скачать книгу бесплатно

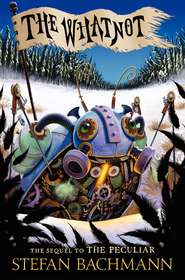

The Whatnot

Stefan Bachmann

The thrilling sequel to Stefan Bachmann’s steampunk faery fantasy THE PECULIAR. This is JONATHAN STRANGE AND MR NORRELL for kids, mixed with a dash of THE BARTIMAEUS TRILOGY…Bartholomew Kettle couldn’t save his sister. He watched her be pushed through the door between worlds, into the icy forest of faery. He saw her take someone’s hand. And he promised that he would find her. But what if he can’t? And what if the sinister forces who were hunting them both haven’t given up, but are just biding their time?Stefan Bachmann spins a consuming tale of magic, of good and evil, of family, and of figuring out where you belong.

To my family, who made me who I am

CONTENTS

Cover (#u1866f1ec-718a-5ea8-aaac-362eec9d623a)

Title Page (#u2004889c-5ed6-5f65-b9d3-b122e7619597)

Dedication (#u31fc4b6a-b42b-57ad-817c-061286e9ce4c)

Prologue (#ua183da87-1516-5cce-b0fe-2233581ff43c)

CHAPTER I: Snatchers (#u2b065049-abfd-539d-9c42-552378b4f95d)

CHAPTER II: Hettie in the Land of Night (#u9d100b92-4e67-5694-a42a-edc4604ff64a)

CHAPTER III: The Sylph’s Gift (#uc4a613b9-832b-51d6-a2c6-c498bc029a74)

CHAPTER IV: The Merry Company (#u1da1783a-6fb9-54e1-a2f7-d4967faa4b6f)

CHAPTER V: Mr. Millipede and the Faery (#u93326c14-c53d-5de6-a593-95df23d2ed24)

CHAPTER VI: The Belusites (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER VII: The Birds (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER VIII: The Insurgent’s House (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER IX: The Pale Boy (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER X: The Hour of Melancholy (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XI: The Scarborough Faery Prison (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XII: The Masquerade (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XIII: The Ghosts of Siltpool (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XIV: The Fourth Face (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XV: Tar Hill (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XVI: A Shade of Envy (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XVII: Puppets and Circus Masters (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XVIII: The City of Black Laughter (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XIX: Pikey in the Land of Night (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XX: Lies (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXI: Truths (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Have you read …? (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_c1561c70-47a1-52c5-8a68-82a63b0877bd)

O one noticed the soldier. He stood in the middle of the ballroom, dark and hunched against the blazing lights, and no one saw. Brightly colored frocks whirled around him. Coattails spun past. The laughter and the chatter filled the air, and the clockwork maids sped right up to him with their heavy trays of glasses and red currant tarts, but he never moved. His face was white as bone. Blue shadows stood out under his eyes, and his uniform was blotted with mud.

Mr. Jelliby did not notice him either, not at first. He was busy being worried and a little bit irritated, leaning against the fireplace and watching the guests as they moved toward the dancing floor. The gentlemen were in full uniform, jangling with swords and medals of bravery, though most had not seen a day of battle. Red sashes slashed down their chests. The ladies smiled and whispered. Such bright birds, Mr. Jelliby thought. So happy. For tonight.

It was hot in the ballroom. The great windows were edged with ice, but inside it was a furnace. Candles were lit, the fire stoked, and the chandeliers burned so bright that the air around them rippled and the ceiling was heavy with smoke. Mr. Jelliby rubbed the hair above his ear, as if to scratch away the silver that was appearing there. He could smell the red currant tarts as they skimmed past. He could smell oil from the servants’ joints, and the damp wraps and overshoes lying in steaming heaps in the neighboring room. The orchestra was tuning up. Dear Ophelia was stooped over a sofa, trying to placate Lady Halifax, who seemed in constant peril of exploding. Mr. Jelliby felt he needed to sit down. He turned away from the mantel, looking for the most convenient escape. …

That was when he spotted the soldier.

Good heavens. Mr. Jelliby squinted. What were things coming to that you could get into a lord’s house dressed like that? The lad’s coat was filthy. The wool was sodden, the buttons dull, and the collar was black with who-knew-what. Had he been fresh off the battlefields it might have made some sense to Mr. Jelliby, but the Wyndhammer Ball was the going-off celebration. The war had not even started yet.

“Dashing good bash, this,” Lord Gristlewood said, sidling up to Mr. Jelliby and interrupting his thoughts. Mr. Jelliby jumped a little. Drat.

Lord Gristlewood was a droopy, fleshy man with pale, swollen hands that made Mr. Jelliby think of dead things soaking in jars of chemicals. Worse yet, Lord Gristlewood was the sort of man who thought everyone liked him even though no one actually did.

“Dashing good,” Mr. Jelliby said. He scanned the crowd, making a point to ignore the other man.

Lord Gristlewood did not take the hint. “Ah, would you look at them. … Brave lads, every one. The pride of England. Why, a thousand bellowing trolls could not frighten these men.”

Mr. Jelliby pressed his lips together.

“Well, don’t you think?” Lord Gristlewood asked.

“No, I don’t usually.” Mr. Jelliby spoke quietly, into his glass, hoping Lord Gristlewood wouldn’t hear.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Oh—That is—I certainly hope so!”

Lord Gristlewood smiled. “Of course you do! Cheer up, old chap. It’s a celebration, after all.”

“Indeed.” Mr. Jelliby set his glass down sharply on the mantel. “Well, old chap, if I’m to be honest with you, I see no reason to celebrate. We are entering into a civil war.”

Lord Gristlewood’s smile slipped a little bit.

Mr. Jelliby didn’t stop. “Tomorrow all you’ll hear is, ‘Hand in your wife’s jewels!’ and ‘Enlist your footman!’ and ‘All for the good of the empire!’ and other such bunk. And then the bodies will start coming back in sacks and wagons, and one will be your footman, and no one will be dancing then. It’s not a funny thing, fighting faeries.”

“Oh, but you are gloomful,” Lord Gristlewood said. “Come now. It’ll never go so far. The faeries are wild! They are leaderless and unorganized, and we shall settle them the way we settled the French. With our superior intellect. Let them come, I say. Let them strike us with all they’ve got. We won’t fall.” Lord Gristlewood gave an uneasy laugh and slid away, apparently deciding to grace a less depressing person with his presence.

Mr. Jelliby sighed. He picked up his glass again, turning it slowly. He took a sip. Over the glinting rim he saw the soldier, standing dark and solitary among the dancers.

Mr. Jelliby watched him a second. Then he smiled. Of course. The boy is shy! Why had he not thought of it before? No doubt the young soldier was frightened out of his wits and wondering how best to ask one of the ladies for a dance. Mr. Jelliby decided to go and rescue him. There was bound to be some equally unhappy nobleman’s daughter about, ideally lacking a sense of smell.

Mr. Jelliby pushed off into the crowd, setting course for the dancing floor at the center of the room. It was like navigating a sea of cotton candy, pressing between all those frocks. More and more couples were moving toward the dancing. In fact, the room seemed to be getting fuller by the second, not with people exactly, but with heat and laughter. Mr. Jelliby’s head began to buzz.

He had not gone ten steps when Lady Maribeth Skimpshaw—who moved within her very own atmosphere of rosy perfume—intercepted him, grabbing his arm and smiling. She had a very pink, gummy smile of the sort that comes with false teeth. Mr. Jelliby had heard she’d had her beginnings in London’s theater district, so doubtless all her real teeth had been traded for poppy potions and illegal faery droughts.

“Lord Jelliby! How perfectly delightful that I’ve found you. Your wife’s arm is going to fall off. She should stop fanning that odious Lady Halifax. The fool thinks someone’s stolen one of her gems, but she probably just forgot how many she put on this evening. No matter. I’ve kidnapped you and that’s what is important.” Her smile stretched. “Now. I know you are terribly busy managing your estates and counting your money and all that, but I absolutely must speak to you very urgently.”

“Oh dear, I hope not.”

“What?”

“I hope Ophelia’s arm doesn’t fall off. Shall I get you a tart?”

“No, Lord Jelliby, are you listening to me?” Her fingers tightened around his arm. “It’s about young Master Skimpshaw. I want to ask you a favor for him.”

Oh, drat again. People were always asking favors of Mr. Jelliby now that he was a lord. They asked for positions in government, or good words slipped to admirals, or whether he had any nonmechanical servants to spare. It drove him to distraction. Just because he had saved London from utter destruction and the Queen had given him a house and some stony fields in a distant corner of Lancashire did not mean he wanted to spend the rest of his life being charitable to aristocrats. Anyway, one would think they could handle their own problems.

“Terribly sorry, my lady, but you will have to find me later. Someone is in need of my assistance now, and”—Mr. Jelliby broke free of Maribeth Skimpshaw’s clutches—“and I really must be going.” He set off again toward the young soldier, trailing rose scent in ribbons behind him.

The orchestra was in full tilt now, sweeping everyone up in a glorious, whirling waltz. Mr. Jelliby could hardly see the soldier anymore. Only snatches of him, in between the spinning figures and bright gowns. His face was chalky. Drained, almost.

“Lord Jelliby? Oh, Arthur Jelliby!” someone called from across the room.

Mr. Jelliby walked faster.

And then, all at once, a rustle passed through the crowd, a disturbance, like the wind in the treetops before a storm. It started on the dancing floor and spread out until it had reached the farthest corners of the ballroom. The rustle swelled. Shouts, then a shriek, and then people were peeling away from Mr. Jelliby, backing up against the walls.

Mr. Jelliby stopped in his tracks.

The young soldier stood directly in front of him, not five paces away. He was alone, all alone on the polished floorboards. His hand was raised, stretched out in front of him. In it was clutched a bloody rag.

Mr. Jelliby let out a little cough.

The rag was blue, the color of England, the color of her army. Shreds of a red sash still clung to it. A spattered medal. The young soldier’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. He simply stared at the rag in his hand, a look of mild surprise on his white, white face.

The ballroom had gone deathly still. No one spoke. No one moved. The clockwork maids had all creaked to a halt. The old ladies were staring so hard their eyes seemed about to pop from their heads. Lady Halifax lay sprawled over a fainting couch, face red as an apple.

Mr. Jelliby’s first thought was, Good heavens, he’s killed someone, but he couldn’t see anyone hurt. No one seemed to be missing a piece of his uniform, nor were there any wounds visible among the swaths of lace and satin.

“Young man,” Mr. Jelliby started to say, unsteadily, taking a step toward the soldier. “Young man, what in—”

But he didn’t have time to say anything else, because suddenly the soldier began to change. As Mr. Jelliby watched, blood came up between the soldier’s teeth and gushed down his chin in a crimson sheet. Bright holes tore themselves through the fabric of his uniform. He spasmed, once, twice, as if being hit by some great, invisible force.

And then he began to fall, so slowly. Petals of black pulled away from his coat, his arms, and the side of his face as he descended through the air. There was a sound like distant guns. And before he struck the floor, he seemed to disintegrate, turn to ash and smoke and black powder.

Then he was gone, and the ladies were screaming.

Mr. Jelliby heard glass breaking. The lights were so hot now, so raging hot. He couldn’t smell the tarts anymore. Only the fear, thick as river mud in the rippling air.

(#ulink_9b5ced28-4ba8-5a42-9d6d-2fa7d98d3a96)

IKEY Thomas dreamed of plums and caramel apples the night the faery-with-the-peeling-face stole his left eye.

It was a wonderful dream. He wasn’t in the bitter chill of his hole under the chemist’s shop anymore. The old wooden signboard with its painted hands and hawthorn leaves no longer creaked overhead, and the ice wasn’t crusting his face. In his sleep Pikey was warm, curled up by an iron stove, and the plums were drifting out of the dark, and he was eating a caramel apple that never seemed to get any smaller.

He always dreamed of caramel apples when he could help it. And iron stoves, too, in the winter. And plums and pies and loud, happy voices calling his name.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap. Far, far away on the other side of his eyelids, a figure entered the frozen alley.

Pikey bit down on his apple. He heard the footsteps, but he tried not to worry. Whoever it was would be gone soon. Folk were always stumbling into the chemist’s alley from Bell Lane, from the gutters and sluiceways and all the other fissures between the old houses of Spitalfields. None of them ever stayed for long.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.

Pikey squirmed inside his blankets. Go away, he thought. Don’t wake me up. But the footsteps kept coming, limping slowly across the cobbles.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.Pikey didn’t feel warm anymore. The plums still fell, but they stung now as they touched his skin, spitting, icy cold. He tried to take another bite of his apple. It turned to wind and cinders, and blew away.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.

Snow was falling. Not plums. Snow. It gusted into his little hole, and suddenly Pikey’s nose was filled with the stench of old water and deep and mossy wells. A racket kicked up, old Rinshi straining against her chain, barking at something and then stopping, sharp-like. There was a grating, a scrape of metal.

Pikey saw the blood before he saw the figure, always the blood trickling toward him between the stones. Then the alley was filled with screams.

Pikey Thomas was running for his life.

It was a clear day, sharp and cold as a knife, but he couldn’t see a thing. The string that held the patch over his bad eye was slipping. The square of ancient leather slapped his face, disorienting him. He bounced off a drainpipe, did an ungainly whirl, kept running. Behind him, he heard the sound of a bell, coming after him, clanging furiously. Ahead was a gutter. He leaped into it and whistled over the frozen grime, sliding fast as anything. The gutter ended in a rusting grate. Pikey hurled himself over it, struck the cobbles running. His fingers went to the patch, trying desperately to tighten the string, but it wouldn’t stay, and he couldn’t stop. It was only about to get worse.

The cobble faery tripped him in Bluebottle Street.

There Pikey was, a knob of black bread clutched inside his jacket, pounding up a street that was as empty and icy as any in London. His pursuer was still two or three corners behind him. Pikey was sure he would get away. And then he felt the tremor in the ground beneath him, the rattle of the cobbles as a tiny faery raced through its secret tunnels. It popped up the stone just as Pikey’s foot was flying toward it.

Pikey let out a yelp and went careering into the wall of a house. His head knocked against stone. Pain shuddered through him, and he heard a wicked little voice sing, “Clumsy-patty, clumsy-patty, who’s a clumsy pitty-patty?”

Pikey spun, pushing himself away from the wall.

The faery was peeking out from under the lifted cobblestone, black-bead eyes glittering. It was a spryte, not three inches from head to toe. Bits of frosty branches grew behind its pointed ears and a dreadful grin was on its face, stretching halfway around. It was a very yellow grin, full of prickly little teeth.

“Shut up,” Pikey hissed. He ran at it, determined to smash it into a stringy mess. Too slow. The faery pulled down the cobble like a hat and was gone.

Pikey froze. He glanced back down the street, listening, making sure he still had some seconds to spare. Then he struck his boot heel against the ground three times, getting softer with each strike so that it would sound like he was walking away. The faery shot back up, still grinning. And Pikey leaped, straight onto the cobble. There was a squeak. The cobble smashed back into place. The faery’s hand twitched where it was pinched in.