скачать книгу бесплатно

‘Leonard Whelan.’ Nancy’s father holds out his hand. He’s a tall, slim man with an angular face and silver hair, impeccably dressed in a grey suit, with a gold half-hunter watch peeking out of his waistcoat. ‘LJ. To family.’

‘LJ it is, then. Pleased to meet you.’ Martin pauses, unsure. They give each other a firm handshake. Test one, passed. LJ ushers him over to an armchair. As he lowers himself into it, something sharp sticks into his buttocks and he leaps up; a pair of silver knitting needles poke out of the cushions.

‘Oh, I’m so sorry!’ Peg rushes over, lifts the cushion, and pulls out the knitting needles, a ball of red wool, and a pattern book.

Nancy comes back in with a vase for the flowers, just in time to see the rumpus.

‘It’s fine.’ Martin chuckles. ‘I’m well cushioned.’

A ripple of laughter goes round the room. LJ goes over to the drinks cabinet. ‘Sherry?’

‘Please!’ Martin nods.

Over the fireplace, there is a small painting: a harbour scene, with brightly coloured boats. An upright piano stands in the corner. Next to it is a music stand with a flute resting on it. Sheet music.

‘Mummy and Daddy play duets,’ Nancy explains.

‘Piano. Badly.’ Peg points at LJ. ‘Flute.’

‘Nancy has a beautiful singing voice.’ Her father beams.

‘A musical family.’ Martin smiles at Nancy.

‘My family make pianos.’ Peg lights a long, slim cigarette, coughs. Nancy looks at her, askance. ‘Squires of Ealing? Perhaps you’ve heard of them?’

Martin looks blank. ‘No, I’m sorry.’

‘We’re not well known, like Bechstein or Steinway. But they have a nice tone.’ LJ pulls a pipe from his pocket, a packet of St Bruno, pinches a measure of tobacco between his thumb and forefinger, presses it into the bowl of the pipe, tamps it down, strikes a match, puffs contentedly. He looks over at Martin. ‘Terrible news coming out of Germany.’

‘Shocking . . . ’ Martin is momentarily tongue-tied. ‘I think Chamberlain has acted disgracefully.’

Peg adroitly changes the subject. ‘How’s your Aunt Dorothy?’

‘Jam-making.’

‘My damson wouldn’t set.’ Peg smooths her skirt, takes another puff of her cigarette, coughs. ‘Not enough pectin, I think.’

Nancy waves the smoke away. ‘Mummy, must you? You know it’s bad for your asthma.’

LJ sucks at his pipe. ‘Nancy tells me you’re at Oxford?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Martin squares his shoulders. ‘Law and Modern Languages.’

‘You must be very busy.’ Peg stubs out her cigarette.

‘Teddy Hall, isn’t it?’ LJ lets out a ring of blue smoke.

Martin nods. He wants to take Nancy in his arms and swing her out of the door.

‘We lived in Oxford before we came here.’ LJ puffs away. ‘Nancy loved every minute of it, didn’t you, pet? Concerts, the Playhouse, punting on the river.’ He reaches forward and taps the bowl of the pipe on the ashtray. ‘So, what are your plans?’

‘After I graduate I’ll look for work in a law firm, I suppose.’

‘I mean today.’ LJ sucks on his pipe again.

‘We’re going for a picnic.’ Nancy looks across at Martin. ‘So we’d better get our skates on – or we’ll miss the sun!’

Outside Blythe Cottage, Martin opens the door of the Bomb and watches as Nancy turns sideways, lowers herself into the car, swings her feet in after her and smooths her dress over her knees in one fluid movement, like water sliding through a mill race, except Scamp is kissing her face. She’s wearing a new hat: a red, Robin Hood-style cap.

‘Is that new?’ He knows girls love you to notice their clothes.

‘Do you like it?’ She tilts her head to the side. ‘It’s French.’

‘Je l’adore.’ He closes the door after her, runs around to the other side, lifts Scamp off the seat and tosses him in the back.

‘Poor old Scamp.’ Nancy reaches back to pet him, as the Riley takes off, like a racehorse. At the corner, Martin presses the clutch, slips the gearstick out of fourth, revs the engine, double declutches, slides it into third, swings through the bend, accelerates, shifts up. Hedges scroll past. The sun breaks through the clouds. A herd of brick-red Hereford cattle amble across a field. Martin slows, then turns right down a narrow lane. The branches of the trees meet overhead, like the ribs of a Gothic cathedral.

Nancy giggles, holding on to her hat to stop it from flying off. He leans over and kisses her on the cheek.

‘Did I pass the test?’

‘The knitting needle test?’ Nancy’s laugh is snatched by the wind. ‘Definitely.’

At the village of Penn, Martin cuts the engine and clambers out of the Bomb. Scamp races off, in hot pursuit of rabbits. Martin grabs a tartan rug and they set off down a footpath towards Church Path Wood.

Deep in the wood, there is an ancient oak tree. Roughly the same distance from Blythe Cottage as Whichert House, it is the perfect cover for their trysts. Some say the oak dates back to the time of the Spanish Armada, more than four hundred years ago. It’s not the most beautiful tree in the wood. The oak’s limbs are crooked with age, like the arthritic limbs of an old man. There are gnarly lumps on its branches. Whole sections no longer bear leaves. But they have come to love the tree, as a friend and protector.

On one side of the trunk is a heart-shaped hole from a lightning strike. The wood is still blackened, though the seasons have long since washed away any trace of soot or charcoal. On stormy days, they have sometimes squeezed inside and stood pressed against each, kissing and giggling in the dark, like two children playing in a cubbyhole under the stairs, as the wind shook the leaves above their heads and the branches creaked and scraped against each other.

Martin spreads the rug under the tree and they lie down, staring up through the canopy of leaves. A cloud floats across the sun, the sky blackens and a few drops of rain begin to fall. Nancy pulls her cashmere cardigan tighter around her.

‘What do you want to be . . . ?’ Nancy lets the question hang in the air.

‘ . . . when I grow up?’ Martin laughs.

‘Well, let’s start with when you leave Oxford.’

‘I don’t want to be a lawyer, for a start.’

‘That’s what you’re studying, isn’t it?’

‘I know. But I find it so dull.’ He sits up and lights a cigarette. ‘I’d love to write . . . ’

‘Poetry? Like your uncle?’

‘Not sure I have the talent.’ He blows a smoke ring, then swallows it. ‘How about you?’

‘I think I can confidently predict that typing in an insurance office is not going to be my life’s work.’ She sits up next to Martin, clasps her knees. ‘By the way, I got that part I auditioned for in London.’

‘That’s wonderful.’ Martin enthuses. ‘With the Players’ Company?’

Nancy nods. ‘It’s just a small, walk-on part. But I’ll have to attend the rehearsals, so I’ll get a chance to see how it’s all done. Luckily, they’re all in the evening.’

They fall silent, each lost in their thoughts. Then Martin reaches over and kisses her. Nancy closes her eyes and lies back. His kisses become more passionate, and he begins to slide his hand up her thigh. She pulls away, but he grabs her and carries on trying to reach up under her skirt.

She sits up abruptly and straightens her clothes. ‘Tino, we’re at the beginning of a journey.’ She takes his hand and strokes it. ‘There is so much more to find out about each other.’ She kisses him on the tip of his nose. ‘And if we go too fast, then the happiness . . . ’ she looks into his eyes ‘ . . . and pleasure that could be ours – should be ours – might be spoiled.’ She knits her eyebrows together. ‘I want us to be special.’

‘Me, too,’ Martin replies. He pulls a slim volume of poetry out of the picnic basket, searches for the page. She lies back, staring up into the branches of the hollow oak. A wood pigeon coos, as Martin reads, clear and unfaltering from ‘Our True Beginnings’ by Wrey Gardiner.

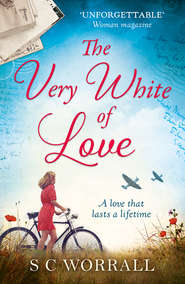

Her hands are clasped in the blue mantle of heaven

And the sea, her haven, is flecked with the white of love

‘That’s how I feel about us.’ He brings his lips to hers, his heart thumping in his chest at what he is about to say. ‘I love you.’

‘I love you, too.’ Nancy kisses him. Deep and long. ‘The very white of love.’

12 NOVEMBER 1938 (#ulink_3827b6eb-fe34-5c33-98f6-4794db68efe1)

London (#ulink_3827b6eb-fe34-5c33-98f6-4794db68efe1)

Familiar stations flash by in a blur of rain. Seer Green and Jordans. Gerrards Cross. West Ruislip. Martin has managed to get back to Whichert House for another weekend before term ends in December. They sit side by side, legs touching, hands clasped. It’s Nancy’s daily commute to her job as a secretary at an insurance firm in Holborn. Now he is sharing it with her. At Marylebone, they get on the bus to Oxford Circus, sit up top in the front seat, like excited children, watching London scroll across the glass screen of the double-decker’s window. She has a new outfit: a little black dress, with a grey velvet jacket, which makes her look like a film star. She points out her favourite landmarks. This is her city, Oxford his. Each stone, each street has a story, a story they are becoming part of together.

‘Us on a bus . . . ’ Martin starts to hum a tune by his favourite jazz artist, Fats Waller. Nancy joins in.

Riding on for hours

Through the flowers

When the passengers make love

Whisper bride and groom

That’s us on a bus

They run down the stairs, laughing, and jump off the bus. But they are soon wrenched back to the dark clouds of the present. As they walk through Soho, a man in a threadbare overcoat bellows the Evening Standard headline: ‘Night of the Broken Glass. Read all about it!’

Martin counts out a handful of coppers, points to the headline. ‘At dinner the other evening, one of the college tutors was saying that all this about the Jews is propaganda by the Rothschilds and the rest of the bankers.’ Martin frowns. ‘To drag us into a war with Hitler.’ Martin shakes his head. ‘There are loads of students, too, who think Hitler is the best thing since tinned ham.’ Martin indicates the newspaper headline. ‘Tell that to my uncle, Philip Graves.’

‘The foreign correspondent?’ Nancy sounds impressed.

‘Yes. He was one of the people who helped expose that hateful book, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, as a forgery!’

Nancy nuzzles against him. ‘You come from such a talented family.’

‘Somehow it seems to have bypassed me.’

‘You got the looks.’ She kisses him on the nose.

They have an hour until the performance begins. Nancy is taking him to a musical revue at the Players’ Theatre Club, in King Street, the company where she has got a small part in a production next season. They are making waves on the London theatre scene. Churchill is a fan and, through rehearsals, Nancy is meeting the actors, including the famous comedienne, Hermione Gingold.

She leads Martin through a warren of streets, their shoes keeping time together, his chunky Church’s brogues next to her tiny, brown boots, their soles touching the same pavement. Love is opening new paths, streets he would never have known if it were not for her, fields where they have walked hand in hand, cafés and bookshops he would never have entered without her, places that are now special to him because of her. And as they walk side by side, he thinks about the thousands of other places that they will visit, the lakes they will see, footpaths they will tramp. England. France. Perhaps Italy. Shared journeys stretching into the future.

‘How about this?’ She has stopped in front of a little Italian bistro on Greek Street: a bog-standard Italian with red and white check tablecloths; cheap Chianti in straw-covered bottles; framed photos of Italian tourist spots; wicker baskets of day-old bread. Martin stares at her reflection in the window. Another place, transformed by love.

‘Perfect.’ He puts his arms around her and turns her face towards his, bends and kisses her: a kiss that seems to go on and on.

They take a table by the window, it’s so cramped Martin hardly fits on his chair, but they have their backs to the other diners and can look out onto the street, watching their own private Movietone of London in 1938.

Nancy orders linguine with clams in a red sauce. Martin chooses lasagne. They share a salad – chunks of spongy tomato, wilted lettuce, some slivers of red onion, brown at the tips. As the tines of their forks touch, they burst out laughing, reach across the table, kiss. Then Nancy pulls away, her face suddenly anxious.

‘Do you think there’ll be another war, Tino?’

It’s a question that has been secretly nagging at Martin ever since Hitler invaded the Sudetenland, like toothache. But, until now, he has not shared his fears with Nancy. ‘I hope not.’ He squeezes her hand. ‘We have so much ahead of us.’

‘But I am not sure appeasement will work.’ Nancy frowns. ‘Not with Herr Hitler. He’ll just take it as a sign of weakness.’

‘I agree.’ Martin leans forward, intently. ‘What we need is tough, military sanctions. But through the League of Nations.’

‘Has the League of Nations actually achieved anything?’ Nancy regrets saying it as soon as the words leave her mouth.

‘I know that’s what people say.’ Martin’s eyes blaze. ‘But if you look at their track record, they’ve actually done a lot for peace. And, I mean, what else is going to stop barbarism from occurring?’

Nancy twizzles some pasta onto her spoon. ‘You know, when I was studying in Munich in 1935, we saw Hitler at the opera.’

‘Really?’ Martin is bug-eyed.

‘Mummy watched him through her opera glasses.’ Nancy grimaces. ‘Said he had beautiful hands. Pianist’s hands.’

The idea that Hitler has beautiful hands seems incongruous and repellent for a man who was currently tearing up the peace in Europe. But Martin says nothing.

‘You remember that little painting that hangs over the fireplace at Blythe Cottage?’ Nancy lays down her fork and spoon.

‘The seascape?’ Martin pours them both a glass of wine.

‘It’s by an Italian painter I got to know when I was living in Munich.’ She takes a sip of wine. ‘Jewish Italian. Paul Brachetti.’

‘Rhymes with spaghetti.’ Martin reddens with embarrassment at his lame joke.

‘He was almost twenty years older than me.’ She takes up her spoon and fork and digs at her pasta.

‘In love with you, no doubt.’ Martin squeezes her knee.

Nancy ignores him by twizzling her fork and spoon. ‘He used to call me his little English rose,’ she says. ‘We would meet for coffee in the English Gardens. Talk about El Greco, his hero. God’s light, he called it.’ She smiles at the memory, then her face darkens, as though a shadow has passed across it. ‘One day, he arrived in a terrible state. They’d broken into his studio, smashed his paintings, daubed swastikas on the walls.’ She reloads her fork with spaghetti. ‘His paintings were what they called entartet. Decadent.’ Her laugh is a staccato howl. ‘Seascapes!’ She takes another sip of wine. ‘Three days later, we met again. A café near the station.’ Nancy lays her napkin on the table, a faraway look in her eyes. ‘He was carrying a battered suitcase and some parcels, wrapped in newspaper. His hair was a mess, his eyes were bloodshot.’ Her pupils darken. ‘He’d come to say goodbye.’ Nancy’s voice quivers.

‘Where did he go?’

‘He said he would try and get to Spain, first.’ She smiles. ‘He wanted to seeToledo, where El Greco learned about light. Then Lisbon. Maybe a ship to America.’ She looks across at Martin, tears in her eyes. ‘I tried to give him some money. But he wouldn’t hear of it.’