Полная версия

Полная версияSocial Environment and Moral Progress

Such facts exist all over the kingdom. They have been talked about and deplored for the last half-century at least. Who has murdered the 100,000 children who die annually before they are one year old? Who has robbed the millions that just survive of all that makes childhood happy—pure food, fresh air, play, rest, sleep, and proper nurture and teaching? Again we must answer, our Parliament, which occupies itself with anything rather than the immediate saving of human life and abolishing widespread human misery, the whole of which is remediable. And all for fear of offending the rich and powerful by some diminution of their ever-increasing accumulations of wealth. No thinking man or woman can believe that this state of things is absolutely irremediable; and the persistent acquiescence in it while loudly boasting of our civilisation, of our science, of our national prosperity, and of our Christianity, is the proof of a hypocritical lack of national morality that has never been surpassed in any former age.

A new set of evils has grown up in the various so-called "unhealthy trades"—the lead glaze in the china manufacture, the steel dust in cutlery work, and the endless variety of poisonous liquids and vapours in the numerous chemical works or processes, by which so many fortunes have been made. These, together, are the cause of a large direct loss of life, and a much larger amount of permanent injury, together with a terrible reduction in the duration of life of all the workers in such trades. Yet in one case only—that of phosphorus matches—has any such injurious process of manufacture been put an end to. Wealth has been deliberately preferred to human life and happiness.4

One of the most deadly of trades seems to have remained unnoticed till it has been brought to light by the new Labour paper, The Daily Citizen, in a series of articles by Mr. Keighley Snowden, entitled The Broken Women. Never was a title better deserved, since large numbers of girls and young women are employed at Lye and Cradley Heath, in what is commonly named the "Hollow Ware" works. This is the tinning, or galvanising, as it is usually termed, of buckets and other domestic utensils, in which lead is used; and it produces one of the most virulent forms of lead-poisoning. The symptoms are, among other more painful ones, the loss of hair and the loosening and ultimate loss of teeth, culminating either in chronic illness or death, sometimes in a few months or years. Five years ago there was a Home Office inquiry, which, after full examination, reported that the process used was dangerous to life, that no precautions could render it harmless, and that it should be totally discontinued.

An order was then issued by the Home Office that after a time-limit (two years) the process should be no longer used; but that order has not been obeyed (except by a few employers) to this day. The deadly nature of this work was accompanied by miserably low wages, as shown by the fact that the women workers have at length struck to obtain a minimum of 10s. a week! Helped by some humane friends, they have at length succeeded in obtaining this miserable wage, and for the present are in a state of comparative happiness! How long it will be before the Government abolishes this deadly process we cannot tell. The following is a brief statement of what these poor women have to suffer, extracted from The Daily Citizen of November 20th, 1912:—

"They had, without power to resist them, suffered repeated and ruthless reductions of wages. They had seen their industry brought down by reckless competition, and the manufacture of shoddy goods, to the point at which men could no longer earn enough to support their families. They had seen their wives and daughters and boys forced by want at home into workshops, where, as official inquiry has shown, health was sucked out of their bodies as though they had been the victims of vampires. They had seen the introduction and growth of the sub-contracting 'stint' system, under which boyhood and girlhood and motherhood were driven as though they had been slaves under the lash, and their earnings cut down to a penny an hour. Meanwhile, they lived in the hovels and holes of a place which can only be fitly described as one of the dirtiest ashpits of a civilisation reckless of dirt where profit is a question."

Those who want to know what horrors can exist to-day in England should read Mr. Snowden's series of articles on the subject. They are restrained in language, and state the bare facts from careful personal observation. That such things should still exist in a country claiming to be civilised would be incredible, were there not so many others of a like nature and almost as bad.

In an almost exhaustive volume on Diseases of Occupation by Sir Thomas Oliver, M.D. (1908), there is only a short reference to the hollowware trade of the "black country" near Birmingham. But the tin plate industry of South Wales is more fully described, with the same pitiable condition of the women workers and the same terrible results to health and life. Yet nothing whatever seems to be done by the manufacturers; and though two Home Office Inspectors have fully reported on its horrors from 1888 onwards, no notice appears to have been taken of them, nor has there been any Government interference with conditions of labour which are a disgrace to civilisation.

CHAPTER X

ADULTERATION, BRIBERY, AND GAMBLING

After the terrible national crime of deadly employments it is almost an anti-climax to enumerate the vast mass of dishonesty and falsehood that pervades our commercial system in every department. Almost every fabric, whether of cotton, linen, wool, or silk, is so widely and ingeniously adulterated by the intermixture of cheaper materials that the pure article as supplied to our grandparents is hardly to be obtained. Of this one example only must serve. Calicoes have been successively dressed with such substances as paste and tallow; then with the still cheaper china clay and size; and in some cases from 50 to 90 per cent. of these latter materials have been sold as calico for exportation to countries inhabited by what we term savages. These people only found out the deception when the need for washing or exposure to tropical rains reduced the material to a flimsy and worthless rag, as I have myself witnessed in some parts of the Malay Archipelago.5

Even worse is the adulteration of almost every kind of prepared food—including the showy sweetmeats which tempt our children—with various chemicals, which are often injurious to health, and sometimes fatal; while even the drugs we take in the endeavour to cure our various ailments are frequently so treated as to be useless or even hurtful. Along with this form of dishonesty is what may be termed simple cheating in the description of goods sold, especially as to quantity. Threads and fabrics are generally shorter or narrower than stated, giving a larger profit when sold in enormous quantities in our great retail shops.

Then, again, there is a widespread system of bribery of servants or other employees in order to obtain more customers or to secure contracts; and though these are all criminal offences, and a great host of inspectors and official analysts are employed to discover and convict the offenders, yet so few people are willing to take the trouble and lose the time and money involved in putting the law into motion, that a very large percentage of these offences go undiscovered and unpunished.

Yet another and more serious form of plunder of the public is carried on by means of Joint Stock Companies, of which there are now more than 50,000 in England and Wales. In the year 1911 the number of new companies was 5,959, while 4,353 ceased to exist, giving an increase of 1,606 in the year. The Limited Liability Act was passed in 1855, in order that the public might invest their savings in companies, and thus share in the profits of our industry and commerce. It was supposed to be quite proper that anyone should benefit by the enterprise and industry of others; but to do so is essentially immoral, and has resulted in a vast system of swindling and terrible losses to the innocent investors. The promoters, directors, secretaries and bankers of these companies always gain; those that take up the shares often lose; and the amount of misery and absolute ruin of those who fondly hoped to add to their scanty incomes, and have been deluded by the names of well-known public men among the directors, is incalculable.

Our Stock Exchanges, too, are used largely for pure gambling which, owing to its vast extent and being carried on under business forms, is perhaps more ruinous than any other. But this form of gambling goes on unchecked, and is generally accepted as quite honest business. Yet ordinary betting on races and other forms of direct gambling are hypocritically condemned as immoral and criminal.

The vast fabric of our Foreign Trade in food, or the raw materials of our manufactures, is also used to support perhaps the greatest system of gambling the world has ever seen. The fluctuating prices of corn or cotton, of coal or mineral oil, of iron and other metals, in the great markets of the world, are used in two ways by a large community of gamblers, who not only do not require the goods they buy, but who never see nor possess them. The ordinary speculator who buys when prices are low, to sell again at a profit, without himself being able to influence the rise or fall of price, is a pure gambler who thinks he can foresee the changes of the market price in the immediate future. But the great capitalists who, either singly or by means of what are called rings or combines, purchase such vast quantities of the special product as to create a scarcity in the market, leading to a large rise of price, are ingenious robbers rather than gamblers, because, by clever dealings with such a monopoly, often aided by false rumours widely circulated in newspapers owned or bribed by them, they are able to make enormous profits at the expense of those who are obliged to purchase for actual business purposes or for daily use. This is one of the methods by which the great millionaires and multi-millionaires of the world accumulate their wealth, every penny of which is at the cost of the consuming public.

This is certainly as immoral as any of the petty forms of swindling with marked cards, loaded dice, or the wilful losing of a race; yet the possessors of such wealth are usually held to be clever business men, whose morality is not questioned.

All these inconsistencies as regards the moral status of various kinds of gambling or dishonest speculation arise from our inveterate habit of dealing with limited cases, each judged on its supposed merits as to consequences, instead of looking to fundamental principles. Why is gambling immoral? Not because it is a game of chance, entered into for mere amusement, even when played for small money stakes which are of no importance to any of the players. The fundamental wrong arises whenever it is used for obtaining wealth or any part of the player's income; and the reason is, that whatever one wins, someone else loses; while its evil nature, socially, depends upon the fact that whoever acquires wealth by such means contributes nothing useful to the social organism of which he forms a part. If it were taught to every child, and in every school and college, that it is morally wrong for anyone to live upon the combined labour of his fellow-men without contributing an approximately equal amount of useful labour, whether physical or mental, in return, all kinds of gambling, as well as many other kinds of useless occupation, would be seen to be of the same nature as direct dishonesty or fraud, and, therefore, would soon come to be considered disgraceful as well as immoral.

We see, then, that the whole commercial fabric of our country—our immense mills and factories, our vast exports and imports, our home trade, wholesale and retail, and innumerable transactions in our Stock Exchanges—is permeated with various forms of dishonesty, gambling, and direct robbery of individuals or of the public. No class is wholly free from it, and it increases in volume from decade to decade, just as our boasted commerce and accumulated wealth increases.

I have here called attention to these various forms of immoral practices because they are so often ignored. Yet they are all officially admitted by the enormous mass of the various Royal Commissions, Parliamentary and other Reports, as well as by the hundreds of "Acts" by which successive Parliaments have endeavoured to deal with them, but which have, one and all, proved to be either wholly or partially ineffective. The reason of this failure is that in every case symptoms and isolated results only have been considered, while the underlying causes of the whole vast mass of social corruption have never been sought for, or, if known, have never influenced legislation.

CHAPTER XI

OUR ADMINISTRATION OF "JUSTICE" IS IMMORAL

When we read about the Turkish or other Eastern law courts, in which direct bribery of every official up to the judge himself is a regular feature, we are horrified, and are apt to proclaim the fact that our judges never take bribes. But, practically, it comes to very nearly the same thing in England. No single step can be made for the purpose of getting justice without paying fees; while the whole process of bringing or defending an action-at-law is so absurdly complex as to be almost incredible. Jeremy Bentham satirised this by supposing a father of a large family to adopt the same method of settling a dispute between two of his sons. He would not hear either of them himself, but each must tell his story to a stranger (a solicitor), who wrote it down and then instructed another stranger (a barrister) to explain it to the father (as judge) and twelve neighbours (the jury). Then the stranger (barrister) on each side asked questions of all the family who knew anything about it; and the barristers, who had only third-hand knowledge of the facts, tried to make each witness contradict himself, or to acknowledge having done something as bad another time; till the jury became quite puzzled, and often decided as the cleverest of the barristers told them.

That is really the system of law courts to this day; and it is grossly unfair, because the party who can pay the highest fees for the services of the most experienced counsel is most likely, through the lawyer's skill and eloquence, to secure a verdict in his favour. Yet there is no effective protest against this unjust and absurd system, which absolutely denies all redress of wrongs to the poor man when oppressed by a rich one. One would think it self-evident that justice ceases to be justice when it has to be paid for. But the system is so time-hallowed, the profession of a barrister so honoured, and its rewards so great, that it will never be abolished till there comes about in our social system that fundamental change which will cut at the very root-cause of almost all our existing law-suits, immorality and crime.

In our criminal as well as our civil law and procedure there is equal injustice. When the poor man is accused of the slightest offence and brought before a magistrate by the police, he is, even though perfectly honest and respectable, treated from the very first as if he were guilty, often refused communication with his friends; and, when the accusation is serious, he is remanded to prison again and again till evidence has been hunted up, or even manufactured, against him. Experience shows that the latter is often done and a quite innocent man not infrequently punished. The dictum of the law, that an Englishman should be held to be innocent till he is proved to be guilty, is absolutely reversed, and he is treated as if he were guilty till, against overwhelming odds, he is able to prove himself innocent. There is no possible excuse for this now, and at the very least every man who has a home or a permanent employment should be at once discharged on his own recognizances.

Equally unjust and barbarous is the system of money-fines, often for merely nominal offences, with the alternative of imprisonment. To the well-off, or to the habitual criminal, the fine is a trifle; but to the poor man charged with being drunk, with begging, or with sleeping under a haystack, or any such act which is no real offence, the common punishment of 10s. or a week's imprisonment, leaving perhaps wife and children to starve or be sent to the workhouse, is really far more immoral than the alleged offence.

Again, our Poor Law itself, as usually administered, is utterly immoral. This is what a competent authority—Mr. Sidney Webb—says of it:

"Underneath the feet of the whole wage-earning class is the abyss of the Poor Law. I see before me a respectable family applying for relief. What do we do to them? We, the Government of England, break up the family. We strip each individual of what makes life worth living. When the man enters the workhouse he is stripped of his citizenship—branded as too infamous to vote for a member of Parliament. Once in the workhouse, we put him to toil or to loiter under conditions that are so demoralising that we turn him into a wastrel. And we strip the wife of her children. We send her to the wash-tub or the sewing-room, where she associates with prostitutes and imbeciles. The little children, if they are under five, are taken to the workhouse nursery, where they also are tended by prostitutes and imbeciles. There they remain, day after day, without ever going down the workhouse steps until they are old enough to go to the Poor Law school, or until they are taken down in their coffins, owing to the terrible mortality among the workhouse babies."

Of course, all workhouses are not so bad as this, but many are, and have been during the three-quarters of a century of their existence. Can we, therefore, wonder that week by week some poor and honest parents commit suicide rather than see their children starve, or be separated from them in the workhouse! The people we thus drive to death are many of them as good as we ourselves are; yet the "Guardians of the Poor"—well-to-do gentlemen and ladies—go on administering it week after week and year after year without protest or apparent compunction. Such is the deadening effect of long-continued custom.

CHAPTER XII

INDICATIONS OF INCREASING MORAL DEGRADATION

There are in the Reports of the Registrar-General a few statistics of special importance because they clearly point to certain kinds of moral degradation which have been increasing for the last half-century, thus coinciding with our exceptionally rapid increase in wealth; and also, as I have shown in preceding chapters, with various forms of national, economic, and social deterioration.

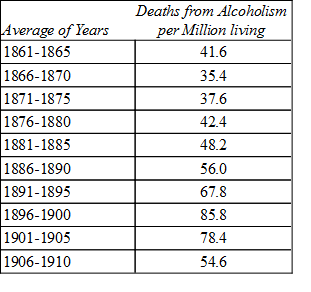

The first of these is the continuous increase in deaths from alcoholism, in proportion to population, since the year 1861. Most persons will be amazed to find that this is the case, because the drinking habit has certainly diminished; but when the habit becomes so powerful and lasts so long as to be the direct cause of death, we are able to see the dimensions of the most exaggerated form of the drink evil. The following figures are taken from the successive Reports referred to:—

There are some irregularities, the ratio being nearly equal for the first twenty years, after which there is such a continuous large increase that from 1876-80 to 1896-1900 the mortality is doubled, but for the last ten years there has been a decrease, which in the last five years is very marked.

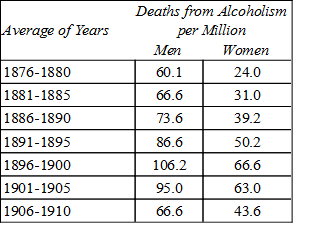

But a still worse and more disquieting feature is the recent large increase of mortality from alcoholism in women. Figures for the separate sexes were not given till 1876, and the following table shows the comparison up to 1910:—

These figures, however deplorable and startling in themselves, are as nothing in comparison with what they imply. Death from drink, more than in the case of any other disease, is the ultimate and rarely attained result of the vice of habitual intoxication. Men and women may greatly injure their health, ruin their families, and be disgraceful drunkards, and yet not die of it, or make any near approach to doing so. What is the proportion of those who are morally and physically injured by drink to those who kill themselves by it, is, I suppose, unknown, but I imagine that one in a thousand is, probably, too high an estimate, and that one death among ten thousand moderate drinkers who also occasionally or frequently become intoxicated, would be nearer the mark. This would imply an increase in the consumption of alcoholic drinks, instead of which there has been an actual diminution. The fact probably is that a very large number of moderate drinkers have ceased to consume alcohol in any form, and this would account for a much larger reduction in the total than has actually occurred.

On the other hand, owing to the increase of those who are only casually employed in our great cities, and whose one luxury is the excitement of drink, a larger quantity of cheap, and injuriously adulterated spirits and other liquors is consumed, which, combined with a deficiency of wholesome food, leads more frequently to a fatal result.

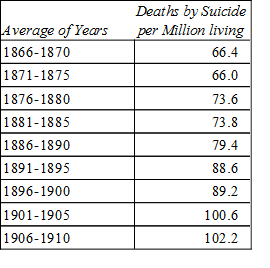

Increase of SuicideThe increase has been long known and generally admitted. It is supposed to be largely due to the ever-increasing struggle for subsistence in our great cities, the consequent increase of unemployment, and the dread of the workhouse as the only alternative to starvation. The following are the figures for the last forty-five years for which official data have been published:—

Such a table as this, occurring in a country which boasts of its enormous wealth, of its ever-increasing commercial prosperity, of its marvellous advance in science and the arts, and command of natural forces, should, surely, give us pause, and force upon us the conviction that there is something radically wrong in a social system which brings about such terrible evils.

And this should be the more certainly seen to be the case because the same increase is taking place in all those countries which approach us in their wealth and their commercial prosperity.

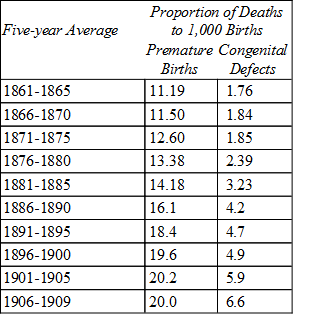

There is a group of diseases which are fatal to infants soon after birth. They have been steadily increasing during the last half-century, and call for special notice here, as they seem to indicate physical degeneration as well as personal immorality of a dangerous and perhaps even a criminal nature.

The large increase during the last forty-five years of very early infantile deaths, involving abnormalities of mother or child, seems very significant. The first may be connected with the increasing dislike of child-bearing, and unsuccessful attempts to avoid it. The second indicates some injurious condition of life of the mother, such as working at unhealthy or even deadly trades, which has certainly been largely increasing during the same period. Such work for young married women should be impossible in a civilised community.

On the vast subject of prostitution, of which the present movement for the suppression of what is called "The White Slave Traffic" is but one of the aspects, I do not propose to dwell, because I can find no statistics to show whether it has increased or decreased during the last century. But as the conditions have all been favourable for it, I have little doubt that it has increased in proportion to population. Such conditions are, the enormous growth of great cities; an increasing number of unmarried and wealthy young men; with an enormous number of girls and young women whose wages are insufficient to provide them with the rational enjoyments of life.

The proceedings of the Divorce Courts show other aspects of the result of wealth and leisure; while a friend who had been a good deal in London Society assured me that both in country houses and in London various kinds of orgies were occasionally to be met with which could hardly have been surpassed in the Rome of the most dissolute emperors.