Полная версия:

Plume

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Will Wiles 2019

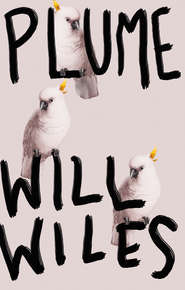

Cover design by Luke Bird

Cover illustration © Blue Jean Images / Alamy

Will Wiles asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears here.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008194413

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008194420

Version: 2019-03-25

Dedication

For my parents, with love.

Epigraph

‘People begin to see that something more goes into the composition of a fine murder than two blockheads to kill and be killed — a knife — a purse — and a dark lane. Design, gentlemen, grouping, light and shade, poetry, sentiment, are now deemed indispensable to attempts of this nature.’

‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’

Thomas De Quincey

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Will Wiles

About the Publisher

ONE

We want beginnings. We want strong, obvious beginnings. Start late, finish early, that’s the advice from people who write magazine features. Ditch the scene-setting, background-illustrating and throat-clearing and get stuck in. It’s not a novel.

Lately, however, I’ve been fixated on beginnings, and their impossibility. I trace back and back through my life, trying to find the day, the hour I started to fail. Whenever I alight upon a plausible incident, where it might make sense to begin, I find causes and reasons and conditions and patterns that can be traced back further. And then I discover that I have gone back too far, that I have reached a point well before the event horizon of my failure, where the mass of it in my future overcomes any possibility of escape in the present. No fatal slip, or fatal sip.

Start late, finish early. Start with a bang. Later, a couple of my colleagues would claim that they heard the explosion. The rest would insist that it was too far away to be heard and that the others were mistaken.

I did not hear it. I felt it. The shockwave, widening and waning as it raced through east London, passed through my chair, through my notebook, through my phone, and through the people seated around the aquarium conference table. As it passed through me – through the acid wash of my gut, through raw, quivering membranes, through the poisoned fireworks of my brain – the wave registered as a shudder. It tripped a full-body quake, a cascade of involuntary movements beginning at the base of my spine and progressing out to my fingertips. These episodes had been getting worse lately, but I knew this was more than the usual shakes: as I felt the wave, I saw it. My eyes were focused on the glass of sparkling water in front of me. I had been trying to lose myself in its steady, pure, radio-telescope crackling. When the shock of the blast reached us, it had just enough strength to knock every bubble from the sides of the glass, and they all rose together in a rush. No one else reacted. No one else saw.

No ripple could be seen in the rectangular black pond of my phone, which was lying on the conference table in front of me. Within it, though, beneath its surface, ripples … But the Monday meeting had rules, strict rules, and my phone was silenced. Really, it should have been turned off, but I knew that it was on behind that finger-smeared glass, awaiting my activating caress.

‘Explosion’ was not my first thought. I guessed that a car had hit the building, or one nearby. These Victorian industrial relics all leaned up against each other, and interconnected and overlapped in unexpected ways. Strike one and the whole block might quiver. But it could have been nothing. Without the evidence of the glass in front of me, I might have believed that I had imagined the shock, or that it had taken place within me, a convulsion among my jangling nerves, and I had projected it onto the world.

Even the bubbles were no more than a wisp of proof that an Event had taken place; they were gone now, and no further indications had shown themselves. None of my colleagues had stirred – they were either discussing what to put in the magazine, or looking attentive. As was I. There were no shouts or sirens from the street, not that we’d hear them behind double glazing six storeys up.

But on the phone, though, through that window … Whatever had happened might now be filling that silent shingle with bright reaction. With a touch, I would be able to see if anyone else had heard, or felt, an impact or quake in east London; I would be able to ask that question of the crowd, and see who else was asking it. And I might be able to watch as an event in the world became an Event in the floodlit window-world – the window we use to look in, not out. It was magical seeing real news break online, from the first hesitant, confused notices to the deluge of report and response. An earthquake, a bomb, a celebrity death. And if you scrolled down, reached back, you could find the very first appearance of that Event in your feed or timeline, the threshold – the point where, for you, the Event began, the point at which the world changed a little. Or a lot. In front of me, in real time, the Event would be identified, located, named and photographed. And the real Event would generate shadow events, doppelhappens, mistaken impressions, malicious rumours, overreactions, conspiracy theories. More than merely watching, I would be participating, relaying what I had seen or heard or felt, recirculating the views of others if I thought they deserved it, trimming away error and boosting truth. Journalism, really, in its distributed twenty-first-century form.

(I sickened as I thought of the Upgrade, the digitisation effort taking place on the floor below, all those features I had written being plucked from their dusty, safe, obscure sarcophagus in the magazine’s archives, scanned, and run through text-recognition software. Soon they would be online. It couldn’t be stopped.)

Being denied the chance to check if an Event was indeed happening felt physical to me, withdrawal layered over withdrawal. The action would be so quick: a squeeze on the power button, dismiss the welcome screen, select the appropriate network from the platter of inviting icons on my home page. I no longer even saw those icons: the white bird of Twitter against its baby-blue background, the navy lower-case t of Tumblr, the mid-blue upper-case T of Tamesis, enclosed in a riverine bend. For something happening in London, Tamesis might be best, the smallest and the newest of those three. It had started as a way of finding bars and restaurants, and prospered on the eerie strength of its recommendations. But it was evolving into much more than that, rolling out new functions and abilities, constantly sucking in data from other networks, informing itself about the city and its users. If there had been a bomb, or a gas explosion, or even a significant car accident, Tamesis would know about it before most people, pulling in keywords and speculation from Twitter and Facebook and elsewhere, cross-checking and corroborating, and making informed guesses – preternaturally informed. Maybe that, really, was twenty-first-century journalism: done by an algorithm in a black box.

With the passing minutes the importance of the vibration diminished, but my desire to escape this room and dive into the messages, amusements and distractions of the phone only strengthened. It was right there in front of me, but inaccessible – Eddie would be greatly displeased. He was relaxed about a lot of things that might bother other bosses, but the no phones rule in the Monday meeting was sacrosanct, and I saw his point. Allow one, just for a second, and everyone would be on them the whole time. But the thought had taken root. Not only was I cut off from the sparkling constellation of others, I was cut off from myself, the online me, the one who didn’t tremor and sicken at 11 a.m. on a Monday morning, the one who charmed and kept regular hours and lived a fascinating life, not this shambles who sweltered in the aquarium. The old image of life after death was the ghost, which inhabited without occupying, and observed without possessing or influencing. But here I was, in this meeting, alive and a ghost. Death, I imagined, would be more akin to being stuck on the outside of an unpowered screen – the world still blazing away there, wherever there was, but imprisoned behind vitrified smoke.

If I could be reunited with that shining soul behind the glass, though, the happy success, not the ailing failure, I could check in with the others – Kay, for instance, sitting across from me but looking at Eddie, as mute and inaccessible as my phone. I could send her a message, see what she had been saying on Twitter, Tamesis, Facebook, Instagram … I doubted there would be anything to see. I greatly preferred the other version of me who would be doing the looking, though, the assurance and charisma of his interactions with others. He had no hands that might shake or knees that might buckle. His visage appeared only behind moody filters, hiding the sweat and pallor. He was always on his way somewhere interesting, not fleeing rooms full of people. What would become of that Jack Bick when this one was finished? I wondered. His was the greater tragedy. He had not brought failure upon himself. How I wanted to be in his company, but how bittersweet I now found those times together. It was like seeing an attractive house from a train window and thinking, Yes, what a fine place to live – and realising that the railway line ran right past its windows, the passing trains full of strangers gawping in. This was the relationship between my online and my offline. The phone is the dark reflecting pool for the monument of the self.

‘Jack?’

Kay was looking at me now, and so was Freya, and so were the Rays, and Ilse, and Mohit and the others. They were all looking at me. Eddie was looking at me – he had spoken.

‘You with us, buddy?’ Eddie said, and some of the others laughed. I forced a smile.

‘Feature profile,’ Eddie continued. Everyone looking.

How must I look to them? I wonder: the thin layer of greasy sweat pushed up by the warmth of the aquarium, the unlaundered shirt over an unlaundered T-shirt, unshowered and unshaved on a Monday morning. Was there odour? The air around me could not be trusted; I feared the tell-tale vapours that might be creeping into it. My index finger was resting on the rim of my glass, where I had been watching for tremors and thinking about the bubbles.

‘Something just happened …’

Thirty or so eyes on me. No one spoke.

‘Did anyone feel that?’

No one spoke.

‘Feature, profile,’ Eddie said. ‘What do you got for us, Jack?’ He enunciated this carefully, savouring the carefully remixed syntax.

The really bad part was that I actually had an answer to this, I was in fact prepared, but I had completely tuned out while Freya was talking, lost in ascending bubbles and the vibrating gulf between the icy crystalline world of the water and me, its observer, a low-voltage battery made by coiling an acid-coated length of bowel around a spine filled with tinfoil and bad cartilage. I searched for the correct page in my notebook, sweat prickling.

‘Oliver Pierce,’ I said.

One of the Rays pulled their head back, an almost-nod of recognition. Ilse appeared to tighten. Kay smiled, though only specialist devices aboard the Hubble Space Telescope could have detected it. The others did not react.

‘The mugging guy,’ Eddie said.

‘Yes, the mugging guy.’

‘He’s been interviewed a lot.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘He was interviewed a lot, when the mugging book came out. But he hasn’t said anything to anyone in years. Not a word. Deleted his Twitter, doesn’t answer emails …’

‘Does he have a book coming out?’

‘No,’ I said, too quickly, a mistake. Then, scrambling to recover: ‘Well, he must have been working on something – when I—’

‘Maybe he’s got nothing to say,’ Eddie said. ‘No book, no hook. How do we make it urgent?’

‘He must have been working on something …’

‘I haven’t even seen any pieces by him lately,’ Freya said. She was as bright-lit as the rest of us, but it was as if she had stepped from the shadows. I had tuned out of the meeting during a lengthy argument about feature lifestyle, her domain. We used to have a food correspondent, but after she left, food was added to Freya’s brief. Freya hated food. Her one idea had been a feature about the next big thing in grains – trying to sniff out the next quinoa, the spelt-in-waiting – which Eddie, Polly and Ilse had united in hating. Boring, impossible to illustrate. It had been a bruising business for Freya, and part of her recovery was to try to make someone else’s ideas and preparation look worse than hers had been. That someone would be me. Every month the flatplan served me up after Freya, a convenient victim if the meeting had gone badly for her. Unless I booked an interview high-profile enough to lead the feature section (not for a while now), feature profile followed feature lifestyle like chicken bones in the gutter followed Friday night.

‘Nothing on Vice,’ Freya continued, ‘nothing in Tank. What if he’s blocked or something?’

Pain, a steady drizzle behind my eyes. The quake visited my right hand, which was resting on the table in front of me, on top of my pen. I stopped it by picking up the pen and making a fist around it. The aquarium air was acrid in my sinuses, impure. What time was it? The Need wanted to know. I had to push on.

‘Isn’t that interesting in itself?’ I asked, emphasising with the pen-holding hand, keeping it moving until the quake subsided. ‘A writer has a smash hit like that mugging book. Big surprise. Awards. Colour supplements. Then, he goes Pynchon. Recluse. Emails bounce. Changes mobile number. Why? Isn’t that worth a follow-up?’

‘But he’s not a recluse,’ Eddie said. ‘He’s talking to you. Why’s that?’

I wished I knew. ‘He must have something to say.’

‘There were loads of interviews when that book came out,’ Freya said. There was brightness in her tone, no obvious malice, but I knew her game. She was trying to smear my pitch. And as she spoke, it was as if I could detect the gaseous content of each word, the carbon dioxide in each treacherous exhalation, subtracting from the breathable air in the room, adding to the fog around me. ‘And besides … A novelist … Not much visual appeal.’ She pursed her lips into a red spot of disapproval.

No one else spoke. Eddie pushed back in his chair. ‘When are you meeting him?’

‘Tomorrow,’ I said. ‘Morning. Tomorrow morning.’

‘Let’s have a back-up,’ Eddie said. ‘I want you to meet Alexander De Chauncey.’

An action took me without my willing it, an autonomous protest from my body. My head fell back and my eyes rolled; my lower jaw sagged; and I made a noise: ‘Euuhhhh …’

Another boss might have regarded this as insolence – it was insolence, after all, a momentary lapse into teenage rebellion, not calculated but real – and hit back hard, but this was Eddie, our friend. He smiled at it. ‘Look, I know you don’t rate the guy …’

‘He’s a prick.’

‘Have you met him? You wouldn’t say that if you met him. Ivan introduced us. He’s actually a great guy. Fun, creative, down-to-earth. An ideas guy.’

‘He’s a fucking estate agent.’

Eddie was away, fizzing with enthusiasm for his own proposal. ‘That’s the angle. An estate agent, but a new breed. Young, hip, creative. Progressive. One of us, you know? Not one of them. He’s got some really amazing ideas. You’ll love him.’

Every particle of my body screamed with cosmic certainty that I would hate him. ‘Maybe next month?’

The change in Eddie’s manner was so slight that perhaps only half the people in the room picked up on it, if they were paying attention: a hardening, a cooling. ‘What, you’re too busy this month?’ A chuckle from the ones who had detected the change in Eddie-weather. ‘Look, it’s win-win, Jack. If your mugging guy pays off we can go large on him and maybe hold De Chauncey for next month. It won’t hurt you to have one in the bag, to get ahead of yourself. If mugging guy is so-so, we do both. If Mr Mugging is a dud, we do De Chauncey. Yeah?’

There was no real question at the end of Eddie’s statement – more a choice between consenting by saying something or consenting by staying quiet. I chose to stay quiet. Eddie turned to his flatplan and struck out six spreads, over which he scrawled PROFILE PIERCE? / ALEX. The spread after this block he put an X through.

The flatplan was the map of the magazine – a blank A3 grid of paired boxes indicating double-page spreads, used to plot out the sequence of stories, features and adverts, letting editors decide the distribution and balance of contents: too word-heavy or too picture-heavy? Are there deserts to be populated or slums to be aerated? Editors, not generally a whimsical breed, often attribute mystical properties to the ‘art’ of flatplanning. They talk – their eyes drifting to the middle distance – of matching ‘light’ and ‘dark’, of rhythm and counterpoint, and the magazine’s ‘centre of gravity’, its terrain, its movement. But basically, the flatplan is a simple graphical tool and can be mercilessly blunt in what it shows.

Those Xed-out spreads that came between features were advertising. And each of those ads would be for a high-status brand – BMW, Breitling, Paul Smith – appropriate to the magazine’s luxury-lifestyle brief. One spread, very occasionally two, between each feature. No one commented on that, as if it had always been that way. But when I had started at the magazine there had been three or four ad spreads between features. Sometimes ad spreads would interrupt features. Advertisers would insert their own magazines and sponsored supplements into ours. The ads would experiment and try freakish new forms. They would have sachets of moisturiser glued to them, or fold-out strips reeking of perfume, or the page would be an authentic sample of textured designer wallpaper or a hologram or it would come with 3D specs. It had been quite normal for the magazine’s writers and editors to complain about the ads, about features getting swamped by them, about the magazine becoming cumbersome. We were afloat on a sea of gold, and whining it was too thick to paddle, that the shine of it hurt our eyes.

There were still grumbles about the adverts, but now they dwelled on quality, not quantity. Was this Australian lager, or that Korean automobile, really the kind of advertiser we wanted? Couldn’t the ad team do better? But Eddie was able to turn away these gripes with a sympathetic yet helpless shrug – a shrug that said, ‘I know, but what can you do?’ – and no one pushed past that.

Every year there were fewer of us to complain.

Ilse was unhappy with the inclusions, the loose advertising leaflets tucked into the magazine. One was a sealed envelope printed with a black and white photograph of a child’s face, dirty and miserable. Underneath the face was the message IF YOU THROW THIS AWAY, MIRA MAY DIE.

‘This kid, I don’t know – this kid is threatening me? They are holding a gun to this kid and threatening it? It’s a threat?’

‘It’s a charity appeal,’ Kay said. ‘They are just trying to create some urgency.’

‘It is ugly,’ Ilse said. ‘Not the photograph, a good photograph I suppose, lettering fine, but what they are saying with this is ugly, it is a threat. When I open my magazine, my beautiful magazine’ – she acted this out, closing last month’s edition on the envelope, then opening it again – ‘and, oh my goodness, this kid, I don’t even know. It is not the correct mood.’

Eddie pushed a hand into his thick black curls. Ilse had been with the magazine longer than anyone except him, and along with him was the only surviving remnant of the Errol era. Dutch, brittle, she had a temper that was the basis of several office legends: that she was unsackable, that she had once hit a sub-editor with a computer mouse, that her giant desk was not a reflection of her status as art director but rather an exclusion zone established to keep the peace. When I was new, before the office became the roomy, under-populated space it was now, I had to sit near Ilse for two days while the wall behind my desk was repainted. Two days of terrified silence. On the second day, I ate lunch at my desk and for some reason – a self-destructive, reckless impulse, a death wish – that lunch included a packet of Hula Hoops. As I crunched my way through the fourth or fifth Hula Hoop, I became aware of eyes focused through steel-framed glass, of pale skin taut over sharp cheekbones. She said nothing, just looked. The remainder of the pack I softened in my mouth before chewing. It took about an hour and twenty minutes to finish them all.

This was back at the beginning of my time, and it was commonly held that she had mellowed. Recent budget cuts she had borne with (public) silence, if not good grace. Nevertheless, art directors are dangerous as a breed. They spend too much time playing with scalpels. Here we are in the age of Adobe Indesign and Photoshop, and still they won’t be separated from those vicious little blades that come wrapped in wax paper like sticks of gum, and those surgical green rubber cutting boards. Why, if not for murder? Or at least recreational torture.

Before Eddie could answer, Freya spoke. ‘Last month it was the National Trust. That seems off, to me. I mean, stately homes?’ She threw up her hands and grimaced.

Eddie smiled. ‘Good high-quality product. Not starving kiddies.’

‘But it’s just so Boden. Where do we draw the line? Those fucking catalogues of William Morris shawls and ceramic owls and reproduction Victorian thimbles?’

‘If their money’s green,’ Eddie said with a teasing little shrug, clearly relieved to be arguing with Freya and not Ilse, who could thus be answered by proxy. ‘Look, these pay, and quite frankly beggars can’t be choosers. You want to sit in on one of my meetings with the ad team. You don’t want.’

One of Eddie’s tics – along with the suffering-in-silence hands-in-the-hair – was starting sentences with the word ‘look’. You could see why he liked it: there was that note of Blairish candour, of plain dealing. It insisted on your attention and assent. But it was also a tell. It cropped up when he felt a discussion was not going his way. When he felt, for whatever reason, that he was not being sufficiently convincing. This was a double-look.