скачать книгу бесплатно

Visitor passes were issued and the gates opened. Usually all vehicles were left outside, but this one had special dispensation. A young woman in a crisp white coat came to meet them, and Pete’s face lit up as they introduced themselves. He settled her in the middle seat of the car and spent a lot of time helping her with her seat belt. Her perfume was a welcome addition to the heady atmosphere of the vehicle, and she directed them to a remote area of the camp where three portacabins were sited. Each had a large generator parked outside, feeding the cabin with a mass of cables of various thicknesses.

The portacabins were unique. They had no windows and were lined with wire mesh. This was to ensure that no radio signals could enter or escape . Pete was too busy talking to the girl to notice, but Tony took it all in.

‘Ah, Captain Grey and Staff Sergeant Watkins, so glad you could make it.’ A tall man in his sixties with an unruly mess of thinning white hair and equally untidy eyebrows met them at the door and shook their hands vigorously. The white coat he wore was covered in small burn holes, and his top pocket was stuffed with spectacles and an assortment of pens. His identity pass was pinned on the other side, displaying a picture of a younger man.

‘Tea or coffee, gentlemen? How do you take it?’

Tony ordered for the pair of them. ‘Both tea just with milk, please.’

Dr Jenkins turned to the young assistant, and in his thick Yorkshire accent requested, ‘Two teas, Susan. Standard Nato.’

The interior of the cabin was well lit by an unusual number of ceiling lights. Down each side were benches loaded with display screens, meters and soldering irons. Each bench had a rack containing rolls of multicoloured wires of variable diameters, with little square storage bins containing nuts, bolts and washers stacked at the back.

‘Sorry for the delay at the guardroom, but we cannot have telephones in here. The whole cabin is screened so we get accurate readings, and nothing can influence our delicate electronics.’ He led them past a maze of cables and dexion cabinets, stopping at a large, untidy bench. Kit had been brushed aside to make room for a tube of aluminium twelve inches long and two inches in diameter. The untidy pile of tools, heaped boxes of grub screws and meters formed an amphitheatre around the tube, giving it presence. This is what they had came to see.

Standing close, with blobs of solder and wire snippets underfoot, they looked down expectantly. At first glance they were slightly disappointed at the unassuming-looking object, expecting something more elaborate, thinking, Could this object fulfil our requirements?

‘This, gentlemen, will stop us losing the war.’ The doctor picked up the tube with loving care and started explaining its virtues. Once he got going it was hard to keep pace with him. He went into great detail describing the difficulties that had to be overcome and the amount of work that went into producing the innocent-looking cylinder.

‘The frequencies involved were in the 3 to 4 Hz band . . .’ Peter sat down on the only stool available and Tony leant on the bench, trying to follow the technical jargon. ‘Reducing the circuitry so it would fit inside the dimensions you gave me was the greatest challenge I have had to face in my forty years in this establishment.’ Scarcely pausing for breath, the doctor hurried on. ‘The coaxial condenser needed to be compatible with the zynon 3-mm . . .’ He spoke mainly to the cylinder only, occasionally looking up at the bewildered couple. ‘. . . tredral activator.’

Peter sneaked a look at Tony, searching for evidence of understanding. Their eyes met, forcing them to exchange a huge grin as the doctor continued to baffle them. There was a momentary pause as the tea arrived, and the heap of kit was further rearranged to make way for the mugs and the plate of biscuits.

‘To put it simply, gentlemen, if this device is placed in the correct position it will do everything you have asked me to achieve.’ Even a mouthful of chocolate digestive couldn’t stop the flow of information. A spray of crumbs now accompanied his briefing. ‘It is turned from a solid block of aircraft-grade aluminium. Virtually indestructible. . .’ At last he stopped for a swig of tea. ‘Any questions?’

‘How is it powered, and how long will it last?’ asked Tony.

Thoughtfully the doctor drained his cup before answering, fondling the tube obscenely. ‘To put it simply, it operates like a self-winding watch. Any movement will charge the circuits that lie dormant when motionless. There is an oscillating trembler switch. The whole tube is filled with epoxy resin. This protects the circuits and components, making them virtually indestructible. They’re not affected by vibrations or G force. The end cap has a 3-inch fine thread and is bonded with a heated adhesive when screwed on, making it stronger than a weld. Once sealed it cannot be opened.’

‘What about the effect of climate? What is its operating range?’ asked Tony. Now that Susan had joined them, Pete seemed less interested in the device.

‘The coefficients of all the materials are compatible within a micron. We have heated it in an oven for twenty-four hours and had it in a deep freeze with no adverse effect. The resin has a melting point of 3,000° Celsius and a freezing point that we cannot determine in this laboratory’.

‘If it’s sealed, how do we turn it on?’ queried Tony.

‘In here is a transponder that activates when it receives a signal. It powers up all the circuits. These are duplicated just in case one fails. Two micro-capacitors . . .’ and so it went on.

‘Can I hold it, please?’ The doctor hesitated slightly before handing the tube over. ‘What’s this arrow for?’ queried Tony, pointing to a small engraving at one end.

‘Ah, that’s to ensure that when they are in transit all the arrows face the same way to ensure that they will not become accidentally excited or activated. I will enlarge on this later.’

‘Now for the million-dollar question: How do we fix it?’ asked Tony. Pete still seemed keener to talk to Susan than the doctor. ‘Feel the weight of this, Pete.’ He handed over the device, trying to get him interested and include him in the conversation.

‘Follow me.’ The doctor led the way to the back of the cabin, where a scaffold pole was held in a vice clamped to a bench. Holding the device two feet from the scaffold pole, he continued his briefing. ‘The inside of the cylinder is lined with a multiple layer of ceramic magnets. We borrowed this idea from the space chappies at NASA. Just watch as we get closer.’ He inched the device nearer to the pole, building up the tension like a music-hall entertainer. ‘Look at it now.’ He gripped the device in both hands, and as it got within three inches it started shaking. At less than an inch he let it go; it leapt the gap and firmly clamped onto the pole. ‘There we go: snug as a bug in a rug. Try to prise it off,’ he offered.

Tony and Peter took it in turns to try and remove the cylinder, and only succeeded when they worked together.

‘That’s amazing,’ said Peter. ‘I’m really impressed.’ They both stood there thinking the same thing: This is all too good to be true. It is so simple there must be some drawbacks. They were both experienced in the use of modern technology, and wary of it. It was great when it was working, but anything that can go wrong usually does, especially when the pressure is on. Simplicity is the key, and this device, although very sophisticated on the inside, was simplicity itself. They were both lost for words trying to think up snags or shortcomings.

The doctor left them to their thoughts and gave them time to discuss things between themselves. He retired to the first bench and opened a drawer, removing a sheath of papers. ‘Is there any tea left in the pot, Susan? I could murder another cup.’ With his glasses balanced on the end of his nose he looked every inch the mad professor. He shuffled a pile of forms and papers, occasionally writing in a notepad. He wrestled with sheets of carbon paper, and kept dropping them on the floor. As he stooped to pick one up he would drop his pen; he spent a lot of time arranging the paperwork to his satisfaction.

Susan returned with a tray full of fresh tea and Peter needed no second invitation to join her at the bench, leaving Tony deep in thought, still playing with the cylinder. While the doctor was recovering a piece of paper from the floor he found a small grub screw. ‘Do you know I looked everywhere for this?’ he exclaimed.

Tony joined them and handed over the cylinder. ‘Come on, doc, there must be some snags. This looks all too simple.’

‘The only snag or drawback as I see it is accurate placing. Because of the size limitations everything is minimal, and proximity to the signal source is paramount.’ As he spoke he rhythmically tapped the device in the palm of his hand. ‘I believe you are now going on to Shrivenham where they will advise you on placement.’

‘Yes we are due there this afternoon,’ replied Peter. ‘Everything is happening at once.’

‘I have got the paperwork sorted. This is the hardest part of the project for us. I am well over budget and have used up the entire department’s overtime allowance. I would rather go with you than face those paper-pushers over the road. What about you, Susan?’

Before she could answer Pete chipped in, ‘We would love to have you along.’

‘Susan, can you put this one with the others, please.’ The doctor handed over the aluminium cylinder. ‘Gentlemen, the only thing I can add is that you must ensure that in transit you have all the arrows facing the same way. We have tested the device thoroughly in the laboratory, but to a very limited extent in the field. We just have not had the time. What do you think, Captain? Will it do?’

Peter’s gaze followed the girl as she walked to the door and busied herself packing away the device with all the others. He noticed the absence of make-up and the neatly swept-back hair. There was a pregnant pause as the doctor waited for an answer.

Tony came to the rescue. ‘Thank you for all your help, Doctor. We certainly didn’t expect you to come up trumps so quickly.’

A sly dig in the ribs got Pete’s attention and he took over. ‘Yes, thank you very much. It is now up to us.’

‘We wish you the very best of luck. Sign here for the thirty-six devices, and again on the bottom of the pink form. Let me sign your passes and remember to surrender them at the gate.’

Tony backed the vehicle up to the cabin and loaded the boxes while Peter chatted to Susan. ‘Come on, you old Tom,’ he called out. ‘We must be going. The wife and kids will be missing you.’

It was Pete’s turn to drive. ‘Did you see her eyes? They were lovely.’ He jumped hard on the brakes to slow down for the sleeping policeman.

‘Why is it that every time you meet a woman you fall in love, and why is it that every time there’s work to be done . . .’ The two argued good-naturedly for several miles, with Pete discussing the girl and Tony the device, before lapsing into silence. They were heading back west but had a short detour to make which would take them to the Royal College of Science, Shrivenham. Tony tried to sleep but Peter thought he was driving his Caterham 7, and was throwing the car around with gay abandon. Tony gave up the idea of sleep and concentrated more on survival. Finally he broke the silence. ‘What do you think?’

They instinctively knew what the other was thinking; they had been working together for two years and a special bond had been forged between them. They understood each other’s moods and fancies, knowing when something wasn’t quite right. When troubled Pete tended to lapse into long periods of silence, mulling things over and keeping them to himself, whereas Tony did the opposite and liked talking about any problems as he attempted to work them out.

‘Well, they certainly have done their homework. I was expecting a bloody big box with switches on.’

‘Considering how little time they had, they’ve worked miracles. It’s a pity there are no practice devices. I don’t like the idea of training with the same ones we are going to use on ops.’

‘The man said they’re indestructible, but he doesn’t know the lads. We could lose them, especially when parachuting, and there are no replacements.’

‘I think we only use them on the target attack phase, and not the infiltration.’

They discussed the best way to train with them, considering the alternatives. Tony tried to keep Peter engaged in conversation as he didn’t drive so fast when he was talking. When they lapsed into silence Pete would speed up and the scenery would flash by. They turned off the motorway onto a narrow country lane, and Tony was thrown around too much for his liking.

‘Do you remember them knock-out drops in Borneo?’ he asked.

Peter didn’t answer straight away as he came up fast behind a pick-up truck. He didn’t check his speed but accelerated past just as they were entering a left-hand bend. Tony’s foot stamped on an imaginary brake pedal with both hands gripping the dash, his eyes out on stalks scanning ahead. His worse nightmare happened: a car appeared, closing the distance rapidly. There was nowhere to go, thick hedges on both sides laced with large tree. A crash looked inevitable.

With less than inches to spare, Pete passed the truck and pulled back in, ignoring the fist waving and flashing lights from both vehicles.

‘No. What drops?’ he asked coolly.

Tony couldn’t speak – in fact he couldn’t remember the question – and when no answer came, Pete enquired, ‘Hungry, mate? Let’s stop at the dog stall for a sarnie.’

Tony stared intently at Peter, nursing the circulation back into his hands. The last thing he wanted at that moment was something to eat. When the crash seemed inevitable all he wanted to do as his last gesture on earth was to punch the driver as hard as he could. He was still fighting for composure. All of his ailments and discomforts had temporarily left him, but now they returned with a vengeance. His ears and lips throbbed, and a bout of cramp gripped his left calf. He thought to himself, ‘Wait till I get out he vehicle . . .’ but he actually said, ‘There’d better be a toilet handy.’

After a short break and all essentials had been catered for, they arrived at Shrivenham and went through the same routine as before. Security was more obvious here, but the same monotonous procedures were followed.

Eventually they were guided to a large hangar, where they were greeted by a lively, fit-looking man wearing a Royal Signals cap badge.

‘Hi, chaps. I’m Captain Charles Minter. Come on in. Please call me Chas. Toilets to the right, and my office is the last on the left, at the far end.’

He shook their hands warmly, pointing down a long bare brick corridor painted in a sickly green with polished brown lino covering the floor. There were many doors on the left-hand side, but only one large double door on the right. They followed the captain down the corridor, declining the offer of the toilet. All the doors were identical, varnished in dark oak with a frosted glass panel at the top. He stopped and opened the last but one door. Balancing on one leg, he stuck his head around the jamb and ordered, ‘Tea for three, Mary, and could you possibly round up some biscuits?’ Some things never change; the army thrives on its tea, and rarely goes an hour without a brew.

They went next door into the captain’s office, which looked more like a museum than a place of work. It was well lit, with two large windows giving a view over open fields. Each had a pair of cheap printed curtains hanging forlornly from large brass hooks, many of which were missing. The floral design was faded, giving the curtains the look of badly stowed sails on a battered yacht. Above one window was a line of regimental plaques, adding a splash of colour. The other two walls were smothered in photos and maps. In places they overlapped, making it hard to see the lime-green emulsion underneath. The grey filing cabinets were smothered in stickers from all the three services. Different squadrons, ships and regiments were represented. One sticker in particular caught Tony’s eye: ‘Paratroopers never die, they just go to hell and regroup.’ Even the desk was covered in militaria, and a conducted tour was needed to explain the models, badges and assortment of ammunition that lay there. Under a layer of transparent plastic were more photographs, and heaped at the back a pile of bayonets and knives. Not even the telephone or the wastepaper basket had escaped from the stickers, and when the tea was brought in by a middle-aged lady, wearing a brown tweed skirt and blue woollen twinset, the cups bore RAF squadron logos.

‘Thank you, Mary. If you set it down over there.’ Chas dropped a pile of maps on the floor to make room for the laden tray on top of a bookcase crammed untidily with books and magazines.

Pete and Tony were looking around the office, thinking they had seen everything, then something else would catch their eye. Chas removed a climbing rope from one chair and a pile of pamphlets from another. He gave the inquisitive pair a few more minutes, then invited them to sit down.

‘I think we have a mutual friend: Jimmy Thompson,’ suggested Chas.

‘Yeah, that’s right. Jimmy’s running Ops Research. He was going to come with us but got called away last night. I’m Tony Watkins, and this is Peter Grey. We are both in 2 Troop and have just came from the Fort.’

They exchanged pleasantries over the tea, and Chas was only too pleased to explain a lot of the paraphernalia that littered his office.

‘This round here never went into production; it was too expensive. This blunt-nose shell came from Iran and can penetrate . . .’ He went on for a good twenty minutes, holding the pair’s undivided attention. Although they were fascinated, however, they were on a tight schedule, and Tony had to take an exaggerated look at his watch to break the spell and get Chas back to the reason for their visit.

Carefully resheathing a bayonet, he laid it back on his desk. ‘That’s enough of my toys. Let me fill you in on yours. I don’t know how much of the background you are aware of, so stop me if you’ve heard it already.’ He made himself more comfortable before continuing.

‘Your Director was asked by the War Office to come up with a plan to protect the Task Force from air attack. He requested our assistance four weeks ago, regarding the menace posed by Exocets. These have been responsible for sinking three of our ships already. Working closely with RARDE, where you have just come from, we had to come up with a solution for stopping these air attacks on our fleet. If we don’t succeed we won’t have a Task Force left. We cannot afford to lose any more ships; this would seriously endanger our invasion plans. Argentina have some very useful pilots and in the Super Etendards a first-class aircraft.’ He paused while he went to the bookcase and selected a large book before settling back in his seat.

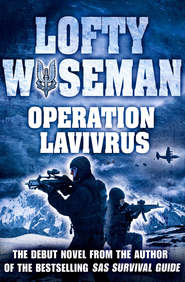

‘It’s not just a matter of you chaps going in and blowing the aircraft up. It’s got to be more subtle than that.’ He looked at the pair intently. ‘Because of the fragile coalition with neighbouring countries any assault on the mainland would be taken as an escalation of the war, and we would lose their support. So we have come up with “Operation Lavivrus”.’

He opened the large book on his lap, entitled Jane’s Aircraft Guide, and selected a double-paged pull-out picture of an aircraft that looked menacing even on paper. ‘This, lads, is the Super Etendard. Are you familiar with this aircraft?’

‘I know it’s French and I’ve seen one at Farnborough,’ replied Tony, ‘but that’s all.’ Peter merely nodded and studied the picture before him.

‘Yes, it’s a French strike fighter made by Dassault-Breguet. It’s an old design, but modified extensively. They have a carrier-borne capability, but so far have all been based ashore. It has a new wing, fitted with double slotted flaps, with a drooping leading edge. This is mounted in the mid-fuselage position and swept back at 45 degrees. The tricycle undercarriage is uprated with long-travel shock absorbers for carrier operations.’ All this was reeled off without a glance at the book or reference to any notes. The captain was full of nervous energy and was in his element. ‘The nose wheel is of special importance to you, and we will look at one in the hangar later. The new Atar 9k50 turbojet gives this aircraft an impressive performance: 733 m.p.h. at sea level, 45,000 feet ceiling and a operational combat radius of 528 miles.’

He propped the book open on the desk and used an old whip antenna as a pointer. He indicated different components as he introduced them, tapping the book for emphasis when required. His enthusiasm was infectious, holding the pair’s attention.

‘The armoured cockpit is pressurised and fitted with a Martin Baker lightweight ejection seat. They are all single-seaters, and this is a weak point. With all the sophistication of electronic counter-measures, inertial navigation and weapon systems, it puts too much strain on one man. A second man is desirable. The fuselage is an all-metal semi-monocoque construction, with integral stiffeners. The wings are attached by a two-bar torsion box covered by machined panels.’ A thin bead of sweat formed on his brow, but nothing slowed him down. ‘Now all aircraft are vulnerable on the ground, and you know more about this than I do, but there are several options that we looked at. Considerable damage can be done with a hammer, but this takes too long and is noisy. Obviously explosive does a complete job; it destroys the aircraft, and a timed delay allows the intruders to escape. But what we are trying to achieve has never been done before. We are going to mess with their weapon-aiming systems without the Argies knowing.’ Chas paused to gauge the reaction from his audience.

Tony reflected back to the day he was summoned with Peter into the Ops Room in Hereford and told of the planned incursion onto Argentinian soil. The aim was to neutralise the air threat to the Task Force. The whole operation had to be deniable, which was a contradiction in terms: How could you destroy the threat without leaving any evidence?

The plan was to attack the Super Etendards at their base, not with explosives but with an electronic gadget. To a soldier this was hard to comprehend; he likes to see a mass of burning metal, knowing his job is successful. To infiltrate and leave a device that still allows the aircraft to fly was against his instinct. These electronic devices were untried and involved all the dangers of placement but without the guarantee of success. If they didn’t work there was no second chance.

The operation had to be completely deniable as the British Government would be politically embarrassed by such a venture, and the world would see it as an escalation of the conflict. America had warned of the severe consequences of an invasion of the mainland. Countries sympathetic to Argentina, and those on the fence, could well join the war against Britain.

Captain Minter closed the book and offered them a cigarette. ‘Smoke, anyone?’ he said, offering them a packet of Capstan Full Strength. They both declined, deep in thought as they appreciated what a complicated mission they were engaged in. ‘I didn’t think you would. I’m trying to give up myself,’ he said, flicking open a Zippo lighter with a Special Forces logo on the sides; with a deft flick of the wrist he produced a two-inch flame and lit his cigarette. The resulting clouds of smoke brought the room alive. His desk now took on the look of a battlefield. Tony became agitated and backed away from the smoke, and Chas made a circular motion of his arm, trying to dissipate it.

‘We’ll go in the hangar shortly. It’s a non-smoking zone.’ This was his last chance of a puff, and he was taking full advantage of it. ‘Is there anything I’ve missed?’ he asked, tapping ash into an ashtray made from an artillery shell.

Tony coughed politely into a balled fist and asked, ‘What are the chances of getting away with it? Won’t they get suspicious if they keep missing and find the device?’

Chas answered through a curtain of smoke, exhaling forcefully. ‘Good point, Tony, but the clever thing about the placement is that on the ground it is nowhere near the weapons guidance system. You will see shortly how well it fits in position, and unless they have to service the nose wheel assembly it will go unnoticed. As for the missiles going astray, they will probably think we have developed a new counter-electronic measure. The device is completely passive until activated by the aircraft; it’s not switched on till the aircraft switches on its target acquisition radar.’

He opened up the book again to display the aircraft pull-out, and pointed. ‘The device is planted here on the nose wheel, and it’s only when the undercarriage is retracted that it comes in close proximity to the guidance system. They can only check the aircraft on the ground, so I think we have an excellent chance of getting away with it.’

They both pored over the diagram, noticing the position of the bay that held the electronics of the missile guidance system. It was directly above the recess where the nose wheel was stowed when retracted.

‘You put it in the right place and we will do the rest,’ added Chas between puffs on a rapidly diminishing cig.

‘What about the missile itself?’ enquired Peter. ‘Do we do anything to it?’

‘We have an Exocet in the hangar to show you, and our man, Mr Ford, will brief you on this. He is not available till three, so we will look at the undercarriage first. But in answer to your question, no, you don’t touch anything else. Just place the device in the correct position, and everything else is history,’ he said dramatically, stubbing out the remains of his cigarette. ‘Follow me, gents, and let’s see what we’ve got.’

They retraced their steps down the corridor and went through the large pair of double doors into the hangar. It was a massive structure illuminated by endless rows of fluorescent lights hanging down on chains from the cross-girders that supported the steeply angled roof. The walls were of red brick, giving way to corrugated sheeting at ceiling height, with a pair of huge sliding doors at the far end. The sheeting was painted in a fresh green colour, giving the vast area a pleasant, light atmosphere. The floor was painted red, and in neat rows, as far as the eyes could see, were mortars, artillery pieces, missiles and tanks.

Not many people were allowed in this hangar, and Tony thought the public would love to see this display. It was the best in the country, indeed probably in Europe.

‘This is superb,’ commented Peter. ‘Who uses this lot?’

Chas was leading them to the right between a row of mortars and tanks. He stopped by a multi-barrelled mortar, resting with his left leg up on the base plate with both arms folded over the sights bracket.

‘Basically we study weapon systems here. We obtain weapons and equipment from all around the world and evaluate it. We strip it down, test it and fire it. Most of this kit here is Warsaw Pact, but we look at everything. Anything new, we procure and test.’ Tony and Peter could detect the satisfaction that Peter got from his job, and were impressed by his enthusiasm and knowledge. They felt like rats in a cheese factory.

‘Officers study here for their degrees. They have to write a thesis on a particular subject. Also a lot of research is carried out here and improvements are made to existing equipment. This mortar is interesting. We just acquired it from Afghanistan. It’s the only one outside of the Soviet Bloc. I think some of your chaps were involved with its procurement.’

‘What will you do with it?’ enquired Pete.

‘We will strip it down, look at the workmanship and design, then we will take it on the range and check it for accuracy, range, penetration and all that sort of thing. Then back to the workshop and strip it down again, testing for wear and strength, and also durability’.

‘Sounds interesting,’ enthused Tony. ‘I would like a job like that myself.’

‘There you go, Tony. Get a commission, sit for a degree, and you can,’ mocked Peter.

Tony went red, his anger mounting. ‘I don’t like it that much, Pete. Somebody’s got to look after you.’ This was said with venom, prompting Peter to quickly change the subject. ‘What’s that over there?’ he said, pointing to a large artillery piece.

They moved on, slowly making their way to the side wall where the front section of an aircraft was positioned. The nose of the aircraft as far back as the cockpit was mounted like a game trophy coming out of the wall. The sleek shape painted blue-grey was complete with nose wheel assembly, refuelling probe, pitot tubes and tacan navigation system.

‘Believe it or not,’ said Chas, ‘this whole assembly retracts up into that hole, and these flaps seal it. Remarkable engineering, eh?’ He was gripping the landing gear and pointing to the dark aperture above it. ‘This is it, gents, courtesy of Messier-Hispano-Bugatti. Have a close look; it must be imprinted in your brain.’

The nose gear consisted of a large tube of bright alloy, with a smaller tube of steel emerging from the bottom connected to two wishbones. A large squashy tyre was pinned between these, and four struts braced the large tube on all sides, disappearing up into the aperture. About two-thirds down the main tube were two smaller alloy cylinders that ran back at an angle, filled with hydraulic fluid. These activated the gear, and alongside these were two steering levers, each made of bright alloy.

‘Do you notice anything familiar on the gear?’ asked Chas. The two crouched and stretched, examining the assembly minutely.

Chas put his hand on the hydraulic cylinder where the steering arm was connected. ‘Have a close look here.’ From either side the two stooped for a better look at where Chas was pointing. Lying snug between the two was a third aluminium cylinder twelve inches long and two inches in diameter.

‘That gentlemen is our device. Try and remove it.’