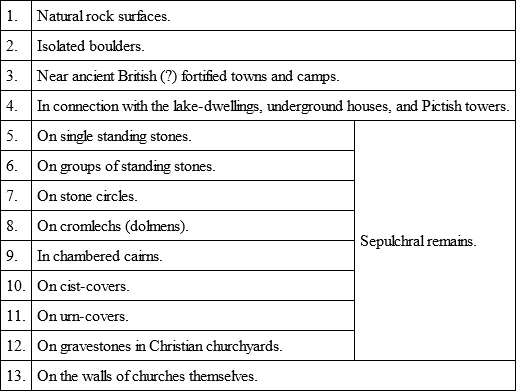

Mr. Romilly Allen, in a paper on some sculptured rocks near Ilkley in Yorkshire,50 that have these cup-hollows, says, “The classes of monuments on which they are found are as follows: —

“From the fact of cup-markings being found in so many instances directly associated with sepulchral remains, I think it may fairly be inferred that they are connected in some way or other with funeral rites, either as sacred emblems or for actual use in holding small offerings or libations.”

Mr. Romilly Allen is, I believe, quite right in his conjecture, which is drawn from observation of the frequency with which these cup-hollows are associated with sepulchral stones. But it must be remembered that a libation is the last form assumed by the usage of giving a drink to either the dead or to a god. The conception of a sacrifice is comparatively modern, the primitive idea in connection with the offering of a liquid is the giving of some acceptable draught to some being who is in the spirit world.

The fact, and it is a fact, that these cup-markings are found on Christian tombstones, shows how the old habit continued to find expression after the meaning which had originated it was completely lost.51

These singular cup-markings are found distributed over Denmark, Norway, Scotland, Ireland, England, France, Switzerland.

All cup-hollows cannot indeed be explained as drink vessels for the dead. Those, for instance, carved in the slate at a steep incline of the cliffs near New Quay in Cornwall, and others in the perpendicular face of the rock also in the same place cannot be so interpreted, but their character is not that altogether of the cup-markings found elsewhere. The hollows are often numerous, and are irregularly distributed. Sometimes they have a channel surrounding a group. That they had some well-understood meaning to the people of the neolithic age who graved them in the rock cannot be doubted. It is said that in places grease and oil are still put into them by the ignorant peasantry as oblation; and this leads to the conclusion that, when first graven, they were intended as receptacles for offerings.

One day, in a graveyard in the west of England, I came on an old stone basin, locally termed a “Lord’s measure,” an ancient holy-water vessel,52 standing under the headstone, above a mound that covered the dust of someone who had been dearly loved. The little basin was full of water, and in the water were flowers.

As I stood musing over this grave, it was not wonderful that my mind should travel back through vast ages, and follow man in his various moods, influenced in his treatment of the dead by various doctrines relative to the condition of the soul.

Here was the cup for holy water, itself a possible descendant of the food-vessel for the dead. And now it is used, not to furnish the dead with drink and meat, but with flowers. And it seemed to me that man was the same in all ages, through all civilisations, and that his acts are governed much more by custom than by reason. Is it not quite as irrational to put flowers on a grave as to put on it cake or ale? Does the soul live in the green mound with the bones? Does it come out to smell and admire the roses and lilies and picotees? The putting flowers on the grave is a matter of sentiment. Quite so – and in a certain phase of man’s growth in culture the food-vessel was cut in stone as a mere matter of sentiment, even when no food was put in it.

There are many of the customs of daily life which deserve to be considered, and which are to us full of interest, or ought to be so, for they tell us such a wondrous story. If I have in this little volume given a few instances, it is with the object of directing attention to the survivals of usage which had its origin in ideas long ago abandoned, and to show how much there is still to be learned from that proper study of mankind – Man.

Archæology is considered a dry pursuit, but it ceases to be dry when we find that it does not belong solely to what is dead and passed, but that it furnishes us with the interpretation of much that is still living and is not understood.

XIII.

Raising the Hat

It is really remarkable how many customs are allowed to pass without the idea occurring as to what is their meaning. There is, for instance, no more common usage of everyday life than that of salutation by raising the hat, or touching the cap, and yet, not one person in ten thousand stops to inquire what it all means – why this little action of the hand should be accepted as a token of respect.

Raising the hat is an intermediate form; the putting up the finger to the cap is the curtailed idea of the primitive act of homage, reduced to its most meagre expression.

There is an amusing passage in Sir Francis Head’s “Bubbles from the Brunnen of Nassau” on hat-lifting:

“At nearly a league from Langen-Schwalbach, I walked up to a little boy who was flying a kite on the top of a hill, in the middle of a field of oat-stubble. I said not a word to the child – scarcely looked at him; but as soon as I got close to him, the little village clod, who had never breathed anything thicker than his own mountain air, actually almost lost string, kite, and all, in an effort, quite irresistible, which he made to bow to me, and take off his hat. Again, in the middle of the forest, I saw the other day three labouring boys laughing together, each of their mouths being, if possible, wider open than the others; however, as they separated, off went their caps, and they really took leave of each other in the very same sort of manner with which I yesterday saw the Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg return a bow to a common postillion.” Then Sir Francis Head goes on to moralise on courtesy, but never for a moment glances at the very curious question, “What is the meaning of this act? What was the original signification of this which is now a piece of formal expression of mutual respect?”

The raising the hat is in act similar to the subscription to a letter, “your humble servant,” the recognition of being in subjection to the person saluted.

To wear a hat, a covering to the head, was a symbol of authority and power. The crown is merely the head-cover originally worn by the sovereign alone. Afterwards to cover the head signified the possession of freedom, and the slave was bare-headed. When, among the Romans, a slave was manumitted, that slave, as badge of his being thenceforth a free man, assumed the Phrygian cap. On numerous monuments, Roman masters exhibited their munificence to their slaves by engraving caps of liberty, each cap signifying a slave who had been set free.

This is the meaning of the Cap of Liberty. On the murder of Caligula, the mob hoisted Phrygian caps on poles, and ran about with them shouting that they were no longer slaves. The death of the tyrant released them from a servile position.

In mediæval Germany, the giving of a hat was a symbolic act, conveying with it feudal tenure. He who received the hat put his hand into it, as a sign that he grasped all those rights which sprang out of the authority conveyed to him by the presentation of the hat. The Pope, when creating a Cardinal, sends him a scarlet hat. The wearing the hat was allowed only to nobles and freemen – no serf might assume one. Among the Goths, the priests as well as the nobles wore the head covered.

When Gessler set a hat on a pole, it was a token that he was exercising sovereign authority. The elevation of a hat on a pole was also a summons of vassals to war, like the raising of a royal standard. In a French Court of Justice, the judges alone wear their heads covered, in token that they are in exercise of authority there. So in our own universities, the tutor or lecturer wears his square cap. So in the cathedral, a bishop was wont to have his head covered with the mitre; and in a parish church, the pastor wore a biretta. We take off our hats when entering church to testify our homage and allegiance to God; and so in old Catholic ritual, the priest and bishop removed their headgear at times, in token that they received their offices from God.

It roused the Romans to anger because the fillet of royalty was offered to Julius Cæsar. This was the merest shred of symbol – yet it meant that he alone had a right to wear a cover on his head; in other words, that all save he were vassals and serfs. That presentation by Mark Antony brought discontent to a head, and provoked the assassination of Cæsar.

Odin, the chief god of Norse mythology, is called Hekluberand, the Hood-bearer; he alone has his head covered. As god of the skies this no doubt refers to the cloud-covering, but it implies also his sovereignty. So Heckla is not only the covered mountain, but the king or chief of the mountains of Iceland.

We can now see exactly what is the meaning of doffing the cap. It implies that the person uncovering his head acknowledges himself to be the serf of the person before whom he uncovers, or at all events as his feudal inferior. How completely this is forgotten may be judged in any walk abroad we take – when we uncover to an ordinary acquaintance – or we can see it in the Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg removing his hat to the postillion. The curtsey, now almost abandoned, is the bowing of the knee in worship; so is the ordinary bend of the body; even the nod of the head is a symbolic recognition of inferiority in the social scale to the person saluted.

The head is the noblest part of man, and when he lifts his hat that covers it, he implies, or rather did imply at one time, that his head was at the disposal of the person to whom he showed this homage.

There is a curious story in an Icelandic saga of the eleventh century in illustration of this. A certain Thorstein the Fair had killed Thorgils, son of an old bonder in Iceland, named also Thorstein, but surnamed “The White,” who was blind. The rule in Iceland was – a life for a life, unless the nearest relative of the fallen man chose to accept blood-money. Five years after the death of Thorgils, Thorstein the Fair came to Iceland and went at once to the house of his namesake, White Thorstein, and offered to pay blood-money for the death of Thorgils, as much as the old man thought just. “No,” answered the blind bonder, “I will not bear my son in my purse.” Thereupon, Fair Thorstein went to the old man and laid his head on his knees, in token that he offered him his life. White Thorstein said, “I will not have your head cut off at the neck. Moreover, it seems to me that the ears are best where they grow. But this I adjudge – that you come here, into my house, with all your possessions, and live with me in the place of my son whom you slew.” And this Fair Thorstein did.

At a period when no deeds were executed in parchment, symbolic acts were gone through, which had the efficacy of a legal deed in the present day.

When Harald Haarfager undertook to subdue the petty kings of Norway, one of these kings, Hrollaug, seeing that he had not the power to withstand Harald, “went to the top of the mound on which the kings were wont to sit, and he had his throne set up thereon and seated himself upon it. Then he had a number of feather beds laid on a bench below, on which the earls were wont to be seated, and he threw himself down from the throne, and rolled on to the earls’ bench, thus giving himself out to have taken on him the title and position of an earl.”53 And King Harald accepted this act as a formal renunciation of his royal title. Every head covering was a badge of nobility, from the Crown to the Cap of Maintenance, through all degrees of coronet. In 1215, Hugh, Bishop of Liège, attended the synod in the Lateran, and first he took his place on the bench wearing a mantle and tunic of scarlet, and a green cap to show he was a count, then he assumed a cap with lappets (?) manicata, to show he was a duke, and lastly put on his mitre and other insignia as a bishop. When Pope Julius II. conferred on Henry VIII. the title of “Defender of the Faith,” he sent him as symbols of authority a sword and a cap of crimson velvet turned up with ermine.

It is probable that originally to uncover the head signified that he who bared his head acknowledged the power and authority of him whom he saluted to deal with his head as he chose. Then it came to signify, in the second place, recognition of feudal superiority. Lastly, it became a simple act of courtesy shown to anyone.

In the same way every man in France is now Monsieur, i. e., my feudal lord; and every man in Germany Mein Herr; and every man in England Mr., i. e., Master. The titles date from feudal times, and originally implied feudal subjection. It does so no longer. So also the title of Esquire implies a right to bear arms. The Squire in the parish was the only man in it who had his shield and crest. The Laird in a Scottish country place is the Lord, the man to whom all looked for their bread. So words and usages change their meaning, and yet are retained by habit, ages after their signification is lost.

THE END1

Sacrifices of the same kind were continued. Livy, xxii. 57: “Interim ex fatalibus libris sacrificia aliquot extraordinaria facta: inter quæ Gallus et Galla, Græcus et Græca, in Foro Boario sub terra vivi demissi sunt in locum saxo conseptum, jam ante hostiis humanis, minime Romano sacro, imbutum.”

2

Jovienus Pontanus, in the fifth Book of his History of his own Times. He died 1503.

3

These cauldrons walled into the sides of the churches are probably the old sacrificial cauldrons of the Teutons and Norse. When heathenism was abandoned, the instrument of the old Pagan rites was planted in the church wall in token of the abolition of heathenism.

4

There is a rare copper-plate, representing the story, published in Cologne in 1604, from a painting that used to be in the church, but which was destroyed in 1783. After her resurrection, Richmod, who was a real person, is said to have borne her husband three sons.

5

Magdeburg, Danzig, Glückstadt, Dünkirchen, Hamburg, Nürnberg, Dresden, etc. (see Petersen: “Die Pferdekópfe auf den Bauerhäusern,” Kiel, 1860).

6

Herodotus, iv. 103: “Enemies whom the Scythians have subdued they treat as follows: each having cut off a head, carries it home with him, then hoisting it on a long pole, he raises it above the roof of his house – and they say that these act as guardians to the household.”

7

The floreated points of metal or stone at the apex of a gable are a reminiscence of the bunch of grain offered to Odin’s horse.

8

Aigla, c. 60. An Icelandic law forbade a vessel coming within sight of the island without first removing its figure-head, lest it should frighten away the guardian spirits of the land. Thattr Thorsteins Uxafots, i.

9

Finnboga saga, c. 34.

10

Hood is Wood or Woden. The Wood-dove in Devon is Hood-dove, and Wood Hill in Yorkshire is Hood Hill.

11

See numerous examples in “The Western Antiquary,” November, 1881.

12

On a discovery of horse-heads in Elsdon Church, by E. C. Robertson, Alnwick, 1882.

13

“Sir Tristram,” by Thomas of Erceldoune, ed. Sir Walter Scott, 1806, p. 153.

14

See an interesting paper and map, by Dr. Prowse, in the Transactions of the Devon Association, 1891.

15

Two types, the earliest, convex on both faces. The later, flat on one side, convex on the other. The earlier type (Chelles) is the same as our Drift implements. Till the two types have been found, the one superposed on the other, we cannot be assured of their sequence.

16

In the artistic faculty. The sketches on bone of the reindeer race were not approached in beauty by any other early race.

17

“The Past and the Present,” by A. Mitchell, M.D., 1880.

18

The author found and planned some hut circles very similar to those found in Cornwall and Down, on a height above Laruns. There was a dolmen at Buzy at the opening of the valley.

19

Hor. Sat. ii. 8.

20

Fornaldar Sögur. iii. p. 387.

21

Heimskringla, i., c. 12.

22

I have given an account of the Carro already in my book, “In Troubadour Land.”

23

Roman and Greek ladies employed parasols to shade their faces from the sun, and to keep off showers. See s. v. Umbraculum in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.