Полная версия

Полная версияAdmiral Farragut

Serious action on the part of the army, directed by a man of whose vigorous character there could be no doubt, though his conspicuous ability was not yet fully recognized, was evidently at hand; and this circumstance, by itself alone, imparted a very different aspect to any naval enterprises, giving them reasonable prospect of support and of conducing substantially to the great common end. Never in the history of combined movements has there been more hearty co-operation between the army and navy than in the Vicksburg campaign of 1863, under the leadership of Grant and Porter. From the nature of the enemy's positions their forcible reduction was necessarily in the main the task of the land forces; but that the latter were able to exert their full strength, unweakened, and without anxiety as to their long line of communications from Memphis to Vicksburg, was due to the incessant vigilance and activity of the Mississippi flotilla, which grudged neither pains nor hard knocks to support every movement. But, besides the care of our own communications, there was the no less important service of harassing or breaking up those of the enemy. Of these, the most important was with the States west of the Mississippi. Not to speak of cereals and sugar, Texas alone, in the Southwest, produced an abundance of vigorous beef cattle fit for food; and from no other part of the seceded States could the armies on the east banks of the Mississippi be adequately supplied. Bordering, moreover, upon Mexico, and separated from it only by a shoal river into which the United States ships could not penetrate, there poured across that line quantities of munitions of war, which found through the Mexican port of Matamoras a safe entry, everywhere else closed to them by the sea-board blockade. For the transit of these the numerous streams west of the Mississippi, and especially the mighty Red River, offered peculiar facilities. The principal burden of breaking up these lines of supply was thrown upon the navy by the character of the scene of operations—by its numerous water-courses subsidiary to the great river itself, and by the overflow of the land, which, in its deluged condition during the winter, effectually prevented the movement of troops. Herein Farragut saw his opportunity, as well as that of the upper river flotilla. To wrest the control of the Mississippi out of the enemy's hands, by reducing his positions, was the great aim of the campaign; until that could be effected, the patrol of the section between Vicksburg and Port Hudson would materially conduce to the same end.

Over this Farragut pondered long and anxiously. He clearly recognized the advantage of this service, but he also knew the difficulties involved in maintaining his necessary communications, and, above all, his coal. At no time did the enemy cease their annoyance from the river banks. Constant brushes took place between their flying batteries and the different gunboats on patrol duty; a kind of guerrilla warfare, which did not cease even with the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, but naturally attained its greatest animation during the months when their fate was hanging in the balance. The gunboats could repel such attacks, though they were often roughly handled, and several valuable officers lost their lives; but not being able to pursue, the mere frustration of a particular attack did not help to break up a system of very great annoyance. Only a force able to follow—in other words, troops—could suppress the evil. "You will no doubt hear more," the admiral writes on the 1st of February, 1863, "of 'Why don't Farragut's fleet move up the river?' Tell them, Because the army is not ready. Farragut waits upon Banks as to when or where he will go."

Still, even while thus dancing attendance upon a somewhat dilatory general, his plans were maturing; so that when occasion arose he was, as always, ready for immediate action—had no unforeseen decision to make. "The evening of the day (about January 20th) that I reported to him at New Orleans," writes Admiral Jenkins, "he sent everybody out of the cabin, and said: 'I wish to have some confidential talk with you upon a subject which I have had in mind for a long time.... I have never hinted it to any one, nor does the department know anything of my thoughts. The first object to be accomplished, which led me to think seriously about it, is to cripple the Southern armies by cutting off their supplies from Texas. Texas at this time is, and must continue to the end of the war to be, their main dependence for beef cattle, sheep, and Indian corn. If we can get a few vessels above Port Hudson the thing will not be an entire failure, and I am pretty confident it can be done.'" Jenkins naturally suggested that the co-operation of the army by an active advance at the same time would materially assist the attempt. To this, of course, the admiral assented, it being in entire conformity with his own opinion; and several interviews were held, without, however, their leading to any definite promise on the part of General Banks.

Meantime Admiral Porter, who after leaving the mortar flotilla had been appointed to the command of the Mississippi squadron, with the rank of acting rear-admiral, realized as forcibly as Farragut the importance of placing vessels in the waters between Vicksburg and Port Hudson. In the middle of December he was before Vicksburg, and had since then been actively supporting the various undertakings of the land forces. Three days after Grant joined the army, on the 2d of February, the ram Queen of the West ran the Vicksburg batteries from above, and successfully reached the river below. Ten days later, Porter sent on one of his newest ironclads, the Indianola, which made the same passage under cover of night without being even hit, although twenty minutes under fire. The latter vessel took with her two coal barges; and as the experiment had already been successfully tried of casting coal barges loose above the batteries, and trusting to the current to carry them down to the Queen of the West, the question of supplies was looked upon as settled. The Indianola was very heavily armed, and both the admiral and her commander thought her capable of meeting any force the enemy could send against her.

Unfortunately, on the 14th of February, two days only after the Indianola got down, the Queen of the West was run ashore under a battery and allowed to fall alive into the hands of the enemy. The latter at once repaired the prize, and, when ready, started in pursuit of the Indianola with it and two other steamers; one of which was a ram, the other a cotton-protected boat filled with riflemen. There was also with them a tender, which does not appear to have taken part in the fight. On the night of February 24th the pursuers overtook the Indianola, and a sharp action ensued; but the strength of the current and her own unwieldiness placed the United States vessel at a disadvantage, which her superior armament did not, in the dim light, counterbalance. She was rammed six or seven times, and, being then in a sinking condition, her commander ran her on the bank and surrendered. This put an end to Porter's attempts to secure that part of the river by a detachment. The prospect, that had been fair enough when the Queen of the West was sent down, was much marred by the loss of that vessel; and the subsequent capture of the Indianola transferred so much power into the hands of the Confederates, that control could only be contested by a force which he could not then afford to risk.

The up-river squadron having failed to secure the coveted command of the river, and, besides, transferred to the enemy two vessels which might become very formidable, Farragut felt that the time had come when he not only might but ought to move. He was growing more and more restless, more and more discontented with his own inactivity, when such an important work was waiting to be done. The news of the Queen of the West's capture made him still more uneasy; but when that was followed by the loss of the Indianola, his decision was taken at once. "The time has come," he said to Captain Jenkins; "there can be no more delay. I must go—army or no army." Another appeal, however, was made to Banks, representing the assistance which the squadron would derive in its attempt to pass the batteries from a demonstration made by the army. The permanent works at Port Hudson then mounted nineteen heavy cannon, many of them rifled; but there were reported to be in addition as many as thirty-five field-pieces, which, at the distance the fleet would have to pass, would be very effective. If the army made a serious diversion in the rear, many of these would be withdrawn, especially if Farragut's purpose to run by did not transpire. The advantage to be gained by this naval enterprise was so manifest that the general could scarcely refuse, and he promised to make the required demonstration with eight or ten thousand troops.

On the 12th of March, within a fortnight after hearing of the Indianola affair, Farragut was off Baton Rouge. On the 14th he anchored just above Profit's Island, seven miles below Port Hudson, where were already assembled a number of the mortar schooners, under the protection of the ironclad Essex, formerly of the upper squadron. The admiral brought with him seven vessels, for the most part essentially fighting ships, unfitted for blockade duty by their indifferent speed, but carrying heavy batteries. If the greater part got by, they would present a force calculated to clear the river of every hostile steamer and absolutely prevent any considerable amount of supplies being transferred from one shore to the other.

For the purpose of this passage Farragut adopted a somewhat novel tactical arrangement, which he again used at Mobile, and which presents particular advantages when there are enemies only on one side to be engaged. Three of his vessels were screw steamers of heavy tonnage and battery; three others comparatively light. He directed, therefore, that each of the former should take one of the latter on the side opposite to the enemy, securing her well aft, in order to have as many guns as possible, on the unengaged side, free for use in case of necessity. In this way the smaller vessels were protected without sacrificing the offensive power of the larger. Not only so; in case of injury to the boilers or engines of one, it was hoped that those of her consort might pull her through. To equalize conditions, to the slowest of the big ships was given the most powerful of the smaller ones. A further advantage was obtained in this fight, as at Mobile, from this arrangement of the vessels in pairs, which will be mentioned at the time of its occurrence. The seventh ship at Port Hudson, the Mississippi, was a very large side-wheel steamer. On account of the inconvenience presented by the guards of her wheel-houses, she was chosen as the odd one to whom no consort was assigned.

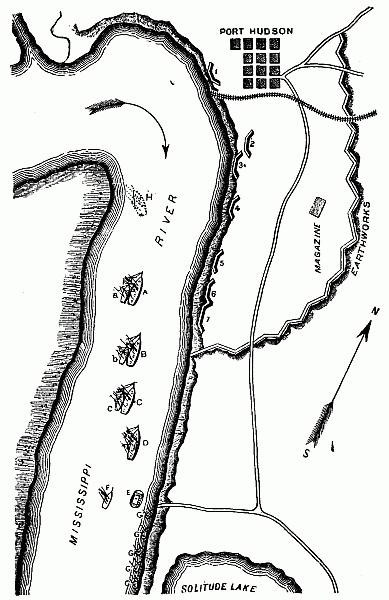

Order of Attack on Batteries at Port Hudson, March 14, 1863.

A. Hartford (flag-ship), Captain James S. Palmer. a. Albatross, Lieut.-Com. John E. Hart. B. Richmond, Commander James Alden. b. Genesee, Commander W. H. Macomb. C. Monongahela, Captain J. P. McKinstry. c. Kineo, Lieut.-Com. John Waters. D. Mississippi, Captain Melancton Smith. E. Essex, Commander C. H. B. Caldwell. F. Sachem, Act. Vol. Lieut. Amos Johnson. G. G. Mortar schooners. H. Spot where Mississippi grounded.

Going up the river toward Port Hudson the course is nearly north; then a bend is reached of over ninety degrees, so that after making the turn the course for some distance is west-southwest. The town is on the east side, just below the bend. From it the batteries extended a mile and a half down the river, upon bluffs from eighty to a hundred feet high. Between the two reaches, and opposite to the town, is a low, narrow point, from which a very dangerous shoal makes out. The channel runs close to the east bank.

The squadron remained at its anchorage above Profit's Island but a few hours, waiting for the cover of night. Shortly before 10 p. m. it got under way, ranged as follows: Hartford, Richmond, Monongahela, each with her consort lashed alongside, the Mississippi bringing up the rear. Just as they were fairly starting a steamer was seen approaching from down the river, flaring lights and making the loud puffing of the high-pressure engines. The flag-ship slowed down, and the new arrival came alongside with a message from the general that the army was then encamped about five miles in rear of the Port Hudson batteries. Irritated by a delay, which served only to attract the enemy's attention and to assure himself that no diversion was to be expected from the army, the admiral was heard to mutter: "He had as well be in New Orleans or at Baton Rouge for all the good he is doing us." At the same moment the east bank of the river was lit up, and on the opposite point huge bonfires kindled to illumine the scene—a wise precaution, the neglect of which by the enemy had much favored the fleet in the passage of the lower forts.

The ships now moved on steadily, but very slowly, owing to the force of the current. At 11 p. m. the Hartford had already passed the lower batteries, when the enemy threw up rockets and opened fire. This was returned not only by the advancing ships, but also by the ironclad Essex and the mortar schooners, which had been stationed to cover the passage. The night was calm and damp, and the cannonade soon raised a dense smoke which settled heavily upon the water, covering the ships from sight, but embarrassing their movements far more than it disconcerted the aim of their opponents. The flag-ship, being in the advance, drew somewhat ahead of the smoke, although even she had from time to time to stop firing to enable the pilot to see. Her movements were also facilitated by placing the pilot in the mizzen-top, with a speaking tube to communicate with the deck, a precaution to which the admiral largely attributed her safety; but the vessels in the rear found it impossible to see, and groped blindly, feeling their way after their leader. Had the course to be traversed been a straight line, the difficulty would have been much less; but to make so sharp a turn as awaited them at the bend was no easy feat under the prevailing obscurity. As the Hartford attempted it the downward current caught her on the port bow, swung her head round toward the batteries, and nearly threw her on shore, her stem touching for a moment. The combined powers of her own engine and that of the Albatross, her consort, were then brought into play as an oarsman uses the oars to turn his boat, pulling one and backing the other; that of the Albatross was backed, while that of the Hartford went ahead strong. In this way their heads were pointed up stream and they went through clear; but they were the only ones who effected the passage.

The Richmond, which followed next, had reached the bend and was about to turn when a plunging shot upset both safety valves, allowing so much steam to escape that the engines could not be efficiently worked. Thinking that the Genesee, her companion, could not alone pull the two vessels by, the captain of the Richmond turned and carried them both down stream. The Monongahela, third in the line, ran on the shoal opposite to the town with so much violence that the gunboat Kineo, alongside of her, tore loose from the fastenings. The Monongahela remained aground for twenty-five minutes, when the Kineo succeeded in getting her off. She then attempted again to run the batteries, but when near the turn a crank-pin became heated and the engines stopped. Being now unmanageable, she drifted down stream and out of action, having lost six killed and twenty-one wounded. The Mississippi also struck on the shoal, close to the bend, when she was going very fast, and defied every effort to get her off. After working for thirty-five minutes, finding that the other ships had passed off the scene leaving her unsupported, while three batteries had her range and were hulling her constantly, the commanding officer ordered her to be set on fire. The three boats that alone were left capable of floating were used to land the crew on the west bank; the sick and wounded being first taken, the captain and first lieutenant leaving the ship last. She remained aground and in flames until three in the morning, when she floated and drifted down stream, fortunately going clear of the vessels below. At half-past five she blew up. Out of a ship's company of two hundred and ninety-seven, sixty-four were found missing, of whom twenty-five were believed to be killed.

In his dispatch to the Navy Department, written the second day after this affair, the admiral lamented that he had again to report disaster to a part of his command. A disaster indeed it was, but not of the kind which he had lately had to communicate, and to which the word "again" seems to refer; for there was no discredit attending it. The stern resolution with which the Hartford herself was handled, and the steadiness with which she and her companion were wrenched out of the very jaws of destruction, offer a consummate example of professional conduct; while the fate of the Mississippi, deplorable as the loss of so fine a vessel was, gave rise to a display of that coolness and efficiency in the face of imminent danger which illustrate the annals of a navy as nobly as do the most successful deeds of heroism.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that the failure to pass the batteries, by nearly three fourths of the force which the admiral had thought necessary to take with him, constituted a very serious check to the operations he had projected. From Port Hudson to Vicksburg is over two hundred miles; and while the two ships he still had were sufficient to blockade the mouth of the Red River—the chief line by which supplies reached the enemy—they could not maintain over the entire district the watchfulness necessary wholly to intercept communication between the two shores. Neither could they for the briefest period abandon their station at the river's mouth, without affording an opportunity to the enemy; who was rendered vigilant by urgent necessities which forced him to seize every opening for the passage of stores. From the repulse of five out of the seven ships detailed for the control of the river, it resulted that the enemy's communications, on a line absolutely vital to him, and consequently of supreme strategic importance, were impeded only, not broken off. It becomes, therefore, of interest to inquire whether this failure can be attributed to any oversight or mistake in the arrangements made for forcing the passage—in the tactical dispositions, to use the technical phrase. In this, as in every case, those dispositions should be conformed to the object to be attained and to the obstacles which must be overcome.

The purpose which the admiral had in view was clearly stated in the general order issued to his captains: "The captains will bear in mind that the object is to run the batteries at the least possible damage to our ships, and thereby secure an efficient force above, for the purpose of rendering such assistance as may be required of us to the army at Vicksburg, or, if not required there, to our army at Baton Rouge." Such was the object, and the obstacles to its accomplishment were twofold, viz., those arising from the difficulties of the navigation, and those due to the preparations of the enemy. To overcome them, it was necessary to provide a sufficient force, and to dispose that force in the manner best calculated to insure the passage, as well as to entail the least exposure. Exposure is measured by three principal elements—the size and character of the target offered, the length of time under fire, and the power of the enemy's guns; and the last, again, depends not merely upon the number and size of the guns, but also upon the fire with which they are met. In this same general order Farragut enunciated, in terse and vigorous terms, a leading principle in warfare, which there is now a tendency to undervalue, in the struggle to multiply gun-shields and other defensive contrivances. It is with no wish to disparage defensive preparations, nor to ignore that ships must be able to bear as well as to give hard knocks, that this phrase of Farragut's, embodying the experience of war in all ages and the practice of all great captains, is here recalled, "The best protection against the enemy's fire is a well-directed fire from our own guns."

The disposition adopted for the squadron was chiefly a development of this simple principle, combined with an attempt to form the ships in such an order as should offer the least favorable target to the enemy. A double column of ships, if it presents to the enemy a battery formidable enough to subdue his fire, in whole or in part, shows a smaller target than the same number disposed in a single column; because the latter order will be twice as long in passing, with no greater display of gun-power at a particular point. The closer the two columns are together, the less chance there is that a shot flying over the nearer ship will strike one abreast her; therefore, when the two are lashed side by side this risk is least, and at the same time the near ship protects the off one from the projectile that strikes herself. These remarks would apply, in degree, if all the ships of the squadron had had powerful batteries; the limitation being only that enough guns must be in the near or fighting column to support each other, and to prevent several of the enemy's batteries being concentrated on a single ship—a contingency dependent upon the length of the line of hostile guns to be passed. But when, as at Port Hudson, several of the vessels are of feeble gun-power, so that their presence in the fighting column would not re-enforce its fire to an extent at all proportionate to the risk to themselves, the arrangement there adopted is doubly efficacious.

The dispositions to meet and overcome the difficulties imposed by the enemy's guns amounted, therefore, to concentrating upon them the batteries of the heavy ships, supporting each other, and at the same time covering the passage of a second column of gunboats, which was placed in the most favorable position for escaping injury. In principle the plan was the same as at New Orleans—the heavy ships fought while the light were to slip by; but in application, the circumstances at the lower forts would not allow one battery to be masked as at Port Hudson, because there were enemy's works on both sides. For meeting the difficulties of the navigation on this occasion, Farragut seems not to have been pleased with the arrangement adopted. "With the exception of the assistance they might have rendered the ships, if disabled, they were a great disadvantage," he wrote. The exception, however, is weighty; and, taken in connection with his subsequent use of the same order at Mobile, it may be presumed the sentence quoted was written under the momentary recollection of some inconvenience attending this passage. Certainly, with single-screw vessels, as were all his fleet, it was an inestimable advantage, in intricate navigation or in close quarters, to have the help of a second screw working in opposition to the first, to throw the ship round at a critical instant. In the supreme moment of his military life, at Mobile, he had reason to appreciate this advantage, which he there, as here, most intelligently used.

Thus analyzed, there is found no ground for adverse criticism in the tactical dispositions made by Farragut on this memorable occasion. The strong points of his force were utilized and properly combined for mutual support, and for the covering of the weaker elements, which received all the protection possible to give them. Minor matters of detail were well thought out, such as the assignment to the more powerful ship of the weaker gunboat, and the position in which the small vessels were to be secured alongside. The motto that "the best protection against the enemy's fire is a well-directed fire by our own guns" was in itself an epitome of the art of war; and in pursuance of it the fires of the mortar schooners and of the Essex were carefully combined by the admiral with that of the squadron. Commander Caldwell, of the Essex, an exceedingly cool and intelligent officer, reported that "the effect of the mortar fire (two hundred bombs being thrown in one hundred and fifty minutes, from eleven to half-past one) seemed to be to paralyze the efforts of the enemy at the lower batteries; and we observed that their fire was quite feeble compared to that of the upper batteries." Nor had the admiral fallen into the mistake of many general officers, in trusting too lightly to the comprehension of his orders by his subordinates. Appreciating at once the high importance of the object he sought to compass, and the very serious difficulties arising from the enemy's position at Port Hudson and the character of the navigation, he had personally inspected the ships of his command the day before the action, and satisfied himself that the proper arrangements had been made for battle. His general order had already been given to each commanding officer, and he adds: "We conversed freely as to the arrangements, and I found that all my instructions were well understood and, I believe, concurred in by all. After a free interchange of opinions on the subject, every commander arranged his ship in accordance with his own ideas."