Полная версия

Полная версияRollo at Work

He saw them wheel in one or two loads of stones, and told them he thought they were doing very well.

“We have earned one cent already,” said Rollo.

“How,” said Jonas; “is your father going to pay you for your work?”

“Yes,” said Rollo, “a cent for every two loads we put in.”

“Then you must keep tally,” said Jonas.

“Tally,” said Rollo, “what is tally?”

“Tally is the reckoning. How are you going to remember how many loads you wheel in?”

“O, we can remember easily enough,” said Rollo: “we will count them as we go along.”

“That will never do,” said Jonas. “You must mark them down with a piece of chalk on your wheelbarrow.”

So saying, Jonas fumbled in his pockets, and drew out a small, well-worn piece of chalk, and then tipped up Rollo's wheelbarrow, saying,

“How many loads do you say you have carried already?”

“Two,” said Rollo.

“Two,” repeated Jonas; and he made two white marks with his chalk on the side of the wheelbarrow.

“There!” said he.

“Mark mine,” said James; “I have wheeled two loads.”

Jonas marked them, and then laid the chalk down upon a flat stone by the side of the path, and told the boys that they must stop after every load, and make a mark, and that would keep the reckoning exact.

Jonas then left them, and the boys went on with their work. They wheeled ten loads of stones apiece, and by that time had the bottom of the path all covered, so that they could not wheel any more, without the long boards. They went up and got the boards, and laid them down as Jonas had described, and then went on with their wheeling.

At first, James kept constantly stopping, either to play, or to hear Rollo talk; for they kept the wheelbarrows together all the time, as Jonas had recommended. At such times, Rollo would remind him of his work, for he had himself learned to work steadily. They were getting on very finely, when, at length, they heard a bell ringing at the house.

This bell was to call them home; for as Rollo and Jonas were often away at a little distance from the house, too far to be called very easily, there was a bell to ring to call them home; and Mary, the girl, had two ways of ringing it—one way for Jonas, and another for Rollo.

The bell was rung now for Rollo; and so he and James walked along towards home. When they had got about half way, they saw Rollo's father standing at the door, with a basket in his hand; and he called out to them to bring their wheelbarrows.

So the boys went back for their wheelbarrows.

When they came up a second time with their wheelbarrows before them, he asked how they had got along with their work.

“O, famously,” said Rollo. “There is the tally,” said he, turning up the side of the wheelbarrow towards his father, so that he could see all the marks.

“Why, have you wheeled as many loads as that?” said his father.

“Yes, sir,” said Rollo, “and James just as many too.”

“And were they all good loads?”

“Yes, all good, full loads.”

“Well, you have done very well. Count them, and see how many there are.”

The boys counted them, and found there were fifteen.

“That is enough to come to seven cents, and one load over,” said Rollo's father; and he took out his purse, and gave the boys seven cents each, that is, a six-cent piece in silver, and one cent besides. He told them they might keep the money until they had finished their work, and then he would tell them about purchasing something with it.

“Now,” said he, “you can rub out the tally—all but one mark. I have paid you for fourteen loads, and you have wheeled in fifteen; so you have one mark to go to the new tally. You can go round to the shed, and find a wet cloth, and wipe out your marks clean, and then make one again, and leave it there for to-morrow.”

“But we are going right back now,” said Rollo.

“No,” said his father; “I don't want you to do any more to-day.”

“Why not, father? We want to, very much.”

“I cannot tell you why, now; but I choose you should not. And, now, here is a luncheon for you in this basket. You may go and eat it where you please.”

Rights Defined

So the boys took the basket, and, after they had rubbed out the tally, they went and sat down by their sand-garden, and began to eat the bread and cheese very happily together.

After they had finished their luncheon, they went and got a watering-pot, and began to water their sand-garden, and, while doing it, began to talk about what they should buy with their money. They talked of several things that they should like, and, at last, Rollo said he meant to buy a bow and arrow with his.

“A bow and arrow?” said James. “I do not believe your father will let you.”

“Yes, he will let me,” said Rollo. “Besides, it is our money, and we can do what we have a mind to with it.”

“I don't believe that,” said James.

“Why, yes, we can,” said Rollo.

“I don't believe we can,” said James.

“Well, I mean to go and ask my father,” said Rollo, “this minute.”

So he laid down the watering-pot, and ran in, and James after him. When they got into the room where his father was, they came and stood by his side a minute, waiting for him to be ready to speak to them.

Presently, his father laid down his pen, and said,

“What, my boys!”

“Is not this money our own?” said Rollo.

“Yes.”

“And can we not buy what we have a mind to with it?”

“That depends upon what you have a mind to buy.”

“But, father, I should think that, if it was our own, we might do any thing with it we please.”

“No,” said his father, “that does not follow, at all.”

“Why, father,” said Rollo, looking disappointed, “I thought every body could do what they pleased with their own things.”

“Whose hat is that you have on? Is it James's?”

“No, sir, it is mine.”

“Are you sure it is your own?”

“Why, yes, sir,” said Rollo, taking off his hat and looking at it, and wondering what his father could mean.

“Well, do you suppose you have a right to go and sell it?”

“No, sir,” said Rollo.

“Or go and burn it up?”

“No, sir.”

“Or give it away?”

“No, sir.”

“Then it seems that people cannot always do what they please with their own things.”

“Why, father, it seems to me, that is a very different thing.”

“I dare say it seems so to you; but it is not—it is just the same thing. No person can do anything they please with their property. There are limits and restrictions in all cases. And in all cases where children have property, whether it is money, hats, toys, or any thing, they are always limited and restricted to such a use of them as their parents approve. So, when I give you money, it becomes yours just as your clothes, or your wheelbarrow, or your books, are yours. They are all yours to use and to enjoy; but in the way of using them and enjoying them, you must be under my direction. Do you understand that?”

“Why, yes, sir,” said Rollo.

“And does it not appear reasonable?”

“Yes, sir, I don't know but it is reasonable. But men can do anything they please with their money, can they not?”

“No,” said his father; “they are under various restrictions made by the laws of the land. But I cannot talk any more about it now. When you have finished your work, I will talk with you about expending your money.”

The boys went on with their work the next day, and built the causey up high enough with stones. They then levelled them off, and began to wheel on the gravel. Jonas made each of them a little shovel out of a shingle; and, as the gravel was lying loose under a high bank, they could shovel it up easily, and fill their wheelbarrows. The third day they covered the stones entirely with gravel, and smoothed it all over with a rake and hoe, and, after it had become well trodden, it made a beautiful, hard causey; so that now there was a firm and dry road all the way from the house to the watering-place at the brook.

Calculation

On counting up the loads which it had taken to do this work, Rollo's father found that he owed Rollo twenty-three cents, and James twenty-one. The reason why Rollo had earned the most was because, at one time, James said he was tired, and must rest, and, while he was resting, Rollo went on wheeling.

James seemed rather sorry that he had not got as many cents as Rollo.

“I wish I had not stopped to rest,” said he.

“I wish so too,” said Rollo; “but I will give you two of my cents, and then I shall have only twenty-one, like you.”

“Shall we be alike then?”

“Yes,” said Rollo; “for, you see, two cents taken away from twenty-three, leaves twenty-one, which is just as many as you have.”

“Yes, but then I shall have more. If you give me two, I shall have twenty-three.”

“So you will,” said Rollo; “I did not think of that.”

The boys paused at this unexpected difficulty; at last, Rollo said he might give his two cents back to his father, and then they should have both alike.

Just then the boys heard some one calling,

“Rollo!”

Rollo looked up, and saw his mother at the chamber window. She was sitting there at work, and had heard their conversation.

“What, mother?” said Rollo.

“You might give him one of yours, and then you will both have twenty-two.”

They thought that this would be a fine plan, and wondered why they had not thought of it before. A few days afterwards, they decided to buy two little shovels with their money, one for each, so that they might shovel sand and gravel easier than with the wooden shovels that Jonas made.

Rollo's Garden

Farmer Cropwell

One warm morning, early in the spring, just after the snow was melted off from the ground, Rollo and his father went to take a walk. The ground by the side of the road was dry and settled, and they walked along very pleasantly; and at length they came to a fine-looking farm. The house was not very large, but there were great sheds and barns, and spacious yards, and high wood-piles, and flocks of geese, and hens and turkeys, and cattle and sheep, sunning themselves around the barns.

Rollo and his father walked into the yard, and went up to the end door, a large pig running away with a grunt when they came up. The door was open, and Rollo's father knocked at it with the head of his cane. A pleasant-looking young woman came to the door.

“Is Farmer Cropwell at home?” said Rollo's father.

“Yes, sir,” said she, “he is out in the long barn, I believe.”

“Shall I go there and look for him?” said he.

“If you please, sir.”

So Rollo's father walked along to the barn.

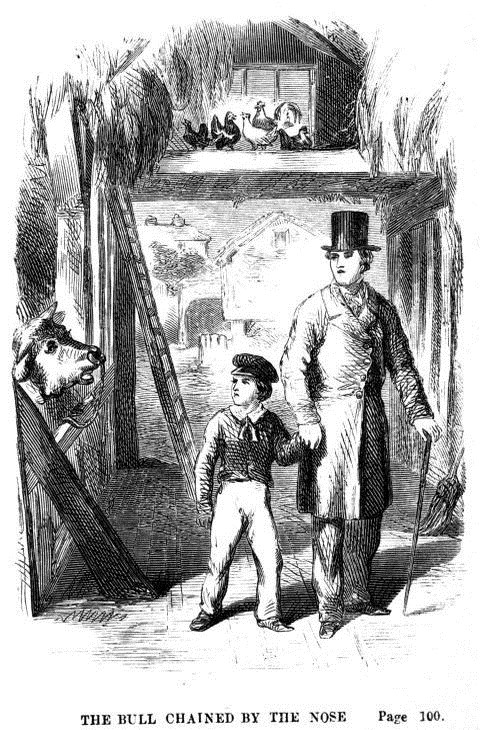

It was a long barn indeed. Rollo thought he had never seen so large a building. On each side was a long range of stalls for cattle, facing towards the middle, and great scaffolds overhead, partly filled with hay and with bundles of straw. They walked down the barn floor, and in one place Rollo passed a large bull chained by the nose in one of the stalls. The bull uttered a sort of low growl or roar, as Rollo and his father passed, which made him a little afraid; but his attention was soon attracted to some hens, a little farther along, which were standing on the edge of the scaffolding over his head, and cackling with noise enough to fill the whole barn.

The Bull Chained by the Nose.

When they got to the other end of the barn, they found a door leading out into a shed; and there was Farmer Cropwell, with one of his men and a pretty large boy, getting out some ploughs.

“Good morning, Mr. Cropwell,” said Rollo's father; “what! are you going to ploughing?”

“Why, it is about time to overhaul the ploughs, and see that they are in order. I think we shall have an early season.”

“Yes, I find my garden is getting settled, and I came to talk with you a little about some garden seeds.”

The truth was, that Rollo's father was accustomed to come every spring, and purchase his garden seeds at this farm; and so, after a few minutes, they went into the house, taking Rollo with them, to get the seeds that were wanted, out of the seed-room.

What they called the seed-room was a large closet in the house, with shelves all around it; and Rollo waited there a little while, until the seeds were selected, put up in papers, and given to his father.

When this was all done, and they were just coming out, the farmer said, “Well, my little boy, you have been very still and patient. Should not you like some seeds too? Have you got any garden?”

“No, sir,” said Rollo; “but perhaps my father will give me some ground for one.”

“Well, I will give you a few seeds, at any rate.” So he opened a little drawer, and took out some seeds, and put them in a piece of paper, and wrote something on the outside. Then he did so again and again, until he had four little papers, which he handed to Rollo, and told him to plant them in his garden.

Rollo thanked him, and took his seeds, and they returned home.

Work and Play

On the way, Rollo thought it would be an excellent plan for him to have a garden, and he told his father so.

“I think it would be an excellent plan myself,” said his father. “But do you intend to make work or play of it?”

“Why, I must make work of it, must not I, if I have a real garden?”

“No,” said his father; “you may make play of it if you choose.”

“How?” said Rollo.

“Why, you can take a hoe, and hoe about in the ground as long as it amuses you to hoe; and then you can plant your seeds, and water and weed them just as long as you find any amusement in it. Then, if you have any thing else to play with, you can neglect your garden a long time, and let the weeds grow, and not come and pull them up until you get tired of other play, and happen to feel like working in your garden.”

“I should not think that that would be a very good plan,” said Rollo.

“Why, yes,” replied his father; “I do not know but that it is a good plan enough,—that is, for play. It is right for you to play sometimes; and I do not know why you might not play with a piece of ground, and seeds, as well as with any thing else.”

“Well, father, how should I manage my garden if I was going to make work of it?”

“O, then you would not do it for amusement, but for the useful results. You would consider what you could raise to best advantage, and then lay out your garden; not as you might happen to fancy doing it, but so as to get the most produce from it. When you come to dig it over, you would not consider how long you could find amusement in digging, but how much digging is necessary to make the ground productive; and so in all your operations.”

“Well, father, which do you think would be the best plan for me?”

“Why, I hardly know. By making play of it, you will have the greatest pleasure as you go along. But, in the other plan, you will have some good crops of vegetables, fruits, and flowers.”

“And shouldn't I have any crops if I made play of my garden?”

“Yes; I think you might, perhaps, have some flowers, and, perhaps, some beans and peas.”

Rollo hesitated for some time which plan he should adopt. He had worked enough to know that it was often very tiresome to keep on with his work when he wanted to go and play; but then he knew that after it was over, there was great satisfaction in thinking of useful employment, and in seeing what had been done.

That afternoon he went out into the garden to consider what he should do, and he found his father there, staking out some ground.

“Father,” said he, “whereabouts should you give me the ground for my garden?”

“Why, that depends,” said his father, “on the plan you determine upon. If you are going to make play of it, I must give you ground in a back corner, where the irregularity, and the weeds, will be out of sight. But if you conclude to have a real garden, and to work industriously a little while every day upon it, I should give it to you there, just beyond the pear-tree.”

Rollo looked at the two places, but he could not make up his mind. That evening he asked Jonas about it, and Jonas advised him to ask his father to let him have both. “Then,” said he, “you can work on your real garden as long as there is any necessary work to be done, and then you could go and play about the other with James or Lucy, when they are here.”

Rollo went off immediately, and asked his father. His father said there would be some difficulties about that; but he would think of it, and see if there was any way to avoid them.

The next morning, when he came in to breakfast, he had a paper in his hand, and he told Rollo he had concluded to let him have the two gardens, on certain conditions, which he had written down. He opened the paper, and read as follows:—

“Conditions on which I let Rollo have two pieces of land to cultivate; the one to be called his working-garden, and the other his playing-garden.

“1. In cultivating his working-garden, he is to take Jonas's advice, and to follow it faithfully in every respect.

“2. He is not to go and work upon his playing-garden, at any time, when there is any work that ought to be done on his working-garden.

“3. If he lets his working-garden get out of order, and I give him notice of it; then, if it is not put perfectly in order again within three days after receiving the notice, he is to forfeit the garden, and all that is growing upon it.

“4. Whatever he raises, he may sell to me, at fair prices, at the end of the season.”

Planting

Rollo accepted the conditions, and asked his father to stake out the two pieces of ground for him, as soon as he could; and his father did so that day. The piece for the working-garden was much the largest. There was a row of currant-bushes near it, and his father said he might consider all those opposite his piece of ground as included in it, and belonging to him.

So Rollo asked Jonas what he had better do first, and Jonas told him that the first thing was to dig his ground all over, pretty deep; and, as it was difficult to begin it, Jonas said he would begin it for him. So Jonas began, and dug along one side, and instructed Rollo how to throw up the spadefuls of earth out of the way, so that the next spadeful would come up easier.

Jonas, in this way, made a kind of a trench all along the side of Rollo's ground; and he told Rollo to be careful to throw every spadeful well forward, so as to keep the trench open and free, and then it would be easy for him to dig.

Jonas then left him, and told him that there was work enough for him for three or four days, to dig up his ground well.

Rollo went to work, very patiently, for the first day, and persevered an hour in digging up his ground. Then he left his work for that day; and the next morning, when the regular hour which he had allotted to work arrived, he found he had not much inclination to return to it. He accordingly asked his father whether it would not be a good plan to plant what he had already dug, before he dug any more.

“What is Jonas's advice?” said his father.

“Why, he told me I had better dig it all up first; but I thought that, if I planted part first, those things would be growing while I am digging up the rest of the ground.”

“But you must do, you know, as Jonas advises; that is the condition. Next year, perhaps, you will be old enough to act according to your own judgment; but this year you must follow guidance.”

Rollo recollected the condition, and he had nothing to say against it; but he looked dissatisfied.

“Don't you think that is reasonable, Rollo?” said his father.

“Why; I don't know,” said Rollo.

“This very case shows that it is reasonable. Here you want to plant a part before you have got the ground prepared. The real reason is because you are tired of digging; not because you are really of opinion that that would be a better plan. You have not the means of judging whether it is, or is not, now, time to begin to put in seeds.”

Rollo could not help seeing that that was his real motive; and he promised his father that he would go on, though it was tiresome. It was not the hard labor of the digging that fatigued him, for, by following Jonas's directions, he found it easy work; but it was the sameness of it. He longed for something new.

He persevered, however, and it was a valuable lesson to him; for when he had got it all done, he was so satisfied with thinking that it was fairly completed, and in thinking that now it was all ready together, and that he could form a plan for the whole at once, that he determined that forever after, when he had any unpleasant piece of work to do, he would go on patiently through it, even if it was tiresome.

With Jonas's help, Rollo planned his garden beautifully. He put double rows of peas and beans all around, so that when they should grow up, they would enclose his garden like a fence or hedge, and make it look snug and pleasant within. Then, he had a row of corn, for he thought he should like some green corn himself to roast. Then, he had one bed of beets and some hills of muskmelons, and in one corner he planted some flower seeds, so that he could have some flowers to put into his mother's glasses, for the mantel-piece.

Rollo took great interest in laying out and planting his ground, and in watching the garden when the seeds first came up; for all this was easy and pleasant work. In the intervals, he used to play on his pleasure-ground, planting and digging, and setting out, just as he pleased.

Sometimes he, and James, and Lucy, would go out in the woods with his little wheelbarrow, and dig up roots of flowers and little trees there, and bring them in, and set them out here and there. But he did not proceed regularly with this ground. He did not dig it all up first, and then form a regular plan for the whole; and the consequence was, that it soon became very irregular. He would want to make a path one day where he had set out a little tree, perhaps, a few days before; and it often happened that, when he was making a little trench to sow one kind of seeds, out came a whole parcel of others that he had put in before, and forgotten.

Then, when the seeds came up in his playing-garden, they came up here and there, irregularly; but, in his working-garden, all looked orderly and beautiful.

One evening, just before sundown, Rollo brought out his father and mother to look at his two gardens. The difference between them was very great; and Rollo, as he ran along before his father, said that he thought the working plan of making a garden was a great deal better than the playing plan.

“That depends upon what your object is.”

“How so?” said Rollo.

“Why, which do you think you have had the most amusement from, thus far?”

“Why, I have had most amusement, I suppose, in the little garden in the corner.”

“Yes,” said his father, “undoubtedly. But the other appears altogether the best now, and will produce altogether more in the end. So, if your object is useful results, you must manage systematically, regularly, and patiently; but if you only want amusement as you go along, you had better do every day just as you happen to feel inclined.”

“Well, father, which do you think is best for a boy?”

“For quite small boys, a garden for play is best. They have not patience or industry enough for any other.”

“Do you think I have patience or industry enough?”

“You have done very well, so far; but the trying time is to come.”

“Why, father?”

“Because the novelty of the beginning is over, and now you will have a good deal of hoeing and weeding to do for a month to come. I am not sure but that you will forfeit your land yet.”

“But you are to give me three days' notice, you know.”

“That is true; but we shall see.”

The Trying Time

The trying time did come, true enough; for, in June and July, Rollo found it hard to take proper care of his garden. If he had worked resolutely an hour, once or twice a week, it would have been enough; but he became interested in other plays, and, when Jonas reminded him that the weeds were growing, he would go in and hoe a few minutes, and then go away to play.