Полная версия

Полная версияThe Empire of Austria; Its Rise and Present Power

"We are sure, therefore, that at the meeting of the ensuing diet, your majesty will not confine yourself to the objects mentioned in your rescript, but will also restore our freedom to us, in like manner as to the Belgians, who have conquered theirs with the sword. It would be an example big with danger, to teach the world that a people can only protect or regain their liberties by the sword and not by obedience."

But Leopold, trembling at the progress which freedom was making in France, determined to crush this spirit with an iron heel. Their petition was rejected with scorn and menace.

With great splendor Leopold entered Presburg, and was crowned King of Hungary on the 10th of November, 1790. Having thus silenced the murmurs in Hungary, and established his authority there, he next turned his attention to the recovery of the Netherlands. The people there, breathing the spirit of French liberty, had, by a simultaneous rising, thrown off the detestable Austrian yoke. Forty-five thousand men were sent to effect their subjugation. On the 20th of November, the army appeared before Brussels. In less than one year all the provinces were again brought under subjection to the Austrian power.

Leopold, thus successful, now turned his attention to France. Maria Antoinette was his sister. He had another sister in the infamous Queen Caroline of Naples. The complaints which came incessantly from Versailles and the Tuilleries filled his ear, touched his affections, and roused his indignation. Twenty-five millions of people had ventured to assert their rights against the intolerable arrogance of the French court. Leopold now gathered his armies to trample those people down, and to replace the scepter of unlimited despotism in the hands of the Bourbons. With sleepless zeal Leopold coöperated with nearly all the monarchs in Europe, in combining a resistless force to crush out from the continent of Europe the spirit of popular liberty. An army of ninety thousand men was raised to coöperate with the French emigrants and all the royalists in France. The king was to escape from Paris, place himself at the head of the emigrants, amounting to more than twenty thousand, rally around his banners all the advocates of the old regime, and then, supported by all the powers of combined Europe, was to march upon Paris, and take a bloody vengeance upon a people who dared to wish to be free. The arrest of Louis XVI. at Varennes deranged this plan. Leopold, alarmed not only by the impending fate of his sister, but lest the principles of popular liberty, extending from France, should undermine his own throne, wrote as follows to the King of England:

"I am persuaded that your majesty is not unacquainted with the unheard of outrage committed by the arrest of the King of France, the queen my sister and the royal family, and that your sentiments accord with mine on an event which, threatening more atrocious consequences, and fixing the seal of illegality on the preceding excesses, concerns the honor and safety of all governments. Resolved to fulfill what I owe to these considerations, and to my duty as chief of the German empire, and sovereign of the Austrian dominions, I propose to your majesty, in the same manner as I have proposed to the Kings of Spain, Prussia and Naples, as well as to the Empress of Russia, to unite with them, in a concert of measures for obtaining the liberty of the king and his family, and setting bounds to the dangerous excesses of the French Revolution."

The British people nobly sympathized with the French in their efforts at emancipation, and the British government dared not then shock the public conscience by assailing the patriots in France. Leopold consequently turned to Frederic William of Prussia, and held a private conference with him at Pilnitz, near Dresden, in Saxony, on the 27th of August, 1791. The Count d'Artois, brother of Louis XVI., and who subsequently ascended the French throne as Charles X., joined them in this conference. In the midst of these agitations and schemes Leopold II. was seized with a malignant dysentery, which was aggravated by a life of shameless debauchery, and died on the 1st of March, 1792, in the forty-fifth year of his age, and after a reign of but two years.

Leopold has the reputation of having been, on the whole, a kind-hearted man, but his court was a harem of unblushing profligacy. His broken-hearted wife was compelled to submit to the degradation of daily intimacy with the mistress of her husband. Upon one only of these mistresses the king lavished two hundred thousand dollars in drafts on the bank of Vienna. The sums thus infamously squandered were wrested from the laboring poor. His son, Francis II., who succeeded him upon the throne, was twenty-two years of age. In most affecting terms the widowed queen entreated her son to avoid those vices of his father which had disgraced the monarchy and embittered her whole life.

The reign of Francis II. was so eventful, and was so intimately blended with the fortunes of the French Revolution, the Consulate and the Empire, that the reader must be referred to works upon those subjects for the continuation of the history. During the wars with Napoleon Austria lost forty-five thousand square miles, and about three and a half millions of inhabitants. But when at length the combined monarchs of Europe triumphed over Napoleon, the monarch of the people's choice, and, in the carnage of Waterloo, swept constitutional liberty from the continent, Austria received again nearly all she had lost.

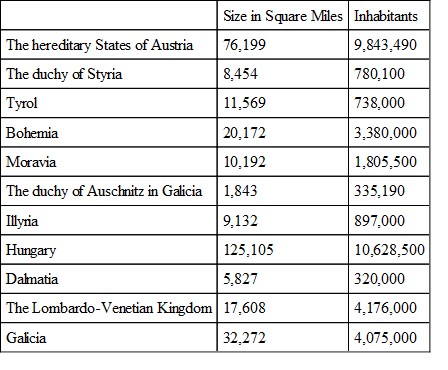

This powerful empire, as at present constituted, embraces:

Thus the whole Austrian monarchy contains 256,399 square miles, and a population which now probably exceeds forty millions. The standing army of this immense monarchy, in time of peace, consists of 271,400 men, which includes 39,000 horse and 17,790 artillery. In time of war this force can be increased to almost any conceivable amount.

Thus slumbers this vast despotism, in the heart of central Europe, the China of the Christian world. The utmost vigilance is practiced by the government to seclude its subjects, as far as possible, from all intercourse with more free and enlightened nations. The government is in continual dread lest the kingdom should be invaded by those liberal opinions which are circulating in other parts of Europe. The young men are prohibited, by an imperial decree, from leaving Austria to prosecute their studies in foreign universities. "Be careful," said Francis II. to the professors in the university at Labach, "not to teach too much. I do not want learned men in my kingdom; I want good subjects, who will do as I bid them." Some of the wealthy families, anxious to give their children an elevated education, and prohibited from sending them abroad, engaged private tutors from France and England. The government took the alarm, and forbade the employment of any but native teachers. The Bible, the great chart of human liberty, all despots fear and hate. In 1822 a decree was issued by the emperor prohibiting the distribution of the Bible in any part of the Austrian dominions.

The censorship of the press is rigorous in the extreme. No printer in Austria would dare to issue the sheet we now write, and no traveler would be permitted to take this book across the frontier. Twelve public censors are established at Vienna, to whom every book published within the empire, whether original or reprinted, must be referred. No newspaper or magazine is tolerated which does not advocate despotism. Only those items of foreign intelligence are admitted into those papers which the emperor is willing his subjects should know. The freedom of republican America is carefully excluded. The slavery which disgraces our land is ostentatiously exhibited in harrowing descriptions and appalling engravings, as a specimen of the degradation to which republican institutions doom the laboring class.

A few years ago, an English gentleman dined with Prince Metternich, the illustrious prime minister of Austria, in his beautiful castle upon the Rhine. As they stood after dinner at one of the windows of the palace, looking out upon the peasants laboring in the vineyards, Metternich, in the following words, developed his theory of social order:

"Our policy is to extend all possible material happiness to the whole population; to administer the laws patriarchaly; to prevent their tranquility from being disturbed. Is it not delightful to see those people looking so contented, so much in the possession of what makes them comfortable, so well fed, so well clad, so quiet, and so religiously observant of order? If they are injured in persons or property, they have immediate and unexpensive redress before our tribunals, and in that respect, neither I, nor any nobleman in the land, has the smallest advantage over a peasant."

But volcanic fires are heaving beneath the foundations of the Austrian empire, and dreadful will be the day when the eruption shall burst forth.

1

Cæsar Borgia, who has filled the world with the renown of his infamy, was the illegitimate son of Alexander VI., and of a Roman lady named Yanozza.