Полная версия:

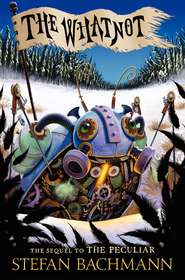

The Whatnot

To my family, who made me who I am

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

CHAPTER I: Snatchers

CHAPTER II: Hettie in the Land of Night

CHAPTER III: The Sylph’s Gift

CHAPTER IV: The Merry Company

CHAPTER V: Mr. Millipede and the Faery

CHAPTER VI: The Belusites

CHAPTER VII: The Birds

CHAPTER VIII: The Insurgent’s House

CHAPTER IX: The Pale Boy

CHAPTER X: The Hour of Melancholy

CHAPTER XI: The Scarborough Faery Prison

CHAPTER XII: The Masquerade

CHAPTER XIII: The Ghosts of Siltpool

CHAPTER XIV: The Fourth Face

CHAPTER XV: Tar Hill

CHAPTER XVI: A Shade of Envy

CHAPTER XVII: Puppets and Circus Masters

CHAPTER XVIII: The City of Black Laughter

CHAPTER XIX: Pikey in the Land of Night

CHAPTER XX: Lies

CHAPTER XXI: Truths

Epilogue

Have you read …?

Copyright

About the Publisher

Mr. Jelliby did not notice him either, not at first. He was busy being worried and a little bit irritated, leaning against the fireplace and watching the guests as they moved toward the dancing floor. The gentlemen were in full uniform, jangling with swords and medals of bravery, though most had not seen a day of battle. Red sashes slashed down their chests. The ladies smiled and whispered. Such bright birds, Mr. Jelliby thought. So happy. For tonight.

It was hot in the ballroom. The great windows were edged with ice, but inside it was a furnace. Candles were lit, the fire stoked, and the chandeliers burned so bright that the air around them rippled and the ceiling was heavy with smoke. Mr. Jelliby rubbed the hair above his ear, as if to scratch away the silver that was appearing there. He could smell the red currant tarts as they skimmed past. He could smell oil from the servants’ joints, and the damp wraps and overshoes lying in steaming heaps in the neighboring room. The orchestra was tuning up. Dear Ophelia was stooped over a sofa, trying to placate Lady Halifax, who seemed in constant peril of exploding. Mr. Jelliby felt he needed to sit down. He turned away from the mantel, looking for the most convenient escape. …

That was when he spotted the soldier.

Good heavens. Mr. Jelliby squinted. What were things coming to that you could get into a lord’s house dressed like that? The lad’s coat was filthy. The wool was sodden, the buttons dull, and the collar was black with who-knew-what. Had he been fresh off the battlefields it might have made some sense to Mr. Jelliby, but the Wyndhammer Ball was the going-off celebration. The war had not even started yet.

“Dashing good bash, this,” Lord Gristlewood said, sidling up to Mr. Jelliby and interrupting his thoughts. Mr. Jelliby jumped a little. Drat.

Lord Gristlewood was a droopy, fleshy man with pale, swollen hands that made Mr. Jelliby think of dead things soaking in jars of chemicals. Worse yet, Lord Gristlewood was the sort of man who thought everyone liked him even though no one actually did.

“Dashing good,” Mr. Jelliby said. He scanned the crowd, making a point to ignore the other man.

Lord Gristlewood did not take the hint. “Ah, would you look at them. … Brave lads, every one. The pride of England. Why, a thousand bellowing trolls could not frighten these men.”

Mr. Jelliby pressed his lips together.

“Well, don’t you think?” Lord Gristlewood asked.

“No, I don’t usually.” Mr. Jelliby spoke quietly, into his glass, hoping Lord Gristlewood wouldn’t hear.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Oh—That is—I certainly hope so!”

Lord Gristlewood smiled. “Of course you do! Cheer up, old chap. It’s a celebration, after all.”

“Indeed.” Mr. Jelliby set his glass down sharply on the mantel. “Well, old chap, if I’m to be honest with you, I see no reason to celebrate. We are entering into a civil war.”

Lord Gristlewood’s smile slipped a little bit.

Mr. Jelliby didn’t stop. “Tomorrow all you’ll hear is, ‘Hand in your wife’s jewels!’ and ‘Enlist your footman!’ and ‘All for the good of the empire!’ and other such bunk. And then the bodies will start coming back in sacks and wagons, and one will be your footman, and no one will be dancing then. It’s not a funny thing, fighting faeries.”

“Oh, but you are gloomful,” Lord Gristlewood said. “Come now. It’ll never go so far. The faeries are wild! They are leaderless and unorganized, and we shall settle them the way we settled the French. With our superior intellect. Let them come, I say. Let them strike us with all they’ve got. We won’t fall.” Lord Gristlewood gave an uneasy laugh and slid away, apparently deciding to grace a less depressing person with his presence.

Mr. Jelliby sighed. He picked up his glass again, turning it slowly. He took a sip. Over the glinting rim he saw the soldier, standing dark and solitary among the dancers.

Mr. Jelliby watched him a second. Then he smiled. Of course. The boy is shy! Why had he not thought of it before? No doubt the young soldier was frightened out of his wits and wondering how best to ask one of the ladies for a dance. Mr. Jelliby decided to go and rescue him. There was bound to be some equally unhappy nobleman’s daughter about, ideally lacking a sense of smell.

Mr. Jelliby pushed off into the crowd, setting course for the dancing floor at the center of the room. It was like navigating a sea of cotton candy, pressing between all those frocks. More and more couples were moving toward the dancing. In fact, the room seemed to be getting fuller by the second, not with people exactly, but with heat and laughter. Mr. Jelliby’s head began to buzz.

He had not gone ten steps when Lady Maribeth Skimpshaw—who moved within her very own atmosphere of rosy perfume—intercepted him, grabbing his arm and smiling. She had a very pink, gummy smile of the sort that comes with false teeth. Mr. Jelliby had heard she’d had her beginnings in London’s theater district, so doubtless all her real teeth had been traded for poppy potions and illegal faery droughts.

“Lord Jelliby! How perfectly delightful that I’ve found you. Your wife’s arm is going to fall off. She should stop fanning that odious Lady Halifax. The fool thinks someone’s stolen one of her gems, but she probably just forgot how many she put on this evening. No matter. I’ve kidnapped you and that’s what is important.” Her smile stretched. “Now. I know you are terribly busy managing your estates and counting your money and all that, but I absolutely must speak to you very urgently.”

“Oh dear, I hope not.”

“What?”

“I hope Ophelia’s arm doesn’t fall off. Shall I get you a tart?”

“No, Lord Jelliby, are you listening to me?” Her fingers tightened around his arm. “It’s about young Master Skimpshaw. I want to ask you a favor for him.”

Oh, drat again. People were always asking favors of Mr. Jelliby now that he was a lord. They asked for positions in government, or good words slipped to admirals, or whether he had any nonmechanical servants to spare. It drove him to distraction. Just because he had saved London from utter destruction and the Queen had given him a house and some stony fields in a distant corner of Lancashire did not mean he wanted to spend the rest of his life being charitable to aristocrats. Anyway, one would think they could handle their own problems.

“Terribly sorry, my lady, but you will have to find me later. Someone is in need of my assistance now, and”—Mr. Jelliby broke free of Maribeth Skimpshaw’s clutches—“and I really must be going.” He set off again toward the young soldier, trailing rose scent in ribbons behind him.

The orchestra was in full tilt now, sweeping everyone up in a glorious, whirling waltz. Mr. Jelliby could hardly see the soldier anymore. Only snatches of him, in between the spinning figures and bright gowns. His face was chalky. Drained, almost.

“Lord Jelliby? Oh, Arthur Jelliby!” someone called from across the room.

Mr. Jelliby walked faster.

And then, all at once, a rustle passed through the crowd, a disturbance, like the wind in the treetops before a storm. It started on the dancing floor and spread out until it had reached the farthest corners of the ballroom. The rustle swelled. Shouts, then a shriek, and then people were peeling away from Mr. Jelliby, backing up against the walls.

Mr. Jelliby stopped in his tracks.

The young soldier stood directly in front of him, not five paces away. He was alone, all alone on the polished floorboards. His hand was raised, stretched out in front of him. In it was clutched a bloody rag.

Mr. Jelliby let out a little cough.

The rag was blue, the color of England, the color of her army. Shreds of a red sash still clung to it. A spattered medal. The young soldier’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. He simply stared at the rag in his hand, a look of mild surprise on his white, white face.

The ballroom had gone deathly still. No one spoke. No one moved. The clockwork maids had all creaked to a halt. The old ladies were staring so hard their eyes seemed about to pop from their heads. Lady Halifax lay sprawled over a fainting couch, face red as an apple.

Mr. Jelliby’s first thought was, Good heavens, he’s killed someone, but he couldn’t see anyone hurt. No one seemed to be missing a piece of his uniform, nor were there any wounds visible among the swaths of lace and satin.

“Young man,” Mr. Jelliby started to say, unsteadily, taking a step toward the soldier. “Young man, what in—”

But he didn’t have time to say anything else, because suddenly the soldier began to change. As Mr. Jelliby watched, blood came up between the soldier’s teeth and gushed down his chin in a crimson sheet. Bright holes tore themselves through the fabric of his uniform. He spasmed, once, twice, as if being hit by some great, invisible force.

And then he began to fall, so slowly. Petals of black pulled away from his coat, his arms, and the side of his face as he descended through the air. There was a sound like distant guns. And before he struck the floor, he seemed to disintegrate, turn to ash and smoke and black powder.

Then he was gone, and the ladies were screaming.

Mr. Jelliby heard glass breaking. The lights were so hot now, so raging hot. He couldn’t smell the tarts anymore. Only the fear, thick as river mud in the rippling air.

It was a wonderful dream. He wasn’t in the bitter chill of his hole under the chemist’s shop anymore. The old wooden signboard with its painted hands and hawthorn leaves no longer creaked overhead, and the ice wasn’t crusting his face. In his sleep Pikey was warm, curled up by an iron stove, and the plums were drifting out of the dark, and he was eating a caramel apple that never seemed to get any smaller.

He always dreamed of caramel apples when he could help it. And iron stoves, too, in the winter. And plums and pies and loud, happy voices calling his name.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap. Far, far away on the other side of his eyelids, a figure entered the frozen alley.

Pikey bit down on his apple. He heard the footsteps, but he tried not to worry. Whoever it was would be gone soon. Folk were always stumbling into the chemist’s alley from Bell Lane, from the gutters and sluiceways and all the other fissures between the old houses of Spitalfields. None of them ever stayed for long.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.

Pikey squirmed inside his blankets. Go away, he thought. Don’t wake me up. But the footsteps kept coming, limping slowly across the cobbles.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.Pikey didn’t feel warm anymore. The plums still fell, but they stung now as they touched his skin, spitting, icy cold. He tried to take another bite of his apple. It turned to wind and cinders, and blew away.

Tap-tap. Tap-tap.

Snow was falling. Not plums. Snow. It gusted into his little hole, and suddenly Pikey’s nose was filled with the stench of old water and deep and mossy wells. A racket kicked up, old Rinshi straining against her chain, barking at something and then stopping, sharp-like. There was a grating, a scrape of metal.

Pikey saw the blood before he saw the figure, always the blood trickling toward him between the stones. Then the alley was filled with screams.

Pikey Thomas was running for his life.

It was a clear day, sharp and cold as a knife, but he couldn’t see a thing. The string that held the patch over his bad eye was slipping. The square of ancient leather slapped his face, disorienting him. He bounced off a drainpipe, did an ungainly whirl, kept running. Behind him, he heard the sound of a bell, coming after him, clanging furiously. Ahead was a gutter. He leaped into it and whistled over the frozen grime, sliding fast as anything. The gutter ended in a rusting grate. Pikey hurled himself over it, struck the cobbles running. His fingers went to the patch, trying desperately to tighten the string, but it wouldn’t stay, and he couldn’t stop. It was only about to get worse.

The cobble faery tripped him in Bluebottle Street.

There Pikey was, a knob of black bread clutched inside his jacket, pounding up a street that was as empty and icy as any in London. His pursuer was still two or three corners behind him. Pikey was sure he would get away. And then he felt the tremor in the ground beneath him, the rattle of the cobbles as a tiny faery raced through its secret tunnels. It popped up the stone just as Pikey’s foot was flying toward it.

Pikey let out a yelp and went careering into the wall of a house. His head knocked against stone. Pain shuddered through him, and he heard a wicked little voice sing, “Clumsy-patty, clumsy-patty, who’s a clumsy pitty-patty?”

Pikey spun, pushing himself away from the wall.

The faery was peeking out from under the lifted cobblestone, black-bead eyes glittering. It was a spryte, not three inches from head to toe. Bits of frosty branches grew behind its pointed ears and a dreadful grin was on its face, stretching halfway around. It was a very yellow grin, full of prickly little teeth.

“Shut up,” Pikey hissed. He ran at it, determined to smash it into a stringy mess. Too slow. The faery pulled down the cobble like a hat and was gone.

Pikey froze. He glanced back down the street, listening, making sure he still had some seconds to spare. Then he struck his boot heel against the ground three times, getting softer with each strike so that it would sound like he was walking away. The faery shot back up, still grinning. And Pikey leaped, straight onto the cobble. There was a squeak. The cobble smashed back into place. The faery’s hand twitched where it was pinched in.

“Serves you right, too,” Pikey said, but he had no time to enjoy his little victory. The bell was close now, echoing up between the buildings. An instant later, a huge officer in blue and crimson skidded into the street. A leadface.

“Thief!” the leadface shouted, his voice oddly flat and dull inside his iron half-helmet. “Thief!” But before he could see Pikey, Pikey was moving again, slipping under an archway and down a steep flight of steps, heart hammering.

The leadface charged up Bluebottle Street, flailing his bell. Pikey flattened himself against the gritty stone of the stairwell, just far enough down so that he could still see the street. He saw the black boots go by. He allowed himself a careful smile. The officer was running straight for the cobble faery. In five steps he would be flat on his face. Three. Two … And the officer kept right on running, hurtling toward the end of Bluebottle Street and the sooty flow of traffic on Aldersgate.

Oh. Pikey wiped his nose. Must have stomped that faery harder than I thought.

He leaned back against the slimy wall, waiting for the sound of the bell to become lost in the noise of the steam coaches and crowds. Then he strode up the steps and into the street, hands in his pockets, looking for all the world as if he had just gotten up and was off to sell matches or shine shoes or squawk the news at unsuspecting pedestrians.

Of course, he wasn’t. He had just snatched his supper and now he was going to find a quiet spot where he could eat it. Leadfaces were inconvenient; so were cobble sprytes, especially since they had supposedly been banned from the city months ago together with all the other faeries. But they were nothing Pikey Thomas couldn’t handle.

He picked his way back toward Spitalfields, careful to avoid the places where the leadfaces prowled and where the war agents sat at their painted recruiting booths. They were everywhere these days, and they went after most anyone they saw. “For Queen and Country!” they liked to bellow into their loudening horns. “For England, to eradicate the faery threat! Step right up, all men of hardy constitution!”

Pikey didn’t know if he had a hardy constitution, but he knew he couldn’t go to war. A year ago he would have. He was only twelve, but he would have signed up in an instant. The army had bread. It had thick coats and colorful banners and great bashing songs that made your feet want to march even if they didn’t know where they were going. And you got a musket, too, for shooting faeries, which sounded good to Pikey. But that was before. Before the snowy night in the chemist’s alley, and the blood between the cobbles, and the feet limping closer, straight toward him no matter how far he pressed himself into the dark. Before everything changed and he didn’t know what he was anymore.

From an alley, Pikey watched as a group of boys not fourteen hunched over a war agent’s table and signed their Xs on squares of brown card paper. When they had finished, the leadface handed them each a coat and a pair of huge scuffed boots. Then the boys were loaded into a wagon and it creaked away.

The leadface at the booth began scanning the passersby again, eyes invisible behind the dark holes of his helmet. Pikey hurried on. Those boys would be fighting soon, somewhere in the North. Fighting forests and rivers and whispery magic nonsense. He wondered if their boots would come back to London afterward, when they were gone, and be given to other boys.

He went up street after street, ducking into alleys when he heard the leadfaces’ shouts, hurrying beneath the drooping, blackened houses. They had been the mansions of the faery silk weavers once. Now they were the houses of pickpockets and bloodletters and the poorest of the poor. Sometimes a woman leaning out of a window, or another boy in the street, would spot Pikey and shout, “Oy, pikey!” in a not-very-nice voice. Pikey always hurried faster then.

Pikey wasn’t his real name. Or Thomas, either, for that matter. “Pikeys” were what folks called foreigners, and because Pikey had a face as brown as an old penny (whether from dirt or because he actually was a foreigner not even he knew), the name had stuck. As for Thomas, it was the name on the box he had come in, twelve years ago on a doorstep in Putney: Thomas Ltd. Crackers and Biscuits. Premium quality.

People had thought that funny once, coming from a cracker box. Pikey didn’t think it was funny at all.

In the pigeon-choked space in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral, a gang of boys accosted him.

“Give you a ha’penny if you show us your socket,” the oldest and tallest one snarled. He wore a blue coat with brass buttons, much too big for him, and a pair of boots with popped toes. He looked like the leader.

The other boys crowded around, prodding Pikey, dirty faces pressing in. “Yeh, show us your socket! What happened, eh? Did you see something you weren’t supposed to? Did Jenny Greenteeth pluck it out and string it up for a necklace?”

If Pikey’d had a socket he would have taken the boys’ offer in an instant. A ha’penny could buy him a proper meal, let him sit in the warmth and stink of an inn and eat potatoes and gravy and gray boiled mutton until he burst. But he didn’t have a socket, and the boys wouldn’t like what they saw.

“Shove off. Leave me alone.”

“Aw, come on, piker. Just a peek? Whada you say, fellas, you think we can see his brains through it? What say I pull off the patch and we get a look-see at his brains, all yellow and squishy inside.”

The boys murmured their assent, some more readily than others. The gang leader stepped forward, reaching for Pikey’s patch. Pikey braced himself for a fight.

“I said, shove off!” His voice went hard like a proper street rat’s, but he was too short to make it count. The boy in the brass-button coat kept coming.

Pikey ducked away, ready to run, but two of the boys grabbed his arms and pinned them behind his back.

“You stay where you’re put at,” one of them whispered, close next to his ear.

“Help!” Pikey croaked. There were people everywhere. Someone would hear him. Or see. The spot in front of St. Paul’s was one of the busiest in London, even in winter, even with the sky going black overhead. Costermongers shouted from their pushcarts, offering lettuces and cabbages and suspicious-looking roots. Peddlers haggled, servants bought. A red-and-gold striped cider booth stood not ten paces away, with a whole line of people waiting in front of it. They couldn’t all be deaf.

“Help, thief!” he cried.

No one even glanced at him.

“Stop cryin’ like a little pansy. We only want a quick look. Shut up, I say. Shut up, or you’ll get us all in trouble.” The leader planted a heavy fist in Pikey’s stomach, and his next shout came out in a puff of white breath.

He hung for a second, gasping, his arms still clamped behind him. He felt the leader’s fingers undoing the string of the eye patch, pulling it off.

“We only want a quick look—”

Pikey shut his eyes hard and threw himself back with all his strength. His head thudded against the head of the boy behind him and they both went down, rolling over the cobbles. Pikey landed on the other boy’s stomach with a satisfying squelch and sprang back up, one hand covering the place where the patch had been, the other swinging wildly.