Полная версия:

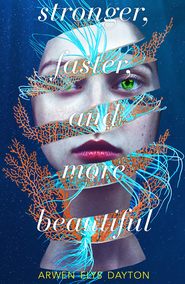

Stronger, Faster, and More Beautiful

“Here I am,” I say.

The hospital room is empty except for me, so I can get away with talking to myself without drawing frowns from the nurses. I lay a hand across the mess of staples down my breastbone. “And here you are,” I tell Julia. “Keeping me alive.”

She doesn’t answer. It’s rainy today, and the only response I get is the patter of raindrops on the hospital window. Even if you’re one of those people who love the rain, I think you’ll agree that the things it says are, at best, extremely boring. At worst, they’re only raindrops, which are no substitute for your dead twin sister.

“Dead,” I say, trying out the word that I haven’t let myself think. I’ve shied away from it since the operations. Now that I’ve said it aloud, though, I have to ask her what I’ve been afraid to ask.

“Julia, were you dead when they took out your heart? Or did I steal it from you while you were still alive?”

She doesn’t answer. Of course, she doesn’t need to. Everyone—the doctor, my parents, the nurses—danced around this question. But I always knew the truth.

I am growing again.

It’s been twelve days since the last surgery and there’s enough oxygen in my blood, and my digestive system actually gets nutrition out of the food I eat, and and and and, you know, all the things the doctor optimistically suggested would happen, are happening. I’ve grown an eighth of an inch and gained three pounds. That eighth of an inch, by the way, makes me as tall as Julia was, though I’ll keep growing, they assure me. I might even get as tall as my father.

“Fortune has been smiling on us all this time, Evan,” my father is saying. Did I mention he was in here with me? He is. He’s helping me get into my clothes. I’m strong enough to dress myself, but I’m letting him feel useful.

My mother’s here too, though she’s outside the room, to give me privacy while I get dressed, and probably also because she feels guilty about letting Reverend Tadd crap all over the last few minutes I had with my sister.

They’re releasing me from the hospital today. Over the past several years, Julia and I have spent a combined total of over five hundred days here. During those five hundred days, I’ve imagined this final day many times. In my favorite version, we walk out the front doors, and shortly afterward, the hospital is leveled by an earthquake, and then ripped apart by a tornado, and then set on fire by roving bands of zombies. After that, if “fortune keeps smiling on us,” packs of wild dogs will urinate all over the rubble as a warning never to rebuild.

“It’s nice to see you smiling, Evan,” my dad says, when my head emerges from the sweater he’s pulling into place over my Frankenstein torso.

I decide to let him in on the daydream. “I was thinking that after we walk out of the hospital’s front doors—”

“You know we’re going to wheel you out in a wheelchair, right? No walking just yet. But soon!” he tells me cheerfully.

“Oh, right,” I say. He is so literal.

Every doctor and nurse on this floor is lining the hallway as I’m wheeled toward the elevator by my parents. Even some of the more mobile patients are standing in their doorways to watch us, the medical pioneers. My father waves and smiles at all of them. My mother is soundlessly mouthing thank you, as though she were always one hundred percent behind this whole cannibalize-your-sister’s-organs scenario.

I’m dying to hear what Julia would say about this sad parade to the elevator. Would she tell me to feign a stroke? Or clutch my heart?

“That’s right, smile,” my father says quietly. “Let them see how grateful you are.”

Am I grateful? I haven’t heard her voice for two weeks.

In the main lobby, and the world outside is visible through the huge glass doors. My mother’s gone off to pull the car around, and when we see her driving into the pickup area, my dad says, “Here we go,” and pushes me out through the doors.

“Oh!” I cry out, because the strangest thing happens the moment I cross the threshold: the super-heart stops. There’s a heartbeat, and then there is nothing, stretching out from one instant to the next and the next and the next. I cannot breathe, I cannot move. My super-heart has walked off the job without giving notice.

My father’s smile falters, and then, in a panic, he shakes me. “Evan? Evan! Is it your heart?”

There’s a thunk! in my chest as the heart starts up again. Then, thump-thump, thump-thump, it’s going—as if nothing at all went wrong. If anything, I feel a new surge of vitality.

“Evan?” he says again, frantically.

I wave him away. “My heart … is fine,” I tell him.

“Are you sure?” He looks back through the doors, ready to flag someone down.

I nod, give him an emphatic thumbs-up. My mother has pulled the car up right in front of us, so I push myself to my feet, and before he can even catch up to me, I’ve opened the back door of the minivan and climbed inside. In moments, we’re all in the car and my mother is driving away.

I watch the hospital growing smaller as we get to the end of the street. When at last I can see only a sliver of the hospital’s upper floor above neighboring buildings and it’s about to disappear from sight entirely, I think, Cue the earthquake!

Julia should laugh at that, but she doesn’t. I’m sitting in the back of the minivan alone, looking past my parents at the road ahead. Traffic and life are out there, ready to take me in.

It’s not until we are stopped at a long traffic light that I hear it. Very quietly, a voice asks, Do you want to kill all the other patients? The voice sounds not so much upset as curious, and it’s as soft as the murmur of an insect or a mouse.

I’m so startled, so unsure of what I’ve heard, that I can only bring myself to whisper an answer. “I don’t mind if they’re all evacuated first,” I breathe. “But the building has to go.”

There’s silence in response and I sit there, holding my breath. I’ve imagined the voice; it’s nothing but my hopeful ears playing tricks on me. The quiet stretches on as we travel through the city. My ears strain for anything besides the noise of the traffic, and they are disappointed.

But when we’ve gone a very long way and the hospital is nothing more than an anonymous mass far behind us, I hear this:

I agree. The hospital building has to go. The voice is growing as it speaks. It’s not a mouse’s voice anymore, it’s a kitten’s. So …, it says, growing into a child’s voice, what were the results of the operation?

“Just the usual,” I whisper, for fear of scaring her away. “You know, new heart, liver, pancreas, blah, blah, blah.”

No new brain? she asks. Her voice has become her real voice.

I shake my head.

So they screwed up the one thing you actually needed?

I nod. And smile.

Did you hear about that kid who was taken into the operating room, but then he had a change of heart?

“He didn’t know if he was going to liver die,” I whisper.

Aorta laugh at that.

“Like me—I’m in stitches.”

I don’t mean to cry, but tears spring to my eyes and a bunch of them are pushed out by a sudden burst of laughter that is incredibly painful to all of my recently sutured parts, which doesn’t make it any less magical.

“You were so quiet,” I whisper.

That was on account of being dead, she tells me. By the way, I heard you call it “your heart.” That was a little cold.

“I didn’t mean it,” I say, squirting out another set of unstoppable tears. “I meant our heart.”

I’ve said this last part loudly, and my father and mother both turn back to look at me.

“Our heart!” I say again to her.

“That’s right, Evan. Our heart,” my father says.

Is he serious? Julia asks. Are they going to take credit for everything forever?

“Probably,” I answer.

Julia sighs. Eventually she says, I guess it doesn’t matter what they think. What do we care?

There.

She has said it: we.

And I am happy.

I invite you to look beyond the current capabilities of tissue and bone repair. Those will soon become unremarkable. In a very short time, we will be able to create novel structural elements, forms that don’t naturally occur in the human body—forms that we haven’t yet imagined. I find myself a pioneer, daunted by the infinite size of the frontier.

—Dr. Emily Brownstone-Naik, at the British Medical Association symposium on genetic engineering, London, 2029

A few more years from now …

1. GO GET ’EM TIGER

How can I tell you what happened in the right way? If I explain it wrong, you’ll probably hate me. But if I can tell it right, maybe you’ll understand.

I knew he saw me inside Go Get ’Em Tiger, which serves coffee so good I actually tingle all along the border of … parts of me. I knew Gabriel saw me inside, even though his eyes slid past me, as though he were just looking, just browsing, just checking out the bags of coffee beans and logo mugs for sale on the shelves along the walls and not seeing Milla sitting right there, staring at him over the top of my newspaper. Before you ask, I’ll answer: Yes. I’m a sixteen-year-old girl who gets the newspaper, by special order, delivered twice a week, because I do the crossword puzzle, because it focuses me, and when I focus, I relax, and when I relax … well, things work right—like my lymph system and most of my hormones. The doctors all agreed that I needed to find calming techniques,and this is one. Plus, holding a newspaper is deliciously retro; it makes me feel like a girl from the year 2015, to whom nothing catastrophic has ever happened.

But back to Gabriel. He ignored me. It was so crowded, he had plausible deniability, and I had … I had the echoes of thirty people laughing at me the week before as I shoved my lunch into the trash can and ran out of the school courtyard. Not crying. If I could have cried, that would have been awesome.

But why had the laughing bothered me so much? There was a story in the newspaper I was holding about a teenager beaten into unconsciousness in the stands of his high school football stadium in Ohio. He’d had one of those partial spinal replacements where he could walk, but not a hundred percent properly. His assailants had been watching his gait when he got to his seat. They’d waited out the whole game, and then they’d attacked him at the end and spray-painted the word WRONG across his chest. They were drunk teenagers, but still, it was an example of the way some people were offended by anyone who’d been severely damaged and then put back together. “Fanatics Behaving Badly” was practically a regular newspaper column. In my case, you couldn’t tell what had happened to me. I walked normally, I spoke normally. You wouldn’t know, unless somebody told you. And I’d only had to put up with laughter.

Gabriel left Go Get ’Em Tiger and I watched through the window as he stood on the sidewalk outside, rooting around in the brown paper pastry bag he’d gotten with his cappuccino. He’s kind of tall, and I could keep an eye on him easily among the crowds of passersby. He had those headphones that hide behind your ear, and he idly tapped his right ear to turn them on—just a guy eating a scone and listening to music.

He didn’t spare a glance back to see if I was watching him. And he also wasn’t trying to get away quickly. Maybe he hadn’t seen me after all. But that was worse in a way, wasn’t it? That would make me just wallpaper or something, not even enough of a presence to ignore. Anger made my heart beat faster. It was necessary to go after him.

Gabriel took another bite of scone and I drained my mug, already feeling the tingle of the caffeine along the meshline and furious that he’d ruined my coffee time by being there. (Okay, I’ve said it. Meshline. There’s a meshline zigzagging through my body. It’s why I’m here now instead of in a grave or cremated or whatever. Fair warning, zealots: you can turn away right now if my existence offends you.)

When I was out on the sidewalk, I caught sight of him at the crosswalk. Well … no. I want to be honest. The truth is that I searched the crowds wildly until I spotted him again, and then I fought my way over.

What was I thinking at that moment? I’ve asked myself this question a hundred times. And the answer is this: I wanted to radiate my fury, my humiliation, at him. That’s all. I’m pretty sure that was all I wanted.

The light there takes forever, and a bunch of people were waiting at the crosswalk. Next to me was a girl with a subdermal bracelet implant, and for a moment I was distracted by the patterns it was projecting up through her skin. Flickering lights danced around her wrist, looking too cheerful with her heavy black makeup and the safety pins through her eyebrows. She obviously didn’t mind tinkering with herself, and no one nearby seemed to mind either. But some of them probably did.

It was hard to breathe. I wanted to cry.

The sound of Gabriel slurping his coffee brought me back. He was right at the curb and I was directly behind him. He turned his head, so I could see his face in profile. It was so odd. He was still really good looking, all blond, with dark brown eyes and thick lashes and that square jaw. But his looks had morphed into something I associated with pain, and staring at him wasn’t the same as it had been a week ago.

I thought, Can’t he feel me standing here boring holes into his back with my eyes?

Obviously he couldn’t.

The traffic from the north was coming at us—four lanes at full speed, half of the vehicles without drivers, including a huge, automated City of LA bus that filled up an entire lane. The noise of the cars was punctuated by the constant whine of the air-drones that fly north and south above La Brea Avenue all day, along the route to the airport. I could have whispered Gabriel’s name and he wouldn’t have heard me. I didn’t, though. I gave him no warning, other than my silent, hostile presence.

I stepped forward so I was right behind him, reached out my hands …

Shit. You’re going to hate me.

I have to start earlier.

2. CHURCH BELL

I go to an Episcopal school that only has about three hundred students. Everyone knows everyone, even if everyone isn’t friends with everyone, if that makes sense. I’m pretty smart, maybe a little bit nerdy, but honestly, a lot of kids at my school are smart and a little nerdy. I’m reasonably good looking, but again, there are plenty of good-looking girls at St. Anne’s. So I’m average, socially, economically, academically. Is this even relevant to my story? I don’t know. It’s possible I’m stalling.

So.

A week earlier, a week before what happened outside Go Get ’Em Tiger, my mom dropped me off at school. I’d been leaning against the passenger door, using the minimum possible number of words to respond to her attempts at good-morning-sweetheart-how-are-things conversation. Then, just as we arrived, she asked the question she’d probably been working up the courage to ask all along: “How was your date last night?”

My reaction surprised even me. My dark mood snapped into something worse, something that could not be contained in sullen silence. Without any warning, I yelled, “Can’t you let me live my own life for one second, Mom, for chrissakes? I’m not five! Can’t I keep a secret if I want?”

I slammed the door behind me, leaving her sitting behind the wheel, shocked but resigned. (“Just let her be angry,” my father was always saying.) I stomped off into the main building, knowing that fury directed at my mother was ridiculous and unfair. And seriously, how would her asking me about my date imply that I was five years old? There was no logic. Also this: I hadn’t meant to yell, I honestly hadn’t, but it’s weird what I can and can’t regulate. Sometimes the volume of my voice is in the “can’t” category.

People at school were looking at me, but, you know, obviously, I thought, because I’d just slammed the car door like a five-year-old. It wasn’t until my friend Lilly caught my arm, pulled me into that weird little alcove by the trophy case, and whispered, “Did you really, Milla? You hardly even know him,” that I realized I had no secret to keep. Everyone already knew.

I walked to class feeling like an accident victim staring back at the rubberneckers who’d slowed down to watch me bleeding all over the roadside. That last part had literally happened to me, though when it did, I wasn’t awake to watch. I don’t even think I was alive.

I digress.

Kevin Lopez smirked as he leaned against the wall. Next to him, Kahil Neelam was making a weird hand gesture at me—he was using one hand to snap at the pointer finger of his other hand, like a fish biting a stick.

I was pushing through my homeroom door when I saw Matthew Nowiki—Matthew, who had been my friend since middle school—doing the robot and snickering as his gaze swept over me. He disappeared into his own homeroom, but not before snapping his fingers, pointing, and bestowing upon me a dramatic wink.

I had taken a seat at my desk when I realized what Kahil’s hand gesture had meant. The pointer finger had been a penis, and the other hand grabbing it was supposed to be a robot vagina crushing it, over and over.

Humiliation spread between my organs like sticky black tar. Heat bloomed across my face, informing me that I was turning red. The thing is that I don’t really blush anymore, because blushing, in my current configuration, is almost impossible. That it was happening now meant so much adrenaline was flooding into my blood, it was literally bypassing the entire meshline to set my face aflame. I was blushing and sweating, which attracted everyone’s attention.

Just kidding. They were already looking at me anyway.

“I don’t even see where …” I heard behind me in a loud whisper.

“How did he even …,” someone else asked.

“He has no fear, obviously,” a third person said, in a whisper so loud people on the other side of the city probably heard it.

This would have been an excellent time to cry. But I haven’t managed to do that in a year. Instead, I sat through my morning classes as the humiliation slowly hardened into something else.

At lunch, I went up to Gabriel in the courtyard where we all ate and I threw my soup in his face. It felt wonderful, it felt like vindication, even though the soup was lukewarm clam chowder and didn’t make much of an impact. Still, every person in the courtyard was watching me as I screamed, “How could you be such an enormous dick?”

Looking back, I realize this wasn’t the worst insult I could have chosen. I’m not sure anyone noticed my phrasing, though, because the words had come out so unbelievably loud that I thought the church bell on top of the chapel had somehow rung at the exact moment I opened my mouth.

It wasn’t the church bell. It was my voice. Gabriel stared at me, spellbound.

Jesus H. Christ, this is still making it look as though I came after Gabriel like the unhinged robot girl people were whispering that I was. Correction: no one was actually whispering. At that moment, Kahil Neelam, a few yards away from Gabriel in the courtyard, was yelling, “Does not compute! Does not compute!” again and again and miming smoke coming out of his ears. He was pretending to be me. Get it?

I’m sorry for using Jesus’s name to swear. I’m trying to be better about that. I’m pretty sure Jesus would be solidly on my side, so I don’t want to piss him off too.

Shit.

I have to explain the night itself.

The drive-in movie and the making out.

I’m blushing even to think about it. (I’m not, though. There’s a sensation in my cheeks, but no redness—I checked in the bathroom mirror. Sometimes things work and sometimes they don’t. I’m glitchy.)

Anyway.

3. CAST OF THOUSANDS

It was the night before that day in school. We were at Cast of Thousands, the drive-in movie theater in Sherman Oaks with the huge screen that doubles onto your own car’s windshield. You look through the movie image on the windshield to the much larger screen in the distance and somehow your eyes combine both into the most oh-my-God-that’s-incredible 3D image. The sound was piped directly into the car’s stereo system, so it was like our own private movie, and I was in Gabriel Phillips’s car.

I haven’t explained my history with Gabriel because there was no history, except for a long trail of lustful thoughts that were, as far as I knew, all on my side. Still, I should fill you in. He came to our school when he was fourteen. He was kind of gangly and his voice was still kind of high, but the blond hair and dark eyes really got to me. I became weirdly focused on his hands too, which were too big for the rest of him, the hands of a man, I thought, and right away I wanted them to touch me. It was the first time I had ever lain in bed and imagined a specific boy doing specific things to me. Jonas and I had been boyfriend and girlfriend before he moved away (before I’d even met Gabriel) and we’d actually done specific things, but I’d never fantasized about Jonas. I’d never had to; he was always with me. The at-a-distance crush on Gabriel was something new.

Other girls liked Gabriel too, in a more general way—he was good-looking and he went to our school, so, yeah, he was naturally on the list of Guys to Like. It wasn’t until he was fifteen and had shoulders and biceps and a deep voice, though,that other girls really started to pay attention. They liked him when he was an obvious choice. I’d liked him so much longer. He flirted with girls at school, but the rumor was that he had “other girlfriends” outside our little St. Anne’s group.

I thought about him for a year, and then in the hospital, when the lights were off for the night and I was alone with the sounds of machines that were keeping me alive, while the meshline and its various internal components were being created, I thought about him some more. That fantasy Gabriel diverged more and more from the one I had vaguely known at school, until, when I finally returned to St. Anne’s, it took me a moment to recognize him. But only a moment. Then the real-world crush was back, as strong as ever.

So here we were, in his car together, the first time I’d even been alone with him. We were in the front seats, with a cardboard tray of tacos between us, and I’m not going to lie to you, the conversation was awkward. In my imagination, conversation hadn’t been necessary, if you know what I mean. Fantasy Gabriel had done whatever I wanted. But here we were, stuck with words.

“Is the volume okay?” he asked, fiddling with the knob unnecessarily. It felt like our taco tray was the Pacific Ocean and he was all the way on the other side of it, by Japan, maybe.

“It’s fine,” I answered.

“Seems like we never really talked before this year. Why is that?” he asked. Before I could answer, he added, “When you came back to school, I realized that—that I wanted to get to know you.”

“Yeah, me too,” I said, trying not to stare at his sexy hands. “We’ve been at the same school for almost three years. Why don’t we know each other better?”