Полная версия:

Standard of Honour

STANDARD OF HONOUR

Book Two of the Templar Trilogy

Jack Whyte

Copyright

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Copyright © Jack Whyte 2007

Jack Whyte asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins eBooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007207473

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007283354

2014-12-31

For my wife, Beverley, Endlessly patient, long-suffering, encouraging, supportive, and inspiring

Every Frank feels that once we have reconquered the [Syrian] coast, and the veil of their honor is torn off and destroyed, this country will slip from their grasp, and our hand will reach out towards their own countries.

—Abu Shama, Arab historian, 1203–1267 a.d.

The soldier of Christ kills safely: he dies the more safely. He serves his own interest in dying, and Christ’s interests in killing!

—St. Bernard of Clairvaux, 1090–1153 a.d.

THE PlANTAGENET EMPIRE

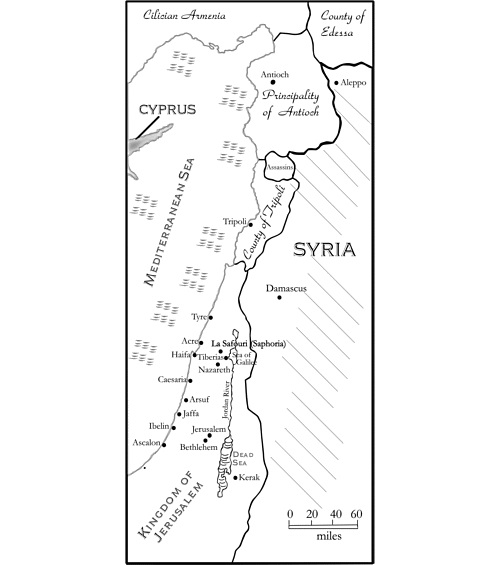

"OUTREMER," THE HOLY LAND IN 1191

Contents

Cover Title Page Copyright Epigraph Authors Note The Horns Of Hattin 1187 Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five The County Of Poitou 1189–90 Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven The Islands Of Sicily And Cyprus 1190–91 Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Keep Reading Acknowledgments About the Author Also By Jack Whyte About the Publisher

AUTHORS NOTE

Where is France? If anyone were to ask you that question casually, you would probably wonder at the ignorance that must obviously underlie it, because you, of course, know exactly where France is, having seen it a thousand times on maps of one kind or another, and it has been there forever, or at least since the last Ice Age came to an end, about ten thousand years ago. So clearly, anyone with a lick of education ought to know where it is without having to ask. And yet, as a writer of historical fiction, I have been having trouble with that question ever since I began to deal with it, because I feel an obligation to maintain a standard of accuracy in the background to my stories, and yet, were I to stick faithfully to the historical sources and absolutes in writing about medieval France, Britain, and Europe, I would be bound to perplex most of my readers, whose simple wish, I believe, is to be amused, entertained, and, one hopes, even fascinated for a few hours while absorbing a reasonably accurate tale about what life was like in other, ancient times.

In writing my Arthurian novels, for example, I was forced to accept and then to demonstrate that the French knight Lancelot du Lac could not have been French in fifth-century, post-Roman Europe, and could not possibly have been called Lancelot du Lac (Lancelot of the Lake) because the country was still called Gaul in those days and the French language, the language of the Franks, was the primitive tongue of the migrating tribes who would one day, hundreds of years in the future, give their name to the territories they conquered.

I have had the same difficulty, although admittedly to a lesser degree, in writing this book, because although the country, or more accurately the geographical territory known as France, existed by the twelfth century, it was a far cry from being the France we know today. The Capet family was the royal house of France, but its holdings were still relatively small, and the French king at the time of this story was Philip Augustus. Philip’s kingdom was centered upon Paris and extended westward, in a very narrow belt, to the English Channel, and it had only just begun to develop into the state it would become within the following hundred and fifty years. At the beginning of the twelfth century, it was still tiny, hemmed in by powerful duchies and counties like Burgundy, Anjou, Normandy, Poitou, Aquitaine, Flanders, Brittany, Gascony, and an area called the Vexin, which bordered France’s northern border and would soon be absorbed into the French kingdom. The people of all these territories spoke a common language that would become known as French, but only the people who lived in the actual kingdom of France called themselves Frenchmen. The others took great pride in being Angevins (from Anjou), Poitevins, Normans, Gascons, Bretons, and Burgundians. (Richard Plantagenet, the Duke of Aquitaine and Anjou, in many ways was wealthier and far more potent than the French king. Upon the death of his father, King Henry II, Richard would become King of England, the first of his name, the paladin known as Richard the Lionheart, and he would rule an empire built by his father and his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, that was far greater than the territories governed by King Philip.)

To all of us today, they are all Frenchmen, but that was not so in their day, and the task of making that clear to modern readers, demonstrating that those differences existed and were crucially important at times to the people concerned, is the main reason why I often have to ask myself the question I began with here: Where is France?

At the time of this story, in the days of Richard Plantagenet and the Third Crusade, the war against the Saracens under the Sultan Saladin, the Knights Templar had not yet achieved the pinnacles of wealth, power, and putative corruption that would so infuriate their contemporaries in later years, engendering envy, malice, and cupidity. But they had nonetheless made unbelievable advances since the time, a mere eighty years earlier, when their membership had numbered nine obscure, penniless knights, living and laboring in the tunnels beneath the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Within the eight decades since their founding, they had become the standing army of Christianity in Outremer, and their reputation for honor, righteousness, and obedient, unquestioning loyalty to the Catholic Church was sterling and unblemished. From obscurity, the nascent Order had moved directly to celebrity and universal acceptance, and within the same short time, thanks mainly to the enthusiastic and unstinting support of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the greatest churchman of his day, it had also gone from penury to the possession of incalculable wealth, both in specie and in real property.

From its beginnings, however, the Order had been a secret and secretive society, its rites and ceremonies shrouded in mystery and conducted in darkness, far from the eyes and ears of the uninitiated, and that secrecy, no matter how legitimate its roots might have been, quickly and perhaps inevitably gave rise to the elitism and arrogance that would eventually alienate the rest of the world and contribute greatly to the Order’s downfall.

I suspect that if, after reading this book, you were to go and ask the question of your friends and acquaintances, you might experience some difficulty finding someone who could give you, off the cuff, an accurate and adequate definition of honor. Those who do respond will probably offer synonyms, digging into their memories for other words that are seldom used in today’s world, like integrity, probity, morality, and self-sufficiency based upon an ethical and moral code. Some might even refine that further to include a conscience, but no one has ever really succeeded in defining honor absolutely, because it is a very personal phenomenon, resonating differently in everyone who is aware of it. We seldom speak of it today, in our post-modern, post-everything society. It is an anachronism, a quaint, mildly amusing concept from a bygone time, and those of us who do speak of it and think of it are regarded benevolently, and condescendingly, as eccentrics. But honor, in every age except, perhaps, our own, has been highly regarded and greatly respected, and it has always been one of those intangible attributes that everyone assumes they possess naturally and in abundance. The standards established for it have always been high, and often artificially so, and throughout history battle standards have been waved as symbols of the honor and prowess of their owners. But for men and women of goodwill, the standard of honor has always been individual, jealously guarded, intensely personal, and uncaring of what others may think, say, or do.

Jack Whyte

Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

July 2007

THE HORNS OF HATTIN 1187

ONE

“We should never have left La Safouri. In Christ’s name, a blind man could see that.”

“Is that so? Then why didn’t some blind man speak up and say so before we left? I’m sure de Ridefort would have listened and paid heed, especially to a blind man.”

“You can shove your sarcasm up your arse, de Belin, I mean what I say. What are we doing here?”

“We’re waiting to be told what to do. Waiting to die. That’s what soldiers do, is it not?”

Alexander Sinclair, knight of the Temple, listened to the quiet but intense argument behind him, but he took pains to appear oblivious to it, because even though a part of him agreed with what Sir Antoine de Lavisse was complaining about so bitterly, he could not afford to be seen to agree. That might be prejudicial to discipline. He pulled the scarf tighter around his face and stood up in his stirrups to scan the darkened encampment around them, hearing the muffled sounds of unseen movement everywhere and another, distant Arabic voice, part of the litany that had been going on all night, shouting “Allahu Akbar,” God is great. At his back, Lavisse was still muttering.

“Why would any sane man leave a strong, secure position, with stone walls and all the fresh water his army might ever need, to march into the desert in the height of summer? And against an enemy who lives in that desert, swarms like locusts, and is immune to heat? Tell me, please, de Belin. I need to know the answer to that question.”

“Don’t ask me, then.” De Belin’s voice was taut with disgust and frustration. “Go and ask de Ridefort, in God’s name. He’s the one who talked the idiot King into this and I’ve no doubt he’ll be glad to tell you why. And then he’ll likely bind you to your saddle, blindfold you and send you out alone, bare-arsed, as an amusement offering to the Saracens.”

Sinclair sucked his breath sharply. It was unjust to place the blame for their current predicament solely upon the shoulders of Gerard de Ridefort. The Grand Master of the Temple was too easy and too prominent a target. Besides, Guy de Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, needed to be goaded if he were ever to achieve anything. The man was a king in name only, crowned at the insistence of his doting wife, Sibylla, sister of the former king and now the legitimate Queen of Jerusalem. He was utterly feckless when it came to wielding power, congenitally weak and indecisive. The arguing men at Sinclair’s back, however, had no interest in being judicious. They were merely complaining for the sake of complaining.

“Sh! Watch out, here comes Moray.”

Sinclair frowned into the darkness and turned his head slightly to where he could see his friend, Sir Lachlan Moray, approaching, mounted and ready for whatever the dawn might bring, even though there must be a full hour of night remaining. Sinclair was unsurprised, for from what he had already seen, no one had been able to sleep in the course of that awful, nerve-racking night. The sound of coughing was everywhere, the harsh, raw-throated barking of men starved for fresh air and choking in smoke. The Saracens swarming around and above them on the hillsides under the cover of darkness had set the brush up there ablaze in the middle of the night, and the stink of smoldering resinous thorn bushes had been growing ever stronger by the minute. Sinclair felt a threatening tickle in his own throat and forced himself to breathe shallowly, reflecting that ten years earlier, when he had first set foot in the Holy Land, he had never heard of such a creature as a Saracen. Now it was the most common word in use out here, describing all the faithful, zealous warriors of the Prophet Muhammad—and more accurately of the Kurdish Sultan Saladin—irrespective of their race. Saladin’s empire was enormous, for he had combined the two great Muslim territories of Syria and Egypt, and his army was composed of all breeds of infidel, from the dark-faced Bedouins of Asia Minor to the mulattos and ebony Nubians of Egypt. But they all spoke Arabic and they were now all Saracens.

“Well, I see I’m not alone in having slept well and dreamlessly.” Moray had drawn alongside him and nudged his horse forward until he and Sinclair were sitting knee to knee, and now he stared upward into the darkness, following Sinclair’s gaze to where the closer of the twin peaks known as the Horns of Hattin loomed above them. “How long, think you, have we left to live?”

“Not long, I fear, Lachlan. We may all be dead by noon.”

“You, too? I needed you to tell me something different there, my friend.” Moray sighed. “I would never have believed that so many men could die as the result of one arrogant braggart’s folly…one petty tyrant’s folly and a king’s gutlessness.”

The city of Tiberias, the destination that they could have reached the night before, and the freshwater lake on which it stood, lay less than six miles ahead of them, but the governor of that city was Count Raymond of Tripoli, and Gerard de Ridefort, Master of the Temple, had decided months earlier that he detested Raymond, calling the man a Muslim turncoat, treacherous and untrustworthy.

In defiance of all logic in the matter of reaching safety and protecting his army, de Ridefort had decided the previous afternoon that he had no wish to arrive at Tiberias too soon. It was not born of a reluctance to meet Raymond of Tripoli again, for Raymond was here in camp, with the army, and his citadel in Tiberias was being defended by his wife, the lady Eschiva, in his absence. But whatever his reasons, de Ridefort had made his decision, and no one had dared gainsay him, since the majority of the army’s knights were Templars. There was a well in the tiny village of Maskana, close to where they were at that moment, de Ridefort had pointed out to his fellow commanders, and so they would rest there overnight and push down towards Lake Tiberias in the morning.

Of course, Guy de Lusignan, as King of Jerusalem, could have vetoed de Ridefort’s suggestion as soon as it was made, but, true to his vacillating nature, he had acceded to de Ridefort’s demands, encouraged by Reynald de Chatillon, another formidable Templar and a sometime ally of the Master of the Temple. De Chatillon, a vicious and foresworn law unto himself and even more arrogant and autocratic than de Ridefort, was the castellan of the fortress of Kerak, known as the Crow’s Castle, the most formidable fortress in the world, and he held the distinction of being the man whom Saladin, Sultan of Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia, hated most in all the Frankish armies.

And so the signal had been passed and the army of Jerusalem, the greatest single army ever assembled by the eighty-year-old kingdom, had stopped and made camp, while the legions of Saladin’s vast army—its cavalry alone outnumbered the Franks by ten to one—almost completely encircled them. Hemmed in on all sides even before night fell, the Frankish army of twelve hundred knights, supported by ten thousand foot soldiers and some two thousand light cavalry, made an uncomfortable camp, dismayed and unnerved, alas too late, by the swift-breaking news that the well by which their leaders had chosen to stop was dry. No one had thought to check it in advance.

When a light breeze sprang up at nightfall they were grateful for the coolness it brought, but within the hour they were cursing it for blowing the smoke among them throughout the night.

Now the sky was growing pale with the first light of the approaching day, and Sinclair knew, deep in his gut, that the likelihood of him or any of his companions surviving the coming hours was slim at best. The odds against them were laughable.

The Temple Knights, whose motto was “First to attack; last to retreat,” loved to boast that a single Christian sword could rout a hundred enemies. That arrogant belief had led to an incredible slaughter of a large force of Templars and Hospitallers at Cresson, a month and some days earlier. Every man in the Christian force, except for the Master de Ridefort himself and four wounded, nameless knights, had gone down to death that day. But the army surrounding them this day would quickly put the lie to such vaunting nonsense, probably once and for all. Saladin’s army was composed almost entirely of versatile, resilient light cavalry. Mounted on superbly agile Yemeni horses and lightly armored for speed, these warriors were armed with weapons of damascened steel and light, lethal lances with shafts made from reeds. Thoroughly trained in the tactics of swift attack and withdrawal, they operated in small, fast, highly mobile squadrons and were well organized, well led and disciplined. There were countless thousands of them, and they all spoke the same language, Arabic, which gave them an enormous advantage over the Franks, many of whom could not speak the language of the Christians fighting next to them.

Sinclair had known for months that the army Saladin had gathered for this Holy War—the host that now surrounded the Frankish army—contained contingents from Asia Minor, Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia, and he knew, too, that leadership of the various divisions of the army had been entrusted to Saladin’s ferocious Kurdish allies, his elite troops. The mounted cavalry alone, according to rumor, numbered somewhere in the realm of fifteen thousand, and he had seen with his own eyes that the supporting host accompanying them was so vast it filled the horizon as it approached the Frankish camp, stretching as far as the eye could see. Sinclair had clearly heard the number of eighty thousand swords being passed from mouth to mouth among his own ranks. He believed the number to be closer to fifty thousand, but he gained no comfort from that.

“De Ridefort’s to blame for this disaster, Sinclair. We both know that, so why won’t you admit it?”

Sinclair sighed and rubbed the end of his sleeve across his eyes. “Because I can’t, Lachie. I can’t. I am a knight of the Temple and he is my Master. I am bound to him by vows of obedience. I can say nothing more than that without being disloyal.”

Lachlan Moray hawked and spat without looking to see where. “Aye, well, he is not my master, so I can say what I want, and I think he’s insane…him and all his ilk. The King and the Master of the Temple are two of a kind, and that animal de Chatillon is worse than both of them combined. This is insane and humiliating, to be stuck here in such conditions. I want to go home.”

A grin quirked at the corner of Sinclair’s mouth. “It’s a long way to Inverness, Lachlan, and you might not reach there today. Best you stay here and stick close by me.”

“If these heathens kill me today, I’ll be there before the sun sets over Ben Wyvis.” Moray hesitated, then looked sideways at his friend. “Stick close by you, you say? I’m not of your company, and you are the rearguard.”

“No, you are not.” Sinclair was gazing eastward, to where the sky was lightening rapidly. “But I have the feeling that before the sun climbs halfway up the sky this day it will be of no concern to any of us who rides with whom, Templars or otherwise. Stick you by me, my friend, and if we are to die and go home to Scotland, then let us go back together, as we left it to come here.” His gaze shifted slightly towards the light that had begun to glow within the massive black shadow that was the royal tent. “The King is astir.”

“That is a shame,” Moray muttered. “On this, of all days, he should remain abed. That way, we might have hope of doing something right and coming out of this alive.”

Sinclair shot him a quick grin. “Build not your hopes on that, Lachlan. If we come through this day alive, we will be ta’en and sold as slaves. Better to die a clean, quick death—” He was interrupted by the braying of a trumpet, and his hands dropped automatically to the weapons at his belt. “There, time to assemble. Now remember, stay close by me. The first chance you have—and I swear it will no’ be long—head back for our ranks. We won’t be hard to find.”

Moray punched his friend on the shoulder. “I’ll try, so be it I don’t have to leave my friends in danger. Be well.”

“I will, but we are all in danger this day, more than ever before. All we may do now is sell our lives dearly, and in the doing of that, simply because my brethren are all Templars, you will have more chance to fight on with me than I would have with your companions, brave though they be. Fare ye well.”

Both men swung about and headed towards their allocated positions, Sinclair among the Temple Knights at the rear of the knoll behind the King’s tents and Moray among the hastily assembled crew of Christian knights and adventurers who had answered the call to arms sent out by Guy de Lusignan after his coronation. It was these men who now surrounded the King’s person, and the precious reliquary of the True Cross that loomed above them all.

Glancing up, Sinclair saw that it was already close to daybreak, the sky to the east flushed with pink. And then he shivered, in spite of himself, as he saw the bright, blazing new star in the lightening sky. He was not superstitious, unlike most of his fellows, but he could barely suppress the feelings of unease that sometimes welled up in him nowadays. This star had appeared a mere ten days before, exactly three weeks after the slaughter of the Templar knights at Cresson, and the sight of it stirred dread among the Franks, for it was another in a long string of strange occurrences that they had seen in the skies in recent times. Since the year before this one, there had been six eclipses of the sun and two eclipses of the moon. Eight clear signs, to most people, that God was unhappy with what was happening in His Holy Land. And then had come this blaze in the sky, a star so bright that it could be seen by day. Some said, and the priests said little to discourage them, that this was a reappearance of the Star of Bethlehem, burning again in the sky to remind the Frankish warriors of their duty to their God and His beloved Son.