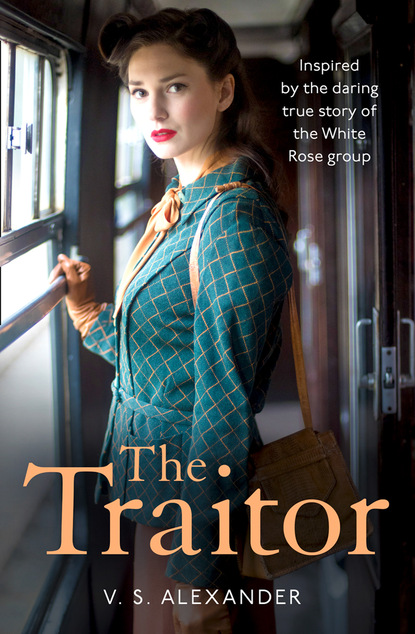

The Traitor

In those lands yet untouched by war’s deadly grip, the tall birches shimmered in East Prussia, the wide steppes of Russia opened to gently swelling hills; and, at those times, with the train windows open, the wheels clacking in rhythmic motion along the tracks, the July heat dissipating with the setting sun—in those times—one could almost forget the cares of war and pretend that all was right with the world.

But there were other distractions on the long trip to the Front. I traveled with a young woman named Greta, also a volunteer nurse, whom I knew little about other than she had her own plans, as I did, to eventually return to Munich.

Because my father worked in a field related to medicine, I was drawn to it and, furthermore, I had no better idea what to do with my life. I had come to volunteer nursing after my experiences in the League of German Girls. Administering medical care to the ill gave me satisfaction. Changing bandages, helping children who suffered from cuts and scrapes, and learning about the body became my “profession” in the years following 1939. Although nursing allowed me to get away from my strict father and not immediately give in to the pressure to marry and produce children, as the Reich demanded, one strong disadvantage remained. The German Red Cross became a potent arm of the Nazi regime. We were expected to embrace the Reich’s teachings on Aryan supremacy and blindly follow Hitler—both of which I innocently ignored in thinking and action. My father’s strictness had inadvertently instilled an anxious tension inside me, which fed my natural shyness. But something stronger bubbled in me as well: an urge to be free, to be my own woman, a nascent rebelliousness.

One night Greta offered me a smoke as I read a biology text in our cramped quarters. The book offered little excitement, but any gathered kernels of knowledge I hoped would help me secure a medical career as a woman under National Socialism.

Not being a smoker, I declined her offer. Cigarettes weren’t cheap and were often sold on the black market. I wondered where she had gotten them. “Good” women weren’t supposed to smoke, but one of the reasons many became volunteer nurses was for the occasional freedom it offered from such restrictions. Mostly, cigarettes went to soldiers. She also held up a bottle of clear liquid. The red label, printed in Polish, read Wódka, and when Greta pulled out the stopper, the odor of the sharp, medicinal spirit floated past me.

She looked older than her years. The emerging frown lines on her face and the chewed cuticles on her fingers led me to believe that her life had not been happy. Perhaps they were signs of anxiety about the war, or life in general, but she couldn’t have been much more than my age of twenty. Still, she made herself pretty in a way that was aimed at the men traveling with us.

Greta sat in the chair opposite mine, sitting backward to the forward motion of the train as we sped over the vast plain. She lit her cigarette and a plume of smoke rushed to my face but dispersed quickly out the open window. I closed my book.

“Have you spoken to any of them?” She hitched her right thumb over her shoulder and rested her left elbow on the lip of the window, keeping the lit end of the cigarette near the opening. The spark flared red in the rushing wind.

“A few,” I replied. “I try not to get too familiar.” I had no desire to foster romantic relationships with army or medical corpsmen. I was headed to the Front to do a job, not get a husband; and, after all, being somewhat fatalistic, I wondered how long a potential mate would be alive in these dire times. The war on the Eastern Front was dragging on despite the Reich’s claims of victory after victory. To be held by a man, to taste his lips upon mine, would be nice had such a prospect occurred, but a relationship seemed a matter of secondary importance considering how men were dying for the Reich.

Greta took a drag on her cigarette, took a gulp of vodka, and then held the bottle out to me.

I pulled down the shade on our compartment door. “Where did you get this contraband?”

“A lady never tells.” Greta smiled wryly and tapped her nails on the bottle. “Some of them are very good-looking, including the Russian. Whatever happened to all those lectures about racial purity we had to sit through? Natalya Petrovich? Alexander Schmorell?”

Her question irked me—I was a native Russian living in Germany—my parents never let me forget that fact. We knew the Reich rumblings about the Untermensch, the subhumans, but non-Jewish Russians living in Germany had mostly been able to live as citizens, particularly those already assimilated. One had little choice in the Reich but to obey; still, I was proud to be traveling to my homeland on what I considered a mission of mercy. I took the bottle and tipped it back, the strong drink burning my throat, the fire settling in a warm ball in my stomach.

“We’re all German now. Have a look at my papers. The Reich needs men … and nurses.” After what had happened to my Jewish friends since the Nazis came to power, I wanted nothing to do with creating a new racial order in the East—a thought repugnant to me. All I was concerned about was saving lives, and if that compassion extended to my fellow Russians, so be it. Of course, I didn’t really know what the future held.

She shrugged off my rebuff and continued her daydreams about men. “It’s hard to choose from among them,” she said, her eyes on my mouth as it puckered from another swig of liquor.

“Not the best vodka I’ve ever had,” I said, although my experience with drink was limited.

“One of them is Russian, he told me so. Alexander. Nice-looking …” Greta puffed on her cigarette, which had prematurely burned to her fingertips in the train’s rushing wake, and then tossed it out the window. “But the one he’s traveling with—a real doll.” She fanned her fingers in front of her face.

I took another gulp of the vodka and a dull stupor overtook me. I yawned and stretched out in my seat, which served as an uncomfortable bed. “The sun has set. We need to pull down the blackout shades.”

“Another dull night with only dreams to keep me company,” Greta said, and settled back in her seat. “Things will pick up when we get to the Front.”

I wondered if she was right, for I feared the Front would bring only tragedy and misery. My excitement about returning to Russia was tempered by the prospect of what might lay ahead. Secretly, I wondered if I was prepared to deal with what I might witness. I deflected the phantom images of dead and wounded soldiers, the bombed-out buildings that filled my mind—mental pictures reinforced by the destruction I had seen in Warsaw. They didn’t fade easily.

After what seemed like an endless trip through Russia, we arrived in early August at Vyazma and the home of the 252nd Division, to which the men were assigned. Greta and I stepped out of our car to stretch our legs. Our eventual stop would be to the northwest in the town of Gzhatsk, about 180 kilometers west of Moscow.

I had barely stepped onto the ground to the sound of blaring military music when Greta cocked her head toward the men she had spoken about. “There they are.” She discreetly pointed at them as they exited their car, located farther up the train from ours. “They hang together like thieves.”

Greta identified them: Hans, tall with dark hair and the handsome profile of a movie actor, a pleasing face of wonderful proportion, a thin nose over sensuous lips, a slight cleft to the chin, and inquisitive eyes under dark brows; Willi, with slick-backed blond hair, which sometimes hung in wind-pushed wisps across his forehead. He was handsome as well, with an oval face and broad chin, a man who looked the most prone to silence and grave thoughts of the three. The last was the “Russian” as Greta called him, a man she had heard the others call “Alex.” He was tall and lanky, with a full head of hair sweeping back from his face. He seemed to be the one who smiled the most, with fun in his soul, who perhaps didn’t take life as seriously as the others.

I gave them a cursory glance, more interested in putting names to faces than in cultivating romantic notions.

I was unprepared for what I saw after my gaze shifted from the men. Vyazma was little more than the shattered remains of buildings surrounded by craters blasted into the earth. One wooden church, the only intact structure in the village, stood perched on a small hill. Nothing moved among the rubble except the German troops. I wondered where all the life had gone. Had its people been killed, all animal life destroyed by the advance?

The loudspeakers installed by the Wehrmacht blared into my ears. I walked away from the train, leaving Greta and the others behind, and stood next to a burned-out home, nothing more than blackened timbers and the shell of a window. The smell of death, like rotted meat, filled my nose. I spun away, unable to stand the stench, and discovered the source. Beyond the house lay the corpse of a decaying dog. Swarms of black flies buzzed around its body. The animal reminded me of a dog left to fend on its own after a Jewish family in Munich had disappeared. It was taken care of for a time by neighbors, but then it too vanished, like the village before me. Nothing but desiccated earth remained in a town that had once brimmed with life.

After boarding the train, on our way to Gzhatsk, my mood deepened as the shadows lengthened over the plains. I found it hard to believe that the war in Russia had been going on for more than a year with hundreds of thousands of men, maybe a million or more, traveling this route in the military surge to take Moscow, Leningrad to the north, and the Russian cities to the south. Greta must have recognized my reluctance to talk, because even though we were compartment mates, she left me to my thoughts and socialized with the two other nurses on board.

Something—at first inexplicable—was happening. When I gazed from the train at the vast landscape, the summer wind lashing the birches, the rain and the sun painting the trees in resplendent splashes of silver, I felt at one with the earth, at one with my native country, profound memories resurrecting from my distant childhood. A kind of “Russian fever” had overtaken me as if I had become part of the land of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Pushkin, leaving Goethe and Schiller behind. Something stirred in my soul, opening me to unfamiliar feelings that disturbed me but at the same time thrilled me. An ecstatic emptiness, a heaven filled with stars yet undefined by space, melancholy tempered by shining hope, overcame me. Deeply buried yearnings stirred within me as I recalled what it was like to be a child in Leningrad, unaware of my parents’ worries about Stalin, and, later, Hitler.

Instead of life on the busy streets of Munich, I understood what it was to be free of constraints. Ribbons of rivers, lush meadows, and verdant woods spread out before me. I saw for the first time what Hitler desired in his perverted megalomania, his Lebensraum, the territory he desired for Germany and the ever-expanding Reich. The “subhumans” would be the tenders of the fields, the Aryan race the masters. But Hitler and his henchmen had not taken into account the fullness and determination of the Russian spirit, and a splinter of that essence pricked my skin. That fact was never clearer to me than when we reached Gzhatsk.

The city, like Vyazma, lay in ruins. Churches, shops, and homes had been obliterated in the drive to subjugate Moscow. The Front was a mere ten kilometers away, and shells burst within earshot. A few even landed near Gzhatsk, shaking the earth with their explosions. What people remained here, outside of troops, wandered about the destroyed city with soil smeared on their ragged clothes and shock in their eyes. Little emotion showed as they passed us—well-fed Germans on our way to a medical camp in the woods safely away from the danger of bullets and bombs. A strong and prevailing sadness filled my heart upon seeing these people.

For several days, we set up additional tents, made sure our uniforms, aprons, and supplies were unpacked, listened to medical lectures from stuffy Wehrmacht doctors, played cards, and offered aid to the small number of wounded in camp. Some of the medical corpsmen, including Willi and Alex, passed around vodka in the evening. I could tell by the sighing and excessive cigarette smoking that everyone was itching to do something besides sit in camp. At night, the shells would crash near the city and light up the woods with their explosive flares.

The first truckload of new casualties arrived about a week later. Everyone jumped into their roles, the medical corpsmen and the nurses attending the doctors. One physician ordered me to help Alex, who leaned over a man with a nearly severed leg. The soldier’s head lolled on the gurney and he mouthed words I couldn’t hear above the shouted orders, the clanging of metal medical tables and instruments, and moans of the wounded. Alex pulled on his gloves and apron and I did the same.

“What’s he saying?” I asked.

“Something about killing Hitler,” Alex said. “He says if he loses his leg, he’ll shoot the Führer.” He bent down and studied the tourniquet and the large gash in the man’s limb. The bandages, soaked with blood, had turned from crimson to brownish red. “I have bad news for him. When he comes to, he’ll find his left leg missing. The shrapnel cut most of the way through. All we can do is make him comfortable until the doctor lops it off.”

I sensed that Alex was horrified by the man’s injuries, but that, as a medical corpsman, he fought against the nightmarish atmosphere of the tent. The joie de vivre that ran through him lifted his spirits.

“Natalya, isn’t it?”

I nodded.

His eyes brightened despite the misery around us. “Get fresh bandages and we’ll clean the injury and apply antiseptic.” He studied his surroundings as the medical staff dashed about the large tent. “It’s going to be a while before the doctor can operate.” Hans and Greta hovered over a nearby bench where a man lay bleeding from a gaping shoulder wound.

I gathered the bandages and returned to the gurney. The now delirious soldier had clutched Alex’s shoulders and pulled him so close he was screaming in his ear. My comrade shushed the man and pushed him down on his makeshift bed. Alex attempted to calm him as an orderly administered a shot of morphine. Alex and I worked as a team until the wound had been cleaned and dressed. Under the influence of the drug, the soldier slipped into sleep.

When the wounded in our care had been attended to, Alex and I stripped off our gear and stepped outside, clear of the tent and away from the commotion. He ran his fingers through his cliff of hair, lit his black pipe, and puffed on it. The smoke dispersed in hazy shafts in the few rays of sun that penetrated the thick canopy.

“You do good work,” Alex said between puffs and stretches of his long legs. “You hope to remain a nurse?”

“Probably,” I said, and sat on the damp earth beneath a pine tree. The cool air bathed me with its woody fragrance, a refreshing change from the stifling conditions and antiseptic smell of the stuffy tent. “That’s why I’m here—to find out. I’ve passed my Abitur and I may decide to go on in biology or philosophy at the university.” I picked up some decaying brown needles and threw them absentmindedly in the direction of the tent. “That soldier was out of his mind with pain, but then we’ve all been under strain the past few years—dealing with rations … conditions we have no control over …”

Alex sat beside me. The smoke from his pipe encircled us with a pleasant, earthy scent that reminded me of a fall campfire—and it kept the mosquitoes away. “Yes, he was saying things he shouldn’t have … words he could be executed for if anyone was to report him.” He chomped down on the pipe stem. “That is, if someone felt it necessary to betray him.”

“… necessary to betray …” His words astonished me. “War changes everything, despite our rules and regulations,” I replied after his comment had sunk in. “Drinking and smoking are forbidden, yet nearly everyone does it. Greta wears makeup when she can. Why should we worry about things like getting tipsy or having a cigarette when our next breath could be extinguished by a bullet?” I looked toward the medical tent, partially obscured by pine branches. “No court would convict a man who was crazed with pain.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure … We are dealing with the Reich.” He leaned back in the circular shade of the tree and thought for a moment. “How would you like to do something that’s strictly forbidden?”

A thrill raced through me at his unexpected question. “I guess I’d have to know how forbidden this something is?”

“You can keep a secret—after all, you’re Russian like me.”

“Yes,” I said, and added to protect myself, “but we’re Germans too.”

He paused and then said, “Fraternization with the enemy.” He spoke matter-of-factly, as if the words meant nothing more than “let’s have breakfast.”

I assumed he didn’t mean clandestine meetings with Russian soldiers or partisans, but I wasn’t really sure of his objective. No matter his exact intent, such activity was risky. I must have displayed some hesitation, because he settled against the tree as if nothing had been said.

“I’ve met a woman who has welcomed me into her home—Sina,” he said. “Willi and Hans have met other Russians, but I’d like to take you to Sina’s if you’re game. We drink and sing songs, sometimes dance. It’s something to look forward to in this terrible time.”

“You’d never met her before coming here?”

Alex laughed. “Never. Hans, Willi, and I like meeting the people. We feel we can learn something from our enemies.” His voice lifted on the last word in a sarcastic jibe and then lowered. “All Russians are family to me.”

Half of me wanted to go, but the other half was worried about being found out. If we were caught, the least punishment for me might mean expulsion from my work and a trip back to Munich shrouded in disgrace, at worst conviction of a crime and imprisonment. I’d often thought of prison, and my neighbors and friends who had disappeared. Even talking about them was like committing a crime.

Alex’s eyes retained their sparkle despite the deep shadows. I found it hard to resist his charm, bordering on good-natured innocence, so I nodded despite my natural inclination to stay at the camp. “It would be an adventure, Alex. I’d like to meet a fellow Russian.”

He smiled broadly and tapped the embers of his pipe on a patch of soggy ground. “Tonight, then. Please call me ‘Shurik’—all my best friends do.”

That evening, as we walked to a farmhouse on the outskirts of the city, Alex told me about his Russian family. His mother had died when he was small, and his father, a doctor, decided to move the family to Munich when Alex was four years old. A nanny became his surrogate mother and spoke to him in Russian, as my parents had after we left Leningrad. Therefore, we were both fluent in Russian and German.

Alex was even more rhapsodic about Russia than I, although both of us were affected by our rediscovered love of the country. Weaving in and out of the woods, we talked about customs and holidays and pranks we remembered from our childhoods, filling us with laughter. We traveled several kilometers down a dirt road far away from the military camp. The evening breeze whispered underneath the pines like a soft brush stroked against velvet. But on the eastern horizon, gunfire traced in yellow streaks and volleys of shells exploded in vibrant bursts against the deepening twilight.

The farmhouse, on the southern edge of a forested patch of land, resembled a string of huts jumbled together. There was no electricity here; an oil lamp burned brightly in the window. A cow lowed from one of the huts to the south of the main house, and near there stood a chicken roost smothered in downy feathers.

A grasshopper flew on waxy wings from a weedy patch in the middle of the road and I jumped from the sudden scare. I landed against Alex and he laughed at my girlish behavior. A large white moth circled us and then flitted away toward the yellow lamplight.

Alex grabbed my hand and pulled me to a stop. “There’s something I want you to know before we go inside,” he said. “Sina loves me and I believe she will love you, but I’ve told her certain things that only a few people know.”

“Your chums, Hans and Willi, I suppose,” I said without thinking.

He turned toward the east, facing the indigo light layering the horizon. I followed his gaze and was still able to make out his eyes, which had transformed from their usual joyful look to one of solemnity. “Hans knows more about me than almost anyone.” He dug his bootheel into the soft earth. “I never wanted to be here. In fact, I didn’t want to swear allegiance to Hitler and the Wehrmacht. I asked to be discharged from service, but my request was denied.” He turned and looked at me with large, questioning eyes. “You may understand …” He pointed to the hut. “As Sina does …”

I did understand, but the only courageous affirmation I could muster was a nod.

“Let’s go inside,” he said. “Sina will be waiting.”

Alex stepped to the door, knocked, and called the woman’s name. Sina, probably not much older than we, welcomed “Shurik” and me with a kiss on both cheeks and invited us in. Even though the war raged only a few kilometers from her home, she seemed to be in good spirits and looked nothing like the peasant woman I had pictured in my mind. She was thin, with long black hair braided artfully around her head. She wore no babushka or long apron covering a simple dress. Instead, she was attired in a feminine version of a navy man’s suit, a blue pinstripe blouse with an overlapping collar held together by white buttons and a matching skirt, which flowed to her bare ankles.

The hut was comfortable and warm. An additional kind of warmth came from the glow of life inside. The meager furnishings consisted of a small table, a chair, and a pine bed large enough to fit the woman and her two small children, Dimitri and Anna. They sat on their knees at one side of the table and spooned soup from wooden bowls. A samovar and several books sat on the opposite end; a guitar and balalaika lay with their fingerboards crossed at the foot of the bed; red and gold weavings of poppies, and bold geometric designs in red and blue stitching adorned what would otherwise have been bare wooden walls. A painted icon of a weeping Christ hung above the bed in a sparkling silver frame.

“Sit, sit,” Sina insisted. “I don’t have enough chairs. Shurik, you sit on the floor on the old rug.”

Alex obliged, crossing his long legs and exposing the black military boots under his gray uniform pants.

“I have no tea,” Sina said, “so let us drink vodka.” She dipped like a graceful swan and withdrew a brown bottle from under the bed. Taking three samovar cups, she poured the vodka, and handed us our two.

“Za Zdarovje,” Alex said, raising the cup to our health, followed by toasts to our meeting and friendship.

Sina sat on the bed with her legs folded underneath her thin body. Dimitri and Anna put their bowls in a washbasin and took their places on either side of their mother. “So, you are new to Russia,” she said to me.

I put the samovar cup on the table, having drained its contents. “I was born in Russia, like Shurik, but I haven’t been back since my parents left Leningrad when I was seven. I’m a volunteer nurse.”

Sina lifted her hands in a wild flourish. “You’ve missed nothing. Stalin and Bolshevism have ruined our country and killed more of our people than we can count—”

I interrupted her. “That’s why we left—because of the Five-Year Plan. My father had friends who disappeared in the night never to be seen again.”

“Then came the purges of the Terror,” Sina continued. “It’s lucky we have an army at all. Many military officers were liquidated because the General Secretary thought they might be a threat to his power.” Her eyes blazed from across the room. “And we believed the Germans had come to liberate us from Stalin … We were wrong.” She lowered her head and shook it slowly. “Instead, they’re killing us where we stand, and we are burning our homes and crops so the Wehrmacht will get no use from them.” Her hand crept toward the pillows to her right. “We’ve been instructed to kill Germans.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.