Полная версия

Полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

The reasons for this abundance of force are evident. As regards commerce Great Britain was on the defensive; and the defensive cannot tell upon which of many exposed points a blow may fall. Dissemination of effort, however modified by strategic ingenuity, is thus to a certain extent imposed. If an American division might strike British trade on the equator between 20° and 30° west longitude, and also in the neighborhood of the Cape Verdes and of the Azores, preparation in some form to protect all those points was necessary, and they are too wide apart for this to be effected by mere concentration. So the blockade of the United States harbors. There might be in New York no American frigates, but if a division escaped from Boston it was possible it might come upon the New York blockade in superior force, if adequate numbers were not constantly kept there. The British commercial blockade, though offensive in essence, had also its defensive side, which compelled a certain dispersion of force, in order to be in local sufficiency in several quarters.

These several dispersed assemblages of British ships of war constituted the totality of naval effort imposed upon Great Britain by "the fourteen sail of vessels of all descriptions"216 which composed the United States navy. It would not in the least have been necessary had these been sloops of war—were they fourteen or forty. The weight of the burden was the heavy frigates, two of which together were more than a match for three of the same nominal class—the 38-gun frigate—which was the most numerous and efficient element in the British cruising force. The American forty-four was unknown to British experience, and could be met only by ships of the line. Add to this consideration the remoteness of the American shore, and its dangerous proximity to very vital British interests, and there are found the elements of the difficult problem presented to the Admiralty by the combination of American force—such as it was—with American advantage of position for dealing a severe blow to British welfare at the period, 1805-1812, when the empire was in the height of its unsupported and almost desperate struggle with Napoleon; when Prussia was chained, Austria paralyzed, and Russia in strict bonds of alliance—personal and political—with France.

If conditions were thus menacing, as we know them to to have been in 1812, when war was declared, and the invasion of Russia just beginning, when the United States navy was "fourteen pendants," what would they not have been in 1807, had the nation possessed even one half of the twenty ships of the line which Gouverneur Morris, a shrewd financier, estimated fifteen years before were within her competency? While entirely convinced of the illegality of the British measures, and feeling keenly—as what American even now cannot but feel?—the humiliation and outrage to which his country was at that period subjected, the writer has always recognized the stringent compulsion under which Great Britain lay, and the military wisdom, in his opinion, of the belligerent measures adopted by her to sustain her strength through that unparalleled struggle; while in the matter of impressment, it is impossible to deny—as was urged by Representative Gaston of North Carolina and Gouverneur Morris—that her claim to the service of her native seamen was consonant to the ideas of the time, as well as of utmost importance to her in that hour of dire need. Nevertheless, submission by America should have been impossible; and would have been avoidable if for the fourteen pendants there had been a dozen sail of the line, and frigates to match. To an adequate weighing of conditions there will be indeed resentment for impressment and the other mortifications; but it is drowned in wrath over the humiliating impotence of an administration which, owing to preconceived notions as to peace, made such endurance necessary. It is not always ignominious to suffer ignominy; but it always is so to deserve it.

President Washington, in his last annual message, December 7, 1796, defined the situation then confronting the United States, and indicated its appropriate remedy, in the calm and forcible terms which characterized all his perceptions. "It is in our own experience, that the most sincere neutrality is not a sufficient guard against the depredations of nations at war. To secure respect for a neutral flag requires a naval force, organized and ready, to vindicate it from insult or aggression. This may even prevent the necessity of going to war, by discouraging belligerent powers from committing such violations of the rights of the neutral party as may, first or last, leave no other option" [than war]. The last sentence is that of the statesman and soldier, who accurately appreciates the true office and sphere of arms in international relations. His successor, John Adams, yearly renewed his recommendation for the development of the navy; although, not being a military man, he seems to have looked rather exclusively on the defensive aspect, and not to have realized that possible enemies are more deterred by the fear of offensive action against themselves than by recognition of a defensive force which awaits attack at an enemy's pleasure. Moreover, in his administration, it was not Great Britain, but France, that was most actively engaged in violating the neutral rights of American shipping, and French commercial interests then presented nothing upon which retaliation could take effect. The American problem then was purely defensive,—to destroy the armed ships engaged in molesting the national commerce.

President Jefferson, whose influence was paramount with the dominant party which remained in power from his inauguration in 1801 to the war, based his policy upon the conviction, expressed in his inaugural, that this "was the only government where every man would meet invasions of the public order as his own personal concern;" and that "a well-disciplined militia is our best reliance for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them." In pursuance of these fundamental principles, it was doubtless logical to recommend in his first annual message that, "beyond the small force which will probably be wanted for actual service in the Mediterranean [against the Barbary pirates], whatever annual sum you may think proper to appropriate to naval preparations would perhaps be better employed in providing those articles which may be kept without waste or consumption, and be in readiness when any exigence calls them into use. Progress has been made in providing materials for seventy-four gun ships;" but this commended readiness issued in not laying their keels till after the war began.

Upon this first recommendation followed the discontinuance of building ships for ocean service, and the initiation of the gunboat policy; culminating, when war began, in the decision of the administration to lay up the ships built for war, to keep them out of British hands. The urgent remonstrances of two or three naval captains obtained the reversal of this resolve, and thereby procured for the country those few successes which, by a common trick of memory, have remained the characteristic feature of the War of 1812.

Note.—After writing the engagement between the "Boxer" and the "Enterprise," the author found among his memoranda, overlooked, the following statement from the report of her surviving lieutenant, David McCreery: "I feel it my duty to mention that the bulwarks of the 'Enterprise' were proof against our grape, when her musket balls penetrated through our bulwarks." (Canadian Archives, M. 389, 3. p. 87.) It will be noted that this does not apply to the cannon balls, and does not qualify the contrast in gunnery.

CHAPTER XIV

MARITIME OPERATIONS EXTERNAL TO THE WATERS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1813-1814

In broad generalization, based upon analysis of conditions, it has been said that the seacoast of the United States was in 1812 a defensive frontier, from which, as from all defensive lines, there should be, and was, opportunity for offensive returns; for action planned to relieve the shore-line, and the general military situation, by inflicting elsewhere upon the opponent injury, harassment, and perplexity. The last chapter dealt with the warfare depending upon the seaboard chiefly from the defensive point of view; to illustrate the difficulties, the blows, and the sufferings, to which the country was exposed, owing to inability to force the enemy away from any large portion of the coast. The pressure was as universal as it was inexorable and irresistible.

It remains still to consider the employment and effects of the one offensive maritime measure left open by the exigencies of the war; the cruises directed against the enemy's commerce, and the characteristic incidents to which they gave rise. In this pursuit were engaged both the national ships of war and those equipped by the enterprise of the mercantile community; but, as the operations were in their nature more consonant to the proper purpose of privateers, so the far greater number of these caused them to play a part much more considerable in effect, though proportionately less fruitful in conspicuous action. Fighting, when avoidable, is to the privateer a misdirection of energy. Profit is his object, by depredation upon the enemy's commerce; not the preservation of that of his own people. To the ship of war, on the other hand, protection of the national shipping is the primary concern; and for that reason it becomes her to shun no encounter by which she may hope to remove from the seas a hostile cruiser.

The limited success of the frigates in their attempts against British trade has been noted, and attributed to the general fact that their cruises were confined to the more open sea, upon the highways of commerce. These were now travelled by British ships under strict laws of convoy, the effect of which was not merely to protect the several flocks concentrated under their particular watchdogs, but to strip the sea of those isolated vessels, that in time of peace rise in irregular but frequent succession above the horizon, covering the face of the deep with a network of tracks. These solitary wayfarers were now to be found only as rare exceptions to the general rule, until the port of destination was approached. There the homing impulse overbore the bonds of regulation; and the convoys tended to the conduct noted by Nelson as a captain, "behaving as all convoys that ever I saw did, shamefully ill, parting company every day." Commodore John Rodgers has before been quoted, as observing that the British practice was to rely upon pressure on the enemy over sea, for security near home; and that the waters surrounding the British Islands themselves were the field where commerce destruction could be most decisively effected.

The first United States vessel to emphasize this fact was the brig "Argus," Captain William H. Allen, which sailed from New York June 18, 1813, having on board a newly appointed minister to France, Mr. William H. Crawford, recently a senator from Georgia. On July 11 she reached L'Orient, having in the twenty-three days of passage made but one prize.217 Three days later she proceeded to cruise in the chops of the English Channel, and against the local trade between Ireland and England; continuing thus until August 14, thirty-one days, during which she captured nineteen sail, extending her depredations well up into St. George's Channel. The contrast of results mentioned, between her voyage across and her occupancy of British waters, illustrates the comparative advantages of the two scenes of operations, regarded in their relation to British commerce.

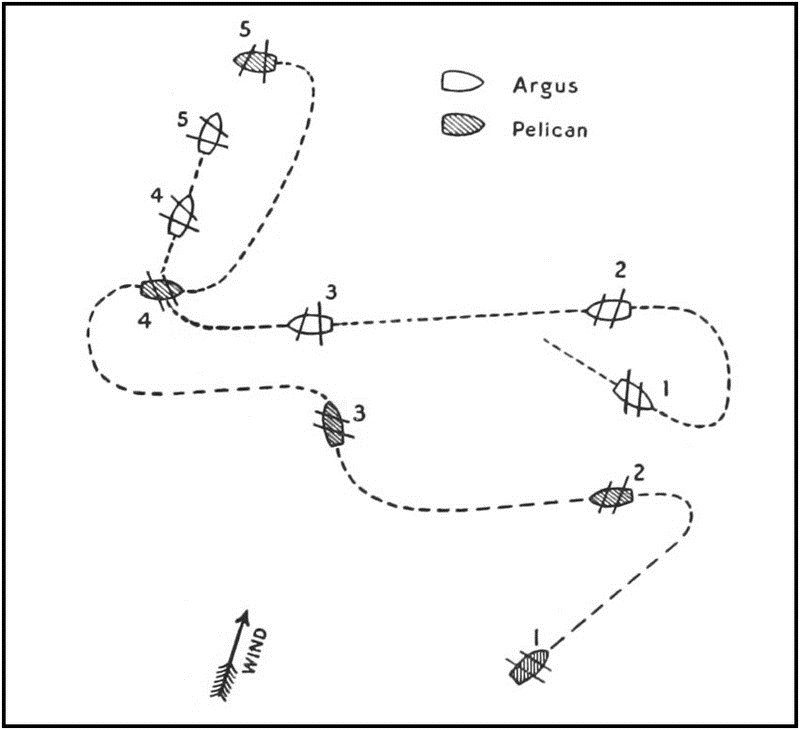

On August 12 the British brig of war "Pelican," Captain Maples, anchored at Cork from the West Indies. Before her sails were furled she received orders to go out in search of the American ship of war whose depredations had been reported. Two hours later she was again at sea. The following evening, at half-past seven, a burning vessel to the eastward gave direction to her course, and at daybreak, August 14, she sighted a brig of war in the northeast, just quitting another prize, which had also been fired. The wind, being south, gave the windward position to the "Pelican," which stood in pursuit; the "Argus" steering east, near the wind, but under moderate sail to enable her opponent to close (positions 1). The advantage in size and armament was on this occasion on the British side; the "Pelican" being twenty per cent larger, and her broadside seventeen per cent heavier.

At 5.55 A.M., St. David's Head on the coast of Wales bearing east, distant about fifteen miles, the "Argus" wore, standing now to the westward, with the wind on the port side (2). The "Pelican" did the same, and the battle opened at six; the vessels running side by side, within the range of grapeshot and musketry,—probably under two hundred yards apart (2). Within five minutes Captain Allen received a wound which cost him his leg, and in the end his life. He at first refused to be taken below, but loss of blood soon so reduced him that he could no longer exercise command. Ten minutes later the first lieutenant was stunned by the graze of a grapeshot along his head, and the charge of the ship devolved on the second. By this time the rigging of the "Argus" had been a good deal cut, and the "Pelican" bore up (3) to pass under her stern; but the American brig, luffing close to the wind and backing her maintopsail (3), balked the attempt, throwing herself across the enemy's path, and giving a raking broadside, the poor aim of which seems to have lost her the effect that should have resulted from this ready and neat manœuvre. The main braces of the "Argus" had already been shot away, as well as much of the other gear upon which the after sails depended; and at 6.18 the preventer (duplicate) braces, which formed part of the preparation for battle, were also severed. The vessel thus became unmanageable, falling off before the wind (4), and the "Pelican" was enabled to work round her at will. This she did, placing herself first under the stern (4), and then on the bow (5) of her antagonist, where the only reply to her broadside was with musketry.

In this helpless situation the "Argus" surrendered, after an engagement of a little over three quarters of an hour. The British loss was two killed and five wounded; the American, six killed and seventeen wounded, of whom five afterwards died. Among these was Captain Allen, who survived only four days, and was buried with military honors at Plymouth, whither Captain Maples sent his prize.218 After every allowance for disparity of force, the injury done by the American fire cannot be deemed satisfactory, and suggests the consideration whether the voyage to France under pressure of a diplomatic mission, and the busy preoccupation of making, manning, and firing prizes, during the brief month of Channel cruising, may not have interfered unduly with the more important requirements of fighting efficiency. The surviving officer in command mentions in explanation, "the superior size and metal of our opponent, and the fatigue which the crew of the 'Argus' underwent from a very rapid succession of prizes."

Diagram of the Argus vs. Pelican battle

From the broad outlook of the universal maritime situation, this rapid succession of captures is a matter of more significance than the loss of a single brig of war. It showed the vulnerable point of British trade and local intercommunication; and the career of the "Argus," prematurely cut short though it was, tended to fix attention upon facts sufficiently well known, but perhaps not fully appreciated. From this time the opportunities offered by the English Channel and adjacent waters, long familiar to French corsairs, were better understood by Americans; as was also the difficulty of adequately policing them against a number of swift and handy cruisers, preying upon merchant vessels comparatively slow, lumbering, and undermanned. The subsequent career of the United States ship "Wasp," and the audacious exploits of several privateers, recall the impunity of Paul Jones a generation before, and form a sequel to the brief prelude, in which the leading part, though ultimately disastrous, was played by the "Argus."

While the cruise of the "Argus" stood by no means alone at this time, the attending incidents made it conspicuous among several others of a like nature, on the same scene or close by; and it therefore may be taken as indicative of the changing character of the war, which soon began to be manifest, owing to the change of conditions in Europe. In general summary, the result was to transfer an additional weight of British naval operations to the American side of the Atlantic, which in turn compelled American cruisers, national and private, in pursuit of commerce destruction, to get away from their own shores, and to seek comparative security as well as richer prey in distant waters. To this contributed also the increasing stringency of British convoy regulation, enforced with special rigor in the Caribbean Sea and over the Western Atlantic. It was impossible to impose the same strict prescription upon the coastwise trade, by which chiefly the indispensable continuous intercourse between the several parts of the United Kingdom was maintained. Before the introduction of steam this had a consequence quite disproportionate to the interior traffic by land; and its development, combined with the feeling of greater security as the British Islands were approached, occasioned in the narrow seas, and on the coasts of Europe, a dispersion of vessels not to be seen elsewhere. This favored the depredations of the light, swift, and handy cruisers that alone are capable of profiting by such an opportunity, through their power to evade the numerous, but necessarily scattered, ships of war, which under these circumstances must patrol the sea, like a watchman on beat, as the best substitute for the more formal and regularized convoy protection, when that ceases to apply.

From the end of the summer of 1813, when this tendency to distant enterprise became predominant, to the corresponding season a year later, there were captured by American cruisers some six hundred and fifty British vessels, chiefly merchantmen; a number which had increased to between four and five hundred more, when the war ended in the following winter.219 An intelligible account of such multitudinous activities can be framed only by selecting amid the mass some illustrative particulars, accompanied by a general estimate of the conditions they indicate and the results they exemplify. Thus it may be stated, with fair approach to precision, that from September 30, 1813, to September 30, 1814, there were taken six hundred and thirty-nine British vessels, of which four hundred and twenty-four were in seas that may be called remote from the United States. From that time to the end of the war, about six months, the total captures were four hundred and fourteen, of which those distant were two hundred and ninety-three. These figures, larger actually and in impression than they are relatively to the total of British shipping, represent the offensive maritime action of the United States during the period in question; but, in considering them, it must be remembered that such results were possible only because the sea was kept open to British commerce by the paramount power of the British navy. This could not prevent all mishaps; but it reduced them, by the annihilation of hostile navies, to such a small percentage of the whole shipping movement, that the British mercantile community found steady profit both in foreign and coasting trade, of which the United States at the same time was almost totally deprived.

The numerous but beggarly array of American bay-craft and oyster boats, which were paraded to swell British prize lists, till there seemed to be a numerical set-off to their own losses, show indeed that in point of size and value of vessels taken there was no real comparison; but this was due to the fact, not at once suggested by the figures themselves, that there were but few American merchant vessels to be taken, because they did not dare to go to sea, with the exception of the few to whom exceptional speed gave a chance of immunity, not always realized. In the period under consideration, September, 1813, to September, 1814, despite the great falling off of trade noted in the returns, over thirty American merchant ships and letters of marque were captured at sea;220 at the head of the list being the "Ned," whose hair-breadth escapes in seeking to reach a United States port have been mentioned already.221 She met her fate near the French coast, September 6, 1813, on the outward voyage from New York to Bordeaux. Privateering, risky though it was, offered a more profitable employment, with less chance of capture; because, besides being better armed and manned, the ship was not impeded in her sailing by the carriage of a heavy cargo. While the enemy was losing a certain small proportion of vessels, the United States suffered practically an entire deprivation of external commerce; and her coasting trade was almost wholly suppressed, at the time that her cruisers, national and private, were causing exaggerated anxiety concerning the intercourse between Great Britain and Ireland, which, though certainly molested, was not seriously interrupted.

Further evidence of the control exerted by the British Navy, and of the consequent difficulty under which offensive action was maintained by the United States, is to be found in the practice, from this time largely followed, of destroying prizes, after removing from them packages of little weight compared to their price. The prospect of a captured vessel reaching an American port was very doubtful, for the same reason that prevented the movement of American commerce; and while the risk was sometimes run, it usually was with cargoes which were at once costly and bulky, such as West India goods, sugars and coffees. Even then specie, and light costly articles, were first removed to the cruiser, where the chances for escape were decidedly better. Recourse to burning to prevent recapture was permissible only with enemy's vessels. If a neutral were found carrying enemy's goods, a frequent incident of maritime war, she must be sent in for adjudication; which, if adverse, affected the cargo only. Summary processes, therefore, could not be applied in such cases, and the close blockade of the United States coast seriously restricted the operations of her cruisers in this particular field.

Examination of the records goes to show that, although individual American vessels sometimes made numerous seizures in rapid succession, they seldom, if ever, effected the capture or destruction of a large convoy at a single blow. This was the object with which Rodgers started on his first cruise, but failed to accomplish. A stroke of this kind is always possible, and he had combined conditions unusually favorable to his hopes; but, while history certainly presents a few instances of such achievement on the large scale, they are comparatively rare, and opportunity, when it offers, can be utilized only by a more numerous force than at any subsequent time gathered under the American flag. In 1813 two privateers, the "Scourge" of New York and "Rattlesnake" of Philadelphia, passed the summer in the North Sea, and there made a number of prizes,—twenty-two,—which being reported together gave the impression of a single lucky encounter; were supposed in fact to be the convoy for which Rodgers in the "President" had looked unsuccessfully the same season.222 The logs, however, showed that these captures were spread over a period of two months, and almost all made severally. Norway being then politically attached to Denmark, and hostile to Great Britain, such prizes as were not burned were sent into her ports. The "Scourge" appears to have been singularly fortunate, for on her homeward trip she took, sent in, or destroyed, ten more enemy's vessels; and in an absence extending a little over a year had taken four hundred and twenty prisoners,—more than the crew of a 38-gun frigate.223

At the same time the privateer schooner "Leo," of Baltimore, was similarly successful on the coast of Spain and Portugal. By an odd coincidence, another of the same class, bearing the nearly identical name, "Lion," was operating at the same time in the same waters, and with like results; which may possibly account for a contemporary report in a London paper, that an American off the Tagus had taken thirty-two British vessels. The "Leo" destroyed thirteen, and took four others; while the "Lion" destroyed fifteen, having first removed from them cargo to the amount of $400,000, which she carried safely into France. A curious circumstance, incidental to the presence of the privateers off Cape Finisterre, is that Wellington's troops, which had now passed the Pyrenees and were operating in southern France, had for a long time to wait for their great-coats, which had been stored in Lisbon for the summer, and now could not be returned by sea to Bayonne and Bordeaux before convoy was furnished to protect the transports against capture. Money to pay the troops, and for the commissariat, was similarly detained. Niles' Register, which followed carefully the news of maritime capture, announced in November, 1813, that eighty British vessels had been taken within a few months in European seas by the "President," "Argus," and five privateers. Compared with the continuous harassment and loss to which the enemy had become hardened during twenty years of war with France, allied often with other maritime states, this result, viewed singly, was not remarkable; but coming in addition to the other sufferings of British trade, and associated with similar injuries in the West Indies, and disquiet about the British seas themselves, the cumulative effect was undeniable, and found voice in public meetings, resolutions, and addresses to the Government.