Полная версия

Полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

In the course of these operations, and in support of them, the British Navy had created a post at Tangier Island, ten miles across the bay, opposite the mouth of the Potomac.363 Here they threw up fortifications, and established an advanced rendezvous. Between the island and the eastern shore, Tangier Sound gave sheltered anchorage. The position was in every way convenient, and strategically central. Being the junction of the water routes to Baltimore and Washington, it threatened both; while the narrowness of the Chesapeake at this point constituted the force there assembled an inner blockading line, well situated to move rapidly at short notice in any direction, up or down, to one side or the other. At such short distance from the Patuxent, Barney's movements were of course well under observation, as he at once experienced. On June 1, he left the river, apparently with a view to reaching the Potomac. Two schooners becalmed were then visible, and pursuit was made with the oars; but soon a large ship was seen under sail, despatching a number of barges to their assistance. A breeze springing up from southwest put the ship to windward, between the Potomac and the flotilla, which was obliged to return to the Patuxent, closely followed by the enemy. Some distant shots were exchanged, but Barney escaped, and for the time was suffered to remain undisturbed three miles from the bay; a 74-gun ship lying at the river's mouth, with barges plying continually about her. The departure of the British schooners, however, was construed to indicate a return with re-enforcements for an attack; an anticipation not disappointed. Two more vessels soon joined the seventy-four; one of them a brig. On their appearance Barney shifted his berth two miles further up, abreast St. Leonard's Creek. At daylight of June 9, one of the ships, the brig, two schooners, and fifteen rowing barges, were seen coming up with a fair wind. The flotilla then retreated two miles up the creek, formed there across it in line abreast, and awaited attack. The enemy's vessels could not follow; but their boats did, and a skirmish ensued which ended in the British retiring. Later in the day the attempt was renewed with no better success; and Barney claimed that, having followed the boats in their retreat, he had seriously disabled one of the large schooners anchored off the mouth of the creek to support the movement.

There is no doubt that the American gunboats were manfully and skilfully handled, and that the crews in this and subsequent encounters gained confidence and skill, the evidences of which were shown afterwards at Bladensburg, remaining the only alleviating remembrance from that day of disgrace. From Barney would be expected no less than the most that man can do, or example effect; but his pursuit was stopped by the ship and the brig, which stayed within the Patuxent. The flotilla continued inside the creek, two frigates lying off its mouth, until June 26, when an attack by the boats, in concert with a body of militia,—infantry and light artillery,—decided the enemy to move down the Patuxent. Barney took advantage of this to leave the creek and go up the river. We are informed by a journal of the day that the Government was by these affairs well satisfied with the ability of the flotilla to restrain the operations of the enemy within the waters of the Chesapeake, and had determined on a considerable increase to it. Nothing seems improbable of that Government; but, if this be true, it must have been easily satisfied. Barney had secured a longer line of retreat, up the river; but the situation was not materially changed. In either case, creek or river, there was but one way out, and that was closed. He could only abide the time when the enemy should see fit to come against him by land and by water, which would seal his fate.364

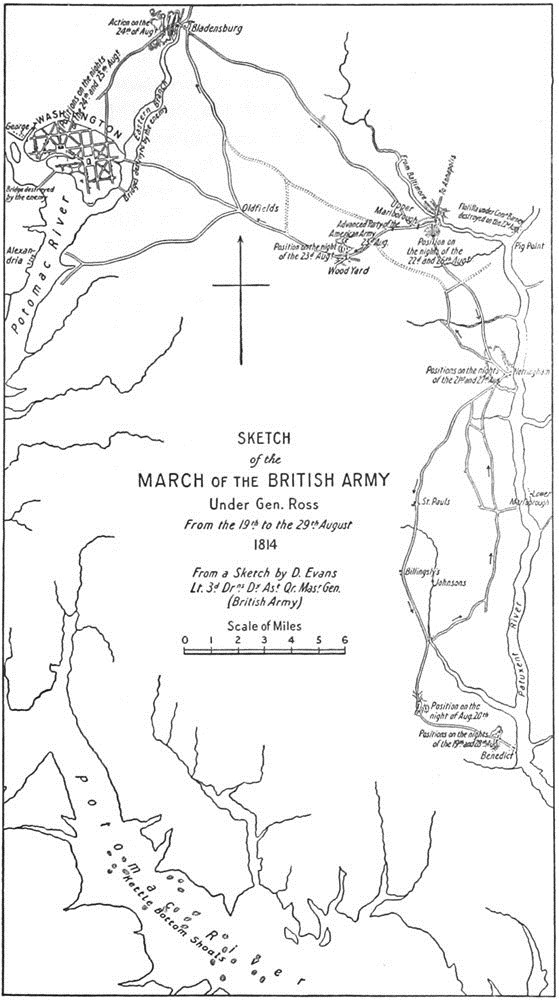

On June 2 there had sailed from Bordeaux for America a detachment from Wellington's army, twenty-five hundred strong, under Major-General Ross. It reached Bermuda July 25, and there was re-enforced by another battalion, increasing its strength to thirty-four hundred. On August 3 it left Bermuda, accompanied by several ships of war, and on the 15th passed in by the capes of the Chesapeake. Admiral Cochrane had preceded it by a few days, and was already lying there with his own ship and the division under Rear-Admiral Cockburn, who hitherto had been in immediate charge of operations in the bay. There were now assembled over twenty vessels of war, four of them of the line, with a large train of transports and store-ships. A battalion of seven hundred marines were next detailed for duty with the troops, the landing force being thus raised to over four thousand. The rendezvous at Tangier Island gave the Americans no certain clue to the ultimate object, for the reason already cited; and Cochrane designedly contributed to their distraction, by sending one squadron of frigates up the Potomac, and another up the Chesapeake above Baltimore.365 On August 18 the main body of the expedition moved abreast the mouth of the Patuxent, and at noon of that day entered the river with a fair wind.

The purposes at this moment of the commanders of the army and navy, acting jointly, are succinctly stated by Cochrane in his report to the Admiralty: "Information from Rear-Admiral Cockburn that Commodore Barney, with the Potomac flotilla, had taken shelter at the head of the Patuxent, afforded a pretext for ascending that river to attack him near its source, above Pig Point, while the ultimate destination of the combined force was Washington, should it be found that the attempt might be made with any prospect of success."366 August 19, the troops were landed at Benedict, twenty-five miles from the mouth of the river, and the following day began their upward march, flanked by a naval division of light vessels; the immediate objective being Barney's flotilla.

For the defence of the capital of the United States, throughout the region by which it might be approached, the Government had selected Brigadier-General Winder; the same who the year before had been captured at Stoney Creek, on the Niagara frontier, in Vincent's bold night attack. He was appointed July 2 to the command of a new military district, the tenth, which comprised "the state of Maryland, the District of Columbia, and that part of Virginia lying between the Potomac and the Rappahannock;"367 in brief, Washington and Baltimore, with the ways converging upon them from the sea. This was just seven weeks before the enemy landed in the Patuxent; time enough, with reasonable antecedent preparation, or trained troops, to concert adequate resistance, as was shown by the British subsequent failure before Baltimore.

The conditions with which Winder had to contend are best stated in the terms of the Court of Inquiry368 called to investigate his conduct, at the head of which sat General Winfield Scott. After fixing the date of his appointment, and ascertaining that he at once took every means in his power to put his district in a proper state of defence, the court found that on August 24, the day of the battle of Bladensburg, he "was enabled by great and unremitting exertions to bring into the field about five or six thousand men, all of whom except four hundred were militia; that he could not collect more than half his men until a day or two previously to the engagement, and six or seven hundred of them did not arrive until fifteen minutes before its commencement; … that the officers commanding the troops were generally unknown to him, and but a very small number of them had enjoyed the benefit of military instruction or experience." So far from attributing censure, the Court found that, "taking into consideration the complicated difficulties and embarrassments under which he labored, he is entitled to no little commendation, notwithstanding the result; before the action he exhibited industry, zeal, and talent, and during its continuance a coolness, a promptitude, and a personal valor, highly honorable to himself."

The finding of a court composed of competent experts, convened shortly after the events, must be received with respect. It is clear, however, that they here do not specify the particular professional merits of Winder's conduct of operations, but only the general hopelessness of success, owing to the antecedent conditions, not of his making, under which he was called to act, and which he strenuously exerted himself to meet. The blame for a mishap evidently and easily preventible still remains, and, though of course not expressed by the Court, is necessarily thrown back upon the Administration, and upon the party represented by it, which had held power for over twelve years past. A hostile corps of less than five thousand men had penetrated to the capital, through a well populated country, which was, to quote the Secretary of War, "covered with wood, and offering at every step strong positions for defence;"369 but there were neither defences nor defenders.

The sequence of events which terminated in this humiliating manner is instructive. The Cabinet, which on June 7 had planned offensive operations in Canada, met on July 1 in another frame of mind, alarmed by the news from Europe, to plan for the defence of Washington and Baltimore. It will be remembered that it was now two years since war had been declared. In counting the force on which reliance might be placed for meeting a possible enemy, the Secretary of War thought he could assemble one thousand regulars, independent of artillerists in the forts.[2] The Secretary of the Navy could furnish one hundred and twenty marines, and the crews of Barney's flotilla, estimated at five hundred.[2] For the rest, dependence must be upon militia, a call for which was issued to the number of ninety-three thousand, five hundred.370 Of these, fifteen thousand were assigned to Winder, as follows: From Virginia, two thousand; from Maryland, six thousand; from Pennsylvania, five thousand; from the District of Columbia, two thousand.371 So ineffective were the administrative measures for bringing out this paper force of citizen soldiery, the efficiency of which the leaders of the party in power had been accustomed to vaunt, that Winder, after falling back from point to point before the enemy's advance, because only so might time be gained to get together the lagging contingents, could muster in the open ground at Bladensburg, five miles from the capital, where at last he made his stand, only the paltry five or six thousand stated by the court. On the morning of the battle the Secretary of War rode out to the field, with his colleagues in the Administration, and in reply to a question from the President said he had no suggestions to offer; "as it was between regulars and militia, the latter would be beaten."372 The phrase was Winder's absolution; pronounced for the future, as for the past. The responsibility for there being no regulars did not rest with him, nor yet with the Secretary, but with the men who for a dozen years had sapped the military preparation of the nation.

Under the relative conditions of the opposing forces which have been stated, the progress of events was rapid. Probably few now realize that only a little over four days elapsed from the landing of the British to the burning of the Capitol. Their army advanced along the west bank of the Patuxent to Upper Marlborough, forty miles from the river's mouth. To this place, which was reached August 22, Ross continued in direct touch with the navy; and here at Pig Point, nearly abreast on the river, the American flotilla was cornered at last. Seeing the inevitable event, and to preserve his small but invaluable force of men, Barney had abandoned the boats on the 21st, leaving with each a half-dozen of her crew to destroy her at the last moment. This was done when the British next day approached; one only escaping the flames.

The city of Washington, now the goal of the enemy's effort, lies on the Potomac, between it and a tributary called the Eastern Branch. Upon the east bank of the latter, five or six miles from the junction of the two streams, is the village of Bladensburg. From Upper Marlborough, where the British had arrived, two roads led to Washington. One of these, the left going from Marlborough, crossed the Eastern Branch near its mouth; the other, less direct, passed through Bladensburg. Winder expected the British to advance by the former; and upon it Barney with the four hundred seamen remaining to him joined the army, at a place called Oldfields, seven miles from the capital. This route was militarily the more important, because from it branches were thrown off to the Potomac, up which the frigate squadron under Captain Gordon was proceeding, and had already passed the Kettle-bottoms, the most difficult bit of navigation in its path. The side roads would enable the invaders to reach and co-operate with this naval division; unless indeed Winder could make head against them. This he was not able to do; but he remained almost to the last moment in perplexing uncertainty whether they would strike for the capital, or for its principal defence on the Potomac, Fort Washington, ten miles lower down.373

SKETCH of the MARCH OF THE BRITISH ARMY Under Gen. Ross From the 19th. to the 29th. August 1814

For the obvious reasons named, because the doubts of their opponent facilitated their own movements by harassing his mind, as well as for the strategic advantage of a central line permitting movement in two directions at choice, the British advanced, as anticipated, by the left-hand road, and at nightfall of August 23 were encamped about three miles from the Americans. Here Winder covered a junction; for at Oldfields the road by which the British were advancing forked. One division led to Washington direct, crossing the Eastern Branch of the Potomac where it is broadest and deepest, near its mouth; the other passed it at Bladensburg. Winder feared to await the enemy, because of the disorder to which his inexperienced troops would be exposed by a night attack, causing possibly the loss of his artillery; the one arm in which he felt himself superior. He retired therefore during the night by the direct road, burning its bridge. This left open the way to Bladensburg, which the British next day followed, arriving at the village towards noon of the 24th. Contrary to Winder's instruction, the officer stationed there had withdrawn his troops across the stream, abandoning the place, and forming his line on the crest of some hills on the west bank. The impression which this position made upon the enemy was described by General Ross, as follows: "They were strongly posted on very commanding heights, formed in two lines, the advance occupying a fortified house, which with artillery covered the bridge over the Eastern Branch, across which the British troops had to pass. A broad and straight road, leading from the bridge to Washington, ran through the enemy's position, which was carefully defended by artillerymen and riflemen."374 Allowing for the tendency to magnify difficulties overcome, the British would have had before them a difficult task, if opposed by men accustomed to mutual support and mutual reliance, with the thousand-fold increase of strength which comes with such habit and with the moral confidence it gives.

The American line had been formed before Winder came on the ground. It extended across the Washington road as described by Ross. A battery on the hill-top commanded the bridge, and was supported by a line of infantry on either side, with a second line in the rear. Fearing, however, that the enemy might cross the stream higher up, where it was fordable in many places, a regiment from the second line was reluctantly ordered forward to extend the left; and Winder, when he arrived, while approving this disposition, carried thither also some of the artillery which he had brought with him.375 The anxiety of the Americans was therefore for their left. The British commander was eager to be done with his job, and to get back to his ships from a position militarily insecure. He had long been fighting Napoleon's troops in the Spanish peninsula, and was not yet fully imbued with Drummond's conviction that with American militia liberties might be taken beyond the limit of ordinary military precaution. No time was spent looking for a ford, but the troops dashed straight for the bridge. The fire of the American artillery was excellent, and mowed down the head of the column; but the seasoned men persisted and forced their way across. At this moment Barney was coming up with his seamen, and at Winder's request brought his guns into line across the Washington road, facing the bridge. Soon after this, a few rockets passing close over the heads of the battalions supporting the batteries on the left started them running, much as a mule train may be stampeded by a night alarm. It was impossible to rally them. A part held for a short time; but when Winder attempted to retire them a little way, from a fire which had begun to annoy them, they also broke and fled.376

The American left was thus routed, but Barney's battery and its supporting infantry still held their ground. "During this period," reported the Commodore,—that is, while his guns were being brought into battery, and the remainder of his seamen and marines posted to support them,—"the engagement continued, the enemy advancing, and our own army retreating before them, apparently in much disorder. At length the enemy made his appearance on the main road, in force, in front of my battery, and on seeing us made a halt. I reserved our fire. In a few minutes the enemy again advanced, when I ordered an 18-pounder to be fired, which completely cleared the road; shortly after, a second and a third attempt was made by the enemy to come forward, but all were destroyed. They then crossed into an open field and attempted to flank our right; he was met there by three 12-pounders, the marines under Captain Miller, and my men, acting as infantry, and again was totally cut up. By this time not a vestige of the American army remained, except a body of five or six hundred, posted on a height on my right, from whom I expected much support from their fine situation."377

In this expectation Barney was disappointed. The enemy desisted from direct attack and worked gradually round towards his right flank and rear. As they thus moved, the guns of course were turned towards them; but a charge being made up the hill by a force not exceeding half that of its defenders, they also "to my great mortification made no resistance, giving a fire or two, and retired. Our ammunition was expended, and unfortunately the drivers of my ammunition wagons had gone off in the general panic." Barney himself, being wounded and unable to escape from loss of blood, was left a prisoner. Two of his officers were killed, and two wounded. The survivors stuck to him till he ordered them off the ground. Ross and Cockburn were brought to him, and greeted him with a marked respect and politeness; and he reported that, during the stay of the British in Bladensburg, he was treated by all "like a brother," to use his own words.378

The character of this affair is sufficiently shown by the above outline narrative, re-enforced by the account of the losses sustained. Of the victors sixty-four were killed, one hundred and eighty-five wounded. The defeated, by the estimate of their superintending surgeon, had ten or twelve killed and forty wounded.379 Such a disparity of injury is usual when the defendants are behind fortifications; but in this case of an open field, and a river to be crossed by the assailants, the evident significance is that the party attacked did not wait to contest the ground, once the enemy had gained the bridge. After that, not only was the rout complete, but, save for Barney's tenacity, there was almost no attempt at resistance. Ten pieces of cannon remained in the hands of the British. "The rapid flight of the enemy," reported General Ross, "and his knowledge of the country, precluded the possibility of many prisoners being taken."380

That night the British entered Washington. The Capitol, White House, and several public buildings were burned by them; the navy yard and vessels by the American authorities. Ross, accustomed to European warfare, did not feel Drummond's easiness concerning his position, which technically was most insecure as regarded his communications. On the evening of June 25 he withdrew rapidly, and on that of the 26th regained touch with the fleet in the Patuxent, after a separation of only four days. Cockburn remarked in his official report that there was no molestation of their retreat; "not a single musket having been fired."381 It was the completion of the Administration's disgrace, unrelieved by any feature of credit save the gallant stand of Barney's four hundred.

The burning of Washington was the impressive culmination of the devastation to which the coast districts were everywhere exposed by the weakness of the country, while the battle of Bladensburg crowned the humiliation entailed upon the nation by the demagogic prejudices in favor of untrained patriotism, as supplying all defects for ordinary service in the field. In the defenders of Bladensburg was realized Jefferson's ideal of a citizen soldiery,382 unskilled, but strong in their love of home, flying to arms to oppose an invader; and they had every inspiring incentive to tenacity, for they, and they only, stood between the enemy and the centre and heart of national life. The position they occupied, though unfortified, had many natural advantages; while the enemy had to cross a river which, while in part fordable, was nevertheless an obstacle to rapid action, especially when confronted by the superior artillery the Americans had. The result has been told; but only when contrasted with the contemporary fight at Lundy's Lane is Bladensburg rightly appreciated. Occurring precisely a month apart, and with men of the same race, they illustrate exactly the difference in military value between crude material and finished product.

Coincident with the capture of Washington, a little British squadron—two frigates and five smaller vessels—ascended the Potomac. Fort Washington, a dozen miles below the capital, was abandoned August 27 by the officer in charge, removing the only obstacle due to the foresight of the Government. He was afterwards cashiered by sentence of court martial. On the 29th, Captain Gordon, the senior officer, anchored his force before Alexandria, of which he kept possession for three days. Upon withdrawing, he carried away all the merchantmen that were seaworthy, having loaded them with merchandise awaiting exportation. Energetic efforts were made by Captains Rodgers, Perry, and Porter, of the American Navy, to molest the enemy's retirement by such means as could be extemporized; but both ships and prizes escaped, the only loss being in life: seven killed and forty-five wounded.

After the burning of Washington, the British main fleet and army moved up the Chesapeake against Baltimore, which would undoubtedly have undergone the lot of Alexandria, in a contribution laid upon shipping and merchandise. The attack, however, was successfully met. The respite afforded by the expedition against Washington had been improved by the citizens to interpose earthworks on the hills before the city. This local precaution saved the place. In the field the militia behaved better than at Bladensburg, but showed, nevertheless, the unsteadiness of raw men. To harass the British advance a body of riflemen had been posted well forward, and a shot from these mortally wounded General Ross; but, "imagine my chagrin, when I perceived the whole corps falling back upon my main position, having too credulously listened to groundless information that the enemy was landing on Back River to cut them off."383

The British approached along the narrow strip of land between the Patapsco and Back rivers. The American general, Stricker, had judiciously selected for his line of defence a neck, where inlets from both streams narrowed the ground to half a mile. His flanks were thus protected, but the water on the left giving better indication of being fordable, the British directed there the weight of the assault. To meet this, Stricker drew up a regiment to the rear of his main line, and at right angles, the volleys from which should sweep the inlet. When the enemy's attack developed, this regiment "delivered one random fire," and then broke and fled; "totally forgetful of the honor of the brigade, and of its own reputation," to use Stricker's words.384 This flight carried along part of the left flank proper. The remainder of the line held for a time, and then retired without awaiting the hostile bayonet. The American report gives the impression of an orderly retreat; a British participant, who admits that the ground was well chosen, and that the line held until within twenty yards, wrote that after that he never witnessed a more complete rout. The invaders then approached the city, but upon viewing the works of defence, and learning that the fleet would not be able to co-operate, owing to vessels sunk across the channel, the commanding officer decided that success would not repay the loss necessary to achieve it. Fleet and army then withdrew.