Полная версия:

Black Jade

Black Jade

Book Three of the Ea Cycle

DAVID ZINDELL

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely fictional.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2005

Copyright © David Zindell 2005

David Zindell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006486220

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2016 ISBN 9780007387717

Version: 2016-09-01

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

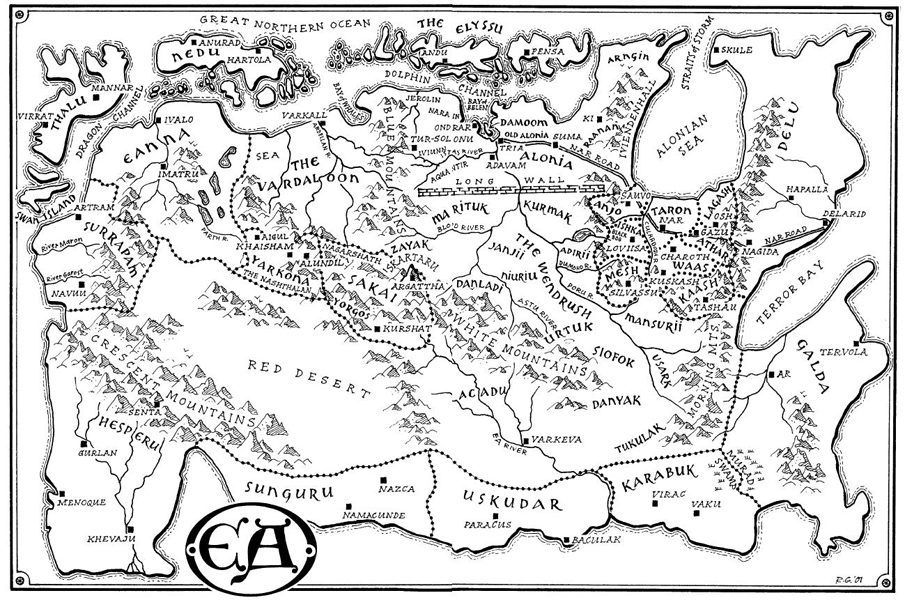

Map

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Keep Reading

Appendices

Heraldry

The Gelstei

The Greater Gelstei

The Lesser Gelstei

Books of the Saganom Elu

The Ages of Ea

The Months of the Year

About the Author

By David Zindell

About the Publisher

Map

1

Each man and woman is a star. As long as we are alive, my grandfather used to say, we must endure burning if we are to give light. As for the dead, only the dead know if their eternal flame is a glory or an anguish. In the heavens they shine through the dark nights of the ages in uncountable numbers. There, since I was a child, my grandfather has dwelled with Aras and Solaru and the other brightest lights. There, my mother and father, my grandmother and brothers, have joined him, sent on by the deadly lies and misdeeds of one they loved. Some day, it is said, a man will come forth and impel the stars to end their vast silence, and then these splendid orbs will sing their long, deep, fiery songs to those who listen. Will this Shining One, with the Lightstone in his hands, cool the tormented hearts of men, the living and the dead? I must believe that he will. For it is also said that the Lightstone gathers all things to itself. Within its luminous center dwells the earth and men and women and all the stars – and the blackness between them that allows them to be seen.

The Lightstone, however, was as far from this Shining One’s grasp as the sun was from mine. With the Red Dragon’s ravaging of my father’s castle to steal the golden cup, men and women in every land were looking toward the Dragon’s stronghold of Argattha with fevered and fearful eyes. In Surrapam, the victorious armies of King Arsu stood ready to conquer Eanna and the other Free Kingdoms of the far west, and crucify their peoples in the Dragon’s name. In Alonia, mightiest of realms, quarrelsome dukes and lords slew each other to gain King Kiritan’s vacant throne. Across the Morning Mountains of my home, the Valari kings fought as always for ancient grudge and glory. A great rebellion in Galda had ended with ten thousand men being mounted on crosses of wood. The Wendrush was a sea of grass running red with the blood of the Sarni tribes. Too many of these fierce warriors had surrendered their independence to declare for the Red Dragon, whose name was Morjin. As scryers had foreseen in terrible visions, it seemed that the whole world was about to burn up in a holocaust that would blacken the very stars.

And yet, as the scryers had also told, somewhere on Ea lived the Shining One: the last Maitreya who might bring a light so pure and sweet that it would put out this all-consuming fire. I sought this great-souled being. My friends – heroes, all, of the Quest to find the Lightstone – sought him, too. Our new quest, by day and by night, took us ever farther from the green valleys and snow-capped mountains of my homeland. To the west we journeyed, following the fiery arc of Aras and Varshara and the other bright stars of the ancient constellations where they disappeared beyond the dark edge of the heavens.

And others followed us. Early in Ashte in the year 2814 of the Age of the Dragon, a squadron of Morjin’s famed Dragon Guard and their Sarni allies pursued us across the Wendrush’s rolling steppe. Our enemies seemed not to care that we were under the escort of forty-four Sarni warriors of the Danladi tribe; for three days, as we approached the great, icy, stone wall of the White Mountains, they had ridden after us like shadows through the Danladi’s country – always keeping at a distance that neither threatened nor invited attack. And for three nights, they had built their campfires and cooked their dinners scarcely a mile from the sites that we chose to lay our sleeping furs. When the third night fell upon the world and the wind shifted and blew at us from the north, we could smell the smoky char of roasting meat and other more disturbing scents.

On a swell of dark grass at the edge of our camp, I stood with my friend Kane gazing out to the northwest at the orange glow of our enemy’s campfires. Kane’s cropped, white hair was a silvery sheen beneath a round, silver moon. He stared off into the starlit distances, and his lips pulled back from his white teeth in a fearsome grimace. His large, savage body trembled with a barely-contained fury. I could almost hear him howling out his hate, like a great, white wolf of the steppe lusting to rend and slay.

‘So, Val, so,’ he said to me. ‘We must decide what we are to do about these crucifiers, and soon.’

He turned his gaze upon me then. As always, I saw too much of myself in this vengeful man, and of him in me. His bright, black eyes were like a mirror of my own. He was nearly as tall as I; his nose was that of a great eagle, and beneath his weathered, ivory skin, the bones of his face stood out boldly. Between us was a likeness that others had remarked: of form, certainly, for he looked as much a Valari warrior as had my father and brothers. But our deeper kinship, I thought, was not of the blood but the spirit. Now that my family had all been slaughtered, I sometimes found the best part of them living on in his aspect: strange, wild, beautiful and free.

I smiled at him and then turned back toward our enemy’s campfires. One of our Sarni escort, after earlier riding close enough to take an arrow through the arm, had put their numbers at fifty: twenty-five Zayak warriors under some unknown chief or headman and as many of the Red Knights, with their dragon blazons and their iron armor, tinctured red as with blood.

‘We might yet outride them,’ I said to Kane. ‘Perhaps tomorrow, we should put it to the test.’

We could not, of course, so easily escape the Zayak warriors, for none but a Sarni could outride a Sarni. The Red Knights, however, encased in heavy armor and mounted on heavy horses, moved more slowly. Of our company, only Kane and I, with our friend, Maram, wore any kind of real armor: supple mail forged of Godhran steel that was lighter and stronger than anything Morjin’s blacksmiths could hammer together. Our horses, I thought, were better, too: Fire, Patience and Hell Witch, and especially my great, black warhorse, Altaru, who stood off a hundred paces with our other mounts taking his fill of the steppe’s new, sweet grass.

‘Well, then,’ Kane said to me, ‘we must test it before we reach the mountains.’

He pointed off toward the great, snow-capped peaks that glinted beneath the western stars. As he held out his thick finger, his mail likewise glinted from beneath his gray, wool traveling cloak, similar in cut and weave to my own.

‘So, then – fight or flee,’ he growled out. ‘And I hate to flee.’

As we pondered our course, mostly in silence, a great bear of a man stood up from the nearby campfire and ambled over to hear what we were discussing. He tried to skirt the inevitable piles of horse or sagosk dung, and other imagined dangers of the dark grass, all the while sipping from a mug of sloshing brandy. I drank in the form of my best friend, Maram Marshayk. Once a prince of Delu and an honorary Valari knight of great renown, fate had reduced him to accompanying me into Ea’s wild lands as outcasts.

‘Ah, I heard Kane say something about fleeing,’ he said to us. A belch rumbled up from his great belly, and he wiped his lips with the back of his hand. ‘My father used to say that whoever runs away lives to fight again another day.’

His soft eyes found mine through the thin light as his thick, sensuous lips broke into a smile. Upon taking in the whole of his form – the dense, curly beard which covered his heavy face, no less his massive chest, arms and legs – I decided that it would be a bad idea to try to outride the Red Knights. No weight of their armor, be it made of steel plate, could match the mass of muscle and fat that padded the frame of Maram Marshayk.

‘If we flee,’ Kane said to him, poking his finger into Maram’s belly, ‘are you willing to be left behind when your horse dies of exhaustion?’

It was too dark to see Maram’s florid face blanch, but I felt the blood drain from it, even so. He looked out toward our enemy’s campfires, and said, ‘Would you really leave me behind?’

‘So, I would,’ Kane growled out. His dark eyes drilled into Maram. ‘At need, I’d sacrifice any and all of us to fulfill this quest.’

Maram took a long pull of brandy as he turned to regard Kane. ‘Ah, a sacrifice is it, then? Well, I won’t have that on your conscience. If a sacrifice truly needs to be made, I’ll turn to cross lances with the Red Knights by myself.’

I looked back and forth between Maram and Kane as they glared at each other. I did not think that either of them was quite telling the truth. I rested my hand on Maram’s shoulder as I caught Kane’s gaze. And I said, ‘No one is going to be left behind. And we will fulfill this quest, as we did the first.’

Just then Master Juwain, sitting with our other friends by the fire, finished writing something in one of his journals and came over to us. He was as small as Maram was large and as ugly as Kane was well-made. His head somewhat resembled a walnut, and a misshapen one at that: all lumpy and bald with a knurled nose and ears that stuck out too far. But I had never known a man whose eyes were so intelligent and clear. Like the rest of us, he wore a gray traveling cloak, though he refused to bind his limbs in steel rings or carry any weapon more deadly than the little knife he used to sharpen his quills.

‘Come,’ he said as he grasped Maram’s wrist. ‘If we’re to hold council, let us all sit together. Liljana is nearly finished making dinner.’

I looked over toward the fire where a plump, matronly woman bent over a pot of bubbling stew. A girl about ten years old sat next to her making cakes on a griddle while a boy slightly older poked the fire with a long, charred stick.

‘Excellent,’ Maram agreed, ‘we’ll eat and then we’ll talk.’

‘You would talk more cogently,’ Master Juwain told him, ‘if you would take your drink after you eat. Or forbear it altogether.’

With fierce determination, Master Juwain suddenly clamped his knotted fingers around Maram’s mug. His small hands were surprisingly strong, from a lifetime of disciplines and hard work, and he managed to pry free the mug from Maram’s thick palm.

Maram eyed the mug as might a child a candy that has been taken from him. He said, ‘I have forborne my brandy these last three days, waiting for the Red Knights to attack us, too bad. As for talk, cogent as it is clever, please don’t forget that I’m now called Five-Horned Maram.’

Once, a lifetime ago it seemed, Maram had been an adept of the Great White Brotherhood under the tutelage of Master Juwain, and everyone had called him ‘Brother Maram.’ But he had long since abjured his vows to forsake wine, women and war. Now he wore steel armor beneath his cloak and bore a sword that was nearly as long and keen as my own. Less than a year before, in the tent of Sajagax, the Sarni’s mightiest chieftain, he had become the only man in memory to down five great horns of the Sarni’s potent beer – and to remain standing to tell everyone of his great feat.

Kane continued glaring at Maram, and again he poked his steely finger into his belly. He said, ‘You’d do well to forbear brandy and bread, at least for a while. Are you trying to kill yourself, as well as your horse?’

In truth, ever since the Battle of Culhadosh Commons and the sack of my father’s castle, Maram had been eating enough for two men and drinking more than enough for five.

‘Forbear, you say?’ he muttered to Kane. ‘I might as well forbear life itself.’

‘But you’re growing as fat as a bear.’

Maram patted his belly and smiled. ‘Well, what if I am? Haven’t you seen a bear eat when winter is coming?’

‘But it’s Ashte – in another month, summer will be upon us!’

‘No, my friend, there you’re wrong,’ Maram told him, with a shake of his head and another belch. ‘Wherever we journey, it will be winter – and deep winter at that, for we’ll be deep into this damn new quest. Do you remember the last time we went tramping all across Ea? I nearly starved to death. And so is it not the soul of prudence that I should fortify myself against the deprivations that are sure to come?’

Kane had no answer against this logic. And so he snapped at Maram: ‘Fortify yourself then, if you will. But at least forbear your brandy until there’s a better time and place to drink it.’

So saying, he took the mug from Master Juwain and moved to empty its contents onto the grass.

‘Hold!’ Maram cried out. ‘It would be a crime to waste such good brandy!’

‘So,’ Kane said, eyeing the dark liquor inside the mug. ‘So.’

He smiled his savage smile, as if the great mystery of life’s unfairness pleased him almost as much as it pained him. Then, with a single, quick motion, he put the mug to his lips and threw down the brandy in three huge gulps.

‘Forbear yourself, damn you!’ Maram called out to him.

‘Damn me? You should thank me, eh?’

‘Thank you why? For saving me from drunkenness?’

‘No – for taking a little pleasure from this fine brandy of yours.’

Kane handed the mug back to Maram, who stood looking into its hollows.

‘Ah, well, I suppose one of us should have savored it,’ he said to Kane. ‘It pleases me that it pleased you so deeply, my friend. Perhaps someday I can return the favor – and save you from becoming a drunk.’

Kane smiled at this as Maram began laughing at the little joke he had made, and so did Master Juwain and I. One mug of brandy had as much effect on the quenchless Kane as a like amount of water would on all the sea of grasses of the Wendrush.

I looked at Kane as I tapped my finger against Maram’s cup. I said, ‘Perhaps we should all forbear brandy for a while.’

‘Ha!’ Kane said. ‘There’s no need that I should.’

‘The need is to encourage Maram to remain sober,’ I said. I couldn’t help smiling as I added, ‘Besides, we all must make sacrifices.’

Kane looked at Maram for an uncomfortably long moment, and then announced, ‘All right then, if Maram will vow to forbear, so shall I.’

‘And so shall I,’ I said.

Maram blinked at the new moisture in his eyes; I couldn’t quite tell if our little sacrifice had moved him or if the prospect of giving up his beloved brandy made him weep. And then he clapped me on the arm as he nodded at Kane and said, ‘You would do that for me?’

‘We would,’ Kane and I said with one breath.

‘Ah, well, that pleases me more than I could ever tell you, even if I had a whole barrel full of brandy to loosen my tongue.’ Maram paused to dip his fat finger down into the mug, moistening it with the last few drops of brandy that clung to its insides. Then he licked his finger and smiled. ‘But I must say that I would wish no such deprivation upon my friends. Just because I suffer doesn’t mean that the rest of the world must, too.’

I glanced at the campfires of our enemies, then I turned back to look at Maram. ‘In these circumstances, we’ll gladly suffer with you.’

‘Very well,’ Maram said. Then he nodded at Master Juwain. ‘Sir, will you be a witness to our vows?’

‘Even as I was once before,’ Master Juwain said dryly.

‘Excellent,’ Maram said. ‘Then unless it be needed for, ah, medicinal purposes, I vow to forbear brandy until we find the one we seek.’

‘Ha!’ Kane cried out. ‘Rather let us say that unless Master Juwain prescribes brandy for medicinal purposes, we shall all forbear it.’

‘Excellent, excellent,’ Maram agreed, nodding his head. He held up his mug and smiled. ‘Then why don’t we all return to the fire and drink one last toast to our resolve?’

‘Maram!’ I half-shouted at him.

‘All right, all right!’ he called back. The breath huffed out of him, and for a moment he seemed like a bellows emptied of air. ‘I was just, ah, testing your resolve, my friend. Now, why don’t we all go have a taste of Liljana’s fine stew. That, at least, is still permitted, isn’t it?’

We all walked back to the fire and sat down on our sleeping furs set out around it. I smiled at Daj, the dark-souled little boy that we had rescued out of Argattha along with the Lightstone. He smiled back, and I noticed that he was not quite so desperate inside nor small outside as when we had found him a starving slave in Morjin’s hellhole of a city. It was a good thing, smiling, I thought. It lifted up the spirit and gave courage to others. I silently thanked Maram for making me laugh, and I resolved to sustain my gladness of life as long as I could. This was the vow I had made, high on a sacred mountain above the castle where my mother and grandmother had been crucified.

Daj, sitting next to me, jabbed the glowing end of his firestick toward me and called out, ‘At ready! Let’s practice swords until it’s time to eat!’

He moved to put down his stick and draw the small sword I had given him when we had set out on our new quest. His enthusiasm for this weapon both impressed and saddened me. I would rather have seen him playing chess or the flute, or even playing at swords with other boys his age. But this savage boy, I reminded myself, had never really been a boy. I remembered how in Argattha he had fought a dragon by my side and had stuck a spear into the bodies of our wounded enemies.

‘It is nearly time to eat,’ Liljana called out to us. Her heavy breasts moved against her thick, strong body as she stirred the succulent-smelling stew. ‘Why don’t you practice after dinner?’

Although her words came out of her firm mouth as a question, sweetly posed, there was no question that we must put off our swordwork until later. Beneath her bound, iron-gray hair, her pleasant face betrayed an iron will. She liked to bring the cheer and good order of a home into our encampments by directing cooking, eating and cleaning, even talking, and many other details of our lives. I might be the leader of our company on our quest across Ea’s burning steppes and icy mountains, but she sought by her nature to try to lead me from within. Through countless kindnesses and her relentless devotion, she had dug up the secrets of my soul. It seemed that there was no sacrifice that she wouldn’t make for me – even as she never tired, in her words and deeds, of letting me know how much she loved me. At her best, however, she called me to my best, as warrior, dreamer and man. Now that the insides of my father’s castle had been burnt to ashes, she was the only mother I still had.

‘There will be no swordwork tonight,’ I said, to Liljana and Daj, ‘unless the Red Knights attack us. We need to hold council.’

‘Very well, then, but I hope you’re not still considering attacking them.’ Liljana looked through the steam wafting up from the stew, straight at Kane. She shook her head, then called out, ‘Estrella, are those cakes ready yet?’

Estrella, a dark, slender girl of quicksilver expressions and bright smiles, clapped her hands to indicate that the yellow rushk cakes – piled high on a grass mat by her griddle – were indeed ready to eat. She could not speak, for she, too, had been Morjin’s slave, and he had used his black arts to steal the words from her tongue. But she had the hearing of a cat; in truth, there was something feline about her, in her wild, triangular face and in the way she moved, instinctually and gracefully, as if all the features of the world must be sensed and savored. With her black curls gathered about her neck, her lustrous skin and especially her large, luminous eyes, she possessed a primeval beauty. I had never known anyone, not even Kane, who seemed so alive.

Almost without thought, she plucked one of the freshest cakes from the top of the piles and placed it in my hand. It was still quite hot, though not enough to burn me. As I took a bite out of it, her smile was like the rising sun.

‘Estrella, you shouldn’t serve until we’re all seated,’ Liljana instructed her.

Estrella smiled at Liljana, too, though she did not move to do as she was told. Instead, seeing that I had finished my cake, she gave me another one. She delighted in bringing me such little joys as the eating of a hot, nutty rushk cake. It had always been that way between us, ever since I had found her clinging to a cold, castle wall and saved her from falling to her death. And countless times since that dark night, in her lovely eyes and her deep covenant with life, she had kept me from falling into much worse.