Полная версия

Полная версияThe Booming of Acre Hill, and Other Reminiscences of Urban and Suburban Life

"She sent her a ball of shaving-paper," Mrs. Carraway said.

A faint smile flitted over Carraway's face. "Well, it might have been worse," he said. "She can use it for curling-paper." He paused a moment. Then he said: "I want to say to you, my dear, that—ah—I want Christmas celebrated this year after my plan of selection. Instead of squandering our hard-earned dollars on things no sensible person wants and none can use, we will consider, first of all, practical utility."

"Very well," sighed Mrs. Carraway. "I quite agree as far as you and I are concerned—but how about the children? I don't think Tommie would feel very happy to wake up on Christmas morning and find a pair of suspenders and a new suit of clothes under the tree. He needs both, but he wants tin soldiers. And as for Mollie, she expects a doll."

"Well, I don't wish to be hard on the children," said Mr. Carraway, "but now is the time to begin training them. There may be a temporary disappointment, but in the end they will be happier for it. Of course I don't say to give them necessities of life for Christmas, but in selecting what we do give them, get something useful. Dolls and tin soldiers and toy balloons are well enough in their way, but they are absolutely useless. Therefore, I say, don't give them such things. Surely Mollie would be pleased to receive a nice little fur tippet or a muff, and I'll get Tommie a handsome snow-shovel, that he can use when he cleans off the paths. He won't mind; it will be a gift worth having, and by degrees he'll come to see that the plan of utility is a good one."

Mrs. Carraway discreetly held her tongue, although she was far from approving Carraway's course in so far as it affected the children. She tacitly agreed to the proposition, but there was the light of an idea in her eye.

The days intervening before Christmas passed rapidly away, and Christmas eve finally came. Tommie and Mollie were bubbling over with suppressed excitement, and frequently went off into spasms of giggles. There was something very funny in the wind evidently. After dinner the small family repaired to the library, where the children were in the habit of distributing their gifts for their parents on the night before Christmas. Mrs. Carraway was beaming, and so was Mr. Carraway. The children had been informed of what they were to expect, and after an hour or two of regret, they had put their little heads together, giggled a half-dozen times, and accepted the situation.

"Your mother has presented me with a ton of coal, children," said Carraway, smiling happily. "Now you may think that a funny sort of gift—"

"Yeth, papa," said Mollie.

"Awful funny," said Tommie, wiggling with glee.

"Well, it does seem so at first, but, now, how much better to give me that than to present me with something that I could look at for a few days and then would have no further use for!"

"That's so, pa," said Mollie.

"I guess you're right," said Tommie. "Wat cher got for ma?"

"I have given her a brand-new set of china for the dining-room," said Mr. Carraway.

"And it was just what I needed," said Mrs. Carraway, happily. "And now, children, go up-stairs, and bring down your presents for your father."

The children sped noisily out of the room and up the stairs.

"I hope you impressed it on their minds that I wanted nothing useless?" said Carraway.

"I did," said Mrs. Carraway. "I explained the whole thing to them, and told them what they might expect to receive. Then I gave them each ten dollars of the money they'd saved, and let them go shopping on their own account. I don't know what they bought you, but it's something huge."

Mrs. Carraway had hardly finished when the two giggling tots came into the room, carrying with difficulty a parcel, which, as Mrs. Carraway had said, was indeed huge. Mr. Carraway eyed it with curiosity as the string was unfastened and the package burst open.

"There," cried Tommie, breathlessly.

"It's all for you, pa, from Mollie and me."

The two children stood to one side. Mrs. Carraway appeared surprised in an amused fashion, while Carraway stood appalled at what lay before him, as well he might; for the package contained a great wax doll with deep staring blue eyes, a small doll's house with two floors in it and a front door that opened, china and chairs and table and bureaus in miniature to furnish the house—indeed, all the paraphernalia of a well-ordered residence for a French doll. Besides these were two boxes of tin soldiers, cannon, tents, swords, a fully equipped lead army, a mechanical fish, and a small zinc steamboat, suitable for a cruise in a bath-tub.

Carraway looked at the children, and the children looked at Carraway.

"Why," said he, as soon as he could recover his equanimity, "there must be some mistake."

"No," said Mollie. "We picked 'em out for you ourselves. We thought you'd need 'em."

Mrs. Carraway turned away to cough slightly.

"Need them?" demanded Carraway with a perplexed frown. "When?"

"Oh—to-morrow," said Tommie.

"What for?" demanded Carraway.

"Why, to give to us, of course" said the children in chorus.

"My dear," said Carraway, two hours later, after the children had retired, "I've been thinking this thing over."

"Yes?" said Mrs. Carraway.

"Yes," said Carraway; "and I've made up my mind that those children of ours are born geniuses. I don't believe, after all, they could have selected anything which would be more satisfactorily useful in the present emergency."

"Well," observed Mrs. Carraway, quietly, "I don't either. I thought so at the time when they asked my permission to do their shopping at the International Toy Bazar."

"It's a solar-plexus retort, just the same," said Carraway, as he shook his head and went to bed. "I think on the 1st of January, if you have no objections, Mrs. Carraway, I will forswear utilitarianism—and you may remove the golf-balls from the cloisonné vase as soon as you choose."

THE BOOK SALES OF MR. PETERS

Like many another town which frankly confesses itself to be a "city of the third class," Dumfries Corners is not only well provided but somewhat overburdened with impecunious institutions of a public and semi-public nature. The large generosity of persons who never give to, but are often identified with, churches, hospitals, associations of philanthropic intent of one kind and another, in Dumfries Corners as elsewhere, is frequently the cause of embarrassment to persons who do give without being lavish of the so-called influence of their names. There are quite a dozen individuals out of the forty thousand souls who live in that favored town who find it convenient to give away as much as five hundred dollars annually for the maintenance of milk dispensaries, hospitals, and other deserving enterprises of similar nature for the needy. Yet at the close of each fiscal year those who have given to this extent are invariably confronted by "reports," issued by officials of the various institutions, frankly confessing failure to make both ends meet, and everybody wonders why more interest has not been taken. "Surely, we have loaned our names!" they say. It never occurs to anybody that one successful charity is better than six failures. It has never entered into the minds of the managers of these enterprises that a man disposed to give away five hundred dollars could make his contributions to the public welfare more efficacious by giving the whole to one institution instead of dividing it among twenty.

However, human nature is the same everywhere, and until the crack of doom sounds mankind will be found undertaking more charity than it can carry through successfully, not only in Dumfries Corners, but everywhere else. It would be difficult to fix the responsibility for this state of affairs, although the large generosity of those who lend their names and blockade their pockets may consider itself a candidate for chief honors in this somewhat vital matter. It may be, too, that the large generosity of people who really are largely generous with their thousands has something to do with it. There is more than one ten-thousand-dollar town in existence which has accepted a hundred-thousand-dollar hospital from generously disposed citizens, and the other citizens thereof have properly hailed their benefactor's name with loud acclaim, but the hundred-thousand-dollar hospital, which might have been a fifty-thousand-dollar hospital, with an endowment of fifty thousand more to make it self-supporting, has a tendency to ruin other charities quite as worthy, because its maintenance pumps dry the pockets of those who have to give. It will require a drastic course of training, I fear, to open the eyes of the public to the fact that even generosity can be overdone, and I must disclaim any desire to superintend the process of securing their awakening, for it is an ungrateful task to criticise even a mistakenly generous person; and man being by nature prone to thoughtless judgments, the critic of a philanthropist who spends a million of dollars to provide tortoise-shell combs for bald beggars would shortly find himself in hot water. Therefore let us discuss not the causes, but some of the results of the system which has placed upon suburban shoulders such seemingly hopeless philanthropic burdens. At Dumfries Corners the book sales of Mr. Peters, one of the vestrymen, were one of these results.

There were two of these sales. The first, like all book sales for charity, consisted largely of the vending of ice-cream and cake. The second was different; but I shall not deal with that until I have described the first.

This had been given at Mr. Peters's house, with the cheerful consent of Mrs. Peters. The object was to raise seventy-five dollars, the sum needed to repair the roof of Mr. Peters's church. In ordinary times the congregation could have advanced the seventy-five dollars necessary to keep the rain from trickling through the roof and leaking in a steady stream upon the pew of Mrs. Bumpkin, a lady too useful in knitting sweaters for the heathen in South Africa to be ignored. But in that year of grace,

1897, there had been so many demands made upon everybody, from the Saint William's Hospital for Trolley Victims, from the Mistletoe Inn, a club for workingmen which was in its initial stages and most worthily appealed to the public purse, and for the University Extension Society, whose ten-cent lectures were attended by the swellest people in Dumfries Corners and their daughters—and so on—that the collections of Saint George's had necessarily fallen off to such an extent that plumbers' bills were almost as much of a burden to the rector as the needs of missionaries in Borneo for dress-suits and golf-clubs. In this emergency, Mr. Peters, whose account at his bank had been overdrawn by his check which had paid for painting the Sunday-school room pink in order that the young religious idea might be taught to shoot under more roseate circumstances than the blue walls would permit, and so could not well offer to have the roof repaired at his own expense, suggested a book sale.

"We can get a lot of books on sale from publishers," he said, "and I haven't any doubt that Mrs. Peters will be glad to have the affair at our house. We can surely raise seventy-five dollars in this way. Besides, it will draw the ladies in the congregation together."

The offer was accepted. Mrs. Peters acquiesced. Peters and his co-workers asked favors and got them from friends in the publishing world. The day came. The books arrived, and the net results to the Roofing Fund of Saint George's were gratifying. The vestry had asked for seventy-five dollars, and the sale actually cleared eighty-three! To be sure, Mr. Wiggins spent fifty dollars at the sale. And Mrs. Thompson spent forty-nine. And the cake-table took in thirty-eight. And the ice-cream was sold, thanks to the voracity of the children, for nineteen dollars. And some pictures which had been donated by Mrs. Bumpkin sold for thirty-one dollars, and the gambling cakes, with rings and gold dollars in them, cleared fifteen. Still, when it was all reckoned up, eighty-three dollars stood to the credit of the roof! In affairs of this kind, results, not expenses, are considered.

Surely the venture was a success. Although from the point of view of bringing the ladies of the congregation together—well, the less said about that the better. In any event, parts of Dumfries Corners were cooler the following summer than they had ever been before.

And then, in the natural sequence of events, the next year came. The hospital, and the inn, and the various other institutions of the city indorsed by prominent names, but void of resources, as usual, left the church so poor that something had to be done to repair the cellar of Saint George's by outside effort, water leaking in from the street. The matter was discussed, and the amount needed was settled upon. This time Saint George's needed ninety dollars. It didn't really need so much, but it was thought well to ask for more than was needed, "because then, you know, you're more likely to get it."

The book-cake-and-cream sale of the year before had been so successful that everybody said: "By all means let us have another literary afternoon at Mr. Peters's."

"All right!" said Peters, calmly, when the project was suggested. "Certainly! Of course! Have anything you please at my house. Not that I am running a casino, but that I really enjoy turning my house inside out in a good cause once in a while," he added, with a smile which those about him believed to be sincere. "Only," said he, "kindly make me master of ceremonies on this occasion."

"Certainly!" replied the vestry. "If this thing is to be in your house you ought to have everything to say about it."

"I ask for control," said Peters, "not because I am fond of power, but because experience has taught me that somebody should control affairs of this sort."

"Certainly," was the reply again, and Peters was made a committee of one, with power to run the sale in his own way, and the vestry settled down in that calm and contented frame of mind which goes with the consciousness of solvency.

Three months elapsed, and nothing was done. No cards were issued from the home of Peters announcing a sale of any kind, cake, cream, or books, and the literary afternoon seemed to have sunk into oblivion. The chairman of the Committee on Supplies, however, having gone into the cellar one morning to inspect the coal reserve, found himself obliged either to wade knee deep in water or to neglect his duty—and, of course, being a sensible man, he chose the latter course. He knew that in impecunious churches willing candidates for vestry honors were rare, and he, therefore, properly saved himself for future use. Wading in water might have brought on pneumonia, and he was aware that there really isn't any reason why a man should die for a cause if there is a reasonable excuse for his living in the same behalf. But he went home angry.

"That cellar isn't repaired yet," he said to his wife. "You'd think from the quantity of water there that ours was a Baptist church instead of the Church of England."

"It's a shame!" ejaculated his wife, who, having that morning finished embroidering a centre-piece for the dinner-table of the missionaries in Madagascar, was full of conscious rectitude. "A perfect shame; who's to blame, dear?"

"Peters," replied the chairman. "Same old story. He makes all sorts of promises, and never carries 'em out. He thinks that just because he pays a few bills we haven't anything to say. But he'll find out his mistake. I'll call him down. I'll write him a letter he won't forget in a hurry. If he wasn't willing to attend to the matter he had no business to accept the responsibility. I'll write and tell him so."

And then, the righteous wrath of the chairman of the Committee on Supplies having expended itself in this explosion at his own dinner-table, that good gentleman forgot all about it, did not write the letter, and in fact never thought of the matter again until the next meeting of the vestry, when he suavely and jokingly inquired if the Committee on Leaks and Book Sales had any report to make. To his surprise Mr. Peters responded at once.

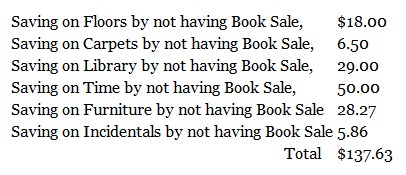

"Yes, gentlemen," he said, taking a check out of his pocket and handing it to the treasurer. "The Committee on Leaks, Literature, and Lemonade reports that the leak is still in excellent condition and is progressing daily, while the Literature and Lemonade have produced the very gratifying sum of one hundred and thirty-seven dollars and sixty-three cents, a check for which I have just handed the treasurer."

Even the rector looked surprised.

"Pretty good result, eh?" said Peters. "You ask for ninety dollars and get one hundred and thirty-seven dollars and sixty-three cents. You can spend a hundred dollars now on the leak and make a perfect leak of it, and have a balance of thirty-seven dollars and sixty-three cents to buy books for the Hottentots or to invest in picture-books for the Blind Asylum library."

"Ah—Mr. Peters," said the chairman of the Committee on Supplies, "I—ah—I was not aware that you'd had the sale. I—ah—I didn't receive any notice."

"Oh yes—we had it," said Peters, rubbing his hands together buoyantly. "We had it last night, and it went off superbly."

"I am sorry," said the chairman of the Committee on Supplies. "I should like to have been there."

"I didn't know of it myself, Mr. Peters," said the rector, "but I am glad it was so successful. Were there many present?"

"Well—no," said Peters. "Not many. Fact is, Mrs. Peters and the treasurer here and I were the only persons present, gentlemen. But the results sought were more than accomplished."

"I don't see exactly how, unless we are to regard this check as a gift," observed the chairman of the Committee on Supplies, coldly.

"Well, I'll tell you how," said Peters. "The check isn't a gift at all. Last year you had a book sale at my house, and this year you voted to have another. I couldn't very well object—didn't want to, in fact. Very glad to have it as long as I was allowed to control it. But last year we cleared up a bare eighty dollars. This year we have cleared up one hundred and thirty-seven dollars and sixty-three cents. Last year's book sale cost me one hundred and twenty-five dollars. The children who attended, aided and abetted by my own, spilled so much ice cream on my dining-room rug that Mrs. Peters was forced to send it to the cleaners. A very charming young woman whose name I shall not mention placed a chocolate eclair upon my library sofa while she inspected a volume of Gibson's drawings. Another equally charming young woman sat down upon it, and, whatever it did to her dress, that eclair effectually ruined the covering of my sofa. Then, as you may remember, the sale of books took place in my library, and I had the pleasure of seeing, too late, one of our sweetest little saleswomen replenishing her stock from my shelves. She had sold out all the books that had been provided, and in a mad moment of enthusiasm for the cause parted with a volume I had secured after much difficulty in London to complete a set of some rarity for about seven dollars less than the book had cost."

"Why did you not object?" demanded the chairman of the Committee on Supplies.

"My dear sir," said Mr. Peters, "I never object to anything my guests may do, particularly if they are charming and enthusiastic young women engaged in church work. But I learned a lesson, and last night's book sale was the result. If the chairman of the Committee on Supplies demands it, here is a full account of receipts."

Mr. Peters handed over a memorandum which read as follows:

"With this statement, gentlemen," said Mr. Peters, suavely, "should the Finance Committee require it, I am prepared to submit the vouchers which show how much wear and tear on a house is required to raise eighty dollars for the heathen."

"That," said the chairman of the Finance Committee, "will not be necessary—though—" and he added this wholly jocularly, "though I don't think Mr. Peters should have charged for his time; fifty dollars is a good deal of money."

"He didn't charge for his time," murmured the treasurer. "In this statement he has paid for it!"

"Still," said he of Supplies, "the social end of it has been wiped out."

"Of course it has," retorted Mr. Peters. "And a very good thing it has been, too. Did you ever know of a church function that did not arouse animosities among the women, Mr. Squills?"

The gentleman, in the presence of men of truth, had to admit that he never knew of such a thing.

"Then what's the matter with my book sale?" demanded Peters. "It has raised more money than last year; has cost me no more—and there won't be any social volcanoes for the vestry to sit over during the coming year."

A dead silence came over all.

"I move," said Mr. Jones, at whose house the meeting was held, "that we go into executive session. Mrs. Jones has provided some cold birds, and a—ah—salad."

Mr. Jones's motion was carried, and before the meeting finally adjourned under the genial influence of good-fellowship and pleasant converse Mr. Peters's second book sale was voted to have been of the best quality.

THE VALOR OF BRINLEY

However differentiated from other suburban places Dumfries Corners may be in most instances, in the matter of obtaining and retaining efficient domestics the citizens of that charming town find it much like all other communities of its class. Civilization brings with it everywhere, it would seem, problems difficult of solution, and conspicuous among them may be mentioned the servant problem. It is probable that the only really happy young couple that ever escaped the annoyance of this particular evil were Adam and Eve, and as one recalls their case it was the interference of a third party, in the matter of their diet, that brought all their troubles upon them, so that even they may not be said to have enjoyed complete immunity from domestic trials. What quality it is in human nature that leads a competent housemaid or a truly-talented culinary artist to abhor the country-side, and to prefer the dark, cellar-like kitchens of the city houses it is difficult to surmise; why the suburban housekeeper finds her choice limited every autumn to the maid that the city folks have chosen to reject is not clear. That these are the conditions which confront surburban residents only the exceptionally favored rustic can deny.

In Dumfries Corners, even were there no rich red upon the trees, no calendar upon the walls, no invigorating tonic in the air to indicate the season, all would know when autumn had arrived by the anxious, hunted look upon the faces of the good women of that place as they ride on the trains to and from the intelligence offices of the city looking for additions to their ménage. Of course in Dumfries Corners, as elsewhere, it is possible to employ home talent, but to do this requires larger means than most suburbanites possess, for the very simple reason that the home talent is always plentifully endowed with dependents. These latter, to the number of eight or ten—which observation would lead one to believe is the average of the successful local cook, for instance—increase materially the butcher's and grocer's bills, and, one not infrequently suspects, the coal man's as well.

Years ago, when he was young and inexperienced, the writer of this narrative, his suspicions having been aroused by the seeming social popularity of his cook, took occasion one Sunday afternoon to count the number of mysterious packages, of about a pound in weight each, which set forth from his kitchen and were carried along his walk in various stages of ineffectual concealment by the lady's visitors. The result was by no means appalling, seven being the total. But granting that seven was a fair estimate of the whole week's output, and that the stream flowed on Sundays only, and not steadily through the other six days, the annual output, on a basis of fifty weeks—giving the cook's generosity a two weeks' vacation—three hundred and fifty pounds of something were diverted from his pantry into channels for which they were not originally designed, and on a valuation of twenty-five cents apiece his minimum contribution to his cook's dependents became thereby very nearly one hundred dollars. Add to this the probable gifts to similarly fortunate relatives of a competent local waitress, of an equally generously disposed laundress with cousins, not to mention the genial, open-handed generosity of a hired man in the matter of kindling-wood and edibles, and living becomes expensive with local talent to help.