скачать книгу бесплатно

The first woman to circumnavigate the world

Homeward Bound

Molly, Daisy and Gracie’s 1,600 km walk following a rabbit-proof fence in Western Australia

Finding Petra

Johann Burckhardt’s discovery of the fabled city

Trail of Tears

The forced migration of the Native American Tribes

Around the World on a Bike

Annie Londonderry’s ‘cycle’ around the world

Unlocking the Islamic World

The travels of Ibn Battuta

Walk the Amazon

Ed Stafford: Amazon odyssey

Natural Born Explorer

Naomi Uemura and his solo winter ascent of Denali

Marathon Man

Amputee, Terry Fox’s incredible run across Canada

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

Challenger Deep: Descent to the lowest point on Earth

The Trials of the Wager

George Anson’s voyage of pride and greed

Company Man

Abel Tasman: First white man to set foot on Australian soil

The Northwest Passage

Sir John Franklin’s search for a sea route to the Orient

Into the Empty Quarter

Wilfred Thesiger’s travels in Arabia

Across Siberia

Cornelius Rost’s escape from a Siberian Gulag

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements and photo credits (#u6e2df91c-7acd-53b7-8da5-619df564b688)

About the Publisher

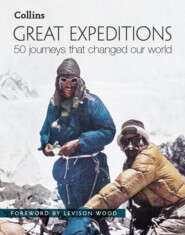

Khumbu valley, Nepal. Mount Everest is behind the Khumbu Glacier on the left side of the picture.

Foreword (#ulink_50d4bc25-ca35-5814-94cf-638c7483c7a1)

With the advance of modern technology our world seems smaller. We have apps that can translate a phrase at the touch of a button, travel is more affordable and new places can be discovered by swiping a screen. Yet there is still so much to be discovered. What has not changed since early explorers set out with little more than a map is the spirit required to undertake an expedition; the love of a challenge and the mental and physical toughness a person needs to call on when things may not be going their way. Exploration is about more than putting a flag in a map. It’s about the experiences that change us and the people we meet along the way.

I have found over the years that the best way to travel and explore is on foot. There’s nothing like treading the paths and tracks to get a real impression of a country, its landscape and its culture. The many explorers who went before me didn’t have helicopters on hand or gadgetry to make their lives easier. Whether they were trekking the banks of the Nile or scaling peaks in the Himalayas; breaking new trails in the jungles of Asia or crossing unknown deserts, it was these early pioneers who inspired me.

David Livingstone’s journey to find the source of the Nile was a large part of the motivation behind my own nine-month expedition walking the length of the world’s longest river. It was reading about these adventures as a young man that set me on my path, starting in the army and eventually undertaking world-first expeditions of my own. Like Livingstone, I was also documenting my journey, keeping scribbles in a notebook rather similar to the one he used. But then again, I was able to use technology such as cameras he could only have dreamt of. We were both creating our own records of a shared experience more than 150 years apart.

As I have learned, modern day expeditions are not immune to danger. Whilst the promise of a helicopter can give the impression of a safety net, there is still a huge risk for anyone undertaking a remote climb or trek. Nature, whether it’s driving winds, freezing temperatures or intense heat, poses just as much risk today as it did a hundred years ago. The results can be tragic, as anyone who followed Walking the Nile will know. For early explorers such as Amundsen, Shackleton and Nansen, the Poles proved the ultimate challenge. Things inevitably go wrong but it’s at these times that a person can show what they’re made of. This book is a celebration of the few brave people who defied terrible odds and conditions to prove something vital to both the world and themselves. For every risk, the rewards are huge.

The stories featured in this book form an extensive list of human achievement that has had a huge impact on the world today. No space mission has quite captured the imagination of the world like the Apollo 11 moon-landing or had such a profound impact on science as Charles Darwin’s voyages. Sometimes these stories, such as the Challenger journey to the deepest point on Earth, are so extraordinary they can seem like science fiction. Personally, the expeditions that I love are the long-distance overland journeys, such as those by the intrepid Frenchwoman Alexandra David-Néel who in 1924 crossed the Himalayas in midwinter and entered a forbidden Tibet in native disguise. Perhaps less well known, but an achievement that deserves to be recognised.

There is still much to explore and plenty of experiences to be had, and I am sure that within our lifetime we will see more Great Expeditions that are just as impressive as the ones detailed in this book. I for one hope to keep following in the footsteps of the explorers who have gone before.

LEVISON WOOD

The Giant Leap (#ulink_6f019f30-bf96-549e-8943-aae77dac3b38)

Apollo 11 and the Moon landings (#ulink_6f019f30-bf96-549e-8943-aae77dac3b38)

“The ‘a’ was intended. I thought I said it. I can’t hear it when I listen on the radio reception here on Earth, so I’ll be happy if you just put it in parenthesis.

Neil Armstrong commenting on his own quote and the most famous space line ever spoken: ‘That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind’.

WHEN

July 1969

ENDEAVOUR

Putting a man on the Moon

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

The crew risked death by accident, fire, solar radiation and even drowning on their return to Earth.

LEGACY

The crew achieved perhaps the single greatest ‘first’ in human history. The Apollo program transformed the fields of astronomy, aerospace and computing, and put space at the forefront of our collective imagination.

Official photo of Apollo 11 crew (left to right): Neil Armstrong, Commander; Michael Collins, Command Module Pilot; and Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin Jr., Lunar Module Pilot.

The first step on the moon by a man was also the last of an eight-year odyssey by the largest expedition team in human history. On 20 July 1969, Neil Armstrong had travelled 384,000 km (240,000 miles) in four days – the equivalent of nine circumnavigations of the Earth – through the deadly vacuum of space. But the Apollo program that put him there had employed the skills of 400,000 people for nearly a decade. More than 20,000 companies and universities had supplied equipment and brainpower. The project cost $24 billion and was easily the largest and most technologically creative endeavour ever made in peacetime. It was nothing less than the longest, most dangerous and most audaciously conceived expedition the world had ever seen. The catalyst was the singular vision of one man.

Race into space

On 12 April 1961, the Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space. Just eight days later, US President John F. Kennedy (who had only been in office for three months) wrote this in a memo to his Space Council:

‘Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?... Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs? If not, why not?’

His choice of words – ‘beating’ and ‘win’ – made it very clear that he was intent on winning the Space Race.

Apollo takes to the skies

At this point, the United States was lagging behind the Soviet Union. One American astronaut, Alan Shepard, had flown into space, but he had not achieved orbit. The first Russian Sputnik craft had orbited the Earth in 1957.

NASA was given the funds to launch a completely new space program – Apollo – dedicated to achieving Kennedy’s stated goal ‘before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth’. A new Manned Spacecraft Center (nicknamed ‘Space City’) for human space-flight training, research, and flight control was built in Houston, Texas. A vast launch complex (now known as The Kennedy Space Center) was built near Cape Canaveral in Florida.

Hundreds of the planet’s greatest scientific brains would spend the coming years solving seemingly impossible problems at breakneck speed, to create a rocket and spacecraft that could get a crew into orbit, then onwards to the Moon, down to its surface, and then repeat all these steps in reverse.

The program suffered a serious early setback. The Command Module of Apollo 1 caught fire on 27 January 1967, during a prelaunch test, killing astronauts Virgil Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee. But NASA learned from the disaster and went back to the drawing board to make their craft safer. In December 1968, the second manned Apollo mission, Apollo 8, was successfully launched. It became the first manned spacecraft to leave Earth orbit, reach the Moon, orbit it and return safely to Earth. After two more successful launches, Apollo 11 was cleared for launch on 16 July 1969.

A Saturn V rocket blasts the Apollo 11 mission towards the Moon on July 16, 1969. Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin Aldrin are in the cone-shaped Command Module in the middle of the picture.

Sitting in their tin can

On 16 July, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin and Michael Collins strapped themselves into Columbia, the command module of Apollo 11. This tiny conical cabin would carry the three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an ocean splashdown eight days later. Connected to the bottom of the command module was the cylindrical service module, which would provide propulsion, electrical power and storage during the mission. Below that was Eagle, the lunar module that would make the actual descent to the Moon’s surface.

Their tiny habitat was bolted on to the top of a colossal Saturn V rocket. At 111 m (363 ft) high, Saturn V stood 18 m (58 ft) taller than the Statue of Liberty. It is still the tallest, heaviest, and most powerful rocket ever built.

The Saturn V rocket being prepared and taken to the launch pad in 1969.

‘But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic?

.........

We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win…’

President John F. Kennedy

The journey between worlds

The gargantuan engines roared for eleven minutes, burning 2 million kg (5 million lb) of liquid oxygen and kerosene at over 13 metric tonnes per second to hoist the three astronauts into the heavens.

Two and a half hours after topping 40,000 km/h (25,000 mph) and reaching orbit, another rocket burn set them on course for the Moon. The astronauts spent the next three days coasting through the void. On the fourth day they passed out of sight behind the Moon and fired rockets to ease them into orbit 100 km (62 miles) above the dusty surface.

Armstrong and Aldrin climbed into the Eagle and said farewell to Collins. He would remain alone in Columbia in orbit while his colleagues walked on the surface. The landing craft separated and for twelve minutes a computer guided Armstrong and Aldrin down. Fear flashed through mission control five minutes into the descent when Aldrin instructed the computer to calculate their altitude and it blinked back an error message. Should they abort? Engineers coolly worked out that it was safe to override the message and go on.

But just a few minutes later there was further cause for alarm. Armstrong saw that the crater the computer was piloting the Eagle into was strewn with large boulders. He took manual control and guided the craft further downrange, burning extra fuel. When the Eagle finally touched down in the Sea of Tranquility, it had a mere 30 seconds of fuel left.

The Lunar Module ascends from the Moon with Earth just above the horizon.

Men on the Moon

Touchdown was the softest landing that the pilots had ever experienced. Lunar gravity is one-sixth of that on Earth, and the astronauts felt no bump on landing — they only knew they were definitely down when a contact light came on.

‘Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!’ said Armstrong, unquenchable joy surging in his normally cool voice. But rather than step outside straight away, Armstrong and Aldrin spent the next four hours resting in the cockpit. They yearned intensely to get outside but were also full of trepidation. Would their spacesuits protect them from the vacuum? Would they be able to take off again?

The Eagle landed in the Bay of Tranquilitity, top right on this spectacular image of our Moon.

The time had come. Neil Armstrong stepped out of the Eagle, descended the ladder and walked on the moon, 109 hours and 42 minutes after he had left planet Earth. An estimated 530 million people watched Armstrong’s televised image and heard his voice describe the event as he took ‘...one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind’. After 20 minutes, Aldrin followed him and became the second human being to make footsteps in moondust.

An astronaut’s boot print in moondust.

The astronauts put the TV camera on a tripod about 9 m (30 ft) from the lander to transmit their actions. Half an hour into their moonwalk, they spoke to President Nixon by telephone. The two astronauts spent the next two and a half hours collecting rock samples, taking photographs and setting up experiments. As well as planting a US flag, they also left a Soviet medal in honour of Yuri Gagarin, who had been killed in a plane crash the year before.

Armstrong and Aldrin were on the Moon’s surface for 21 hours and 36 minutes. This included seven hours of sleep. The ascent stage engine fired successfully and they lifted off, leaving the descent module behind. Just under four hours later, Eagle docked with Columbia in lunar orbit, and the three crew were reunited. Columbia headed home. Three days later, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins fell back to Earth as heroes.

The Times reports the start of the astronauts’ return journey.

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew home with a ticker tape parade down Broadway and Park Avenue.

Next stop, the stars

This astonishing achievement inspired a whole generation with the technical and creative possibilities of space. The Apollo program brought 382 kg (842 lb) of lunar rocks and soil back to Earth, transforming our understanding of the Moon’s geology and history. The program funded the construction of the Johnson Space Center and Kennedy Space Center. Huge advances in avionics, telecommunications, and computers were made as part of the overall Apollo program.

The Apollo 11 Command Module on display at Cape Canaveral.

Politically, the Space Race was won – decisively – by America. JFK had been assassinated six years before his dream became reality but the Soviets had been beaten, as he had wanted.

Apollo 11 was the first in a flurry of launches. Apollo 12 became the second successful mission to the Moon just four months later, in November 1969. Apollo 13 famously had a malfunction on the journey out and had to return home without touching down on the Moon. Apollos 14 to 16 all landed safely on the lunar surface. In December 1972, Apollo 17 was the sixth – and final – manned spacecraft to make a Moon landing. In total, twelve Apollo astronauts walked on the Moon. No humans have gone further than Earth orbit in the decades since.

One of the most unexpected glories of the expedition was actually an image of home: the extraordinarily delicate beauty of the blue Earth as seen from our natural satellite. It was a sight that few had imagined but which utterly transfixed all astronauts who witnessed it.

President Barack Obama welcomes Apollo 11 astronauts Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin (left side) and Neil Armstrong’s widow, Carol (seated third from the right), to the Oval Office on 22 July 2014. Also seated are NASA Administrator Charles Bolden and Patricia Falcone, Director for National Security and International Affairs.

Race to the South Pole (#ulink_8f3c2ee6-c2e9-5a5d-b4cd-581e5c19faa2)

The expeditions of Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott (#ulink_8f3c2ee6-c2e9-5a5d-b4cd-581e5c19faa2)

“I may say that this is the greatest factor – the way in which the expedition is equipped – the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order — luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.

From The South Pole, by Roald Amundsen