Полная версия:

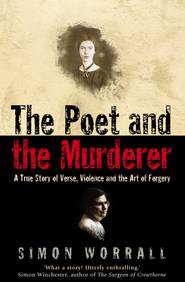

The Poet and the Murderer: A True Story of Verse, Violence and the Art of Forgery

The Poet AND THE Murderer

A True Story of Verse, Violence

and the Art of Forgery

SIMON WORRALL

Dedication

To my parents, Nancy and Philip; and to my beloved wife, Kate

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue: The Poet and the Murderer

Chapter 1 Emily Dickinson for Sale

Chapter 2 A Riddle in a Locked Box

Chapter 3 A Search for Truth

Chapter 4 Auction Artifice

Chapter 5 In the Land of Urim and Thummim

Chapter 6 The Forger and His Mark

Chapter 7 The Magic Man

Chapter 8 The Art of Forgery

Chapter 9 The Salamander Letter

Chapter 10 Isochrony

Chapter 11 The Myth of Amherst

Chapter 12 The Oath of a Freeman

Chapter 13 A Dirty, Nasty, Filthy Affair

Chapter 14 The Kill Radius

Chapter 15 Cracked Ink

Chapter 16 Victims

Chapter 17 A Spider in an Ocean of Air

Epilogue: Homestead

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘The Heart wants what it wants – or else it does not care–’

Emily Dickinson

‘We have the greatest and smoothest liars in the world, the cunningest and most adroit thieves, and any other shade of character that you can mention…. I can produce Elders here who can shave their smartest shavers, and take their money from them. We can beat the world at any game.’

Brigham Young

Introduction

It was a cold, crisp fall day as I walked up the driveway of the Emily Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts. A row of hemlock trees along the front of the house cast deep shadows on the brickwork. A squirrel scampered across the lawn with an acorn between its teeth. Entering by the back door, I walked along a dark hallway hung with family portraits, then climbed the stairs to the second-floor bedroom.

The word Homestead is misleading. With its elegant cupola, French doors, and Italian facade, this Federal-style mansion on Main Street, which the poet’s grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, built in 1813, is anything but a log cabin. Set back from the road, with a grove of oaks and maples screening it to the rear, and a large, concealed garden, it was, and is, one of the finest houses in Amherst.

The bedroom was a large, square, light-filled room on the southwest corner. One window looked down onto Main Street. From the other window I could see the Evergreens, where Emily Dickinson’s brother, Austin, and her sister-in-law, Sue Gilbert Dickinson, had lived. Halfway along the east wall was the sleigh bed where the poet had slept, always alone, for almost her entire life. She was less than five and a half feet tall, and the bed was as small as a child’s. I prodded the mattress. It felt hard and unyielding. In front of the window looking across to the Evergreens was a small writing table. It was here that Dickinson wrote almost all of her poetry, and the nearly one thousand letters that have come down to us. Poems came to this high-spirited, fiercely independent redhead in bursts of language, like machine-gun fire. She scribbled down drafts of poems, mostly in pencil, on anything she had to hand as she went about her daily chores: the backs of envelopes, scraps of kitchen or wrapping paper. Once she used the back of a yellow chocolate-box wrapper from Paris. She wrote a poem on the back of an invitation to a candy pulling she had received a quarter of a century earlier. The painstaking work of revision and editing was done mostly at night at this table. Working by the light of an oil lamp, she copied, revised, and edited, often over a period of several years, the half-formed thoughts and feelings she had jotted down while baking gingerbread, walking her invalid mother in the garden, or tending the plants in the conservatory her father had built for her, and which was her favorite place in the Homestead.

I stood by the table imagining her working there, with her back to me, her thick hair piled on top of her head, the lines of her body visible under her white cotton dress. Then I hurried back down the stairs, crossed the parking lot to where I had left my car, and drove the three quarters of a mile to the Jones Library on Amity Street. There was a slew of messages on my cell phone. One was from a gun dealer in Salt Lake City. Another was from the head of public relations at Sotheby’s in New York. A third was from an Emily Dickinson scholar at Yale University named Ralph Franklin. I did not know it at the time, but these calls were strands in a web of intrigue and mystery that I would spend the next three years trying to untangle. It had all begun when I came across an article in The New York Times, in April 1997, announcing that an unpublished Emily Dickinson poem, the first to be discovered in forty years, was to be auctioned at Sotheby’s. I did not know much about Dickinson at the time, except that she had lived an extremely reclusive life and that she had published almost nothing during her lifetime. The idea that a new work by a great artist, whether it is Emily Dickinson or Vincent van Gogh, could drop out of the sky like this, appealed to my sense of serendipity. Who knows, I remember thinking, maybe one day they will find the original manuscript of Hamlet.

I thought nothing more about the matter until four months later, at the end of August, when I came across a brief four-line announcement at the back of the ‘Public Lives’ section of The New York Times. It reported that the Emily Dickinson poem recently purchased at auction at Sotheby’s for $21,000, by the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts, had been returned as a forgery.

What sort of person, I wondered, had the skill and inventiveness to create such a thing? Getting the right sort of paper and ink would be easy enough. But to forge someone else’s handwriting so convincingly that it could get past Sotheby’s experts? That, I guessed, would be extremely hard. This forger had gone even farther. He had written a poem good enough for it to be mistaken for a genuine work by one of the world’s most original and stylistically idiosyncratic artists. Somehow he had managed to clone Emily Dickinson’s art.

I was also curious about the poem’s provenance. Where had it come from? Whose hands had it passed through? What had Sotheby’s known when they agreed to auction it? The illustrious British firm of auctioneers was much in the news. There were stories of chandelier bids and gangs of professional art smugglers in Italy and India. Had Sotheby’s investigated the poem’s provenance? Or had they known all along that the poem might be a forgery, but had proceeded with the auction in the hope that no one would be able to prove it was?

To find out the answers to some of these questions I called Daniel Lombardo, the man who had bought the poem for the Jones Library in Amherst. What he told me only heightened my curiosity. A few days later I packed a bag and headed north from my home in Long Island toward Amherst with a copy of Emily Dickinson’s poems on the seat beside me.

It was the beginning of a journey that would take me from the white clapboard villages of New England to the salt flats of Utah; from the streets of New York to the Las Vegas Strip. At the heart of that journey were a poet and a murderer. Finding out how they were linked, how one of the world’s most audacious forgeries had been created and how it had got from Utah to Madison Avenue, became an all-consuming obsession. In my search for the truth I would travel thousands of miles and interview dozens of people. Some, like Mark Hofmann’s wife, spoke to me for the first time on record. But I quickly discovered the ‘truth,’ where Mark Hofmann is concerned, is a relative concept. Whether it was his friends and family, or the dealers and auction houses who traded in his forgeries, all claimed to be the innocent victims of a master manipulator. Who was telling the truth? Was anyone? It was like pursuing someone through a labyrinth of mirrors. Paths that promised to lead out of the maze would turn into dead ends. Others that appeared to lead nowhere would suddenly open, leading me forward in directions I had not anticipated. Nothing was what it seemed.

Ahead of me, but always just out of reach, was the forger himself. William Hazlitt’s description of lago, in Shakespeare’s Othello – ‘diseased intellectual activity, with an almost perfect indifference to moral good or evil’ – applies in equal measure to the man who once said that deceiving people gave him a feeling of power. Mark Hofmann was not just a brilliant craftsman, a conjuror of paper and ink who fabricated historical documents with such technical skill that some of the most experienced forensic experts in America could find no signs of forgery. He was a master of human psychology who used hypnosis and mind control to manipulate others and even himself. He was a postmodernist hoaxer who deconstructed the language and mythology of the Mormon Church to create documents that undermined some of the central tenets of its theology. He was successful because he understood how flimsy is the wall between reality and illusion and how willing we are, in our desire to believe in something, to embrace an illusion. When the web of lies and deceit began to unravel, he turned to murder.

We are drawn to those things we are not. Journeying into Mark Hofmann’s world was like descending into a dark pit where all that is most devious and frightening in human nature resides. In the course of that journey I would hear many strange things. I would hear of golden plates inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs, and lizards that talked; of angels and Uzis. I would see the corruption beneath the glittering surface of the auction houses, hear lies masquerading as truth, and the truth dismissed as lies. I would encounter detectives and dissident Mormons; forensic documents experts and cognitive psychologists; shapeshifters and frauds. After three years spent trying to unravel the riddle posed by one of the world’s greatest literary forgeries, I feel that I have come as close to the truth as I can possibly get. It is for you, the reader, to decide what it means.

PROLOGUE The Poet and the Murderer

He thought he had gone under deep enough, but as he followed the curve of the letter m, he felt a momentary tremor like the distant rumbling of an earthquake. It began deep in his cerebral cortex, then traveled along his nerve ends, down his arm, into his hand, until finally it reached his fingers. The tremor lasted only a microsecond, but it was long enough to cause a sudden tightening of the muscles like a rubber band stretching. As he reached the top of the first stroke of the letter m, and the pencil began to plunge back down toward the line, he had felt his hand tremble slightly.

Laying down the pencil, he began to slow his pulse. He relaxed his breathing and counted in patterns of seven as he pulled the oxygen in and out of his lungs. He imagined warmth circulating around his body like an ocean current, and he concentrated on funneling it into his fingertips. As the world contracted to a point between his eyes, he took a fresh sheet of paper and began to visualize the shape of each letter until he could see them laid out on the page in sequence, like an image projected on a screen.

He had spent days practicing her handwriting: the h that toppled forward like a broken chair; the y that lay almost flat along the line, like a snake; and that distinctive t, which looked like an x turned sideways. As he felt himself go deeper into the trance, he began to write. This time he wrote fluently and without hesitation, the letters spooling out of his unconscious in a continuous, uninterrupted flow. It seemed as though she was inside him guiding his hand across the page. As he signed her name, he felt an immense rush of power.

He got up and stretched. It was three in the morning. Upstairs, he heard the baby begin to cry and his wife’s footsteps as she went to comfort him. Crossing the darkened basement, he took down a plastic bag from a shelf where he had hidden it the day before, behind a pile of printing plates. After removing a length of galvanized pipe, he drilled holes into the skin of the cast iron end cap, threaded two wires through the holes, and attached an improvised igniter onto the wires. Then he packed gunpowder into the pipe and threaded on the remaining end cap. In the morning he would drive out to Skull Valley to test the bomb. He got out the two battery packs he had bought some days before at Radio Shack and took down an extension cord from a bracket on the wall. Then he packed everything into a cardboard box. He laid the box next to the poem. It was no great work of art, he thought. But it would do.

CHAPTER ONE Emily Dickinson for Sale

Daniel Lombardo, the curator of Special Collections at the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts, had no idea, as he set off almost twelve years after the events of that night, to drive the fifteen miles to Amherst from his home near West Hampton, that the shock waves from that bomb were about to shake the foundations on which he had built his life.

It was a glorious day in May, and as he made his way over the Coolidge Bridge in his Del Sol sports car, with the top down and his favorite Van Morrison album playing on the tape deck, life felt about as good as it could get. Lombardo loved his job at the library. He was writing a book. He was playing the drums again. His marriage was fulfilling. As he dropped down over the hills toward Amherst, he thought about the announcement he was about to make to members of the Emily Dickinson International Society who had traveled to Amherst from all over America for their annual meeting. If things worked out as Lombardo hoped they would, if he could raise enough money, he was going to be able to make a lasting contribution to the community he had come to call home.

Lombardo vividly remembered the moment when he had first seen the poem. He was sitting at his desk on the top floor of the Jones Library, a large eighteenth-century-style house built of gray granite in the center of Amherst, leafing through the catalog for Sotheby’s June 1997 sale of fine books and manuscripts. Lombardo knew that original, unpublished manuscripts by Dickinson were as rare as black pearls. Indeed, it had been more than forty years since a new Dickinson poem had been found. In 1955 Thomas H. Johnson, a Harvard scholar, had published a three-volume variorum edition, fixing the Dickinson canon at one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five poems. But because of the unusual way that Dickinson’s poems have come down to us – she published almost nothing during her lifetime and was extremely secretive about what she had written (after her death many poems and letters were destroyed by her family) – there has always been a lingering feeling that new material may come to light. The year before, two unknown Dickinson letters had suddenly been found. Who was to say that new poems were not out there, hidden in a dusty attic in Nantucket or the back of a book in a decaying New England mansion?

The poem was listed in the Sotheby’s catalog between a rare 1887 edition of Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, bound in green Morocco leather, and an original watercolor cartoon of Mickey Mouse and Pluto. The catalog described it as an ‘autograph poetical manuscript signed (“Emily”).’ The juxtaposition with Mickey Mouse would have delighted Dickinson, thought Lombardo, as he took out an Amarelline liquorice from the tin he had brought back from a recent trip to Sicily and settled back to read the poem.

It was written in pencil, on a piece of blue-lined paper measuring eight by five inches. On the top left corner was an embossed insignia. And the poem was signed ‘Emily.’ In red ink, at the top right corner of a blank page attached to the poem, someone had also written, ‘Aunt Emily,’ in an unidentified hand:

That God cannot

be understood

Everyone agrees

We do not know

His motives nor

Comprehend his

Deeds –

Then why should I

Seek solace in

What I cannot

Know?

Better to play

In winter’s sun

Than to fear the

Snow

With his elfin features, bushy, russet-brown beard, and shoulder-length hair, Dan Lombardo looks like one of the characters in Tolkien’s The Hobbit. He weighs one hundred pounds and stands five feet two inches tall. Getting up from his desk, he walked over to the imposing, cupboardlike safe standing in the corner of his office. It was taller than he was, made of four-inch-thick steel, and had a combination that only he and the library’s director knew. Inside it were manuscripts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Spinning the wheels of the combination lock until the door clicked open, Lombardo took out several Dickinson manuscripts and laid them on his desk.

One was a letter from 1871. The other was a poem called ‘A Little Madness in the Spring,’ which Dickinson had sent to a friend, Elizabeth Holland, in 1875. Written on the same kind of notepaper, in a similar hand, it bore an uncanny resemblance to the poem in the Sotheby’s catalog. It was even written in pencil and signed ‘Emily’:

A little Madness in the Spring

Is wholesome even for the King

But God be with the Clown –

Who ponders this tremendous scene –

This whole Experiment of Green –

As if it were his own!

Lombardo compared the handwriting. Emily Dickinson’s handwriting changed radically during her lifetime. Yet the handwriting from within each period of her life is generally consistent. Lombardo was not an expert, but the handwriting in both poems looked the same. The tone and content of the poems seemed similar as well. The high-water mark of Dickinson’s poetry had been reached the decade before. By the 1870s the flood of creativity that had given the world some of the most heart-powerful and controlled poems ever written in the English language had begun to recede. Dickinson was in her forties. Her eyesight was failing. Her creative powers were declining. Many poems from this period are just such minor ‘wisdom pieces’ as this one seemed to be.

The fact that the poem was signed on the back ‘Aunt Emily’ suggested to Lombardo that it had been written for a child, most probably Ned Dickinson, the poet’s nephew. In 1871 Ned would have been ten years old. He lived next door to her at the Evergreens, and Dickinson, who never had children of her own, adored him. The feeling seems to have been reciprocated. Ned frequently ran across from the Evergreens to visit his brilliant, eccentric aunt. On one occasion he left his rubber boots behind. Dickinson sent them back on a silver tray, their tops stuffed with flowers.

Perhaps this new poem was a similar gesture, thought Lombardo. He knew she had sent Ned other poems that playfully questioned religious beliefs, like one sent him in 1882. It was also written in pencil and signed ‘Emily’:

The Bible is an antique Volume –

Written by faded Men

At the suggestion of Holy Spectres –

Subjects – Bethlehem –

Eden – the ancient Homestead –

Satan – the Brigadier –

Judas – the Great Defaulter –

David – the Troubadour –

Sin – a distinguished Precipice

Others must resist –

Boys that ‘believe’ are very lonesome –

Other Boys are ‘lost’ –

Had but the Tale a warbling Teller –

All the Boys would come –

Orpheu’s Sermon captivated –

It did not condemn.

The possibility that it had been sent to a child added to the poem’s charm. The image many people had of Dickinson was of a lonely, rather severe New England spinster who spent her life immured in the Homestead, under self-elected house arrest; the quintessential artistic genius, driven by her inner demons. It was how the public liked its artists. The poem showed another side to her that Lombardo felt was more truthful. Instead of the Isolata of legend, she appears as a witty, affectionate aunt sending a few quickly scribbled lines of verse across the hedge to her adored nephew.

Lombardo was particularly excited by the new poem because, although the Jones Library had a fine selection of manuscripts by another former resident of Amherst, Robert Frost, including the original of ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,’ it had only a few manuscripts by the town’s most famous daughter. Almost all of Emily Dickinson’s letters and poems are at two far wealthier institutions: Amherst College, and the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Since becoming curator of Special Collections in 1982, Lombardo had devoted himself to building up the Jones Library’s collection of her manuscripts. The chance to buy a poem that the world had never seen was a unique opportunity.

After looking at the handwriting Lombardo did a cursory check of the paper. For this he consulted the classic two-volume work The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson, by Ralph Franklin, a Yale University scholar widely regarded as the world’s foremost expert on Dickinson’s manuscripts. The poem in the Sotheby’s catalog was written on Congress paper, which was manufactured in Boston. It was lined in blue and had an image of the Capitol embossed in the upper left-hand corner. According to Franklin’s book Dickinson had used Congress paper at two different periods in her life: once in 1871, and again in 1874. The poem in the Sotheby’s catalog was dated 1871. Lombardo told himself that it was absurd to think of buying the poem. The Sotheby’s estimate for the poem was $10,000–$ 15,000. But Lombardo was sure this would climb to as much as $20,000. The Jones Library had only $5,000. But in the days that followed, he became more and more excited at the prospect of acquiring the poem. He felt strongly that Dickinson’s works belonged in the town where she had created them. As William and Dorothy Wordsworth are to Grasmere, in England, or Petrarch is to Vaucluse, in France, Emily Dickinson is to Amherst: an object of pride and an industry. Each year thousands of Dickinson’s fans, from as far away as Japan and Chile, make the pilgrimage to the Homestead. Cafés offer tins of gingerbread baked to her original recipe. Scholars fill the town’s bed-and-breakfasts and patronize its restaurants. The poet’s grave is always decked with flowers.

Some years earlier Lombardo had had the idea of throwing a birthday party for Dickinson. On December 10 children from the town and surrounding area were invited to the Jones Library to wish the poet many happy returns and play games like ‘Teapot’ and ‘Thus Says the Mufti,’ which Dickinson herself played as a child. Dressed in period clothes – a top hat, burgundy-colored waistcoat, and leather riding boots – Lombardo would tell the children about the poet’s life, and how it connected to the town.

Lombardo did not have children himself, so he always enjoyed the occasion. At the end of the party one of the other librarians would appear from behind a curtain, dressed in a long white pinafore dress, black stockings, and black shoes. Of course, the older children knew it was just the librarian, dressed up in funny clothes. But he could tell by the light shining in the eyes of some of the younger children that they really believed it was Emily Dickinson herself. That’s what Dan liked to think, anyway.