Полная версия

Полная версияRollo in Scotland

After supper Mr. George proposed to the boys that they should take a walk about the village, as it was only nine o'clock, and it would not be dark for another hour. So they went out and walked through the street, back and forth. The houses were built of a sort of gray stone, and they stood all close together in rows, one on each side of the street, with nothing green around them or near them. The street thus presented a very gray, sombre, and monotonous appearance; very different from the animated and cheerful aspect of American villages, with their white houses and green blinds, and pretty yards and gardens, enclosed with ornamental palings. The boys wished to go down to the shore of the loch; but as they did not see the water any where, Mr. George said he thought it would be too far. So they went back to the inn.

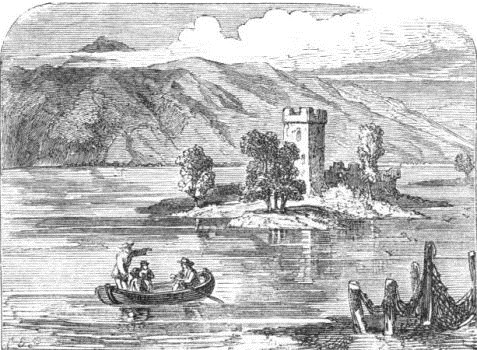

The next morning, after breakfast, they set out to go and visit the castle. A boy went with them from the inn to show them the way. He led them down the street of the village, to a house where he said the man lived who "had the fishing" of the loch. It seems that the loch, including the right to fish in it, is private property, and that the owner of it lets the fishing to a man in the village, and that he keeps a boat to take visitors out to see the castle. So they went to the house where this man lived. They explained what they wanted at the door, and pretty soon a boatman came out, and went with them to the shore of the pond. The way was through a wide green field, that had been formed out of the bottom of the loch, by drawing off the water. When they came to the shore they found a small pier there, with a boat fastened to it. There was a small boat house near the pier. The boatman brought some oars out of the boat house, and put them in the boat, and then they all got in.

The morning was calm, and the loch was very smooth, and the boat glided along very gently over the water. There was a great curve in the shore near the pier, so that for some time the boat, though headed directly for the island, which was in the middle of the loch, moved parallel to the shore, and very near it. There was a smooth and beautiful green field all the way along the shore, which sloped down gently to the margin of the water. Beyond this field, which was not wide, there was a road, and beyond the road there was a wall. Over the wall were to be seen the trees of a great park; and presently the boat came opposite to the gateway, through which the boys could see, as they sailed by, a large and handsome stone house, or castle. The boatman said it was not inhabited, because the owner of it was not yet of age.

After passing the house they came, before long, to the end of these grounds, which formed a point projecting into the lake. There was a small and very ancient-looking burying ground on the point. This burying ground will be referred to hereafter; so do not forget it.

After passing this point of land, the boat, in her course towards the castle, came out into the open loch—the little island on which the ruins of the castle stand being in full view.

There was, however, yet a pretty broad sheet of open water to pass before reaching the island.

LOCH LEVEN.

"Now we have passed Cape Race," said Waldron, "and are striking out into the open sea."

Cape Race is the southern cape of Newfoundland, and is the last land to be seen on the American coast, in crossing the Atlantic.

After about a quarter of an hour, the boat began to approach the shores of the little island. And now the great square tower, and the rampart wall connected with it, came plainly in sight. There were a few very large and old trees overhanging the ruins, and all the rest of the island was covered with a dense grove of young trees. The boat came up to the land, and Mr. George and the boys stepped out of it upon a sort of jetty, formed of stones loosely thrown together. There was a path leading through the grass, and among the trees, towards the ruins of the castle.

The castle consisted, when it was entire, of a square area enclosed in a high wall, with various buildings along the inner side of it. The principal of these buildings was the square tower. This was in one corner of the enclosure. At the opposite corner of the enclosure were the ruins of a smaller tower, hexagonal in its form. The square tower contained the principal apartments occupied by the family that resided in the castle. The hexagonal one contained the rooms where Queen Mary was imprisoned.

Then, besides these structures, there were several other buildings within the area, though they are now gone almost entirely to ruin. There was a chapel, for religious services and worship; there were ovens for baking, and a brewery for brewing beer. The guide showed Mr. George and the boys the places where these buildings stood; though nothing was left of them now but the rude ranges of stone which marked the foundations of them. Indeed, throughout the whole interior of the area enclosed by the castle wall there was nothing to be seen but stones and heaps of rubbish, all overgrown with rank grass, and tall wild-flowers, and overshadowed by the wide-spreading limbs and dense foliage of several enormous trees, that had by chance sprung up since the castle went to ruin. It was a very mournful spectacle.

The boys walked directly across the area, towards the hexagonal tower, in order to see the place where Queen Mary escaped by climbing out of the window.

Mr. George had thought that Waldron would not succeed in obtaining any satisfactory information from the guide in respect to the circumstances of Queen Mary's escape; for, generally, the guides who show these old places in England and Scotland know little more than a certain lesson, which they have learned by rote. But the guides who show the Castle of Loch Leven seem to me exceptions to this rule. I have visited the place two or three times, at intervals of many years, and the guides who have conducted me to the spot have always been very intelligent and well-informed young men, and have seemed to possess a very clear and comprehensive understanding of the events of Queen Mary's life. At any rate, the guide in this instance gave Waldron and Rollo a very good account of the escape; separating in his narrative, in a very discriminating manner, those things which are known, on good historical evidence, to be true, from those which rest only on the authority of traditionary legends. He gave his account, too, in a very gentle tone of voice, and with a Scotch accent, which seemed so appropriate to the place and to the occasion that it imparted to his conversation a peculiar charm.

"The country was divided in those days," said he, "and some of the nobles were for the poor queen, and some were against her. The owner of this castle was Lady Douglass, and she was against her; and so they sent Mary here, for Lady Douglass to keep her safely, while they arranged a new government.

"But she made her escape by this window, which I will show ye."

So saying, the guide led the way up two or three old, time-worn, and dilapidated steps, into the hexagonal tower. The tower was small—being, apparently, not more than twelve feet diameter within. The floors, except the lower one, and also the roof, were entirely gone, so that as soon as you entered you could look up to the sky.

The walls were very thick, so that there was room, not only for deep fireplaces, but also for closets and for a staircase, in them. You could see the openings for these closets, and also various loopholes and windows, at different heights. The top of the wall was all broken away, and so were the sills of the windows; and little tufts of grass and of wall flowers were to be seen, here and there, growing out of clefts and crevices. There were also rows of small square holes to be seen, at different heights, where the ends of the timbers had been inserted, to form the floors of the several stories.

"This was the window where she is supposed to have got out," said the guide.

So saying, he pointed to a large opening in the wall, on the outer side, where there had once, evidently, been a window.

The boys went to the place, and looked out. They saw beneath the window a smooth, green lawn, with the young trees which had been planted growing luxuriantly upon it.

"I suppose," said Mr. George, "that before the lake was lowered the water came up close under the window."

"Yes, sir," said the guide; "and if you stand upon the sill, and look down, you will see a course of projecting stone at the foot of the wall which was laid to meet the wash of the water."

"Let me see," said Waldron, eagerly.

So saying, Waldron advanced by the side of Mr. George, and looked down. By leaning over pretty far he could see the course of stone very distinctly that the guide had referred to.

"Who brought the boat here for Mary to go away in?" asked Waldron.

"Young Douglass," said the guide, "Lady Douglass's son. He was a young lad, only eighteen years old. His mother was Queen Mary's enemy; but he pitied her, and became her friend, and he devised this way to assist her to escape. There was a plan devised before this, by his brother. His name was George Douglass. The one who came in the boat was William. George's plan was for Mary to go on shore in the disguise of a laundress. The laundress came over to the island from the shore in a boat, to bring the linen; and while she was in Mary's room Mary exchanged clothes with her, and attempted to go on shore in the boat with the empty basket. But the boatmen happened to notice her hand, which was very delicate and white, and they knew that such a hand as that could never belong to a real laundress. So they made her lift up her veil, and thus she was discovered."

"That was very curious," said Waldron.

"It is supposed," said the guide, "that this floor, where we stand, was Mary's drawing room, and the floor above was her bed chamber. The staircase where she went up is there, in the wall."

"Let's go up," said Rollo.

So Rollo and Waldron went up the stairway. It was very narrow, and rather steep, and the steps were much worn away. When the boys reached the top they came to an opening, through which they could look down to where Mr. George and the guide were standing below; though, of course, they could not go out; for the floor in the second story was entirely gone.

"There was a room above the bed chamber," said the guide, "as we see by the windows and the fireplace, but there was no stairway to it from Queen Mary's apartments. The only access to it was through that door, which leads in from the top of the rampart wall. And there is another room below, and partly under ground. That is the room where Walter Scott represents the false keys to have been forged."

"What false keys?" asked Waldron.

"Why, the story is," said the guide, "that young Douglass had false keys made, to resemble the true ones as nearly as possible, so as to deceive his mother. He then contrived to get the true ones away from his mother, and put the false ones in their place. I will show you where he did this, and explain how he did it, when we go into the square tower."

"Let us go now," said Waldron.

So they all went across the court yard, and approached the square tower. The guide explained to the boys that formerly the entrance was in the second story, through an opening in the wall, which he showed them. The way to get up to this opening was by a step ladder, which could be let down or drawn up by the people within, by means of chains coming down from a window above. The step ladder was, of course, entirely gone; but deep grooves were to be seen in the sill of the upper window, which had been worn by the chains in letting down and drawing up the ladder.

To accommodate modern visitors a flight of loose stone steps had been laid outside the square tower, leading to a window in the lower story of it. Mr. George and the boys ascended these steps and went in. The lower room was the kitchen, and they were all much interested and amused in looking at the very strange and curious fixtures and contrivances which remained there—the memorials of the domestic usages of those ancient times.

In a corner of the room was a flight of steps, built in the thickness of the wall, leading to the story above. This was the dining room and parlor of the castle.

"It was here," said the guide, "according to the story of Walter Scott, that Douglass contrived to get possession of the castle keys. There was a window on one side of the room, from which there was a view, across the water of the lake, of the burying ground already mentioned. Lady Douglass, like almost every body else in those times, was somewhat superstitious, and William arranged it with a page that he was to pretend to see what was called a corpse light, moving about in the burying ground; and while his mother went to see, he shifted the keys which she had left upon the table, taking the true ones himself, and leaving the false ones in their place.

"That is the story which Sir Walter Scott relates," said the guide; "but I am not sure that there is any historical authority for it."

"And what became of Queen Mary, after she escaped in the boat?" asked Waldron.

"O, there were several of her friends," said the guide, "waiting for her on the shore of the loch where she was to land, and they hurried her away on horseback to a castle in the south of Scotland, and there they gathered an army for her, to defend her rights."

After this the boys looked down through a trap door, which led to a dark dungeon, where it is supposed that prisoners were sometimes confined. They rambled about the ruins for some time longer, and then they returned to the boat, and came back to the shore. When they arrived at the pier they paid the boatman his customary fee, which was about a dollar and a quarter, and then began to walk up towards the inn.

"Well, boys," said Mr. George, "how did you like it?"

"Very much indeed," said Waldron. "It is the best old castle I ever saw."

"You will like the Palace of Holyrood better, I think," said Mr. George.

"Where is that?" asked Rollo.

"At Edinburgh," said Mr. George. "It is the place where Mary lived. We shall see the little room there where they murdered her poor secretary, David Rizzio."

"What did they murder him for?" asked Waldron.

"O, you will see when you come to read the history," said Mr. George. "It is a very curious story."

Chapter XII.

Edinburgh

From Loch Leven Castle our party returned in the coach to the railway station, and thence proceeded to Edinburgh. They crossed the Frith of Forth by a ferry, at a place where it was about five miles wide.

Edinburgh is considered one of the most remarkable cities in the world, in respect to the picturesqueness of its situation. It stands upon and among a very extraordinary group of steep hills and deep valleys. A part of it is very ancient, and another part is quite modern, so that in describing it, it is often said that it consists of the old town and the new town. But it seems to me that a more obvious distinction would be, to divide it into the upper town and the lower town; for there are almost literally two towns, one upon the top of the other. The upper town is built on the hills. The lower one lies in the valleys. The streets of the upper town are connected by bridges; and when you stand upon one of these bridges, and look down, you see a street instead of a river below, with ranges of strange and antique-looking buildings on each side, for banks, and a current of men, women, and children flowing along, instead of water.

The different portions of the lower town, on the other hand, are connected by tunnels and arched passage ways under the bridges above described; and then there are flights of steps, and steep winding or zigzag paths, leading up and down between the lower streets and the upper, in the most surprising manner.

There are twenty places, more or less, in the town, where you have two streets crossing each other at right angles, one fifty feet below the other, with an immense traffic of horses, carriages, carts, and foot passengers, going to and fro in both of them. You come upon these places sometimes very unexpectedly. You are walking along on the pavement of a crowded street, when you come suddenly upon the break, or interruption in the line of building on each side. The space is occupied by a parapet, or by a high iron balustrade. You stop to look over, expecting to see a river or a canal; instead of which, you find yourself looking down into the chimneys of four-story houses bordering another street below you, which is so far down that the people walking in it, and the children playing on the sidewalk, look like pygmies.

At one place, in looking over the parapet of such a bridge, you see a vast market, with carts filled with vegetables standing all around it. At another, you behold a great railway station, with crowds of passengers on the platforms, and trains of cars coming and going; at another, a range of beautiful gardens and pleasure grounds, with ladies and gentlemen walking in them, or sitting on seats under the trees, and children trundling their hoops, or rolling their balls, over the smooth gravel walks.

Sometimes a street of the upper town, running along on the crest or side of a hill, lies parallel with one in the lower town, that extends below it in the valley. In this case the block of houses that comes between will be very high indeed on the side towards the lower street; so that you see buildings sometimes eight or ten stories high at one front, and only four or five on the other. These structures consist, in fact, of two houses, one on top of the other; the entrances to the lower house being from one of the streets of the lower town, and those leading to the one on the top being from a street in the upper town.

The reason why Edinburgh was built in this extraordinary position was, because it had its origin in a castle on a rock. This rock, with the castle that crowns the summit of it, rears its lofty head now in the very centre of the town, with deep valleys all around it. This rock, or rather rocky hill,—for it is nearly a mile in circumference,—is very steep on all sides but one. On that side there is a gradual slope, a mile or more in length, leading down to the level country. A great many centuries ago the military chieftains of those days built the castle on the hill. About the same time the monks built a monastery on the level ground at the foot of the long slope leading down from the castle. The rocky hill was an excellent place for the castle, for there was a hundred feet of almost perpendicular precipice on all sides but one, and on that side there was a convenient slope for the people who lived in the castle to go up and down; and thus, by fortifying this side, and making slight walls on all the other sides, the whole place would be very secure. The level ground below, too, was a very good place for the monastery or abbey; for it was easily accessible from all the country around, and was, moreover, in the midst of a region of fertile land, easy for the lay brethren to till. There was no necessity that the abbey should be in a fortified place, for such establishments were considered sacred in those days, and even in the most furious wars they were seldom molested.

In process of time a palace was built by the side of the abbey. This palace and a part of the ruins of the abbey still remain. Of course, when the palace was built, a town would gradually grow up near it. Many noblemen of the realm came and built houses along the street which led from the palace up to the castle—now called High Street. The fronts of these houses were on the street, and the gardens behind them extended down the slopes of the ridge on both sides, into the deep valleys that bordered them. Little lanes were left between these houses, leading down the slopes; but they were closed at the bottom by a wall, which was built along at the foot of the descent on each side, and formed the enclosure of the town.

In process of time the town extended down into these valleys, and then to the other hills beyond them. Then bridges were built here and there across the valleys, to lead from one hill to another, and tunnels and other subterranean passages were made, to connect one valley with another, until, finally, the town assumed the very extraordinary appearance which it now presents to view. Besides the hills within the town, there are some very large and high ones just beyond the limits of it. One of these is called Arthur's Seat, and is quite a little mountain. The path leading to the top of it runs along upon the crest of a remarkable range of precipices, called Salisbury Crags. These precipices face towards the town, and together with the lofty summit of Arthur's Seat, which rises immediately behind them, form a very conspicuous object from a great many points of view in and around the town.

Unfortunately, however, none of this exceedingly picturesque scenery could be seen to advantage by our party, on the day that they arrived in Edinburgh, on account of the rain. All that they knew was, that they came into the town by a tunnel, and when they left the train at the station they were at the bottom of so deep a valley that they had to ascend to the third story before they could get out, and then they had to go up a hill to get to the street in which the hotel was situated.

The name of this street was Prince's Street. It lay along the margin of one of the Edinburgh hills, overlooking a long valley, which extended between it and Castle Hill, on which the town was first built. There were no houses in this street on the side towards the valley, but there were several bridges leading across the valley, as if it had been a river. Beyond the valley were to be seen the backs of the houses in High Street, which looked like a range of cliffs, divided by vertical chasms and seams, and blackened by time. At one end of the hill was the castle rock, crowned with the towers, and bastions, and battlemented walls of the ancient fortress.

The boys went directly to their rooms when they arrived at the hotel, and while Mr. George was unstrapping and opening his valise, Waldron and Rollo went to look out at the window, to see what they could see.

"Well, boys," said Mr. George, "how does it look?"

"It looks rainy," said Rollo. "But we can see something."

"What can you see?" asked Mr. George.

"We can see the castle on the hill," said Rollo. "At least, I suppose it is the castle. It is right before us, across the valley, with a precipice of rocks all around it, on every side but one. There is a zigzag wall running round on the top of the precipices, close to the brink of them. If a man could climb up the rocks he could not get in, after all."

"And what is there inside the wall?" asked Mr. George.

"O, there are ever so many buildings," said Rollo—"great stone forts, and barracks, and bastions, rising up one above another, and watch towers on the angles of the walls. I can see one, two, three watch towers. I should like to be in one of them. I could look over the whole city, and all the country around.

"I can see some portholes, with guns pointing out,—and—O, and now I see a monstrous great gun, looking over this way, from one of the highest platforms. I believe it is a gun."

"I suppose it must be Mons Meg," said Mr. George.

"Mons Meg?" repeated Rollo. "I'll get a glass and see."

"Yes," said Mr. George. "There is a very famous old gun in Edinburgh Castle, named Mons Meg. I think it may be that."

"I can't see very plain," said Rollo, "the air is so thick with the rain; but it is a monstrous gun."

Just at this time the waiter came into the room to ask the party if they would have any thing to eat.

"Yes," said Mr. George, "we will. Go down with the waiter, boys, and see what there is, and order a good supper. I will come down in fifteen minutes."

So the boys went down, and in fifteen minutes Mr. George followed. He found the supper table ready in a corner of the coffee room, and Rollo sitting by it alone.

"Where is Waldron?" asked Mr. George.

"He's gone to the circulating library," said Rollo.

"The circulating library?" repeated Mr. George.

"He has gone to get a book about the history of Scotland," said Rollo. "We have been reading in the guide book about the castle, and Waldron says he wants to know something more about the kings, and the battles they fought."