Полная версия:

Whicker’s War and Journey of a Lifetime

ALAN WHICKER

WHICKER’S WAR and JOURNEY OF A LIFETIME

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Whicker’s War

Journey of a Lifetime

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

ALAN WHICKER

WHICKER’S WAR

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the men of

the Army Film and Photo Unit

who marched with me through Italy …

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

That early summer dawn in Sicily …

Being shot was for another day …

A long life was not in the script …

His Majesty got a wrong number …

They asked for it – and they will now get it …

They enlisted the Godfather …

I still feel rather guilty about that …

Very bad jokes indeed …

A passing glance at Paradise …

Struggling to get tickets for the first Casualty List …

They died without anyone even knowing their names …

I’m afraid we’re not quite ready for you yet …

You should have heard him screaming …

Hitler would have had him shot …

A beautiful woman with her teeth knocked out …

Out-gunned on one side, out-screamed on the other …

I have come to rescue you …

The call-back seemed worse than the call-up …

Whatever happened to Time Marching On …?

The Saga of The D-Day Dodgers …

Index

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

THAT EARLY SUMMER DAWN IN SICILY…

One man’s war … a return to the invasion beaches and battlefields of Italy. A sentimental pilgrimage, I suppose, to places where I expected to die. Also a salute to those I marched alongside 60 years ago while growing up watching the world explode before the viewfinders of Army Film Unit battle-cameramen. In two years of savage warfare they gave a lot; some of them, everything.

As a teenage subaltern I’d volunteered for a new role in a new Army, and found myself out of the infantry but in to far more assault landings and battles than I’d expected. My belief that war could be anything except boring went unchallenged because our cameramen closely followed the action, indeed sometimes led Italian – though that was usually just poor map-reading …

I was part of the first great seaborne invasion. The Eighth Army was learning how to do it – and so, unfortunately, were the Germans.

The Italian campaign – one of the most desperate and bloody of World War II – was 660 days of fear and exhilaration. Churchill called it the Third Front. Life was strangely intense and sharp-focussed, yet every dramatic experience vanished like an exploding shell as we moved cheerfully along the cutting edge of war towards the next violent day.

The defence of Italy cost the Axis 556,000 casualties. The Allies lost 312,000 killed and wounded – and remember, this was The Overshadowed War. After Rome the Second Front captured our headlines and at Westminster, Lady Astor won the Hollow Laugh Award by calling us ‘the D-Day Dodgers’.

As in the Great War, we subalterns had short sharp life expectations. Like those 19-year-old Battle of Britain pilots we learned to cope with this dismal forecast by being flip and jokey, but alert. It seemed to work for me – though more than half our camera crews were killed or damaged in some way while earning their Medals and Mentions.

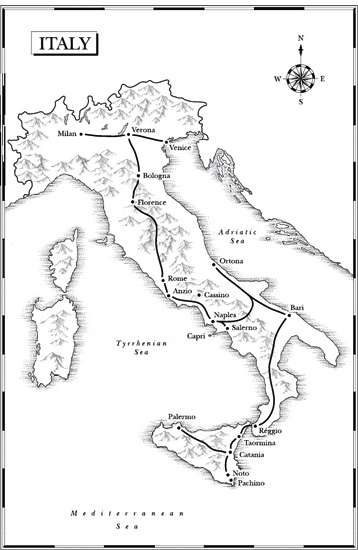

As part of a massive Allied war fleet we joined this first great invasion of 2,700 ships and landing craft and on July 10 ’43 struggled ashore on to Pachino beach at the bottom right-hand corner of Mussolini’s island, expecting the worst. Around me on that early summer dawn in Sicily, 80,000 Eighth Army troops were also landing, and looking for a fight.

Our cameramen embedded in frontline units faced bitter warfare that I suspect few of today’s young soldiers – let alone young civilians – could envisage in their worst nightmares. Among the perils in our path lay Churchill’s gamble that failed, doomed by uncertain planning and leadership: the Anzio Bridgehead, where we all ceased to be young, where 250,000 soldiers were locked into a series of battles unique in the history of World War II. There in a few weeks of savage siege warfare 43,000 of us would be blown into history: 7,000 dead, 36,000 wounded or missing-in-action – but as we fought through Sicily such horrors lay ahead, unsuspected.

I stayed with Montgomery’s desert army as it crossed the Straits of Messina to attack the Italian mainland. Then after Salerno went with the British/US Fifth Army to land 80 miles behind German lines, at Anzio. Our orders were to outflank Monte Cassino, cut Kesselring’s supply lines, destroy his Tenth and Fourteenth armies and liberate Rome. That’s all – in the afternoon we’d go to the cinema …

Breaking out of the bridgehead after 18 desperate weeks, the Fifth Army finally liberated Rome, though our war was lengthened by almost a year and many lives lost by the vanity of one insubordinate Allied General.

The Eighth fought on through the Apennines and the Gothic Line before sweeping down into the Po Valley to reach the Alps – and victory. Italy’s Dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were then hunted down and killed by their communist countrymen.

Those who doubted the strategic significance of our role in tying down 25 German divisions in Italy for two years – and the 55 divisions deployed around the Mediterranean – would have been heartened by Adolf Hitler’s reaction. As we invaded Sicily and so pinned down one-fifth of Germany’s military strength, he was controlling his wars from the Wolfschanze, his headquarters in East Prussia. He told his Generals that Citadel, the planned offensive against the Russians at Kursk, would be called off immediately. Their troops would go instead to the Italian front. That decision certainly did not make our task any lighter, but helping the Red Army was in fact our first victory – before firing a shot.

When we waded ashore on Sicily there were 2½ German divisions in Italy. Next year, as the Second Front opened, there were 24 – with three more on the way. We had made a difference. Even I made a small difference to the German SS by capturing several hundred of them, plus their General; I was also given a hidden fortune of many millions in hard currency – and then went to live in Venice. As Churchill said of our broader Mediterranean canvas: there have been few campaigns with a finer culmination!

Sixty years later I returned to Pachino to watch the sun rise over beaches where I had waded ashore up to the waist in warm Mediterranean and taken my first soggy steps on the long slog towards the Alps. I was then approaching two years of the worst – and a few of the very best – experiences of my life, when just staying alive was a celebration.

BEING SHOT WAS FOR ANOTHER DAY…

This Odyssey began before the war with a Certificate A from the Officers’ Training Corps at Haberdashers’ Aske’s School, Hampstead where, alarmed by the growing shadow of Hitler, we played at soldiering one night a week, went to summer camps and struggled with our exasperating puttees.

Came the war and I enlisted and was brushed by glory and instant power when made a Local Acting Unpaid Lance Corporal. Sewing on the lone stripe was a significant moment, rather like the ecstatic sight of that first bicycle. (I can still see mine leaning against the garden fence, all chrome and gleam. Compared with such utter bliss the sight of my first Bentley was as of dust).

I joined-up at the vast Ordnance Depot of Chilwell, outside Nottingham, and was selected as possible infantry officer material, which was worrying enough. The war had not been going well for us, and a moment’s reflection would have warned me that if I wanted a long and happy life, the infantry was not the way to go.

In pursuit of that hazardous promotion, I drove north with my friend Harry Hamilton. He had a Ford Anglia and a hoarded petrol ration. Along almost deserted wartime roads we headed for Carlisle Castle and a Border Regiment training course which would find out whether we were the right kind of cannon fodder. With a hundred potential officers we shivered through an icy January in two vast Crimean barrack rooms, sleeping on iron bedsteads and queuing to unfreeze a couple of taps. The wind whistled against cracked windows in a scene Florence Nightingale could have drifted through, the Lady with the Lamp looking concerned about her poor boys.

Ham struck a considerable blow for comfort and the conservation of life by chatting-up to some effect a girl who owned a downtown snack bar. There behind gloriously steamy windows we repaired for warmth and consolation from Army life which seemed exactly the way it was in those boys’ adventure books: cheerful, but horrible.

As we were shivering on parade one day the Sergeant’s arm came down between Ham and me – and his half of the squad turned left and marched towards the Officer Cadet Training Unit at Dunbar in Scotland. The rest of us turned right and headed for 164 OCTU at Barmouth, North Wales. We did not meet again until after the war, when he was married (‘I thought I was going to be killed and I wanted someone to be sorry’) and I was godfather to his first son. From then on our lives diverged even more as he kept marrying, and I kept not.

In the months of tough training which followed, the natural splendour of Merioneth never got through to me. A mountain merely meant something to run up with full pack, or stumble around cursing on a night exercise. A river was to wade through, a sun-dappled rocky chasm a place to cross while balancing on a rope, white with fear. It was not until I returned to Dolgellau and Cader Idris after the war that I realised I had lived, head down and fists clenched, amid scenic magnificence.

Among Army skills which remained with me for life … was how to avoid riding a motorcycle. I tried to manoeuvre my powerful beast up a one-in-two cliff path outside Harlech while the instructor insisted I stall the monster at the steepest point and then restart without losing equilibrium. That heart-bursting morning on a Welsh hillside wrestling a ton of vicious machinery to the ground put me off motorbikes for life. I have never ridden again. This must have spared me countless broken collarbones and torn ligaments. No experience is all bad.

As officer cadets, we were lorded-over on parade by the regulation Coldstream Guards regimental sergeant major straight from Central Casting: an enormous, bristling ramrod with foghorn voice. On our esplanade parade ground he spread terror and doubled platoons smartly into the sea and out again, sodden. Every day I tried to convince myself that, beneath it all, he was a dear old thing who loved his mother – but it wasn’t easy. He put me on several charges for being lazy, unsoldierly and dreaming on parade. All these heinous offences were justified, though none was pursued or I might have suffered the ultimate disgrace of being RTU’d (Returned to Unit – who said the BBC invented initials?)

I also relished one unexpected moment of glory which redirected and established my military future. I had foolishly allowed myself to be badgered into volunteering to represent my Company at boxing – a lunatic decision deeply regretted at leisure. On the night of the execution I climbed reluctantly into the floodlights of Barmouth’s packed town hall and glumly noted in the opposite corner a glowering opponent the size of a gorilla. This was a light-heavyweight? Around the ring – a place of blood and tears – sat the massed ranks, and the Unit’s excited ATS girls. They were probably knitting.

I considered how to avoid total disgrace before the brass watching from the surrounding darkness who could make or break my military career. I had to forget all that stylish and gentlemanly dancing around, the Queensberry finesse and keeping-your-guard-up I had been taught in the school gym, but to tear into him regardless and go down swinging. At least he would finish me off quickly – and I might even save disgrace by getting a crafty one in, on the way down.

So at the bell I leapt from my corner and hurled myself desperately at the gorilla in a frenzy of hopeless determination, arms going like a windmill. It was the least scientific approach in boxing history. Within ten seconds of our violent clash in the centre of that brilliant ring, my enormous opponent was lying unconscious at my feet. Never again in an uninspired sporting career was I to feel such surprise, or receive such applause.

When I recovered from my amazement I was suitably modest – as though that sort of thing happened all the time. The gorilla was brought round with difficulty and carried away through the ropes with impatient disdain, towards some tumbril. The ATS didn’t even bother to look up.

You can achieve quite a lot in ten seconds, and my reputation as a quiet killer with fists of iron spread through the unit. The Commanding Officer called me in to take a thoughtful look at this unexpected whirlwind in his midst. The girls in the Mess hall giggled at their mean street fighter and gave me larger portions, for Barmouth was a tiny coastal town miles from any excitement. Even the drill sergeants spoke to me approvingly – and that’s unnatural. The RSM shouted no deafening threats for several days, and the rest of the Company ‘D’ backed away politely when I approached the tea urn.

However, retribution was not to be avoided: the Finals were already being advertised. Next Saturday night my aggressive bluff would be called. I was about to blow my reputation on the biggest night of the sporting season before Judges measuring me as possible Officer material. I briefly considered desertion, but finally and with growing concern went reluctantly back to the town hall wondering which ferocious man-mountain would emerge to wreak terrible revenge upon an upstart pretending to be a boxer.

My seconds bravely urged their champion to Go In and Kill Him, whoever he was. They only had me to lose, and there were plenty more where I came from. Once again I climbed glumly through the ropes and towards the scaffold, into a brilliance where no secrets could be hidden. I knew that this time my tactics would be no surprise. I should have to dance-around like a pro, and box. There was a price to pay for all that limelight. I resolved to sell my life as dearly and quickly as possible, and then step back into the shadows again. Barmouth had an efficient little hospital.

I looked around anxiously for my nemesis. The stool opposite was empty – a stage-managed delay, no doubt, to increase the suspense. We waited. It stayed empty. The pitiless ATS, hungry for more blood, were getting restless.

It slowly dawned upon me that I had underestimated my own publicity. My opponent, evidently a man who believed what he heard, had Gone Sick. His strategic withdrawal on medical grounds gave me a walkover. I received another ovation even more undeserved than the first and instantly retired from boxing forever, undefeated. Quit fast, is my theory, while you’re ahead and uninjured.

I remain convinced the reason I walked through OCTU with high marks and emerged as a teenage officer was due, not to conscientious study or aptitude, not to all that square-bashing, sweat and effort – but to one lucky Saturday night punch that connected.

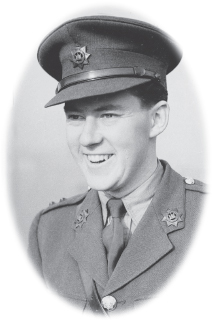

Since my Father’s family came from Devon I was commissioned into ‘The Bloody Eleventh’ of the Line, the Devonshire Regiment. Feeling chipper and dashing in my service dress and gleaming Sam Browne, with that hard-won Pip on my shoulder, I’d stride through Mayfair, acknowledge a few salutes and be perfectly happy with my lot. Being shot was for another day.

Uplifted, I left my first-class Great Western carriage and reported for duty to the regimental Adjutant at Plymouth’s Crownhill Barracks. To my disappointment he was not a fearsome Regular polo player with rows of brave ribbons, but a burbling beery ex-Territorial from Fleet Street, of all places. I felt he was the wrong sort of High Priest, playing in the wrong game. There may be nothing lower than a Second Lieutenant, but every volunteer needs a dashing role model.

However when I returned to my quarters, a batman had unpacked my kit, laid out the service dress, repolished buttons and Sam Browne, and run my bath. I had recently been living the roles of bored Lance Corporal, then weary Cadet. Now I had become overnight an Officer and a Gentleman. A little glory, with no visible risk. The war was never as good as that again, ever.

I savoured the moment. It seemed that running up all those mountains had been time well spent – despite the current prospect, as an infantry platoon commander, of the Army’s shortest lifespan. I went for a snifter with the other chaps in the Mess, as we always say.

Soon after those triumphant moments in Plymouth, I prepared to pay the piper: Movement orders came through and I was suddenly a reinforcement, reporting to an unknown regiment in training at a remote place called Alloa. This had an undulating hula-hula lilt about it, like a magical posting to some romantic Polynesian isle. Could Whicker’s Luck be holding?

No, it could not. Alloa turned out to be, not an exotic South Seas greeting but a grey and mournful Scottish industrial town in Clackmannanshire. The Battalion of East Surreys billeted in its sad empty houses was route-marched through the rain around Stirling. The Mess was a damp pub, the senior officers Regular wafflers, the NCOs morose, the men despairing. As one of the newer Crusaders, I found the atmosphere unjolly.

Depression grew. The solitary bright spot was my mandatory embarkation leave, after which our troopship would sail out across the Irish Sea to face the mines and submarines that were decimating Britain’s remaining fleets and then, if we survived, the German army. We would be last seen steaming, it was believed, to Africa.

Before leaving Home and Mother for ever I was anxious to get a little mileage on the social scene out of my brand new service dress and lone pip. The journey back to London in a dark freezing wartime train offered standard depression, but next day came a welcome invitation to a farewell lunch at 67 Lombard Street given for me by an uncle, a City banker with Glyn Mills, to celebrate my elevation to elegant cannon-fodder. It was a pleasant meal. It also probably saved my life.

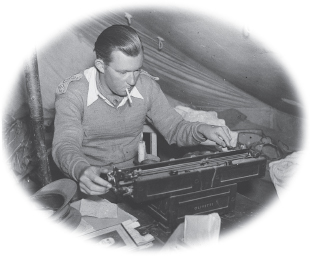

The other guest happened to be a Whitehall Warrior, a daunting blaze of red tabs and crowns and ribbons from the War Office who, over the port and Stilton, mentioned that one of his brand new units was looking for a young officer with news sense to join the Army’s first properly-organized combat Film Unit which was about to leave for some hazardous secret landing in enemy territory. Could I, he wondered, could I direct sergeant-cameramen in battle? There would be a lot of action.

It took me a nanosecond to volunteer for this unknown experience, anywhere at any time. It sounded like adventurous suicide – but it was stylish.

I returned to poor grey Alloa and its sullen soldiers, clutching a glimmer of hope amid their mass dejection. Next day the War Office offered me the posting. It was a decisive redirection, and an escape. I would be going into action before the East Surreys, but not with them. If I had to go and fight an enemy, I did at least want to get along with my own side.

A LONG LIFE WAS NOT IN THE SCRIPT…

So Whicker’s War started prosaically in a black cab driving through empty streets towards the Hotel Great Central at Marylebone Station, then the London District Transit Camp. It was the first of many millions of travel miles around Whicker’s World, though this time I was heading hopefully into the unknown and wondering what the hell was about to hit me.

At the reception desk I asked for AFPU. The corporal clerk checked his long list. ‘Army Field Punishment Unit, Sir?’

‘No,’ I said, doubtfully. Surely the General had not tricked me? ‘At least – I hope not.’

All was well. AFPU was assembling and preparing for embarkation. As far as I was concerned, there was no hurry – the West End would do fine for a few weeks, or more. Then we’d see about Africa or wherever.

One of my first Army Film and Photo Unit duties seemed close enough to Field Punishment. As the newest, youngest and greenest officer, I was instructed to give the whole unit an illustrated lecture on venereal disease and the dangers of illicit sex in foreign climes, a subject on which I was not then fully informed. The order that someone had to lay an Awful Warning on the Unit before it went to war had come amid masses of bumf from Headquarters and been passed down the line to be side-stepped with a hearty laugh by every available officer … before stopping at the least significant.

A callow youth, but aging fast, I faced that parade of world-weary 35-year-old family men who seemed like knowing and experienced uncles. There were a few grizzled Regulars who at various postings around the world had obviously looked into the whole subject quite closely. It was not an easy moment. However, I gave them the benefit of my inexperience and they were most tolerant, listening as though I was telling them something new. Well, it was new to me.

The Great Central was plush and comfortable, after field kitchens and empty billets in Cumbria. I passed some mornings drilling our assorted band of cameramen in Dorset Square, NW1. Fresh from the ministrations and ferocity of a Guards RSM at OCTU, I was quite shocked by their casual and unmilitary bearing – and they didn’t much care for mine, either. However I shouted a lot, and they fell into some sort of shape.

I was told to take them on a route march. I always found this a boring and pointless exercise so led them, not round and round Regents Park, but through such wartime bright lights as remained in the West End. Down Edgware Road to Marble Arch, where traffic waited while we crossed haughtily into Park Lane, then left for Piccadilly, up the hill, past the Ritz and left again into Bond Street. Such a route brightened the tedium of the march for us all; at least we could look into the shop windows as we strode past.

It would have been ideal for Christmas shopping, had the shops anything to sell and my Army pay been better than a few shillings a week. We were doubtless contravening a stack of regulations but even wartime Oxford Street was more visually entertaining than the country lanes around Dolgellau.