Полная версия:

A Darkening Stain

A Darkening Stain

Robert Wilson

For Jane

and

my sister, Anita

The sky is darkening like a stain; Something is going to fall like rain, And it won’t be flowers.

‘The Witnesses’ (W. H. Auden)

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

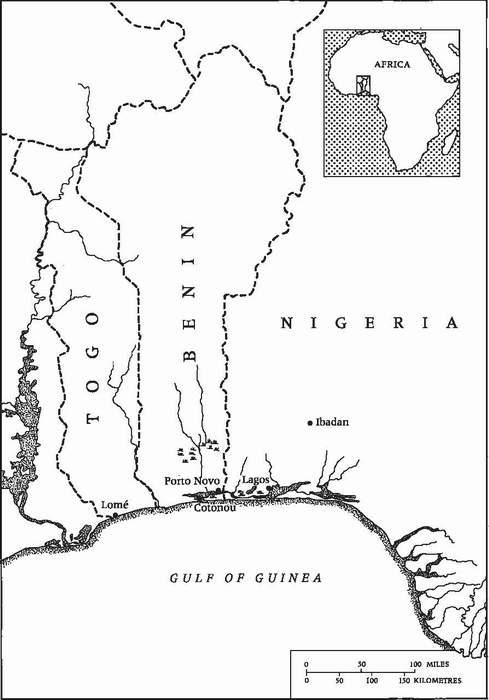

Map

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

1

Friday 19th July, Cotonou Port.

The thirty-five-ton Titan truck hissed and rocked on its suspension as it came to a halt. Shoulders hunched, it gave a dead-eyed stare over the line of scrimmage which was the chain across the opening of the port gates. On the wood panelling behind the cab were two hand-painted film posters of big men holding guns – Chuck Norris, Sly Stallone – the bandana boys. He handed down his papers to the customs officer who took them into the gatehouse and checked them off. Excitement rippled through the rollicking crowd of whippet-thin men and boys who’d gathered outside the gates in the afternoon’s trampling heat, which stank of the sea and diesel and rank sweat.

The Titan was loaded with bales of second-hand clothes tied down on to the flat-bed of the truck by inch-thick hemp rope. The driver, faceless behind his visor, kicked up the engine which blatted black fumes from a four-inch-wide pipe, ballooning a passing policeman’s shirt. A squeal of anticipation shimmered through the crowd.

Six men, armed with wooden batons the thickness of pickaxe handles, climbed on to the edges of the flat-bed, three a side. Each of them twisted a wrist around a rope and hung off, twitching their cudgels through the thick air. The crowd positioned themselves along the thirty metres of road from the gates to the junction with Boulevard de la Marina. The officer came out with the papers and handed them back up to the driver. He nodded to the man on chain duty who looked at the crowd outside and grinned.

The huge truck farted up some more and lurched as the driver thumped it into gear. He taunted the crowd with his air brakes. They giggled, high-pitched, nearly mad. The chain dropped and the battered, grinning face of the Titan dipped and surged across the line. The men hanging off the back roared and slashed with their batons. The truck picked up some momentum, the cab through the gates now, and the crowd threw themselves at the wall of bales, clawing at the clothes packed tight as scrap metal. The batons connected. Men and boys fell stunned as insects, one was dragged along by the leg of a pair of jeans he’d torn from a bale until a sharp crack on the wrist dropped him. The Titan snarled into second gear.

I saw the boy coming from some way off. He was dressed in a white shirt, a pair of long white shorts and flip-flops. He turned the corner off Boulevard de la Marina up to the port gates and was swallowed up by the mêlée who were now running at a sprint. A baton arced down into the pack and caught the boy on the back of the head. He fell forward, bounced off the hip of some muscled brute who held the reins of a nylon pink nightie stretched to nine feet, and disappeared under the wheels of the Titan.

The crowd roared, and the section around where the boy had fallen collapsed to the ground. The truck pulled away, crashing through the gears. It didn’t stop for the Boulevard de la Marina. The driver stood on his horn. Cars and mopeds squirmed across the tarmac. The men riding shotgun stopped swinging their batons and hung on with both hands. The Titan let out a final triumphant blat of exhaust and headed into town.

I got out of my Peugeot and ran across to where the boy had gone down. People came from all angles. Closer, I could see his arm, the white bone of his arm and the blood soaking into the sleeve and up the chest of his shirt. Some of the hoodlums around him were smeared with his blood, four of them upped and ran. The rest were staring down at the mash of flesh and bone and the thick red ooze on the road. Then the boy was picked up and borne away, his crushed arm hanging like a rag, his head thrown back, eyes rolled to white. Three men ran him down to the main road and threw him into a car which took off in the direction of the hospital. Then they stood and looked at his blood on their shirts.

I was called back to my car which was waiting to get into the port. Horns blared. Arms whirled.

‘M. Medway, M. Medway. Entrez, entrez! Main-te-nant. Main-te-nant.’

I drove in, threading through the line of trucks waiting to get out, past a pile of spaghetti steel wire just beginning to brown with rust. It was five o’clock in the afternoon. I took a small towel from the passenger seat and wiped away the tears of sweat streaming down my face.

I was heading for a ship called the Kluezbork II, Polish flag, 15,000 tons deadweight. Bagado, my ex-partner in M & B ‘Investigations and Debt Collection’ and now back in the Cotonou force in his old job as a detective, was waiting for me on board. He had a problem, a five-men-dead problem. But it wasn’t as big as the captain’s problem which was five men dead on his ship, all stowaways, his vessel and cargo impounded indefinitely and he passing the time of day right now in a hell cell with twenty odd scumbags down at the Sûreté in town.

Bagado had told me to get down to the port as fast as possible because the stink was getting bad and they wanted the bodies on ice pronto, but it was important for me to see the situation down there. Why me? He’d blethered on about my shipping experience, but what he really wanted to do was to talk and since his boss, Commandant Bondougou, had split us up and taken him back into the force he didn’t like being seen down at my office too much.

The ship’s holds were all open and I caught the smell of the five men beginning to putrefy from the quay. The engineer pointed me to number three hold’s hatch where some sick-looking young policemen were hanging around for further instructions. Bagado was waiting on a platform halfway down into the hold. He stood, hands jammed into the pockets of his blue mac, which had more creases than an old man’s scrotum. He nodded over the platform’s rail at the five dead men. Three of them were propped against the metal wall of the hold looking as if they’d just dozed off while staring at the wall of timber which was the cargo in hold number three. The other two lay on their fronts, in the metre or so in between, like tired children who’d dropped to the floor mid-play. It was a peaceful scene uncreased by violence.

‘What are you doing up here?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know what killed them yet,’ said Bagado, coming out of his trance, flat, depressed. ‘I don’t want to go down there and end up like that.’

‘How long’s the hold been open?’

‘Three or four hours.’

‘That should have got the air circulating. Let’s take a look.’

We climbed down the ladder on to the floor of the hold.

‘Looks as if they suffocated to me,’ said Bagado. ‘No violence, anyway.’

‘We’re a long way from the engine room,’ I said. ‘Who found them?’

‘The first mate was doing a routine stowaway check and didn’t like the smell in here…brought the master to the platform…that was it.’

‘The only time I’ve heard of people suffocating in holds is on tankers, especially after palm oil. Gives off a lot of carbon dioxide. They send in the cleaners and they get halfway down the ladder before they realize they can’t breathe. I heard of eight people dying like that in one hold up on Humberside.’

‘But this hold isn’t enclosed like a tanker’s,’ said Bagado, leaning against the timber wall.

‘Wouldn’t matter if the oxygen’s displaced from the bottom,’ I said, and walked between the bodies to the other side of the hold. Bagado pushed himself off the timber to follow me.

‘Damn,’ he said, looking at the shoulder of his mac, a big stain on it.

I touched the logs. They were still wet with sap.

‘This timber’s fresh,’ I said.

‘Loaded out of Ghana three nights ago.’

‘I’ve heard about some of these hardwoods. They give off fumes, some of them toxic. They’re pretty volatile in the heat. You put that in an enclosed hold, the oxygen levels drop…’

‘Cause of death – fresh timber,’ said Bagado. ‘Could be.’

‘Who are these guys?’ I asked. ‘They got any ID?’

‘They’re all Beninois.’

‘How’d they get on board?’

‘With the stevedores. They were loading cotton seed in holds one and two over the last couple of days. Four teams of them.’

‘You know that?’

‘A guess. We’re picking up the chef d’équipe now,’ he said.

‘What am I doing here, Bagado?’ I asked. ‘You didn’t get me down here to talk botany.’

Bagado shouted up to his juniors. A head appeared over the platform’s rail. He rattled instructions out using Fon rather than French. The head disappeared. Feet rang on the rungs of the ladder. Bagado turned back to me, a faint sneer on his face from the stink of the bodies and something else.

‘Let’s go up on to the platform,’ he said.

‘Was that guy listening in on you?’

‘As you can see,’ he said. ‘I do have a problem.’

We climbed back up on to the platform.

‘But not with these five,’ I said to the soles of his feet.

‘Bondougou,’ he said, the name mingling naturally with the rotten air. A name that brought tears of gratitude to the eyes of corrupt businessmen, politicians and civil servants. The name of the man who’d targeted Bagado’s life and set about dismantling it piece by piece. The first time Bagado and I met he’d just been sacked by Bondougou for issuing an unauthorized press release about a dead girl’s tortured body. He’d come to work with me after that, until our recent split, and those circumstances weren’t exactly lavender-scented either. Since then Bondougou had given Bagado investigations and pulled him on almost every one as soon as he started getting anywhere. The only people he got to put in the slammer were the ones who’d reined in on last year’s Christmas gift to the Commandant. Bondougou and Bagado were polar opposites. They needed each other only for metaphysical reference.

‘So, tell me,’ I said, once we were up on the platform.

‘He has to be…’ Bagado’s voice faded, as he leant over the rail.

‘Come again.’

‘He has to go.’

‘And you think I’m the man for the job or I’m the man who can find you the man to do the job?’

‘Be serious, Bruce.’

‘So, what does “he has to go” mean? I assume you’re talking about into the ground six foot under or stuffed head first down a storm drain after heavy rain. He’s not the kind to take early retirement just because he’s upset a few of his detectives.’

‘That would be a very satisfactory outcome. The storm drain I think is the more likely…but you know me, Bruce. It’s just not possible for me to even think like that.’

‘Whereas I…’

‘Quite.’

‘…go grasping the wrong end of the stick,’ I said. ‘We used to be partners, didn’t we, Bagado?’

‘And very complementary ones too, I thought.’

‘I don’t remember getting any compliments.’

‘I can’t think why,’ said Bagado, his neck disappearing into the collar of his mac.

‘So what’s Bondougou’s game? What’s he done to…?’

‘He’s gone too far,’ he said, to the dense knot of his dark tie.

‘Well, I thought he must have done more than scribble over your prep,’ I said, wiping a finger across my forehead and dropping a hank of sweat through the metal grating of the platform floor.

‘Five girls have gone missing…’

‘In Cotonou?’

‘Schoolgirls,’ he nodded. ‘The youngest is six, the eldest, ten.’

‘And he won’t let you near it?’

‘He’s put one of his resident idiots on it.’

‘Any bodies turned up?’

‘No.’

‘You think all five are connected?’

‘Things like that are always connected.’

‘Why do you think this is Bondougou’s business?’ I asked. ‘Just because he won’t let you near it, or what?’

‘He’s on it. He reads everything that comes in. Takes all the reports verbally first. He’s very interested.’

Bagado started to snick his thumbnail against his front teeth, a tic that meant he was thinking – thinking and worrying.

‘How am I supposed to fit myself in on this?’ I asked. ‘If Bondougou finds me sniffing around he’ll hit home runs with my kneecaps. And the usual usual – I’ve got a living to earn somehow.’

‘I know, I know,’ he said, and stared down into the hold at the five dead men. ‘How are we going to get these men out of here?’

‘Put them in a cargo net and lift them out.’

‘Let’s go,’ he said. ‘Before I get morbid.’

‘You mean you aren’t morbid yet?’

We climbed back up on to the hot metal deck and leant over the ship’s rail, gulping in air cut with bunker fuel and some muck they had boiling in the ship’s galley – whatever, it was fresh after all that. The full weight of the afternoon heat was backing off now, the sun tinting some colour back into things.

‘I want you to help me, Bruce.’

‘Any way I can, Bagado,’ I said. ‘As usual I’m running this way and that, feet not touching the ground.’

‘Who’s that for?’

‘Irony, Bagado. Don’t go losing your sense of irony.’

‘I’m losing my sense of everything these days…because there is no sense in anything. It’s all non-sense. How did I get to this pretty pass, Bruce?’

‘This pretty what?’

‘Pass.’

‘Is that one of your pre-independence colonial expressions?’

‘Concentrate for me, will you?’

‘OK. You’ve been manoeuvred into a position by Bondougou and now you’ve decided to manoeuvre your way out and I’m going to help you.’

‘How?’

‘You’ve only just saddled me with the problem. Let me run around a bit, break myself in on it.’

‘No hit men.’

‘I don’t know any hit men. How would I know any, Bagado? Just because I mix in that…’

‘Irony, Bruce. I was being ironical.’

2

I drove out of the port, the sky already turning in the bleak late afternoon. People were still standing over where the boy’s arm had been crushed, the stain darkening into the tarmac. I turned right on to the Boulevard de la Marina, heading downtown. Bagado had told me to keep my mouth shut about the stowaways and the fresh timber theory. If he wanted to land the marlin instead of the minnows he needed some tension to build up on the outside and the best way was to let the rumour machine run amok.

The traffic was heavy in the centre of town, with the going-home crowd heading east over the Ancien Pont across the lagoon. The long rains had been going on too long and the newly laid tarmac for last year’s Francophonie conference was getting properly torn up. Cars eased themselves into crater-like potholes. Bald truck tyres chewed off more edges as they ground up out of the two-foot trenches that had only been a foot deep the week before.

Night fell at the traffic lights in central Cotonou. Beggars and hawkers worked the cars. Mothballs, televisions, dusters, microwaves. I didn’t do too much thinking about Bagado’s problem. Disappearing schoolgirls was not my business and the only way Bondougou was leaving was if he overplayed a hand against somebody a lot nastier than I and they gave him the big cure. That might happen…eventually. But me? I’d rather steer clear of that stuff. Make some money. Keep my head down. Things were going better than usual. I had money in my pocket and Heike, my English/German girlfriend, and I were getting along with just the odd verbal, no fisticuffs. I got a surge just thinking about her and not only from my loins.

A calloused hand, grey with road dust, appeared on my windowsill. It belonged to one of the polio beggars I supported at what they called ‘my traffic lights’.

‘Bonjour, ça va bien?’ he asked, arranging his buckled and withered limbs underneath him.

‘ça marche un peu,’ I said, wiping my face off. I gave him a couple of hundred CFA.

‘Tu vas réussir. Tu vas voir. Tu vas gagner un climatiseur pour ta voiture.’

Yes, well, that would be nice. These boys understand suffering. I could do with some cool. I could do with an ice-cold La Beninoise beer. I parked up at the office, walked back to the Leader Price supermarket and bought a can of cold beer. I crossed the street to the kebab man, standing in front of his charcoal-filled rusted oil drum, and had him make me up a sandwich of spice-hammered meat, which he wrapped in newspaper.

The gardien at the office said I had visitors. White men. I asked him where he’d put them and he said he’d let them in. He said that they’d said it would be all right.

Did they?

I went up, thinking there was nothing to steal, no files to rifle, no photos to finger through, only back copies of Container Week and such, so maybe I’d find a couple of guys eager to see someone to brighten the place up and keen to part with money just to get out of the place.

Sitting on my side of the desk, just outside the cone of light shed from a battered Anglepoise, was a man I recognized as Carlo, and on the client side a guy I only knew by sight. Suddenly my lamb kebab didn’t taste so good. These two were Franconelli’s men. Roberto Franconelli was a mafia capo who operated out of Lagos picking up construction projects and Christ knows what else besides. We’d started our relationship by hitting it off and then I’d made a mistake, told a little fib about a girl called Selina Aguia, said she was interested in him when she wasn’t (not for that reason, anyway). Now Mr Franconelli had a healthy, burgeoning dislike for my person and I knew that this little visit was not social.

‘Bruce,’ said Carlo, holding out his hand. I juggled the beer and kebab and he slapped his dark-haired paw into mine. ‘This is Gio.’

Gio didn’t take the heel of his hand away from his face and gave me one of those minimalist greetings I associate with coconuts.

Carlo sat back out of the light and put his feet up on my desk, telling me something I didn’t need to be told.

‘I’d offer you a beer…’ I said.

‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘Gio?’

Gio didn’t move an eyelid.

‘He’ll have a Coke. He don’t drink.’

I slammed my can of beer down and slid it across to Carlo. I shouted for the gardien and gave him some money for another beer and a Coke. I took the third chair in the room and drew it up to the desk. Carlo nestled the beer in his lap and pinged the ring-pull, not breaking the seal. I continued with the lamb kebab and gave Gio a quick once-over. Brutal. Trog-brutal.

‘You eat that shit off the street?’ asked Carlo.

‘Keeps up my stomach flora, Carlo,’ I said. ‘I don’t want you to think I actually like it.’

Carlo said something in Italian. Gio wrinkled his nose. Animated, heady stuff.

‘You don’t mind if I smoke?’ asked Carlo. ‘While you do your stomach flora thing.’

‘I’m touched you asked.’

He lit up. The gardien came back with the drinks. Gio and I opened our cans.

‘Chin-chin,’ I said.

Carlo kept on pinging.

‘This a social?’ I asked, wiping my fingers off on the newspaper.

‘Mr Franconelli’s got a job for you.’

‘I didn’t think Mr Franconelli liked me any more.’

‘He don’t.’

‘Does that mean he won’t be paying?’

‘He’ll pay. You’re small change.’

‘What’s the job?’

‘Find someone,’ said Carlo, stretching himself to a shivering yawn.

‘You can tell me it all at once, you know, Carlo. I can take in more than one thing at a time – beer, kebab, your friend here, who you want me to find – all in one big rush.’

‘The guy’s name is Jean-Luc Marnier.’

‘Would that be a full-blooded Frenchman, a métis, or an African?’

Carlo flipped a photo across to me. Jean-Luc Marnier was white, in his fifties, with thick, swept-back grey hair that was longish at the collar and tonic-ed. It had gone yellow over one eye, stained by smoke from an unfiltered cigarette he had in his mouth. Attractive was just about an applicable adjective. He might have been movie-hunk material when he was younger and smoother, but some hardness in his life had cragged him up. He had prominent facial bones – cheeks, jaw, forehead all rugged with wear – a full-lipped mouth, surprisingly long ears with fleshy lobes and a blade-sharp nose – a seductive mixture of soft and hard. His dark eyes were shrewd and looked as if they could find weaknesses even when there weren’t any. I thought he probably had bad teeth, but he looked like a ladies’ man, which meant he’d have had them fixed. The man had some presence, even in a photo, but it was a rogue presence.

‘Is he a big guy?’ I asked.

‘A metre seventy-five. Eighty-five kilos. Not fat, just a little heavy.’

‘What’s he do?’

‘Import/export.’

‘For a change,’ I said. ‘He have an office?’

‘And a home,’ said Carlo, sliding over a piece of paper.

‘Why can’t you find him yourself?’

Carlo pinged the ring-pull some more, getting on my nerves.

‘We’ve looked. He’s not around. Nobody talks to us.’

‘Does that mean he’s been a bad boy?’

‘Take a look at the guy,’ said Carlo.

‘What do I do when I find him?’

Gio looked at Carlo out of the corner of his hand as if he might be interested in something for the first time.

‘You just tell us where he is.’

‘Then what?’

‘Finish,’ he said, and crushed his cigarette out in the tuna can supplied.

‘You going to kill him? Is that it?’

Carlo and Gio stilled to a religious quiet.

‘Forget it, Carlo,’ I said. ‘That is not my kind of work.’

Carlo’s feet crashed to the floor. He slammed the beer can down on the desk top and leaned over at me so that our faces were close enough for beer and tobacco fumes to be exchanged.

‘I thought you were the one who liked me, Carlo.’

‘I do, Bruce. I like you fine. But not when you’re dumb.’

‘Then I don’t know how you ever got to like me.’

Carlo grunted about one sixteenth of a laugh. He put his hand on my shoulder and gave me a little massage, brutally thumbing the muscle over the bone.

‘I know a lot of smart people who tell me they’re dumb.’

‘It’s a trick we learn,’ I said.

‘Now, Gio, you might be surprised to learn, is a very remarkable teacher ‘cos he can make dumb people think smart and smart people think dumb. Not bad for a guy who’s never been to school, still has trouble readin’ a book with no pictures.’