Полная версия

Полная версияThe Lancashire Witches: A Romance of Pendle Forest

It being agreed among the party to rest for an hour at the little hostel, and partake of some refreshment, Nicholas went to look after the horses, while Roger Nowell and Richard remained in the room with the pedlar. Bess Whitaker owned an extensive farm-yard, provided with cow-houses, stables, and a large barn; and it was to the latter place that the two grooms proposed to repair with Sparshot and play a game at loggats on the clay floor. No one knew what had become of the reeve; for, on depositing the poor pedlar at the door of the hostel, he had mounted his horse and ridden away. Having ordered some fried eggs and bacon, Nicholas wended his way to the stable, while Bess, assisted by a stout kitchen wench, busied herself in preparing the eatables, and it was at this juncture that Master Potts entered the house.

Bess eyed him narrowly, and was by no means prepossessed by his looks, while the muddy condition of his habiliments did not tend to exalt him in her opinion.

"Yo mey yersel a' whoam, mon, ey mun say," she observed, as the attorney seated himself on the bench beside her.

"To be sure," rejoined Potts; "where should a man make himself at home, if not at an inn? Those eggs and bacon look very tempting. I'll try some presently; and, as soon as you've done with the frying-pan, I'll have a pottle of sack."

"Neaw, yo winna," replied Bess. "Yo'n get nother eggs nor bacon nor sack here, ey can promise ye. Ele an whoat-kekes mun sarve your turn. Go to t' barn wi' t' other grooms, and play at kittle-pins or nine-holes wi' hin, an ey'n send ye some ele."

"I'm quite comfortable where I am, thank you, hostess," replied Potts, "and have no desire to play at kittle-pins or nine-holes. But what does this bottle contain?"

"Sherris," replied Bess.

"Sherris!" echoed Potts, "and yet you say I can have no sack. Get me some sugar and eggs, and I'll show you how to brew the drink. I was taught the art by my friend, Ben Jonson—rare Ben—ha, ha!"

"Set the bottle down," cried Bess, angrily.

"What do you mean, woman!" said Potts, staring at her in surprise. "I told you to fetch sugar and eggs, and I now repeat the order—sugar, and half-a-dozen eggs at least."

"An ey repeat my order to yo," cried Bess, "to set the bottle down, or ey'st may ye."

"Make me! ha, ha! I like that," cried Potts. "Let me tell you, woman, I am not accustomed to be ordered in this way. I shall do no such thing. If you will not bring the eggs I shall drink the wine, neat and unsophisticate." And he filled a flagon near him.

"If yo dun, yo shan pay dearly for it," said Bess, putting aside the frying-pan and taking down the horsewhip.

"I daresay I shall," replied Potts merrily; "you hostesses generally do make one pay dearly. Very good sherris this, i' faith!—the true nutty flavour. Now do go and fetch me some eggs, my good woman. You must have plenty, with all the poultry I saw in the farm-yard; and then I'll teach you the whole art and mystery of brewing sack."

"Ey'n teach yo to dispute my orders," cried Bess. And, catching the attorney by the collar, she began to belabour him soundly with the whip.

"Holloa! ho! what's the meaning of this?" cried Potts, struggling to get free. "Assault and battery; ho!"

"Ey'n sawt an batter yo, ay, an baste yo too!" replied Bess, continuing to lay on the whip.

"Why, zounds! this passes a joke," cried the attorney. "How desperately strong she is! I shall be murdered! Help! help! The woman must be a witch."

"A witch! Ey'n teach yo' to ca' me feaw names," cried the enraged hostess, laying on with greater fury.

"Help! help!" roared Potts.

At this moment Nicholas returned from the stables, and, seeing how matters stood, flew to the attorney's assistance.

"Come, come, Bess," he cried, laying hold of her arm, "you've given him enough. What has Master Potts been about? Not insulting you, I hope?"

"Neaw, ey'd tak keare he didna do that, squoire," replied the hostess. "Ey towd him he'd get nowt boh ele here, an' he made free wi't wine bottle, so ey brought down t' whip jist to teach him manners."

"You teach me! you ignorant and insolent hussy," cried Potts, furiously; "do you think I'm to be taught manners by an overgrown Lancashire witch like you? I'll teach you what it is to assault a gentleman. I'll prefer an instant complaint against you to my singular good friend and client, Master Roger, who is in your house, and you'll soon find whom you've got to deal with—"

"Marry—kem—eawt!" exclaimed Bess; "who con it be? Ey took yo fo' one o't grooms, mon."

"Fire and fury!" exclaimed Potts; "this is intolerable. Master Nowell shall let you know who I am, woman."

"Nay, I'll tell you, Bess," interposed Nicholas, laughing. "This little gentleman is a London lawyer, who is going to Rough Lee on business with Master Roger Nowell. Unluckily, he got pitched into a quagmire in Read Park, and that is the reason why his countenance and habiliments have got begrimed."

"Eigh! ey thowt he wur i' a strawnge fettle," replied Bess; "an so he be a lawyer fro' Lunnon, eh? Weel," she added, laughing, and displaying two ranges of very white teeth, "he'll remember Bess Whitaker, t' next time he comes to Pendle Forest."

"And she'll remember me," rejoined Potts.

"Neaw more sawce, mon," cried Bess, "or ey'n raddle thy boans again."

"No you won't, woman," cried Potts, snatching up his horsewhip, which he had dropped in the previous scuffle, and brandishing it fiercely. "I dare you to touch me."

Nicholas was obliged once more to interfere, and as he passed his arms round the hostess's waist, he thought a kiss might tend to bring matters to a peaceable issue, so he took one.

"Ha' done wi' ye, squoire," cried Bess, who, however, did not look very seriously offended by the liberty.

"By my faith, your lips are so sweet that I must have another," cried Nicholas. "I tell you what, Bess, you're the finest woman in Lancashire, and you owe it to the county to get married."

"Whoy so?" said Bess.

"Because it would be a pity to lose the breed," replied Nicholas. "What say you to Master Potts there? Will he suit you?"

"He—pooh! Do you think ey'd put up wi' sich powsement os he! Neaw; when Bess Whitaker, the lonleydey o' Goldshey, weds, it shan be to a mon, and nah to a ninny-hommer."

"Bravely resolved, Bess," cried Nicholas. "You deserve another kiss for your spirit."

"Ha' done, ey say," cried Bess, dealing him a gentle tap that sounded very much like a buffet. "See how yon jobberknow is grinning at ye."

"Jobberknow and ninny-hammer," cried Potts, furiously; "really, woman, I cannot permit such names to be applied to me."

"Os yo please, boh ey'st gi' ye nah better," rejoined the hostess.

"Come, Bess, a truce to this," observed Nicholas; "the eggs and bacon are spoiling, and I'm dying with hunger. There—there," he added, clapping her on the shoulder, "set the dish before us, that's a good soul—a couple of plates, some oatcakes and butter, and we shall do."

And while Bess attended to these requirements, he observed, "This sudden seizure of poor John Law is a bad business."

"'Deed on it is, squoire," replied Bess, "ey wur quite glopp'nt at seet on him. Lorjus o' me! whoy, it's scarcely an hour sin he left here, looking os strong an os 'earty os yersel. Boh it's a kazzardly onsartin loife we lead. Here to-day an gone the morrow, as Parson Houlden says. Wall-a-day!"

"True, true, Bess," replied the squire, "and the best plan therefore is, to make the most of the passing moment. So brew us each a lusty pottle of sack, and fry us some more eggs and bacon."

And while the hostess proceeded to prepare the sack, Potts remarked to Nicholas, "I have got another case of witchcraft, squire. Mary Baldwyn, the miller's daughter, of Rough Lee."

"Indeed!" exclaimed Nicholas. "What, is the poor girl bewitched?"

"Bewitched to death—that's all," said Potts.

"Eigh—poor Meary! hoo's to be berried here this mornin," observed Bess, emptying the bottle of sherris into a pot, and placing the latter on the fire.

"And you think she was forespoken?" said Nicholas, addressing her.

"Folk sayn so," replied Bess; "boh I'd leyther howd my tung about it."

"Then I suppose you pay tribute to Mother Chattox, hostess?" cried Potts,—"butter, eggs, and milk from the farm, ale and wine from the cellar, with a flitch of bacon now and then, ey?"

"Nay, by th' maskins! ey gi' her nowt," cried Bess.

"Then you bribe Mother Demdike, and that comes to the same thing," said Potts.

"Weel, yo're neaw so fur fro' t' mark this time," replied Bess, adding eggs, sugar, and spice to the now boiling wine, and stirring up the compound.

"I wonder where your brother, the reeve of the forest, can be, Master Potts!" observed Nicholas. "I did not see either him or his horse at the stables."

"Perhaps the arch impostor has taken himself off altogether," said Potts; "and if so, I shall be sorry, for I have not done with him."

The sack was now set before them, and pronounced excellent, and while they were engaged in discussing it, together with a fresh supply of eggs and bacon, fried by the kitchen wench, Roger Nowell came out of the inner room, accompanied by Richard and the chirurgeon.

"Well, Master Sudall, how goes on your patient?" inquired Nicholas of the latter.

"Much more favourably than I expected, squire," replied the chirurgeon. "He will be better left alone for awhile, and, as I shall not quit the village till evening, I shall be able to look well after him."

"You think the attack occasioned by witchcraft of course, sir?" said Potts.

"The poor fellow affirms it to be so, but I can give no opinion," replied Sudall, evasively.

"You must make up your mind as to the matter, for I think it right to tell you your evidence will be required," said Potts. "Perhaps, you may have seen poor Mary Baldwyn, the miller's daughter of Rough Lee, and can speak more positively as to her case."

"I can, sir," replied the chirurgeon, seating himself beside Potts, while Roger Nowell and Richard placed themselves on the opposite side of the table. "This is the case I referred to a short time ago, when answering your inquiries on the same subject, Master Richard, and a most afflicting one it is. But you shall have the particulars. Six months ago, Mary Baldwyn was as lovely and blooming a lass as could be seen, the joy of her widowed father's heart. A hot-headed, obstinate man is Richard Baldwyn, and he was unwise enough to incur the displeasure of Mother Demdike, by favouring her rival, old Chattox, to whom he gave flour and meal, while he refused the same tribute to the other. The first time Mother Demdike was dismissed without the customary dole, one of his millstones broke, and, instead of taking this as a warning, he became more obstinate. She came a second time, and he sent her away with curses. Then all his flour grew damp and musty, and no one would buy it. Still he remained obstinate, and, when she appeared again, he would have laid hands upon her. But she raised her staff, and the blows fell short. 'I have given thee two warnings, Richard,' she said, 'and thou hast paid no heed to them. Now I will make thee smart, lad, in right earnest. That which thou lovest best thou shalt lose.' Upon this, bethinking him that the dearest thing he had in the world was his daughter Mary, and afraid of harm happening to her, Richard would fain have made up his quarrel with the old witch; but it had now gone too far, and she would not listen to him, but uttering some words, with which the name of the girl was mingled, shook her staff at the house and departed. The next day poor Mary was taken ill, and her father, in despair, applied to old Chattox, who promised him help, and did her best, I make no doubt—for she would have willingly thwarted her rival, and robbed her of her prey; but the latter was too strong for her, and the hapless victim got daily worse and worse. Her blooming cheek grew white and hollow, her dark eyes glistened with unnatural lustre, and she was seen no more on the banks of Pendle water. Before this my aid had been called in by the afflicted father—and I did all I could—but I knew she would die—and I told him so. The information I feared had killed him, for he fell down like a stone—and I repented having spoken. However he recovered, and made a last appeal to Mother Demdike; but the unrelenting hag derided him and cursed him, telling him if he brought her all his mill contained, and added to that all his substance, she would not spare his child. He returned heart-broken, and never quitted the poor girl's bedside till she breathed her last."

"Poor Ruchot! Robb'd o' his ownly dowter—an neaw woife to cheer him! Ey pity him fro' t' bottom o' my heart," said Bess, whose tears had flowed freely during the narration.

"He is wellnigh crazed with grief," said the chirurgeon. "I hope he will commit no rash act."

Expressions of deep commiseration for the untimely death of the miller's daughter had been uttered by all the party, and they were talking over the strange circumstances attending it, when they were roused by the trampling of horses' feet at the door, and the moment after, a middle-aged man, clad in deep mourning, but put on in a manner that betrayed the disorder of his mind, entered the house. His looks were wild and frenzied, his cheeks haggard, and he rushed into the room so abruptly that he did not at first observe the company assembled.

"Why, Richard Baldwyn, is that you?" cried the chirurgeon.

"What! is this the father?" exclaimed Potts, taking out his memorandum-book; "I must prepare to interrogate him."

"Sit thee down, Ruchot,—sit thee down, mon," said Bess, taking his hand kindly, and leading him to a bench. "Con ey get thee onny thing?"

"Neaw—neaw, Bess," replied the miller; "ey ha lost aw ey vallied i' this warlt, an ey care na how soon ey quit it mysel."

"Neigh, dunna talk on thus, Ruchot," said Bess, in accents of sincere sympathy. "Theaw win live to see happier an brighter days."

"Ey win live to be revenged, Bess," cried the miller, rising suddenly, and stamping his foot on the ground,—"that accursed witch has robbed me o' my' eart's chief treasure—hoo has crushed a poor innocent os never injured her i' thowt or deed—an has struck the heaviest blow that could be dealt me; but by the heaven above us ey win requite her! A feyther's deep an lasting curse leet on her guilty heoad, an on those of aw her accursed race. Nah rest, neet nor day, win ey know, till ey ha brought em to the stake."

"Right—right—my good friend—an excellent resolution—bring them to the stake!" cried Potts.

But his enthusiasm was suddenly checked by observing the reeve of the forest peeping from behind the wainscot, and earnestly regarding the miller, and he called the attention of the latter to him.

Richard Baldwyn mechanically followed the expressive gestures of the attorney,—but he saw no one, for the reeve had disappeared.

The incident passed unnoticed by the others, who had been, too deeply moved by poor Baldwyn's outburst of grief to pay attention to it.

After a little while Bess Whitaker succeeded in prevailing upon the miller to sit down, and when he became more composed he told her that the funeral procession, consisting of some of his neighbours who had undertaken to attend his ill-fated daughter to her last home, was coming from Rough Lee to Goldshaw, but that, unable to bear them company, he had ridden on by himself. It appeared also, from his muttered threats, that he had meditated some wild project of vengeance against Mother Demdike, which he intended to put into execution, before the day was over; but Master Potts endeavoured to dissuade him from this course, assuring him that the most certain and efficacious mode of revenge he could adopt would be through the medium of the law, and that he would give him his best advice and assistance in the matter. While they were talking thus, the bell began to toll, and every stroke seemed to vibrate through the heart of the afflicted father, who was at last so overpowered by grief, that the hostess deemed it expedient to lead him into an inner room, where he might indulge his sorrow unobserved.

Without awaiting the issue of this painful scene, Richard, who was much affected by it, went forth, and taking his horse from the stable, with the intention of riding on slowly before the others, led the animal towards the churchyard. When within a short distance of the grey old fabric he paused. The bell continued to toll mournfully, and deepened the melancholy hue of his thoughts. The sad tale he had heard held possession of his mind, and while he pitied poor Mary Baldwyn, he began to entertain apprehensions that Alizon might meet a similar fate. So many strange circumstances had taken place during the morning's ride; he had listened to so many dismal relations, that, coupled with the dark and mysterious events of the previous night, he was quite bewildered, and felt oppressed as if by a hideous nightmare, which it was impossible to shake off. He thought of Mothers Demdike and Chattox. Could these dread beings be permitted to exercise such baneful influence over mankind? With all the apparent proofs of their power he had received, he still strove to doubt, and to persuade himself that the various cases of witchcraft described to him were only held to be such by the timid and the credulous.

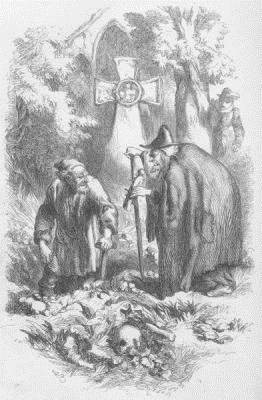

Full of these meditations, he tied his horse to a tree and entered the churchyard, and while pursuing a path shaded by a row of young lime-trees leading to the porch, he perceived at a little distance from him, near the cross erected by Abbot Cliderhow, two persons who attracted his attention. One was the sexton, who was now deep in the grave; and the other an old woman, with her back towards him. Neither had remarked his approach, and, influenced by an unaccountable feeling of curiosity, he stood still to watch their proceedings. Presently, the sexton, who was shovelling out the mould, paused in his task; and the old woman, in a hoarse voice, which seemed familiar to the listener, said, "What hast found, Zachariah?"

Richard Overhears the Mother Chattox and the Sexton.

"That which yo lack, mother," replied the sexton, "a mazzard wi' aw th' teeth in't."

"Pluck out eight, and give them me," replied the hag.

And, as the sexton complied with her injunction, she added, "Now I must have three scalps."

"Here they be, mother," replied Zachariah, uncovering a heap of mould with his spade. "Two brain-pans bleached loike snow, an the third wi' more hewr on it than ey ha' o' my own sconce. Fro' its size an shape ey should tak it to be a female. Ey ha' laid these three skulls aside fo' ye. Whot dun yo mean to do wi' 'em?"

"Question me not, Zachariah," said the hag, sternly; "now give me some pieces of the mouldering coffin, and fill this box with the dust of the corpse it contained."

The sexton complied with her request.

"Now yo ha' getten aw yo seek, mother," he said, "ey wad pray you to tay your departure, fo' the berrin folk win be here presently."

"I'm going," replied the hag, "but first I must have my funeral rites performed—ha! ha! Bury this for me, Zachariah," she said, giving him a small clay figure. "Bury it deep, and as it moulders away, may she it represents pine and wither, till she come to the grave likewise!"

"An whoam doth it represent, mother?" asked the sexton, regarding the image with curiosity. "Ey dunna knoa the feace?"

"How should you know it, fool, since you have never seen her in whose likeness it is made?" replied the hag. "She is connected with the race I hate."

"Wi' the Demdikes?" inquired the sexton.

"Ay," replied the hag, "with the Demdikes. She passes for one of them—but she is not of them. Nevertheless, I hate her as though she were."

"Yo dunna mean Alizon Device?" said the sexton. "Ey ha' heerd say hoo be varry comely an kind-hearted, an ey should be sorry onny harm befell her."

"Mary Baldwyn, who will soon lie there, was quite as comely and kind-hearted as Alizon," cried the hag, "and yet Mother Demdike had no pity on her."

"An that's true," replied the sexton. "Weel, weel; ey'n do your bidding."

"Hold!" exclaimed Richard, stepping forward. "I will not suffer this abomination to be practised."

"Who is it speaks to me?" cried the hag, turning round, and disclosing the hideous countenance of Mother Chattox. "The voice is that of Richard Assheton."

"It is Richard Assheton who speaks," cried the young man, "and I command you to desist from this wickedness. Give me that clay image," he cried, snatching it from the sexton, and trampling it to dust beneath his feet. "Thus I destroy thy impious handiwork, and defeat thy evil intentions."

"Ah! think'st thou so, lad," rejoined Mother Chattox. "Thou wilt find thyself mistaken. My curse has already alighted upon thee, and it shall work. Thou lov'st Alizon.—I know it. But she shall never be thine. Now, go thy ways."

"I will go," replied Richard—"but you shall come with me, old woman."

"Dare you lay hands on me?" screamed the hag.

"Nay, let her be, mester," interposed the sexton, "yo had better."

"You are as bad as she is," said Richard, "and deserve equal punishment. You escaped yesterday at Whalley, old woman, but you shall not escape me now."

"Be not too sure of that," cried the hag, disabling him for the moment, by a severe blow on the arm from her staff. And shuffling off with an agility which could scarcely have been expected from her, she passed through a gate near her, and disappeared behind a high wall.

Richard would have followed, but he was detained by the sexton, who besought him, as he valued his life, not to interfere, and when at last he broke away from the old man, he could see nothing of her, and only heard the sound of horses' feet in the distance. Either his eyes deceived him, or at a turn in the woody lane skirting the church he descried the reeve of the forest galloping off with the old woman behind him. This lane led towards Rough Lee, and, without a moment's hesitation, Richard flew to the spot where he had left his horse, and, mounting him, rode swiftly along it.

CHAPTER VI.—THE TEMPTATION

Shortly after Richard's departure, a round, rosy-faced personage, whose rusty black cassock, hastily huddled over a dark riding-dress, proclaimed him a churchman, entered the hostel. This was the rector of Goldshaw, Parson Holden, a very worthy little man, though rather, perhaps, too fond of the sports of the field and the bottle. To Roger Nowell and Nicholas Assheton he was of course well known, and was much esteemed by the latter, often riding over to hunt and fish, or carouse, at Downham. Parson Holden had been sent for by Bess to administer spiritual consolation to poor Richard Baldwyn, who she thought stood in need of it, and having respectfully saluted the magistrate, of whom he stood somewhat in awe, and shaken hands cordially with Nicholas, who was delighted to see him, he repaired to the inner room, promising to come back speedily. And he kept his word; for in less than five minutes he reappeared with the satisfactory intelligence that the afflicted miller was considerably calmer, and had listened to his counsels with much edification.

"Take him a glass of aquavitæ, Bess," he said to the hostess. "He is evidently a cup too low, and will be the better for it. Strong water is a specific I always recommend under such circumstances, Master Sudall, and indeed adopt myself, and I am sure you will approve of it.—Harkee, Bess, when you have ministered to poor Baldwyn's wants, I must crave your attention to my own, and beg you to fill me a tankard with your oldest ale, and toast me an oatcake to eat with it.—I must keep up my spirits, worthy sir," he added to Roger Nowell, "for I have a painful duty to perform. I do not know when I have been more shocked than by the death of poor Mary Baldwyn. A fair flower, and early nipped."

"Nipped, indeed, if all we have heard be correct," rejoined Newell. "The forest is in a sad state, reverend sir. It would seem as if the enemy of mankind, by means of his abominable agents, were permitted to exercise uncontrolled dominion over it. I must needs say, the forlorn condition of the people reflects little credit on those who have them in charge. The powers of darkness could never have prevailed to such an extent if duly resisted."