Полная версия:

Fall and Rise: The Story of 9/11

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Mitchell Zuckoff 2019

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photograph © Catherine Ursillo/Getty Images

The Impossible Dream (The Quest)

From Man of La Mancha

Lyric by Joe Darion

Music by Mitch Leigh

Copyright © 1965 Andrew Scott Music and Helena Music Corp.

Copyright Renewed

All rights for Andrew Scott Music Administered by Concord Music Publishing

International Copyright Secured

All Rights Reserved

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard LLC

Designed by Leah Carlson-Stanisic

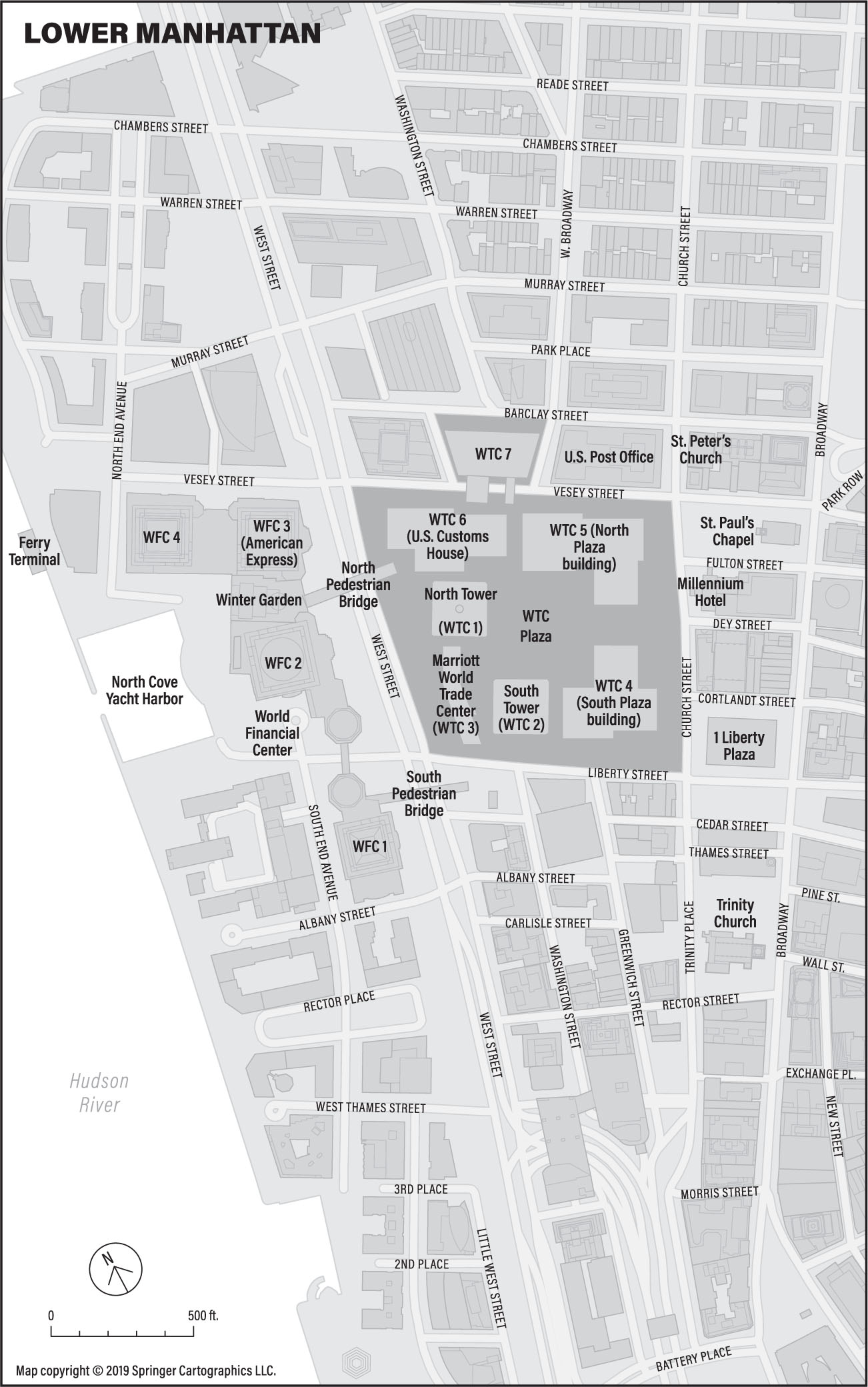

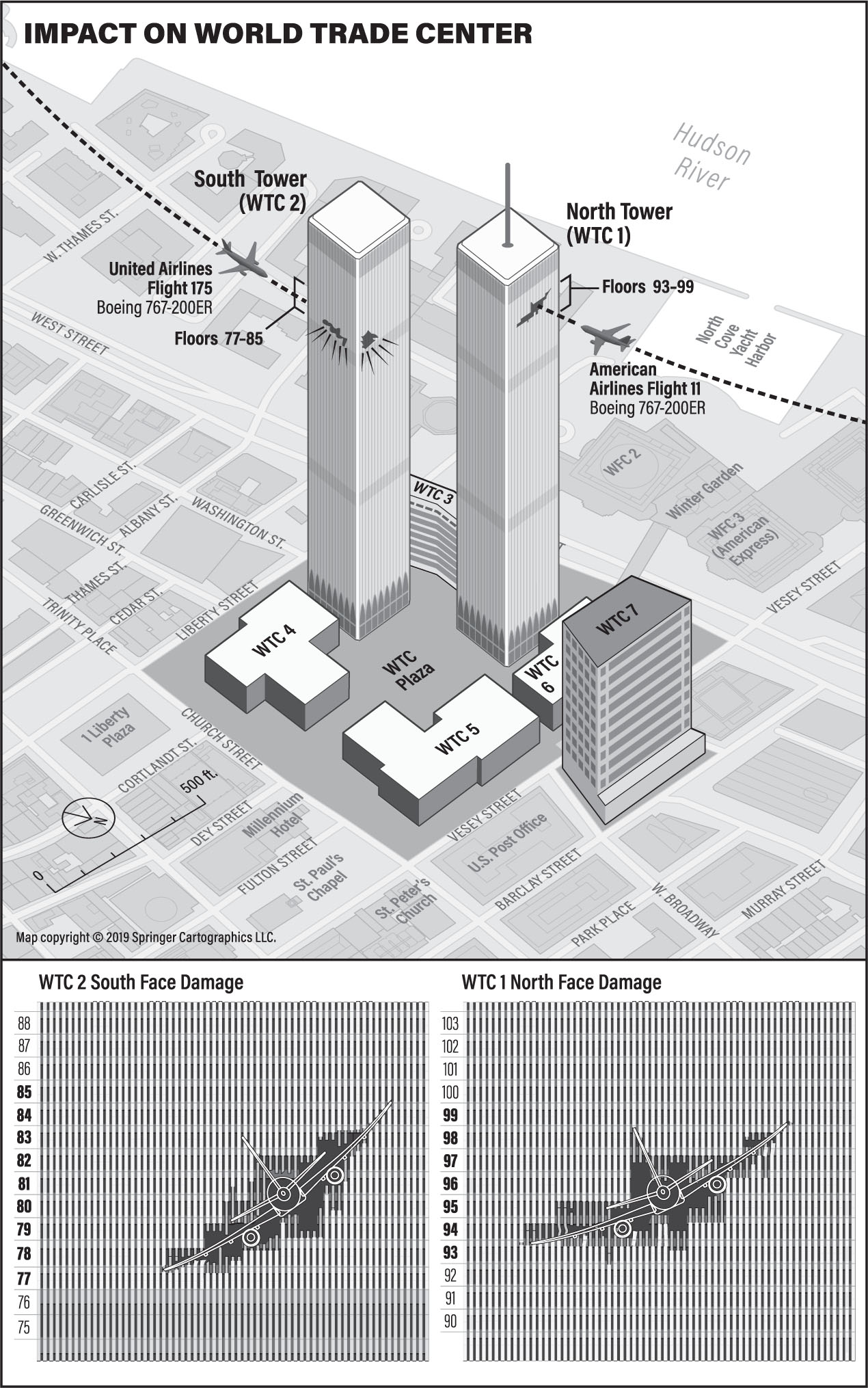

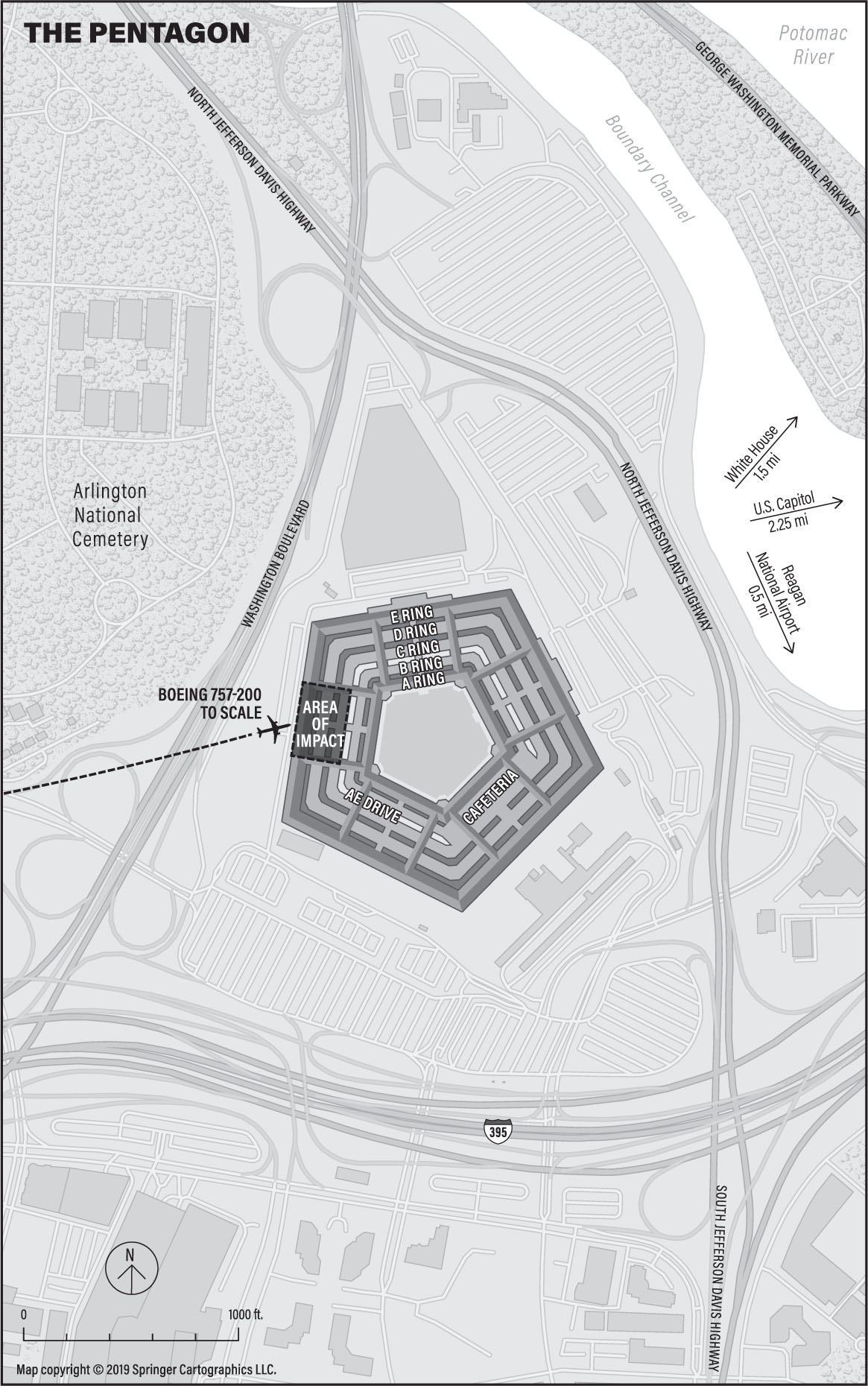

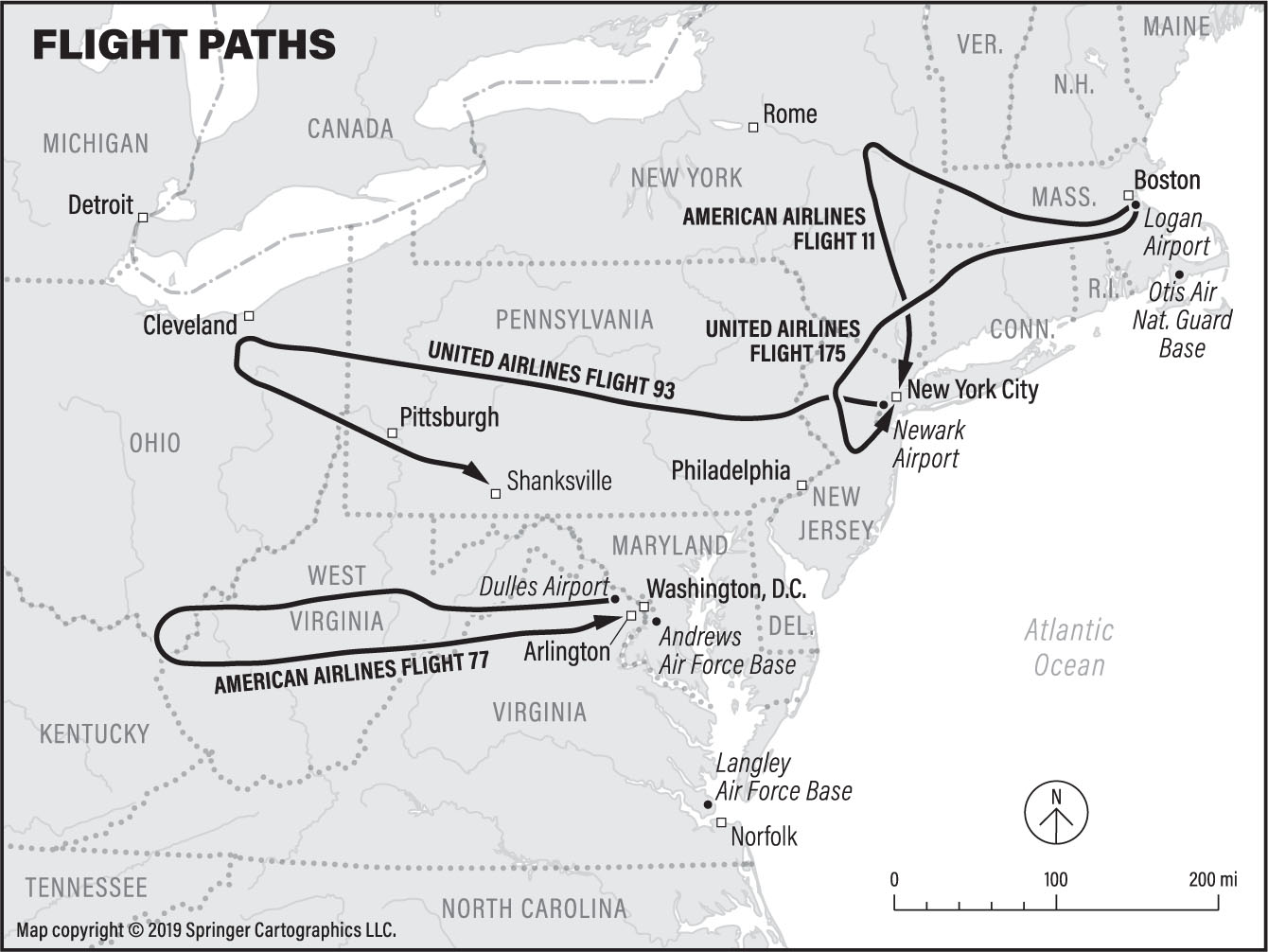

Map by Nick Springer, copyright © 2018 Springer Cartographics LLC

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Mitchell Zuckoff asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008342098

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008342128

Version 2019-04-15

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Introduction “The Darkness of Ignorance”

Prologue “A Clear Declaration of War”

PART I FALL FROM THE SKY

Chapter 1 “Quiet’s a Good Thing”

Chapter 2 “He’s NORDO”

Chapter 3 “A Beautiful Day to Fly”

Chapter 4 “I Think We’re Being Hijacked”

Chapter 5 “Don’t Worry, Dad”

Chapter 6 “The Start of World War III”

Chapter 7 “Beware Any Cockpit Intrusion”

Chapter 8 “America Is Under Attack”

Chapter 9 “Make Him Brave”

Chapter 10 “Let’s Roll”

PART II FALL TO THE GROUND

Chapter 11 “We Need You”

Chapter 12 “How Lucky Am I?”

Chapter 13 “God Save Me!”

Chapter 14 “We’ll Be Brothers for Life”

Chapter 15 “They’re Trying to Kill Us, Boys”

Chapter 16 “They Done Blowed Up the Pentagon”

Chapter 17 “I Think Those Buildings Are Going Down”

Chapter 18 “To Run, Where the Brave Dare Not Go”

Chapter 19 “Remember This Name”

Chapter 20 “This Is Your Plane Crash”

Chapter 21 “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday!”

PART III RISE FROM THE ASHES

Chapter 22 “Your Sister and Niece Will Never Be Lonely”

Appendix 1 The Fallen

Appendix 2 Timeline of Key Events on September 11, 2001

Acknowledgments

Notes

Select Bibliography

List of Searchable Terms

About the Author

Also by Mitchell Zuckoff

About the Publisher

DEDICATION

For my children—

and everyone else’s

EPIGRAPH

The ravages of many a forest fire of a bygone age may be read today in the scars left in the tree itself. The exact year that the fire occurred and some idea of its intensity are recorded in the wood, oftentimes grown over with living tissue and hid from the casual observer.

—FOREST PATHOLOGIST J. S. BOYCE, 1921

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

“The Darkness of Ignorance”

ON OCTOBER 28, 1886, PRESIDENT GROVER CLEVELAND SAILED TO A teardrop-shaped island in New York Harbor to formally accept France’s gift of the Statue of Liberty. Under leaden skies and a veil of mist, the president ended his speech with a tribute to the copper-clad lady’s torch and her symbolic power: “A stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and men’s oppression until Liberty shall enlighten the world.”

Dignitaries pounded ceremonial last rivets as warship cannons boomed. Across the water in Lower Manhattan, revelers erupted in celebration. Cobblestone streets pulsed with braying horses, throbbing drums, and blooming flower carts. Brass bands marched like front-bound soldiers, and children scrambled up lampposts to avoid being trampled.

Out-of-towners drawn to the spectacle tilted their heads to gawk at the impossibly tall buildings that loomed over them. Amused by these sky-eyed rubes, an office boy in a high tower felt seized by a raffish idea. He opened a window and tossed out long ribbons of the narrow paper tape that normally recorded the drunkard’s walk of stock prices. His pals followed suit.

“In a moment, the air was white with curling streamers,” a reporter for the New York Times observed. “Hundreds caught in the meshes of electric wires and made a snowy canopy, and others floated downward and were caught by the crowd.”

The fun was contagious. Serious men of finance became boys again, pressing against office windows to unspool paper onto the crowd. “There was seemingly no end to it,” the Times reporter wrote. “Every window appeared to be a paper mill spouting out squirming lines of tape. Such was Wall Street’s novel celebration.”

With that, the ticker-tape parade was born.

During the next one hundred fifteen years, countless tons of celebratory confetti sailed from high-rise windows onto a stretch of Lower Broadway that became known as the Canyon of Heroes. Paper blizzards honored more than two hundred explorers and presidents, war heroes and athletes, astronauts and religious figures, luminaries from Einstein to Earhart, Churchill to Kennedy, Mandela to the Mets.

Then came September 11, 2001.

Torn open, aflame, weakening from within, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center spewed paper like blood from an arterial wound. Legal documents and employee reviews. Pay stubs, birthday cards, takeout menus. Timesheets and blueprints, photographs and calendars, crayon drawings and love notes. Some in full, some in tatters, some in flames. A single scrap from the South Tower, tossed like a bottled message from a sinking ship, captured the day’s horror. In a scrawled hand, next to a bloody fingerprint, the note read:

84th floor

west office

12 People trapped

After the paper came the people. After the people came the buildings. After the buildings came the wars. The ashes cooled, but not the anguish. For years, New Yorkers couldn’t stomach a ticker-tape parade, especially so near the hallowed hole renamed Ground Zero. Yet with time, the unthinkable often becomes acceptable.

In February 2008, the underdog New York Giants won the Super Bowl. Tens of thousands of football fans gathered to celebrate, just blocks from where steel beams rose for a dazzling “Freedom Tower” at One World Trade Center, an audacious middle finger to America’s enemies, taller and bolder than the boxy twins whose sanctified footprints the new building overlooked. As the victorious Giants rolled past, their joyful supporters danced in the streets as thirty-six tons of shredded paper fluttered down upon them.

Measured in ticker tape, the return to “normal” took less than seven years.

WITH TIME, NEWS becomes history. And history, it’s been said, is what happened to other people. For anyone who lived through September 11, time might dull the anger and grief that followed the death and destruction caused when terrorists turned four commercial passenger jets into guided missiles. But the memories won’t die. The pain of the deadliest terrorist attacks in American history cut too deep, leaving knots of psychic scars that make each day an experience of before and after, of adapting to a world changed physically by every security checkpoint and psychologically by every mention of the “homeland,” a word seldom used in the United States prior to the events now known as 9/11. (The month-and-day abbreviation became the universal shorthand for the attacks largely because the digits corresponded to the nation’s 9-1-1 emergency call system; there’s no evidence the terrorists chose the date for that reason.)

Already an entire generation has no direct memory of 9/11, despite its daily effects on their lives. The historian Ian W. Toll described this progression in relation to another shocking enemy assault that also led to war: the raid on Pearl Harbor, sixty years earlier. “The passage of time strips away the searing immediacy of the surprise attack and envelops it in layers of exposition and retrospective judgment,” Toll wrote. “Hindsight furnishes us with perspective on the crisis, but it also undercuts our ability to empathize with the immediate concerns of those who suffered through it.” He quoted John H. McGoran, a sailor on the doomed battleship USS California: “If you didn’t go through it, there are no words that can adequately describe it; if you were there, then no words are necessary.”

Even if words might fail, they’re the best hope to delay the descent of 9/11 into the well of history. That is the purpose of this book. The approach is to recount the chaotic day as a narrative in three parts: events in the air, on the ground, and in the aftermath, focusing on individuals whose actions and experiences range from heroic to heartbreaking to homicidal. For every account included here, a thousand others are equally important. I’ve tried to choose stories that reveal the depth and breadth of the day without turning this into an encyclopedia. The goal is to provide a fresh perspective among readers for whom the attacks remain “news,” and to create something like memories for everyone else.

Another hope is more intimate: to attach names to some of the people directly affected by these events. Of the nearly three thousand men, women, and children killed on 9/11, arguably none can be considered a household name. The best “known” victim might be the so-called Falling Man, photographed plummeting from the North Tower of the World Trade Center. Yet even he remains nameless to most people, an anonymous icon.

THIS BOOK HAS its roots in the day itself. On September 11, 2001, as a reporter for the Boston Globe, I wrote the lead news story about the attacks, with contributions from several dozen colleagues. The work was at once historic and local: both hijacked planes that struck the Twin Towers took flight from Boston’s Logan International Airport. Five days later, with help from four reporters, I published a narrative called “Six Lives” that became the scale model for this book. It wove the stories of six people affected by, responsible for, or otherwise connected to the hijacking of American Airlines Flight 11 and the North Tower calamity. As we explained at the time, the story was designed to reveal “a nation’s shared experience, as told through their memories and the memories of their loved ones. It also creates a memorial to all those who were killed, and provides a record for all who lived.”

Several years ago, I discussed “Six Lives” at Boston University, where I teach journalism and where at least twenty-eight 9/11 victims earned degrees. Talking afterward with my friend and agent Richard Abate, we feared that many of my students, as well as several of our own children, felt little or no personal connection to 9/11. To some it seemed as distant as World War I. That realization triggered an idea: I could expand “Six Lives” to cover not only the first flight and the first tower, but all four flights and their unscheduled destinations, along with the ripples of physical and emotional effects. Time would serve not as an eraser but as an ally, yielding information and perspective collected in the years since 9/11 to deepen the account while keeping it accessible and truthful.

Speaking of truth, this book follows strict rules of narrative nonfiction. It takes no license with facts, quotes, characters, or chronologies. Descriptions of events and individuals rely on firsthand or authoritative accounts, checked for accuracy and cited in the endnotes where appropriate. All references to thoughts and emotions come from the individual in whose mind they arose, either from interviews, first-person reports, or other primary sources.

The attacks of 9/11 are among the most heavily covered events in history. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that some individuals featured in this book have had their stories told elsewhere. Several are subjects of entire books, among them Rick Rescorla, Welles Crowther, Father Mychal Judge, former FBI counterterrorism chief John O’Neill, and several heroes of United Flight 93. Some accounts included here rely on testimony from the 2006 trial of al-Qaeda member Zacarias Moussaoui, who pleaded guilty to being involved in the 9/11 plot. Overall, I mined information from government documents, law enforcement reports, trial transcripts, books, periodicals, documentaries, and broadcast and online works from reputable sources, credited where appropriate. Mainly, I relied on my own interviews with survivors, family and friends of the lost, witnesses, emergency responders, government officials, scholars, and military men and women.

Despite my efforts, and despite years of investigations, unanswered questions remain. Certain details and timeline elements are vague or in dispute. I have pointed out some of those gaps and disagreements in the text or in the notes. I have not included unfounded allegations or pseudoscience from the cottage industry of 9/11 conspiracy theorists. Facts are stubborn and powerful: this is a true story.

THE ESSENTIAL JOB of journalism, from daily reporting to narrative history, is to answer six fundamental questions: who, what, where, when, why, and how. Motivation being the great mystery of human existence, the most elusive is usually “why.” As in: “Why did terrorists who claimed to be acting on behalf of Islam hijack commercial airliners to crash them into U.S. civilian and government targets on 9/11?”

By focusing primarily on the day itself, I’ve left deep exploration of that question to others. Readers inclined toward further pursuit of “why” should seek out additional works. Three worth reading are Steve Coll’s excellent Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001; Terry McDermott’s Perfect Soldiers: The 9/11 Hijackers: Who They Were, Why They Did It; and Lawrence Wright’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11.

Wright traced the forces, philosophers, and practitioners of the 9/11 brand of jihad, an Arabic word that translates as “struggle.” His accomplishment cannot be reduced to a few lines, but he masterfully examined the mindset of those responsible for the attacks:

Christianity—especially the evangelizing American variety—and Islam were obviously competitive faiths. Viewed through the eyes of men who were spiritually anchored in the seventh century, Christianity was not just a rival, it was the archenemy. To them the Crusades were a continual historical process that would never be resolved until the final victory of Islam.

Wright also provided insight into the men who carried out the hijackings:

Radicalism usually prospers in the gap between rising expectations and declining opportunities… . Anger, resentment, and humiliation spurred young Arabs to search for dramatic remedies. Martyrdom promised such young men an ideal alternative to a life that was so sparing in its rewards. A glorious death beckoned to the sinner, who would be forgiven, it is said, with the first spurt of blood, and he would behold his place in Paradise even before his death.

Of the other exceptional books about 9/11, including those cited in the Select Bibliography, several deserve acknowledgment: The Ground Truth: The Untold Story of America Under Attack on 9/11 by John Farmer, senior counsel to the 9/11 Commission, distills how government and military officials served (and misled) the public; The Eleventh Day: The Full Story of 9/11, by Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan, is an impressive synthesis of information about these events; and 102 Minutes, by Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn of the New York Times, lives up to its subtitle: The Unforgettable Story of the Fight to Survive inside the Twin Towers. The 9/11 Commission’s final report is an essential resource, as are the commission’s voluminous staff statements, hearing transcripts, and monographs. I benefited greatly from the work of former 9/11 Commission investigator Miles Kara, who maintains the insightful website “9-11 Revisited,” at www.oredigger61.org.

In the pages ahead, my goal is to fulfill the promise I made in 2001 with “Six Lives”: to create a memorial to all those who were killed and to provide a record for all who survived. Plus one more: to build understanding among those who follow.

—Mitchell Zuckoff, Boston

PROLOGUE

“A Clear Declaration of War”

THIS BOOK COULD BEGIN NEARLY FOUR DECADES BEFORE 9/11, IN 1966, with Egypt’s execution of a fanatically anti-Western author named Sayyid Qutb, whose writings inspired two generations of Islamist terror groups. Or further back in time, to 1918, with the defeat of the last great Muslim empire, the Ottoman sultanate. Or even further, to 1798, the year Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Egypt. Or seven hundred years before that, with the start of the Crusades. Or five hundred years before that, when Muslims believe the first verses of the Quran were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Or more than two thousand years earlier, with the birth of Abraham.

When it comes to historical storytelling, it’s impossible for one volume to capture everything that came before. Yet a story must start somewhere. In this case, consider a relatively recent date: February 23, 1998. On that day, a shadowy forty-year-old Islamic militant named Osama bin Laden issued a fatwa, a furious religious decree. His edict declared war on the United States and all its citizens, wherever they or their interests could be found.

Faxed to an Arabic newspaper in London, the fatwa was signed by bin Laden, a Saudi heir to a construction fortune who was living in Afghanistan, and three other belligerent Islamic leaders, from Egypt, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Their declaration invoked a militant interpretation of jihad that they said obligated every Muslim to violently defend holy lands against enemies. Two years earlier, bin Laden had issued a narrower fatwa, aimed at military targets, that called for the removal of American troops from Saudi Arabia: “[E]xpel the enemy, humiliated and defeated, out of the sanctities of Islam.” The new fatwa went much further.

In florid language, the February 1998 fatwa asserted that three primary offenses justified a declaration of global war: (1) the presence of American military forces on the holiest lands of Islam, the Arabian Peninsula; (2) the U.S.-led war in Iraq; and (3) the United States’ support of Israel, in particular its control of Jerusalem. “All of these crimes and sins committed by the Americans,” the statement said, “are a clear declaration of war on Allah, his messenger, and Muslims.” In response, bin Laden and his cohort issued a command: “The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it… . We—with Allah’s help—call on every Muslim who believes in Allah and wishes to be rewarded to comply with Allah’s order to kill the Americans and plunder their money wherever and whenever they find it.”

By the time he released his more strident fatwa, the bearded, lanky bin Laden was no stranger to American intelligence agencies. Between 1996 and 1997, U.S. officials learned that he headed his own terrorist group and was involved in a 1992 attack on a hotel in Yemen that housed U.S. military personnel. They also discovered that bin Laden had played a role in the “Black Hawk Down” shootdown of U.S. Army helicopters in Somalia in 1993 and had possibly orchestrated a 1995 car bombing in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, that killed five Americans working with the Saudi National Guard. After the fatwa, bin Laden’s threat profile rose dramatically among U.S. officials, especially when, six months later, sources blamed him for the nearly simultaneous bombings of American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, in neighboring Tanzania, which killed more than two hundred people. In response to those bombings, President Bill Clinton authorized an attack using Tomahawk missiles aimed at six sites in Afghanistan. American officials believed that bin Laden would be at one of the target locations, but he had left hours earlier, apparently tipped off by Pakistani officials.

Bin Laden remained a focus of kill or capture discussions, even as a federal grand jury in New York indicted him in absentia in 1998 for conspiracy to attack U.S. defense installations. The U.S. intelligence community formally described his terror group, called al-Qaeda, or “the Base,” in 1999, fully eleven years after its formation. The attention only emboldened him. Bin Laden struck again in October 2000, when a small boat loaded with explosives tore a hole in a U.S. Navy destroyer, the USS Cole, as it refueled off the coast of Yemen. The blast killed seventeen crew members and injured dozens more.

Yet even as they tried to keep tabs on bin Laden, even as warning signals became sirens, American political and intelligence leaders never fully grasped how determined he was to execute his fatwa with mass murder inside the United States. Despite solid clues—which intensified during the summer of 2001—and sincere investigative efforts by a small number of individuals, overall the U.S. government response to bin Laden was characterized by missed connections, squandered opportunities, and overlooked signs of impending disaster. An intelligence-gathering structure built to monitor Russian men with bad suits and nuclear warheads didn’t know what to make of a fanatical Saudi in flowing robes issuing fatwas by fax machine.

Even discounting for hindsight, overwhelming evidence shows that the U.S. government’s failure to anticipate the attacks of 9/11 was as widespread as it was ultimately devastating. Scores of examples prove that point, but consider one. Several months before 9/11, the head of analysis for the U.S. government’s Counterterrorism Center wrote: “It would be a mistake to redefine counterterrorism as a task of dealing with ‘catastrophic,’ ‘grand,’ or ‘super’ terrorism, when in fact most of these labels do not represent most of the terrorism that the United States is likely to face or most of the costs that terrorism imposes on U.S. interests.” Those very labels—“catastrophic,” “grand,” “super-terrorism”—were in fact the perfect descriptions of what was about to happen.