Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Island Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

Mr. Moseley, who visited Bermuda in the Challenger, has well explained the probable origin of the vegetation. The large number of West Indian plants is no doubt due to the Gulf Stream and constant surface drift of warm water in this direction, while others have been brought by the annual cyclones which sweep over the intervening ocean. The great number of American migratory birds, including large flocks of the American golden plover, with ducks and other aquatic species, no doubt occasionally bring seeds, either in the mud attached to their feet or in their stomachs.111 As these causes are either constantly in action or recur annually, it is not surprising that almost all the species should be unchanged owing to the frequent intercrossing of freshly-arrived specimens. If a competent botanist were thoroughly to explore Bermuda, eliminate the species introduced by human agency, and investigate the source from whence the others were derived and the mode by which they had reached so remote an island, we should obtain important information as to the dispersal of plants, which might afford us a clue to the solution of many difficult problems in their geographical distribution.

Concluding Remarks.—The two groups of islands we have now been considering furnish us with some most instructive facts as to the power of many groups of organisms to pass over from 700 to 900 miles of open sea. There is no doubt whatever that all the indigenous species have thus reached these islands, and in many cases the process may be seen going on from year to year. We find that, as regards birds, migratory habits and the liability to be caught by violent storms are the conditions which determine the island-population. In both islands the land-birds are almost exclusively migrants; and in both, the non-migratory groups—wrens, tits, creepers, and nuthatches—are absent; while the number of annual visitors is greater in proportion as the migratory habits and prevalence of storms afford more efficient means for their introduction.

We find also, that these great distances do not prevent the immigration of some insects of most of the orders, and especially of a considerable number and variety of beetles; while even land-shells are fairly represented in both islands, the large proportion of peculiar species clearly indicating that, as we might expect, individuals of this group of organisms arrive only at long and irregular intervals.

Plants are represented by a considerable variety of orders and genera, most of which show some special adaptation for dispersal by wind or water, or through the medium of birds; and there is no reason to doubt that besides the species that have actually established themselves, many others must have reached the islands, but were either not suited to the climate and other physical conditions, or did not find the insects necessary to their fertilisation, and were therefore unable to maintain themselves.

If now we consider the extreme remoteness and isolation of these islands, their small area and comparatively recent origin, and that, notwithstanding all these disadvantages, they have acquired a very considerable and varied flora and fauna, we shall, I think, be convinced, that with a larger area and greater antiquity, mere separation from a continent by many hundred miles of sea would not prevent a country from acquiring a very luxuriant and varied flora, and a fauna also rich and peculiar as regards all classes except terrestrial mammals, amphibia, and some groups of reptiles. This conclusion will be of great importance in those cases where the evidence as to the exact origin of the fauna and flora of an island is less clear and satisfactory than in the case of the Azores and Bermuda.

CHAPTER XIII

THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS

Position and Physical Features—Absence of Indigenous Mammalia and Amphibia—Reptiles—Birds—Insects and Land-Shells—The Keeling Islands as Illustrating the Manner in which Oceanic Islands are Peopled—Flora of the Galapagos—Origin of the Flora of the Galapagos—Concluding Remarks.

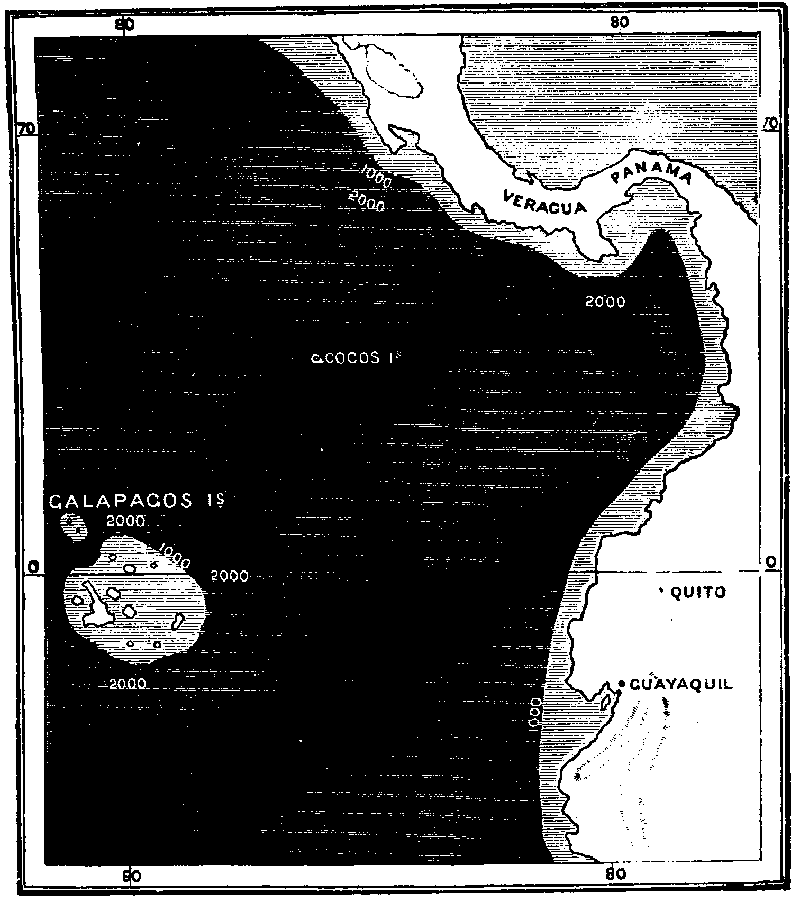

The Galapagos differ in many important respects from the islands we have examined in our last chapter, and the differences are such as to have affected the whole character of their animal inhabitants. Like the Azores, they are volcanic, but they are much more extensive, the islands being both larger and more numerous; while volcanic action has been so recent that a large portion of their surface consists of barren lava-fields. They are considerably less distant from a continent than either the Azores or Bermuda, being about 600 miles from the west coast of South America and a little more than 700 from Veragua, with the small Cocos Islands intervening; and they are situated on the equator instead of being in the north temperate zone. They stand upon a deeply submerged bank, the 1,000 fathom line encircling all the more important islands at a few miles distance, whence there appears to be a comparatively steep descent all round to the average depth of that portion of the Pacific, between 2,000 and 3,000 fathoms.

MAP OF THE GALAPAGOS AND ADJACENT COASTS OF SOUTH AMERICA.

The light tint shows where the sea is less than 1,000 fathoms deep.

The figures show the depth in fathoms.

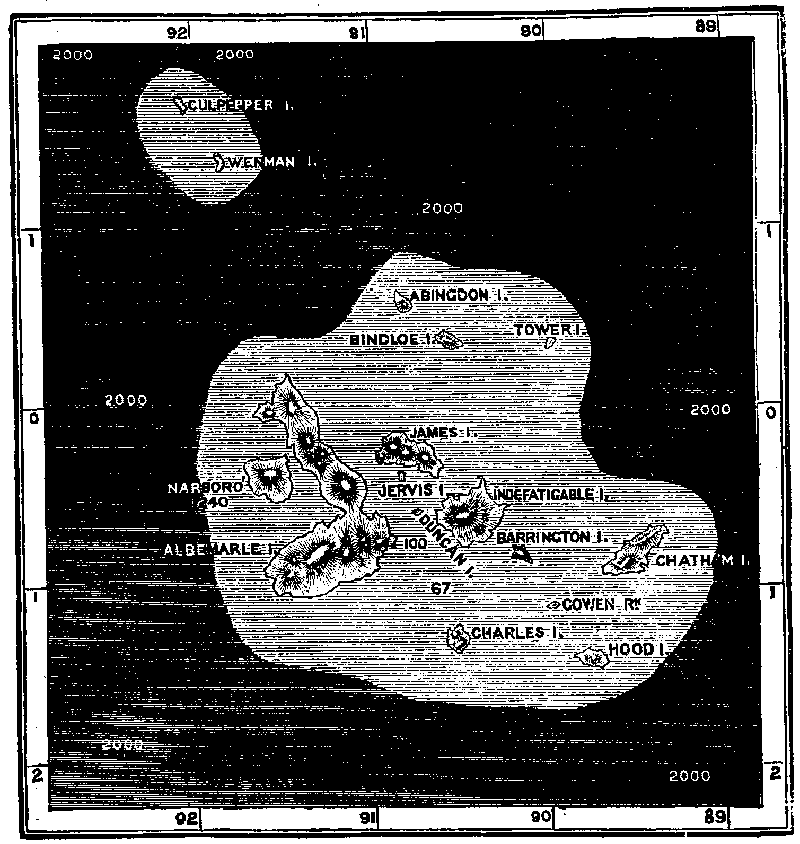

The whole group occupies a space of about 300 by 200 miles. It consists of five large and twelve small islands; the largest (Albemarle Island) being about eighty miles long and of very irregular shape, while the four next in importance—Chatham, Indefatigable, James, and Narborough Islands, are each about twenty-five or thirty miles long, and of a rounded or elongate form. The whole are entirely volcanic, and in the western islands there are numerous active volcanoes. Unlike the other groups of islands we have been considering, these are situated in a comparatively calm sea, where storms are of rare occurrence and even strong winds almost unknown. They are traversed by ocean currents which are strong and constant, flowing towards the north-west from the coast of Peru; and these physical conditions have had a powerful influence on the animal and vegetable forms by which the islands are now inhabited. The Galapagos have also, during three centuries, been frequently visited by Europeans, and were long a favourite resort of buccaneers and traders, who found an ample supply of food in the large tortoises which abound there; and to these visits we may perhaps trace the introduction of some animals whose presence it is otherwise difficult to account for. The vegetation is generally scanty, but still amply sufficient for the support of a considerable amount of animal life, as shown by the cattle, horses, asses, goats, pigs, dogs, and cats, which now run wild in some of the islands.

MAP OF THE GALAPAGOS.

The light tint shows a depth of less than 1,000 fathoms.

The figures show the depth in fathoms.

Absence of Indigenous Mammalia and Amphibia.—As in all other oceanic islands, we find here no truly indigenous mammalia, for though there is a mouse of the American genus Hesperomys, which differs somewhat from any known species, we can hardly consider this to be indigenous; first, because these creatures have been little studied in South America, and there may yet be many undescribed species, and in the second place because even had it been introduced by some European or native vessel, there is ample time in two or three hundred years for the very different conditions to have established a marked diversity in the characters of the species. This is the more probable because there is also a true rat of the Old World genus Mus, which is said to differ slightly from any known species; and as this genus is not a native of the American continents we are sure that it must have been recently introduced into the Galapagos. There can be little doubt therefore that the islands are completely destitute of truly indigenous mammalia; and frogs and toads, the only tropical representatives of the Amphibia, are equally unknown.

Reptiles.—Reptiles, however, which at first sight appear as unsuited as mammals to pass over a wide expanse of ocean, abound in the Galapagos, though the species are not very numerous. They consist of land-tortoises, lizards and snakes. The tortoises consist of two peculiar species, Testudo microphyes, found in most of the islands, and T. abingdonii recently discovered on Abingdon Island, as well as one extinct species, T. ephippium, found on Indefatigable Island. These are all of very large size, like the gigantic tortoises of the Mascarene Islands, from which, however, they differ in structural characters; and Dr. Günther believes that they have been originally derived from the American continent.112 Considering the well known tenacity of life of these animals, and the large number of allied forms which have aquatic or sub-aquatic habits, it is not a very extravagant supposition that some ancestral form, carried out to sea by a flood, was once or twice safely drifted as far as the Galapagos, and thus originated the races which now inhabit them.

The lizards are five in number; a peculiar species of gecko, Phyllodactylus galapagensis, and four species of the American family Iguanidæ. Two of these are distinct species of the genus Tropidurus, the other two being large, and so very distinct as to be classed in peculiar genera. One of these is aquatic and found in all the islands, swimming in the sea at some distance from the shore and feeding on seaweed; the other is terrestrial, and is confined to the four central islands. These last were originally described as Amblyrhynchus cristatus by Mr. Bell, and A. subcristatus by Gray; they were afterwards placed in two other genera Trachycephalus and Oreocephalus (see Brit. Mus. Catalogue of Lizards), while in a recent paper by Dr. Steindachner, the marine species is again classed as Amblyrhynchus, while the terrestrial form is placed in another genus Conolophus, both genera being peculiar to the Galapagos.

How these lizards reached the islands we cannot tell. The fact that they all belong to American genera or families indicates their derivation from that continent, while their being all distinct species is a proof that their arrival took place at a remote epoch, under conditions perhaps somewhat different from any which now prevail. It is certain that animals of this order have some means of crossing the sea not possessed by any other land vertebrates, since they are found in a considerable number of islands which possess no mammals nor any other land reptiles; but what those means are has not yet been positively ascertained.

It is unusual for oceanic islands to possess snakes, and it is therefore somewhat of an anomaly that two species are found in the Galapagos. Both are closely allied to South American forms, and one is hardly different from a Chilian snake, so that they indicate a more recent origin than in the case of the lizards. Snakes it is known can survive a long time at sea, since a living boa-constrictor once reached the island of St. Vincent from the coast of South America, a distance of two hundred miles by the shortest route. Snakes often frequent trees, and might thus be conveyed long distances if carried out to sea on a tree uprooted by a flood such as often occurs in tropical climates and especially during earthquakes. To some such accident we may perhaps attribute the presence of these creatures in the Galapagos, and that it is a very rare one is indicated by the fact that only two species have as yet succeeded in obtaining a footing there.

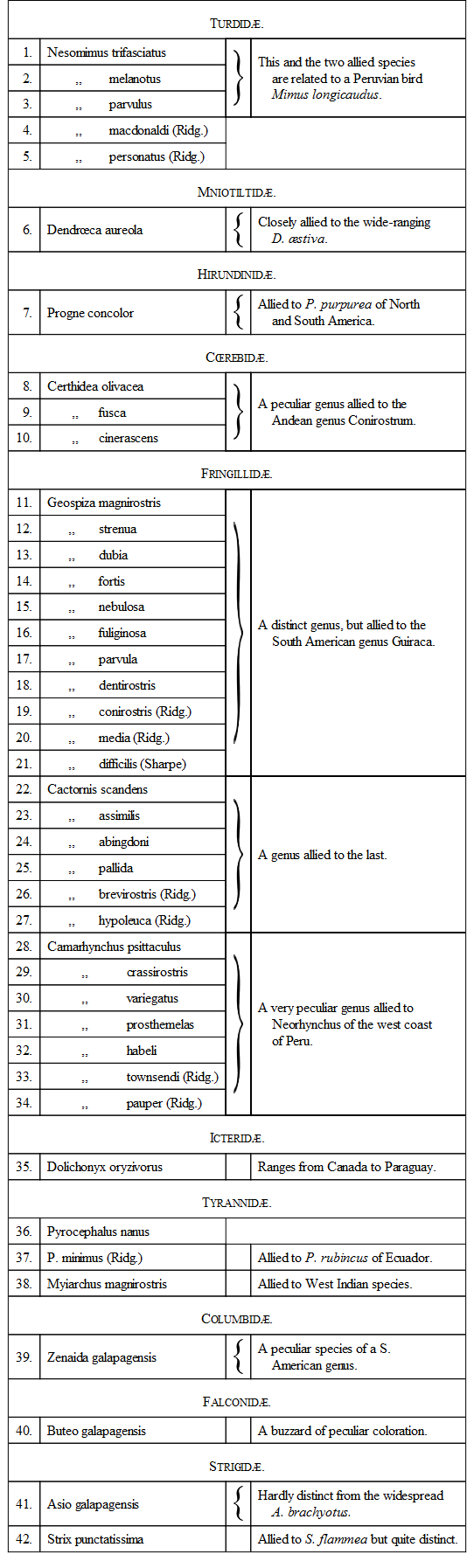

Birds.—We now come to the birds, whose presence here may not seem so remarkable, but which yet present features of interest not exceeded by any other group. About seventy species of birds have now been obtained on these islands, and of these forty-one are peculiar to them. But all the species found elsewhere, except one, belong to the aquatic tribes or the waders which are pre-eminently wanderers, yet even of these eight are peculiar. The true land-birds are forty-two in number, and all but one are entirely confined to the Galapagos; while three-fourths of them present such peculiarities that they are classed in distinct genera. All are allied to birds inhabiting tropical America, some very closely; while one—the common American rice-bird which ranges over the whole northern and part of the southern continents—is the only land-bird identical with those of the mainland. The following is a list of these land-birds taken from Mr. Salvin's memoir in the Transactions of the Zoological Society for the year 1876, to which are added nine species collected in 1888 and described by Mr. Ridgway in the Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum (XII. p. 101) and some additional species obtained in 1889.

We have here every gradation of difference from perfect identity with the continental species to genera so distinct that it is difficult to determine with what forms they are most nearly allied; and it is interesting to note that this diversity bears a distinct relation to the probabilities of, and facilities for, migration to the islands. The excessively abundant rice-bird, which breeds in Canada and swarms over the whole United States, migrating to the West Indies and South America, visiting the distant Bermudas almost every year, and extending its range as far as Paraguay, is the only species of land-bird which remains completely unchanged in the Galapagos; and we may therefore conclude that some stragglers of the migrating host reach the islands sufficiently often to keep up the purity of the breed. Next, we have the almost cosmopolite short-eared owl (Asio brachyotus), which ranges from China to Ireland, and from Greenland to the Straits of Magellan, and of this the Galapagos bird is probably only one of the numerous varieties. The little wood warbler (Dendrœca aureola) is closely allied to a species which ranges over the whole of North America and as far south as New Grenada. It has also been occasionally met with in Bermuda, an indication that it has considerable powers of flight and endurance. The more distinct species—as the tyrant fly-catchers (Pyrocephalus and Myiarchus), the ground-dove (Zenaida), and the buzzard (Buteo), are all allied to non-migratory species peculiar to tropical America, and of a more restricted range; while the distinct genera are allied to South American groups of thrushes, finches, and sugar-birds which have usually restricted ranges, and whose habits are such as not to render them likely to be carried out to sea. The remote ancestral forms of these birds which, owing to some exceptional causes, reached the Galapagos, have thus remained uninfluenced by later migrations, and have, in consequence, been developed into a variety of distinct types adapted to the peculiar conditions of existence under which they have been placed. Sometimes the different species thus formed are confined to one or two of the islands only, as the three species of Certhidea, which are divided between the islands but do not appear ever to occur together. Nesomimus parvulus is confined to Albemarle Island, and N. trifasciatus to Charles Island; Cactornis pallida to Indefatigable Island, C. brevirostris to Chatham Island, and C. abingdoni to Abingdon Island.

Now all these phenomena are strictly consistent with the theory of the peopling of the islands by accidental migrations, if we only allow them to have existed for a sufficiently long period; and the fact that volcanic action has ceased on many of the islands, as well as their great extent, would certainly indicate a considerable antiquity.

The great difference presented by the birds of these islands as compared with those of the equally remote Azores and Bermudas, is sufficiently explained by the difference of climatal conditions. At the Galapagos there are none of those periodic storms, gales, and hurricanes which prevail in the North Atlantic, and which every year carry some straggling birds of Europe or North America to the former islands; while, at the same time, the majority of the tropical American birds are nonmigratory, and thus afford none of the opportunities presented by the countless hosts of migrants which pass annually northward and southward along the European, and especially along the North American coasts. It is strictly in accordance with these different conditions that we find in one case an almost perfect identity with, and in the other an almost equally complete diversity from, the continental species of birds.

Insects and Land-shells.—The other groups of land-animals add little of importance to the facts already referred to. The insects are very scanty; the most plentiful group, the beetles, only furnishing about forty species belonging to thirty-two genera and nineteen families. The species are almost all peculiar, as are some of the genera. They are mostly small and obscure insects, allied either to American or to world-wide groups. The Carabidæ and the Heteromera are the most abundant groups, the former furnishing six and the latter nine species.113

The land-shells are not abundant—about twenty in all, most of them peculiar species, but not otherwise remarkable. The observation of Captain Collnet, quoted by Mr. Darwin in his Journal, that drift-wood, bamboos, canes, and the nuts of a palm, are often washed on the south-eastern shores of the islands, furnishes an excellent clue to the manner in which many of the insects and land-shells may have reached the Galapagos. Whirlwinds also have been known to carry quantities of leaves and other vegetable débris to great heights in the air, and these might be then carried away by strong upper currents and dropped at great distances, and with them small insects and mollusca, or their eggs. We must also remember that volcanic islands are subject to subsidence as well as elevation; and it is quite possible that during the long period the Galapagos have existed some islands may have intervened between them and the coast, and have served as stepping-stones by which the passage to them of various organisms would be greatly facilitated. Sunken banks, the relics of such islands, are known to exist in many parts of the ocean, and countless others, no doubt, remain undiscovered.

The Keeling Islands as Illustrating the Manner in which Oceanic Islands are Peopled.—That such causes as have been here adduced are those by which oceanic islands have been peopled, is further shown by the condition of equally remote islands which we know are of comparatively recent origin. Such are the Keeling or Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean, situated about the same distance from Sumatra as the Galapagos from South America, but mere coral reefs, supporting abundance of cocoa-nut palms as their chief vegetation. These islands were visited by Mr. Darwin, and their natural history carefully examined. The only mammals are rats, brought by a wrecked vessel and said by Mr. Waterhouse to be common English rats, "but smaller and more brightly coloured;" so that we have here an illustration of how soon a difference of race is established under a constant and uniform difference of conditions. There are no true land-birds, but there are snipes and rails, both apparently common Malayan species. Reptiles are represented by one small lizard, but no account of this is given in the Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle, and we may therefore conclude that it was an introduced species. Of insects, careful collecting only produced thirteen species belonging to eight distinct orders. The only beetle was a small Elater, the Orthoptera were a Gryllus and a Blatta; and there were two flies, two ants, and two small moths, one a Diopæa which swarms everywhere in the eastern tropics in grassy places. All these insects were no doubt brought either by winds, by floating timber (which reaches the islands abundantly), or by clinging to the feathers of aquatic or wading birds; and we only require more time to introduce a greater variety of species, and a better soil and more varied vegetation, to enable them to live and multiply, in order to give these islands a fauna and flora equal to that of the Bermudas. Of wild plants there were only twenty species, belonging to nineteen genera and to no less than sixteen natural families, while all were common tropical shore plants.114 These islands are thus evidently stocked by waifs and strays brought by the winds and waves; but their scanty vegetation is mainly due to unfavourable conditions—the barren coral rock and sand, of which they are wholly composed, together with exposure to sea-air, being suitable to a very limited number of species which soon monopolise the surface. With more variety of soil and aspect a greater variety of plants would establish themselves, and these would favour the preservation and increase of more insects, birds, and other animals, as we find to be the case in many small and remote islands.115

Flora of the Galapagos.—The plants of these islands are so much more numerous than the known animals, even including the insects, they have been so carefully studied by eminent botanists, and their relations throw so much light on the past history of the group, that no apology is needed for giving a brief outline of the peculiarities and affinities of the flora. The statements we shall make on this subject will be taken from the Memoir of Sir Joseph Hooker in the Linnæan Transactions for 1851, founded on Mr. Darwin's collections, and a later paper by N. J. Andersson in the Linnæa of 1861, embodying more recent discoveries.

The total number of flowering plants known at the latter date was 332, of which 174 were peculiar to the islands, while 158 were common to other countries.116 Of these latter about twenty have been introduced by man, while the remainder are all natives of some part of America, though about a third part are species of wide range extending into both hemispheres. Of those confined to America, forty-two are found in both the northern and southern continents, twenty-one are confined to South America, while twenty are found only in North America, the West Indies, or Mexico. This equality of North American and South American species in the Galapagos is a fact of great significance in connection with the observation of Sir Joseph Hooker that the peculiar species are allied to the plants of temperate America or to those of the high Andes, while the non-peculiar species are mostly such as inhabit the hotter regions of the tropics near the level of the sea. He also observes that the seeds of this latter class of Galapagos plants often have special means of transport, or belong to groups whose seeds are known to stand long voyages and to possess great vitality. Mr. Bentham also, in his elaborate account of the Compositæ,117 remarks on the decided Central American or Mexican affinities of the Galapagos species, so that we may consider this to be a thoroughly well-established fact.

The most prevalent families of plants in the Galapagos are the Compositæ (40 sp.), Gramineæ (32 sp.), Leguminosæ (30 sp.), and Euphorbiaceæ (29 sp.). Of the Compositæ most of the species, except such as are common weeds or shore plants, are peculiar, but there are only two peculiar genera, allied to Mexican forms and not very distinct; while the genus Lipochæta, represented here by a single species, is only found elsewhere in the Sandwich Islands though it has American affinities.

Origin of the Galapagos Flora.—These facts are explained by the past history of the American continent, its separation at various epochs by arms of the sea uniting the two oceans across what is now Central America (the last separation being of recent date, as shown by the considerable number of identical species of fishes on both sides of the isthmus), and the influence of the glacial epoch in driving the temperate American flora southward along the mountain plateaus.118 At the time when the two oceans were united a portion of the Gulf Stream may have been diverted into the Pacific, giving rise to a current, some part of which would almost certainly have reached the Galapagos, and this may have helped to bring about that singular assemblage of West Indian and Mexican plants now found there. And as we now believe that the duration of the last glacial epoch in its successive phases was much longer than the time which has elapsed since it finally passed away, while throughout the Miocene epoch the snow-line would often be lowered during periods of high excentricity, we are enabled to comprehend the nature of the causes which may have led to the islands being stocked with those north tropical or mountain types which are so characteristic a feature of that portion of the Galapagos flora which consists of peculiar species.