Полная версия

Полная версияThe Half-Back: A Story of School, Football, and Golf

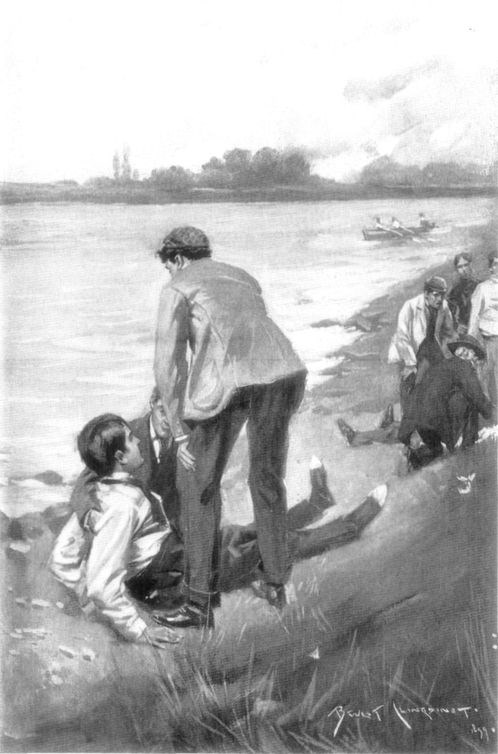

With a frantic leap through the water Joel sped toward it. A bare head followed the upstretched arm; two wild, terror-stricken eyes opened and looked despairingly at the peaceful blue heavens; the white lips moved, but no sound came from them. And then, just as the eyes closed and just as the body began to sink, as slowly as it had arisen, and for the last time, Joel reached it.

There was no time left in which to pause and select a hold of the drowning boy, and Joel caught savagely at his arm and struck toward the bank, and the inert body came to the surface like a water-logged plank.

"Clausen!" shouted Joel. "Clausen! Can you hear? Brace up! Strike out with your right hand, and don't grab me! Do you hear?"

But there was no answer. Clausen was like stone in the water. Joel cast a despairing glance toward the bluff. Then his eyes brightened, for there sliding down the bank he saw a crowd of boys, and as he looked another on the bluff threw down a coil of new rope that shone in the afternoon sunlight as it fell and was seized by some one in the throng below.

Nerved afresh, Joel took a firm grasp on Clausen's elbow and struck out manfully for shore. It was hard going, and when a bare dozen long strokes had been made his burden so dragged him down that he was obliged to stop, and, floundering desperately to keep the white face above water, take a fresh store of breath into his aching lungs. Then drawing the other boy to him so that his weight fell on his back, he brought one limp arm about his shoulder, and holding it there with his left hand started swimming once more. A dozen more strokes were accomplished slowly, painfully, and then, as encouraging shouts came from shore, he felt the body above him stir into life, heard a low cry of terror in his ear, and then–they were sinking together, Clausen and he, struggling there beneath the surface! Clausen had his arm about Joel's neck and was pulling him down–down! And just as his lungs seemed upon the point of bursting the grasp relaxed around his neck, the body began to sink and Joel to rise!

With a deafening noise as of rushing water in his ears, Joel reached, caught a handful of cloth, and struggled, half drowned himself, to the surface. And then some one caught him by the chin–and he knew no more until he awoke as from a bad dream to find himself lying in the sun on the narrow beach, while several faces looked down into his.

"Did you get him?" he asked weakly.

"Yep," answered Outfield West, with something that sounded like a sob in his voice. "He's over there. He's all right. Don't get up," he continued, as Joel tried to move. "Stay where you are. The fellows are bringing a boat, and we'll take you both back in it."

"Stay where you are; The fellows are bringing a boat.

"All right," answered Joel. "But I guess I'll just look around a bit." And he sat up. At a little distance a group among which Joel recognized the broad back of Professor Gibbs were still working over Clausen. But even as he looked Joel was delighted to see Clausen's legs move and hear his weak voice speaking to the professor. Then the boat was rowed in, the occupants panting with their hurried pull from the boathouse, and Joel clambered aboard, disdaining the proffered help of West and others, and Clausen was lifted to a seat in the bow.

On the way up river Joel told how it happened, West throwing in an eager word here and there, and Clausen in a low whisper explaining that the shell had struck on a sunken rock or snag when passing the island, and had begun to sink almost immediately.

"And Cloud?" asked Professor Gibbs. There was no reply from either Joel or Clausen or-West. Only one of the rowers answered coldly:

"He's safe. I saw him on the path near the Society Building. He was running toward Warren." A silence followed. Then–

"You've never learned to swim, Clausen?"

"No, sir."

"But it is the rule that no boy is allowed on the river who can not swim. How is that?"

"I–I said I could, sir."

"Humph! Your lie came near to costing you dear, Clausen."

Then no more was said in the boat until the float was reached, although each occupant was busy with his thoughts. Clausen was helped, pale and shaking, to his room, and West and Joel, accompanied by several of their schoolmates, trotted away to the gymnasium, where Joel was put through an invigorating bath and a subsequent rubbing that left him none the worse for his adventure. The story had to be told over and over to each new group that came in after practice, and finally the two friends escaped to West's room, where they discussed the affair from the view-point of participants.

"When I got back to the bluff with the other fellows you weren't to be seen, Joel," West was saying, "and I thought it was all up with poor old Joel March."

"That's just what I thought a bit later," responded Joel, "when that fellow had me round the neck and was trying to show me the bottom of the river."

"And then, when they brought you in, Whipple and Christie, and you were all white and–and ghastly like, you know"–Outfield West whistled long and expressively–"then I thought you were a goner."

Joel nodded. "And Cloud?" he asked presently.

"Cloud has settled himself," responded West. "When he thought Clausen was drowning he just cut and ran–I mean swam–to shore. The fellows are madder than hornets. As Whipple said, you can't insist on a fellow saving another fellow from drowning, but you can insist on his not running away. They're planning to show Cloud what they think of him, somehow. They wouldn't talk about it while I was around. I wonder why?" Outfield stopped suddenly and frowned perplexedly. "Why, a month or six weeks ago I would have been one of the first they would have asked to help! I'm afraid it's associating with you, Joel. You're corrupting me! Say, didn't I make a mess of it this afternoon? I got about ten yards off the beach and just had to give up and pull back–and pull hard. Blessed if I didn't begin to wonder once if I'd make it! The fact is, Joel, I'm an awful dab at swimming. And I ought to be punched for letting you go out there all alone."

"Nonsense, Out! You couldn't help getting tired, especially if you aren't much of a swimmer. And now you speak of it I remember you saying once that you couldn't–" Joel stopped short and looked at West in wondering amazement. And West grew red and his eyes sought the floor, and for almost a minute there was silence in the room. Then Joel arose and stood over the other lad with shining eyes.

"Out," he muttered huskily, "you're a brick!"

West made no reply, but his feet shuffled nervously on the hearth.

"To think of you starting out there after me! Why, you're the–the hero, Out; not me at all!"

"Oh, shut up!" muttered West.

"I'll not! I'll tell every one in school!" cried Joel. "I'll–"

"If you do, Joel March, I'll thrash you!" cried West.

"You can't!–you can't, Out!" Then he paused and laid a hand affectionately on the other's shoulder as he asked softly:

"And it's really so, Out? You can't–" West shook his head.

"I'm afraid it's so, Joel," he answered apologetically. "You see out in Iowa there isn't much chance for a chap to learn, and–and so before this afternoon, Joel, I never swam a stroke in my life."

CHAPTER XII.

THE PROBATION OF BLAIR

Wallace Clausen's narrow escape from death and Joel's heroic rescue were nine-day wonders in the little world of the academy and village. In every room that night the incident was discussed from A to Z: Clausen's foolhardiness, March's grit and courage, West's coolness, Cloud's cowardice. And next morning at chapel when Joel, fearing to be late, hurried in and down the side aisle to his seat, his appearance was the signal for such an enthusiastic outburst of cheers and acclamations that he stopped, looked about in bewilderment, and then slipped with crimson cheeks into his seat, the very uncomfortable cynosure of all eyes.

Older boys, who were supposed to know, stoutly averred that such a desecration of the sacred solitude of chapel had never before been heard of, and "Peg-Leg," long since recovered from his contact with the bell rope, shook his gray head doubtfully, and joined his feeble tones with the cheers of the others. And then Professor Wheeler made his voice heard, and commanded silence very sternly, yet with a lurking smile, and silence was almost secured when, just as the door was being closed, Outfield West slipped through, smiling, his handsome face flushed from his tear across the yard. And again the applause burst forth, scarcely less great in volume or enthusiasm, and West literally bolted back to the door, found it closed, was met with a grinning shake of the head from Duffy, looked wildly about for an avenue of escape, and finding none, slunk to his seat at Joel's side, while the boys joined laughter at his plight to their cheers for his courage.

"You promised not to tell!" hissed West with blazing cheek.

"I didn't, Out; not a word," whispered Joel.

Many eyes were still turned toward the door, but their owners were doomed to disappointment, for Bartlett Cloud failed to appear at chapel that morning, preferring to accept the penalty of absence rather than face his fellow-pupils assembled there in a body. But he did not escape public degradation; for, although he waited until the last moment to go to breakfast, he found the hall filled, and so passed to his seat amid a storm of hisses that plainly told the contempt in which his schoolmates held him. And then, as though scorning to remain in his presence, the place emptied as though by magic, and he was left with burning cheeks to eat his breakfast in solitude.

Joel and Outfield were publicly thanked and commended by the principal, and every master had a handshake and a kind and earnest word for them. The boys learned that Clausen had taken a severe cold from his immersion in the icy water, and had gone to the infirmary. Thither they went and made inquiry. He would be up in a day or two, said Mrs. Creelman; but they could not see him, since Professor Gibbs had charged that the patient was not to be disturbed. And so, leaving word for him when he should awake, Joel and West took themselves away, relieved at not having to receive any more thanks just then.

But three days later Clausen left the infirmary fully recovered, and Joel came face to face with him on the steps of Academy Building. A number of fellows on their way to recitations stopped and watched the meeting. Clausen colored painfully, appeared to hesitate for a moment, and then went to Joel and held out his hand, which was taken and gripped warmly.

"March, it's hard work thanking a fellow for saving your life, and–I don't know how to do it very well. But I guess you'll understand that–that–Oh, hang it, March! you know what I'd like to say. I'm more grateful than I could tell you–ever. We haven't been friends, but it was my fault, I know, and if you'll let me, I'd like to be–to know you better."

"You're more than welcome, Clausen, for what I did. I'm awfully glad West and I happened to be on hand. But there wasn't anything that you or any fellow couldn't have done just as well, or better, because I came plaguey near making a mess of it. Anyhow, it's well through with. As for being friends, I'll be very glad to be, Clausen. And if you don't mind climbing stairs, and have a chance, come up and see me this evening. Will you?"

"Yes, thanks. Er–well, to-night, then." And Clausen strode off.

After supper West and Clausen came up to Joel's room, and the four boys sat and discussed all the topics known to school. Richard Sproule was at his best, and strove to do his share of the entertaining, succeeding quite beyond Joel's expectations. When the conversation drew around to the subject of the upsetting on the river, Clausen seemed willing enough to tell his own experiences, but became silent when Cloud's name was mentioned.

"I've changed my room, and haven't seen Cloud since to speak to," he said. And so Cloud's name was omitted from discussion.

"I'm sorry," said Clausen, "that I made such a dunce of myself when you were trying to get me out. I don't believe I knew what I was doing. I don't remember it at all."

"I'm sure you didn't," answered Joel. "I guess a fellow just naturally wouldn't, you know. But I was glad when you let go!"

"Yes, you must have been. The fellows all say you were terribly plucky to keep at it the way you did. When they got you it was all they could do to make you let go of me, they say."

"The queerest thing," said West, with a laugh, "was to see Post standing on shore and trying to throw a line to you all. It never came within twenty yards of you, but he kept on shouting: 'Catch hold–catch hold, can't you? Why don't you catch hold, you stupid apes?'"

"And some one told me," said Sproule, "that Whipple took his shoes, sweater, and breeches off, and swam out there with his nose-guard on."

"Used it for a life-preserver," suggested West.–"Did you get lectured, Clausen?"

"Yes, he gave it to me hard; but he's a nice old duffer, after all. Said I had had pretty near punishment enough. But I've got to keep in bounds all term, and can't go on the river again until I learn how to swim."

"Shouldn't think you'd want to," answered Sproule.

"Are you still on probation, March?" asked Clausen.

"Yes, and it doesn't look as though I'd ever get off. If I could find out who cut that rope I'd–I'd–"

"Well, I must be going back," exclaimed Clausen hurriedly. "I wish, March, you'd come and see me some time. My room's 16 Warren. I'm in with a junior by the name of Bowler. Know him?"

Joel didn't know the junior, but promised to call, and West and Clausen said good-night and stumbled down the stairway together.

The next morning Joel dashed out from his history recitation plump into Stephen Remsen, who was on his way to the office.

"Well, March, congratulations! I'm just back from a trip home and was going to look you up this afternoon and shake hands with you. I'll do it now. You're a modest-enough-looking hero, March."

"I don't feel like a hero, either," laughed Joel in an endeavor to change the subject. "I'm just out from Greek history, and if I could tell Mr. Oman what I think–"

"Yes? But tell me, how did you manage–But we'll talk about that some other time. You're feeling all right after the wetting, are you?" And as Joel answered yes, he continued: "Do you think you could go to work again on the team if I could manage to get you off probation?"

"Try me!" cried Joel. "Do you think they'll let up on me?"

"I'm almost certain of it. I'm on my way now to see Professor Wheeler, and I'll ask him about you. I have scarcely any doubt but that, after your conduct the other day, he will consent to reinstate you, March, if I ask him. And I shall be mighty glad to do so. To tell the truth, I'm worried pretty badly about–well, never mind. Never cross a river until you come to it."

"But, Mr. Remsen, sir," said Joel, "do you mean that he will let me play just because–just on account of what happened the other day?"

"On account of that and because your general conduct has been of the best; and also, because they have all along believed you innocent of the charge, March. You know I told you that when Cloud and Clausen were examined each swore that the other had not left the room that evening, and accounted for each other's every moment all that day. But, nevertheless, I am positive that Professor Wheeler took little stock in their testimony. And as for Professor Durkee, why, he pooh-pooed the whole thing. You seem to have made a conquest of Professor Durkee, March."

"He was very kind," answered Joel thoughtfully. "I don't believe, Mr. Remsen, that I want to be let off that way," he went on. "I'm no less guilty of cutting the bell rope than I was before the accident on the river. And until I can prove that I am not guilty, or until they let me off of their own free wills, I'd rather stay on probation. But I'm very much obliged to you, Mr. Remsen."

And to this resolve Joel adhered, despite all Remsen's powers of persuasion. And finally that gentleman continued on his way to the office, looking very worried.

The cause of his worry was known to the whole school two days later when the news was circulated that Wesley Blair was on probation. And great was the consternation. The football game with St. Eustace Academy was fast approaching, and there was no time to train a satisfactory substitute for Blair's position at full-back, even had one been in reach. And Whipple as temporary captain was well enough, but Whipple as captain during the big game was not to be thought of with equanimity. The backs had already been weakened by the loss of Cloud, who, despite his poor showing the first of the season, had it in him to put up a rattling game. And now to lose Blair! What did the faculty mean? Did it want Hillton to lose? But presently hope took the place of despair among the pupils. He was going to coach up and pass a special exam the day before the game. Professor Ludlow was to help him with his modern languages and Remsen with his mathematics, while Digbee, that confirmed old grind, had offered to coach him on Greek. And so it would be all right, said the school; you couldn't down Blair; he'd pass when the time came!

But Remsen–and Blair himself, had the truth been known–were not so hopeful. And Remsen went to West and besought him to induce Joel to allow him (Remsen) to ask for his reinstatement. And this West very readily did, bringing to bear a whole host of arguments which slid off from Joel like water from a duck's back. And Remsen groaned and shook his head, but always presented a smiling, cheerful countenance in public. Those were hard days for the first eleven. Despair and discouragement threatened on all sides, and, as every thoughtful one expected, there was such a slump in the practice as kept Remsen and Whipple and poor Blair awake o' nights during the next week. But Whipple toiled like a Trojan, and Remsen beamed contentment and scattered tongue-lashings alternately; and Blair, ever armed with a text-book, watched from the side-line whenever the chance offered.

Joel seldom went to the field those days. The sight of a canvas-clad player made him ready to weep, and a soaring pigskin sent him wandering away by himself along the river bluff in no enviable state of mind. But one day he did find his way to the gridiron during practice, and he and Blair sat side by side, or raced down the field, even with a runner, and received much consolation in the sort of company that misery loves, and, deep in discussion of the faults and virtues of the players, forgot their troubles.

"Why, it wouldn't have mattered if you were playing, March," said Blair. "For there's no harm in telling you now that we were depending on you for half the punting. Remsen thinks you are fine and so do I. 'With March to take half the punting off your hands,' said he one day, 'you'll have plenty of time to run the team to the Queen's taste.' Why, we had you running on the track there, so you would get your lungs filled out and be able to run with the ball as well as kick it. If you were playing we'd be all right. But as it is, there isn't a player there that can be depended on to punt twenty yards if pushed. Some of 'em can't even catch the ball if they happen to see the line breaking! St. Eustace is eight pounds heavier in the line than we are, and three or four pounds heavier back of it. So what will happen? Why, they'll get the ball and push us right down the field with a lot of measly mass plays, and we won't be able to kick and we won't be able to go through their line. And it's dollars to doughnuts that we won't often get round their ends. It's a hard outlook! Of course, if I can pass–" But there Blair stopped and sighed dolefully. And Joel echoed the sigh.

The last few days before the event of the term came, and found the first eleven in something approaching their old form. Blair continued to burn the midnight oil and consume page after page of Greek and mathematics and German, which, as he confided despondently to Digbee, he promptly forgot the next moment. Remsen made up a certain amount of lost sleep, and Whipple gained the confidence of the team. Joel studied hard, and refound his old interest in lessons, and dreamed nightly of the Goodwin scholarship. West, too, "put in some hard licks," as he phrased it, and found himself climbing slowly up in the class scale. And so the day of the game came round.

The night preceding it two things of interest happened: the eleven and substitutes assembled in the gymnasium and listened to a talk by Remsen, which was designed less for instruction than to take the boys' mind off the morrow's game; and Wesley Blair took his examination in the four neglected studies, and made very hard work of it, and finally crawled off to a sleepless night, leaving the professors to make their decision alone.

And as the chapel bell began to ring on Thanksgiving Day morning, Digbee entered Blair's room, and finding that youth in a deep slumber, sighed, wrote a few words on a sheet of paper, placed this in plain sight upon the table, and tiptoed noiselessly out.

And the message read:

"We failed on the Greek. I'm sorrier than I can tell you.–Digbee."

CHAPTER XIII.

THE GAME WITH ST. EUSTACE

There is a tradition at Hillton, almost as firmly inwrought as that which credits Professor Durkee with wearing a wig, to the effect that Thanksgiving Day is always rainy. To-day proved an exception to the rule. The sun shone quite warmly and scarce a cloud was to be seen. At two o'clock the grand stand was filled, and late arrivals had perforce to find accommodations on the grass along the side-lines. Some fifty lads had accompanied their team from St. Eustace, and the portion of the stand where they sat was blue from top to bottom. But the crimson of Hillton fluttered and waved on either side and dotted the field with little spots of vivid color wherever a Hilltonian youth or ally sat, strolled, or lay.

Yard and village were alike well-nigh deserted; here was the staid professor, the corpulent grocer, the irrepressible small boy, the important-looking senior, the shouting, careless junior, the giggling sister, the smiling mother, the patronizing papa, the crimson-bedecked waitress from the boarding house, the–the–band! Yes, by all means, the band!

There was no chance of overlooking the band. It stood at the upper end of the field and played and played and played. The band never did things by halves. When it played it played; and, as Outfield West affirmed, "it played till the cows came home!"

There were plenty of familiar faces here to-day; Professor Gibbs's, old "Peg-Leg" Duffy's, Professor Durkee's, the village postmaster's, "Old Joe" Pike's, and many, many others. On the ground just outside the rope sat West and a throng of boys from Hampton House. There were Cooke and Cartwright and Somers and Digbee–and yes, Wesley Blair, looking very glum and unhappy. He had donned his football clothes, perhaps from force of habit, and sat there taking little part in the conversation, but studying attentively the blue-clad youths who were warming-up on the gridiron. A very stalwart lot of youngsters, those same youths looked to be, and handled the ball as though to the manner born, and passed and fell and kicked short high punts with discouraging ease and vim.

But one acquaintance at least was missing. Not Bartlett Cloud, for he sat with his sister and mother on the seats; not Clausen, for he sat among the substitutes; not Sproule, since he was present but a moment since. But Joel March was missing. In his room at Masters Hall Joel sat by the table with a Greek history open before him. I fear he was doing but little studying, for now and then he arose from his chair, walked impatiently to the window, from which he could see in the distance the thronged field, bright with life and color, turned impatiently away, sighed, and so returned again to his book. But surely we can not tarry there with Joel when Hillton and St. Eustace are about to meet in gallant if bloodless combat on the campus. Let us leave him to sigh and sulk, and return to the gridiron.

A murmur that rapidly grows to a shout arises from the grand stand, and suddenly every eye is turned up the river path toward the school. They are coming! A little band of canvas-armored knights are trotting toward the campus. The shouting grows in volume, and the band changes its tune to "Hilltonians." Nearer and nearer they come, and then are swinging on to the field, leaping the rope, and throwing aside sweaters and coats. Big Greer is in the lead, good-natured and smiling. Then comes Whipple, then Warren, and the others are in a bunch–Post, Christie, Fenton, Littlefield, Barnard, Turner, Cote, Wills. The St. Eustace contingent gives them a royal welcome, and West and Cooke and Somers and others take their places in front of the seats and lead the cheering.