Полная версия:

A Small Death in Lisbon

ROBERT WILSON

A Small Deathin Lisbon

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1999

Copyright © Robert Wilson 1999

Robert Wilson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007322152

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007378142

Version: 2014-09-24

Dedication

For Janeandmy mother

Note

Although this novel is based on historical fact the story itself is complete fiction. All the characters and events are entirely fictitious and no resemblance is intended to any event or to any real person, either living or dead.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Note

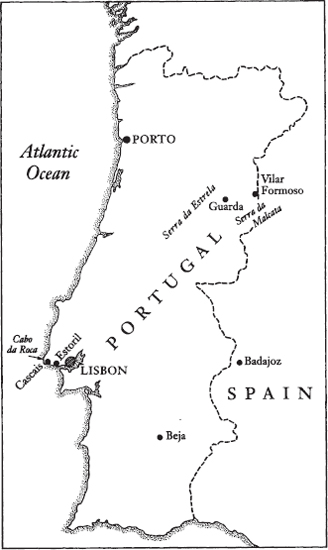

Map

Prologue

Part One

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Part Two

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

Chapter XXXII

Chapter XXXIII

Chapter XXXIV

Chapter XXXV

Chapter XXXVI

Chapter XXXVII

Chapter XXXVIII

Chapter XXXIX

Chapter XL

Chapter XLI

Chapter XLII

Chapter XLIII

Chapter XLIV

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map

Prologue

She was lying on a crust of pine needles, looking at the sun through the branches, beyond the splayed cones, through the nodding fronds. Yes, yes, yes. She was thinking of another time, another place when she’d had the smell of pine in her head, the sharpness of resin in her nostrils. There’d been sand underfoot and the sea somewhere over there, not far beyond the shell she’d held to her ear listening to the roar and thump of the waves. She was doing something she’d learned to do years ago. Forgetting. Wiping clean. Rewriting little paragraphs of personal history. Painting a different picture of the last half-hour, from the moment she’d turned and smiled to the question: ‘Can you tell me how . . .?’ It wasn’t easy, this forgetting business. No sooner had she forgotten one thing, rewritten it in her own hand, than along came something else that needed reworking. All this leading to the one thing that she didn’t like roaming loose around her head, that she was forgetting who she was. But this time, as soon as she’d thought the ugly thought, she knew that it was better for her to live in the present moment, to only move forward from the present in millimetre moments. ‘The pine needles are fossilizing in the backs of my thighs,’ was as far as she got in present moments. A light breeze reminded her that she’d lost her pants. Her breast hurt where it was trapped under her bra. A thought tugged at her. ‘He’ll come back. He’s seen it in my face. He’s seen it in my face that I know him.’ And she did know him but she couldn’t place him, couldn’t name him. She rolled on to her side and smiled at what sounded like breakfast cereal receiving milk. She knelt and gripped the rough bark of the pine tree with the blunt ends of her fingers, the nails bitten to the quick, one with a thin line of drying blood. She brushed the pine needles out of her straight blonde hair and heard the steps, the heavy steps. Boots on frosted grass? No. Move yourself. She couldn’t get the panic to move herself. She’d never been able to get the panic to move herself. A flash as fast as a yard of celluloid ripped through her head and she saw a little blonde girl sitting on the stairs, crying and peeing her pants because he’d chased her and she couldn’t stand to be chased. The rush. The gust of terrible energy. The wind up the stairs, whistling under the door. The forces winding up to deliver. Doors banging far off in the house. The thud. The thud of a watermelon dropped on tiles. Split skin. Pink flesh. Her blonde hair reddened. The cranial crack opened up. The bark bit a corner of her forehead. Her big blue eye saw into the black canyon.

Part One

Chapter I

15th February 1941, SS Barracks, Unter den Eichen, Berlin-Lichterfelde.

Even for this time of year night had come prematurely. The snow clouds, low and heavy as Zeppelins, had brought the orderlies into the mess early to put up the blackout. Not that it was needed. Just procedure. No bombers would come out in this weather. Nobody had been out since last Christmas.

An SS mess waiter in a white monkey jacket and black trousers put a tea tray down in front of the civilian, who didn’t look up from the newspaper he wasn’t reading. The waiter hung for a moment and then left with the orderlies. Outside the snowfall muffled the suburb to silence, its accumulating weight filled craters, mortared ruins, rendered roofs, smoothed muddied ruts and chalked in the black streets to a routine uniform whiteness.

The civilian poured himself a cup of tea, took a silver case out of his pocket and removed a white cigarette with black Turkish tobacco. He tapped the unfiltered end on the lid of the case, gothically engraved with the letters ‘KF’, and stuck the dry paper to his lower lip. He lit it with a silver lighter, engraved ‘EB’, a small and temporary theft. He raised the cup.

Tea, he thought. What had happened to strong black coffee?

The tight-packed cigarette crackled as he drew on it, needing to feel the blood prickling in his veins. He brushed two white specks of ash off his new black suit. The weight of the material and the precision of the Jewish tailoring reminded him just why he wasn’t enjoying himself so much any more. At thirty-two years old he was a successful businessman making more money than he’d ever imagined. Now something had come along to ensure that he would stop making money. The SS.

These were people he could not brush off. These people were the reason he was busy, the reason his factory – Neukölln Kupplungs Unternehmen, manufacturer of rail-car couplings – was working to full capacity, and the reason why he’d had an architect draw up expansion plans. He was a Förderndes Mitglied, a sponsoring member of the SS, which meant he had the pleasure of taking men in dark uniforms for nights out on the town and they made sure he got work. None of this was in the same league as being a Freunde der Reichsführer-SS, but it had its business advantages and, as he was now seeing, its responsibilities as well.

He’d been living with the institutional smells of boiled cabbage and polish in the Lichterfelde barracks for two days, snarled up in their military world of Oberführers, Brigadeführers, and Gruppenführers. Who were all these people in their Death’s Head uniforms, with their endless questions? What did they do all day when they weren’t scrutinizing his grandparents and great-grandparents? We’re at war with the whole world and all they need is your family tree.

He wasn’t the only candidate. There were other businessmen, one he recognized. They all worked with metal. He had hoped they were being sized up for a tender, but the questions had been strictly non-technical, all character assessment, which meant they wanted him for a job.

An assistant, or adjutant or whatever these people called themselves came in. The man closed the door behind him with librarian care. The precise click and satisfied nod started the irritation winding up inside him.

‘Herr Felsen,’ said the adjutant sitting down in front of the wide, hunched shoulders of the dark-haired civilian.

Klaus Felsen shook his stiff foot and raised his hefty Swabian head and gave the man a slow blink of his blue-grey eyes from under the ridged bluff of his forehead.

‘It’s snowing,’ said Felsen.

The adjutant, who found it difficult to believe that the SS had been reduced to considering this . . . this . . . some ruthless peasant with an unaccountable flair for languages, as a serious candidate for the job, ignored him.

‘It’s going well for you, Herr Felsen,’ he said, cleaning his glasses.

‘Oh, you’ve had some news from my factory?’

‘Not exactly. Of course, you’re concerned . . .’

‘Everything’s going well for you, you mean, I’m losing money.’

A nervous look from the adjutant fluttered over Felsen’s head like a virgin’s petticoat.

‘Do you play cards, Herr Felsen?’ he asked.

‘My answer’s the same as the last time – everything except bridge.’

‘There’ll be a card game here in the mess tonight with some high-ranking SS officers.’

‘I get to play poker with Himmler? Interesting.’

‘SS-Gruppenführer Lehrer in fact.’

Felsen shrugged; he didn’t know the name.

‘Is that it? Lehrer and me?’

‘And SS-Brigadeführers Hanke, Fischer and Wolff who you’ve already met, and another candidate. It’s just an opportunity for you . . . for them to get to know you in a more relaxed way.’

‘Poker’s not considered degenerate yet?’

‘SS-Gruppenführer Lehrer is an accomplished player. I think it . . .’

‘I don’t want to hear this.’

‘I think it would be advisable for you to . . . ah . . . lose.’

‘Ah . . . more money?’

‘You’ll get it back.’

‘I’m on expenses?’

‘Not quite . . . but you will get it back in another way.’

‘Poker,’ said Felsen, wondering how relaxed this game would be.

‘It’s a very international game,’ said the adjutant getting up from the table. ‘Seven o’clock then. Here. Black tie for you, I think.’

Eva Brücke sat in the small study of her second-floor apartment on Kurfürstenstrasse in central Berlin. She was at her desk wearing just a slip under a heavy black silk dressing gown with gold dragon motifs and a woollen blanket over her knees. She was smoking, playing with a box of matches and thinking of the new poster that had appeared on the billboard of her apartment building. It said ‘German women, your leader and your country trust you.’ She was thinking how nervous and unconfident that sounded – the Nazis, or maybe just Goebbels, subconsciously revealing a deep fear of the unquantifiable mystery of the fairer sex.

Her brain slid away from propaganda and on to the nightclub she owned on the Kurfürstendamm, Die Rote Katze. Her business had boomed in the last two years for no other reason than she knew what men liked. She could look at a girl and see the little triggers that would set men off. They weren’t always beautiful, her girls, but they’d have some quality like big blue innocent eyes, or a narrow, long, vulnerable back, or a shy little mouth which would combine perversely with their total availability, their readiness to do anything that these men might think up.

Eva’s shoulders tightened and she pulled the blanket off the back of the chair around her. She’d begun to feel dizzy because she’d been smoking too fast, so fast that the end of her cigarette was a long, thin, sharp cone. This only happened when she was irritated, and thinking about men irritated her. Men always presented her with problems, and never relieved her of any. Their job, it appeared, was to complicate. Take her own lover. Why couldn’t he do what he was supposed to do and just love her? Why did he have to own her, intrude on her, occupy her territory? Why did he have to take things? She chucked the matches across the desk. He was a businessman, and that, she supposed, was what businessmen did for a living – accumulated things.

She tried to get her mind off men, especially her clients and their visits to her office at the back of the club where they’d sit and smoke and drink and charm until they’d get to what they really wanted which was something special, something really special. She should have been a doctor, one of those new-fangled brain doctors who talked you out of your madness, because as the war had worn on she’d noticed the tastes of her clients had changed. Normally, these days, as she’d found out to her cost, to include pain – both inflicting it and, perhaps to redress the balance, receiving it. And then there was one man who’d come and asked of her something that even she didn’t know whether she’d be able to supply. He was such a quiet, insignificant, enclosed man, you wouldn’t have thought . . .

There was a knock at the door. She crushed her cigarette, threw off the blankets and tried to plump some life into her blonde hair but lost heart when she caught sight of herself in the mirror with no make-up. She refolded the dressing gown across herself, pulled the belt tight and went to open the door.

‘Klaus,’ she said, producing a smile. ‘I wasn’t expecting you.’

Felsen pulled her over the threshold and kissed her hard on the mouth, desperate after two days in the barracks. His hand slid down to her lower back. Her fists came up and she pushed herself away from his chest.

‘You’re wet,’ she said, ‘and I’ve only just woken up.’

‘So?’

She went back inside and hung up his hat and coat and led him back to her study. He followed with his slight limp. She never used the living room, she preferred small rooms.

‘Coffee?’ she asked, drifting over to the kitchen.

‘I was thinking . . .’

‘The real thing. And brandy?’

He shrugged and went into the study. He sat on the client side of the desk, lit a cigarette and picked the flakes of tobacco off his tongue. Eva came in with the coffee, two cups, a bottle and glasses. She stole one of his cigarettes which he lit for her.

‘I was wondering where that was,’ she said, tugging the lighter out of his grip, annoyed.

She was wearing lipstick now and had brushed her hair. She pulled the telephone plug out of the wall, so that they could talk privately.

‘Where’ve you been?’ she asked.

‘Busy.’

‘Trouble at the works?’

‘I’d have preferred that.’

She poured the coffee and tipped some brandy into hers. Felsen stopped her doing the same to his.

‘After,’ he said. ‘I want to enjoy the coffee. They’ve been making me drink tea for two days.’

‘Who’s they?’

‘The SS.’

‘They’re so brutal those boys,’ she said, irony on automatic, unsmiling. ‘What do the SS want from a sweet little Swabian peasant like you?’

The smoke curled under the art deco lamp. Felsen tilted the shade downwards.

‘They’re not saying, but it feels like a job.’

‘Lots of questions about your pedigree?’

‘I told them my father ploughed the strong German soil with his bare hands. They liked it.’

‘Did you tell them about your foot?’

‘I said my father dropped a plough on it.’

‘Did they laugh?’

‘It’s not a very humorous atmosphere down there.’

He finished his coffee and poured brandy over the dregs.

‘Do you know someone called Gruppenführer Lehrer?’ asked Felsen.

‘SS-Gruppenführer Oswald Lehrer,’ she said, becoming very still. ‘Why?’

‘I’m playing cards with him tonight.’

‘I’ve heard he’s in charge of running the SS or rather the KZs as a business . . . making them pay for themselves. Something like that.’

‘You know everybody, don’t you?’

‘That’s my business,’ she said. ‘I’m surprised you haven’t heard of him. He’s been in the club. This one and the old one.’

‘I have. Of course I have,’ he said, but he hadn’t.

Felsen’s mind raced. KZs. KZs. What did that mean? Were they going to assign him some cheap concentration camp labour? Switch his factory over to munitions production? No. Job. It was for a job. He felt the cold in his bones suddenly. They weren’t going to make him run a KZ, were they?

‘Drink some brandy,’ said Eva, sitting on his lap. ‘Stop guessing. You’ve got no idea.’

She ran her fingers over his bristly head and thumbed one of his cheekbones as if he was a child with a mark. She tilted his head and planted some fresh lipstick on his mouth.

‘Stop thinking,’ she said.

He slipped a large hand up under her armpit and cupped one of her firm, braless breasts. He eased another hand under the hemline of the slip. She felt him hardening under her. She stood, wrapped herself in the gown again and knotted the belt. She leaned in the doorway.

‘Am I seeing you tonight?’

‘If they let me go,’ he said, shifting in his seat, his erection troubling him.

‘Didn’t they ask how come a Swabian farmboy speaks so many languages?’

‘Yes, they did, as a matter of fact.’

‘And you had to give them a guided tour of all your lovers.’

‘Something like that.’

‘French from Michelle.’

‘That was French was it?’

‘Portuguese from that Brazilian girl. What was her name?’

‘Susana. Susana Lopes,’ he said. ‘What happened to her?’

‘She had friends. They got her out to Portugal. She wouldn’t have lasted long in Berlin with that dark skin,’ said Eva. ‘And Sally Parker. Sally taught you English, didn’t she?’

‘And poker and how to swing.’

‘Who was the Russian?’ asked Eva.

‘I don’t speak Russian.’

‘Olga?’

‘We only got as far as da.’

‘Yes,’ said Eva, ‘niet wasn’t in her vocabulary.’

They laughed. Eva leaned over him and tilted the lampshade back up.

‘I’ve been too successful,’ said Felsen, failing to look sorry for himself, trickling more brandy into his cup.

‘With women?’

‘No, no. Drawing attention to myself . . . all this entertaining I do.’

‘We’ve had some good times,’ said Eva.

Felsen stared into the carpet.

‘What did you say?’ he asked suddenly, looking up at her, surprised.

‘Nothing,’ she said, leaning over him to stub her cigarette out. He breathed her in. She stepped back. ‘What are you playing tonight?’

‘Sally Parker’s game. Poker.’

‘Where are you taking me with your winnings?’

‘I’ve been advised to lose.’

‘To show your gratitude.’

‘For a job I don’t want.’

Outside a car drifted through the slush down Kurfürstenstrasse.

‘There is one possibility,’ she said.

Felsen looked up, sun perhaps breaking through the cloud.

‘You could clean them out.’

‘I’ve thought of it,’ he said, laughing.

‘It could be dangerous but . . .’ she shrugged.

‘They wouldn’t stick me in a KZ, not with what I’m doing for them.’

‘They stick anybody in a KZ these days . . . believe me,’ she said. ‘These are the people who cut down the lime trees on Unter den Linden so that when we go to the Café Kranzler all we have are those eagles on pillars looking down on us. Unter den Augen they should call it. If they can do that they can stick Klaus Felsen, Eva Brücke and Prince Otto von Bismarck in a KZ.’

‘If he was still alive.’

‘What do they care?’

He stood and faced her, only a few inches taller but nearly three times wider. She put a slim white arm, the wrist a terminus of blue veins, across the door.

Take the advice you’ve been given,’ she said. ‘I was only joking.’

He grabbed at her, his fingers slipping into the crack of her bottom which she did not like. He went to kiss her. She twisted and yanked his hand away from behind her. They manoeuvred around each other so that he could get himself out of the door.

‘I’ll be back,’ he said, without meaning it to sound a threat.

‘I’ll come to your apartment when I’ve closed the club.’

‘It’ll be late. You know what poker’s like.’

‘Wake me if I’m sleeping.’

He opened the door to the apartment and looked back down the corridor at her. Her dressing gown had been rucked open. Her knees, below the hem of her slip, looked tired. She seemed older than her thirty-five years. He closed the door, trotted down the stairs. At the bottom he rested his hand on the curl of the bannister and, in the weak light of the stairwell, had the sense of moorings being loosed.

At a little after six o’clock Felsen was standing in his darkened flat looking out into the matt black of the Nürnbergerstrasse, smoking a cigarette behind his hand, listening to the wind and the sleet rattling the windowpane. A slit-eyed car came down the road, churning slush from its wheel-arches, but it wasn’t a staff car and it continued past him into the Hohenzollerndamm.

He smoked intensely thinking about Eva, how awkward that had been, how she’d needled him bringing up all his old girlfriends, the ones before the war who’d taught him how not to be a farmboy. Eva had introduced him to all of them and then, after the British declared war, moved in herself. He couldn’t remember how that had happened. All he could think of was how Eva had taught him nothing, tried to teach him the mystery of nothing, the intricacies of space between words and lines. She was a great withholder.

He pieced their affair back to a moment where, in a fit of frustration at her remoteness, he’d accused her of acting the ‘mysterious woman’, when all she did was front a brothel as a nightclub. She’d iced over and said she didn’t play at being anything. They’d split for a week and he’d gone whoring with nameless girls from the Friedrichstrasse, knowing she’d hear about it. She ignored his reappearance at the club and then wouldn’t have him back in her bed until she was sure that he was clean, but . . . she had let him back.