скачать книгу бесплатно

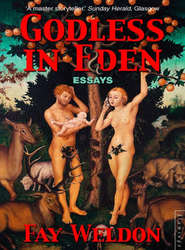

Godless in Eden

Fay Weldon

A selection of lectures and essays contributed to newspapers, magazines and books over recent years, revised for this volume and all highly relevant to today.In these essays find a portrait of the times, to help us map our way through the new Garden of Eden, in which men hold the baby and women the mobile phone. The garden is timeless, its beauties are ineradicable, the angel’s blazing sword no longer bars the way – so what’s going wrong? Tricky to see the wood for the trees in this new-old land, hard to find a Third Way through: let this collection point the way.From the changing face of government, the feminisation of politics, the stamping of the warrior foot, to whence and whither Feminism, via the dangerous new cult of Therapism, to our turbulent and benighted Royals, brushing up against the famous (Roseanne, Jamie Lee Curtis, Jean Paul Gaultier) on the way – it’s all here. Plus a rare glimpse of the author’s life and loves.

FAY WELDON

Godless in Eden

A book of essays

Contents

Cover (#ua1ccaca7-275d-51c8-bbb8-8502e38baeae)

Title Page (#uec4c8ba2-5db5-53c4-a469-8eecf853a040)

The Way We Live Now (#uc174d3d3-0008-5304-a19f-90f94caa4c16)

The Way We Live As Women (#ua10e83b8-91a4-5808-b5aa-e14d04bf4d2a)

A Royal Progress (#litres_trial_promo)

This Way Madness Lies (#litres_trial_promo)

The Changing Face of Government (#litres_trial_promo)

Brushing Up Against the Famous (#litres_trial_promo)

Growing Up and Moving On (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliographical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Way We Live Now (#ulink_c4fcc8e2-a733-5991-8d54-b5b37c3d8ab8)

A new Britain indeed: a Third Way, a great sea change in how we see ourselves. Fifty-eight million people, in fact, in profound culture shock. To determine how we live now, first determine how we lived then.

Pity a Poor Government (#ulink_7ed11f51-a7ec-5a3a-9580-cefdc3b31ef8)

Behind the Rural Myth (#ulink_8cd5ca5a-0214-5535-8e47-0e21b18c3c67)

Mothers, Who Needs ’Em? (#ulink_c6f617b3-c827-55ad-bd0a-8111e525d524)

The Feminisation of Politics (#ulink_b1fdd241-5f0e-5b16-a663-daa3efbd5158)

What This Country Needs Is: (#ulink_5f8463ca-e19d-574a-84b0-1f73d174fc81)

Take the Toys from the Boys (#ulink_bacd829a-69e3-50e4-87a7-a5cdf924ba9c)

From The Scotsman Millennium Lecture, delivered at the Edinburgh Book Festival, summer, 1998.

Pity a Poor Government (#uc174d3d3-0008-5304-a19f-90f94caa4c16)

Adam and Eve and Tony Blair. The beginning and the end: or at any rate as far as we’ve got at the close of the fourth millennium since the Garden of Eden, when we all began, and the second since Jesus, when we started counting.

But these things may be circular; the end may yet turn into a new beginning. We now have a New Adam and a New Eve (if the same old Cain and Abel kids). God is no longer seen to exist, to bar the door with flaming sword. The bearded patriarch has been replaced by Mother-Goddess Nature. The happy couple walk again in paradise. The Garden, mind you, is pretty battered these days, it lacks its ozone layer, it is buffeted by the storms of global warming and so on. But at least the serpents of hunger, poverty and ignorance have slid off into the undergrowth, driven out over the centuries by marauding parties of the Great and Good.

Pity any poor government as it tries to keep up with unprecedented social change and the collapse of the old ways of living, dealing as it has to with an electorate still immersed in the old myths of what we are and how we hope to be, obliged to piddle about with Ministries for Women when what we need is a Ministry for Human Happiness. Changes in the female condition, however welcome, have had their effect on men and children too. Takes two to make the next one – and our evolution as a species, over too many millennia to count, suggests to us most forcibly that we are all inextricably interlinked, and if we try too hard to escape our conditioning, fly too obstinately in the face of our human and gender nature, we will be very miserable indeed. But what are we, if we don’t try? Let government admit a paradox, and help us all pursue our happiness, not just some of us our rights.

The young couple, the New Adam, the New Eve – he beginning to feel the effect of the lack of a rib, she taking over the gardening: their life expectancy now in the late seventies (him) and the early eighties (her) – have in returning to the Garden been returned to innocence: they walk about its glories in a daze. Innocence may not be enough if they are to remain, this time round, in the state of grace we want for them. Let them have some information.

I can’t cover a thousand years of gender politics but I can just about manage the last hundred years. The great advantage of being no longer young is that what to many people is dead history to me is living history, if I add in my mother, that is, who is alive and well and thinking and ninety-one. Since she was there for the decades I was not, between us we can set ourselves up as experts on the century.

I spent my early years in New Zealand, where the education was based upon ‘the Scottish system’. By which is meant that the young are not trusted with independent judgement, and no-one asks ‘what are your feelings about this?’ because your feelings are irrelevant. We learned what others older and wiser than ourselves had to say. We quoted authority if we wanted to prove a point. (In those pre-television days it was possible to take authority seriously. Put Locke, Berkeley and Hume on a late night chat show and you’d soon lose respect for them.) In 1946, my family, mother, grandmother, sister and myself, took the first boat ‘home’ after the war, and I went to a girls’ grammar school in London which expected its pupils to join the great and the good and work for the betterment of mankind. Many of us did. And later I went to the University of St Andrews, where I developed the art of rhetoric. Thus: you make your case, overstating it dramatically. Your opponent does the same. In response you reduce your argument a little: so does he. Thus a consensus, or at any rate a moderation of extreme views can be reached. Except of course if you’re arguing with someone who doesn’t understand the rules of engagement, and they usually don’t down South, you’re in trouble. Others conclude you’re hopelessly argumentative, given to rash overstatement, and would be well advised to stick to writing fiction, which as everyone knows, and as my mother pointed out to me long ago, is all lies and exaggeration anyway. You make a statement: they leave the room.

It was my Professor in moral philosophy at St Andrews who, when obliged by new university directives to accept females into his class – there were three of us – declined to mark our essays or acknowledge our presence, other than from time to time to remark, with a toss of the bald head, that females were not capable of moral decision or rational judgement. The only conclusion we could come to was that we were not female. That was in the early fifties, of course, and in those days to be denied ‘moral decision’ and ‘rational judgement’ was meant as an insult. Today a young person might well interpret the remark as a compliment. Feeling takes such precedence over morality and judgement, emotional response is declared to remain so much the woman’s prerogative, that it is the young men in the class who would be the ones to feel inadequate, and long to be women, just as we then longed to be men, to be allowed out after our begrudged education into the great wide world of adventure, excitement, earning, and freedom. Not into the domesticity which seemed to be our fate, both as natural born women and because it was so difficult for a woman to earn anything other than pin money. And today’s young man might well find himself the solitary male in a Gender Studies Class expected to stay quiet when the female lecturer tells the class that all men are potential rapists.

When my mother observes, as she did the other day, that when she was a girl only working women wore blouses and skirts, and that a lady would be horrified to be seen in anything but a dress, and equally horrified if a working woman turned up wearing something in one piece, you realise how profoundly and invisibly and silently things can change, and how easy it is to forget the kind of society we once were, as we try to make sense of the one we have now. You understand why the office liked you always to wear a suit to work, and wearing a dress made them, and you, feel uneasy, and why the BBC got so upset in the sixties if you wore trousers to a meeting.

Why, I asked my mother, if there are only six million more people in this country than there were in 1950, and this is only a ten percent increase in the total population, is it so difficult to get along Oxford Street for the crowds? And why is it that the simple purchase of a pair of shoes these days takes so long and requires a lengthy session with a crashing computer? To which she replied ‘Because once upon a time everyone used to stay home, you silly girl. They were poor. Their one pair of shoes was wet and they couldn’t go out until they were dry. They didn’t even aim to have two pairs. No-one ate in restaurants, bread and cheese was the staple diet and you got them from the corner shop and paid cash, and if you didn’t have cash you went without. And that was in the fifties – things were twice as quiet when I was a child.’

My mother’s parents, at the turn of the century, ran to a cook and a maid who lived in, and had one half-day off a week. They were certainly not out littering the streets, buying shoes or overcrowding public transport.

In the East End of London, before bombs razed so much of it during two world wars, and the planners got busy with their theories, nearly everyone lived within walking distance of work. And how they worked! In 1901, we had 75,000 boys under fourteen in the factory workforce, and nearly as many girls. The school leaving age was thirteen and child labour was common in spite of it, and it was normal for women to work before they had families. But not after, if they could help it. In the civil service and in teaching, what was called the Marriage Bar meant a woman had to give up her employment – in blouse and skirt, of course – when she got married. Otherwise who would run the nation’s homes? A whole lot of women just got married secretly, of course, and failed to tell their employers.

Halfway through the century, by the time I was being taught by Professor Knox, though the Marriage Bar was gone, it was certainly assumed that an educated girl chose between a personal life and a career. Now it is assumed that somehow, what with the washing machine, the microwave, the vacuum cleaner, and this strange thing called childcare, which is another woman looking after her child for less than the mother earns, she will be able to manage both. And she can, just about, and often wants to, and often has to. And it can be hard. We have paid a heavy price for our emancipation, but more of that later.

And when I say people worked hard then, believe me they work harder now. My mother views with horror today’s average working week of forty-eight hours – and middle management works sometimes sixty or seventy, plus the journey to and from work – saying that even before World War II the attempt was to get the figure down to thirty-five. And that when in the late fifties she worked as a porter on London’s Underground – the winters were cold and staff were issued with heavy greatcoats, for which she was thankful – even then the staff worked only a forty-hour week. What happened? And as for part-time work – the kind women with children so often do – this is usually an employer’s definition and doesn’t necessarily mean shorter hours, just that the employee works without holiday or sick pay and has no statutory rights. I know ‘part-time’ college lecturers who work longer hours than the full-time staff, but for less money, and are still grateful. It’s that or nothing.

Of course things have improved. They must have. Our life expectancy is greatly increased. My mother’s life expectancy when she was born was fifty-two years. My father’s was forty-seven. A girl child born today can expect to get to eighty-one, a boy child seventy-six. The gender gap in this respect has neither closed nor narrowed. Women are born to live longer on average than men, in the human species as in most others. At the beginning of the century one hundred and sixty males per million did away with themselves: the figure for women was forty-eight. Now it’s down to one hundred and four males and thirty females. Woman is not so given to despair, it seems, as Man, and though the totals drop, thank God, they stay pretty much in the same gender proportion, three times fewer women than men. We both mostly do away with ourselves when we’re old and lonely. We were not bred for loneliness, though the contemporary world forces too many of us into it. The government plans to build 4.4 million new housing units, to house those expected to live alone in the next decade, and that figure rises steadily. As Patricia Morgan at the Institute of Economic Affairs points out, in a booklet on the fragmentation of the family, men’s disengagement from families is of immense and fundamental significance for public order and economic productivity. This is something which is only just beginning to be acknowledged – as we blithely head for a situation in which, by the year 2016, fifty-four percent of men between thirty and thirty-four will be on their own.

So pity the poor male as well as pity the poor government. One’s anxiety on their behalf has less to do with girls doing so much better at school exams than boys, which they so famously do, but with changes in society which make it difficult for us all to do what comes naturally. That is, to fall in love, marry, and live happily ever after in domestic tranquillity, even though we prefer now to do this serially. The late twentieth century is wreaking havoc with our aspirations to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. May we please have our Ministry for Human Happiness? Or if the government really wants to be useful, and preserve the marriage tie and so forth, thus saving itself large chunks of the £800 thousand million annual benefit budget spent mopping up the mayhem left by divorce, it could institute official stigma-free dating agencies, and set about arranging sensible marriages. The self-help system seems to be breaking down. And the steadiest citizen is the married citizen, and the one most pleasing to the State, tied down and sobered by kids and mortgage obligations.

My mother and I, of course, both have to thank the twentieth century for our continued existence. Let me rephrase that. Were it not for medical advances we would neither have seen so much of it. I would have been dead twice, once for lack of antibiotics, once for lack of plausible surgery. So would she. I would have three surviving children, not four. One would not have survived birth. Mind you, were it not for the advent of contraception, I might have ended up having ten. When Marie Stopes worked in London’s East End at the beginning of the century there were women around who had survived twenty children or more: but the normal fate of the married woman was to die young from repeated childbirth, contraception being both illegal and seen as immoral. For every child she carried, Stopes estimated, a woman’s chance of dying in childbirth increased by fifty percent. If the marriage rate then was a mere one in three I am not surprised. Marriage might have meant status and children, and even, in George Bernard Shaw’s phrase, been a meal ticket for life for women, but was still too often a death sentence, especially amongst the poor. Things are better now: infant and maternal mortality is way, way down to almost nothing – from over one in ten in 1900 to less that four per thousand now – but with improved health, prosperity, the advent of contraception and women’s control of her own fertility, comes a new set of problems. So it goes.

My mother at the age of five, when first required to go to the little Montessori school around the corner, set up such a wail that my grandfather, a novelist, came down the stairs in his silk dressing gown, waving his ivory cigarette holder and said what can be the matter with little Margaret? To which the reply came she doesn’t want to go to school. ‘Do you want to go to school, Margaret?’ he asked, and my mother replied no, though she knew even then, she told me, that it was a life decision and she’d made the wrong one. My grandfather said, ‘Don’t send her then,’ and went upstairs again, and they didn’t. She stayed at home and read books and by the age of twenty was writing novels with her father.

Education for my mother and myself was for its own sake. It was not training, as it is now, for the adult world of work. The motive behind the education acts of the nineteenth century, which made school compulsory, was not by any means purely philanthropic: rather it was to accustom the children of an agrarian society to industrial ways, so by the time they left school they’d have got into the habit of turning up at the factory even when it was raining and cold, they felt poorly, or their shoes were wet and it was Monday morning. Monday was always a bad day for turning up at work. And the truant officers of the new compulsory schools, the morning and afternoon register, and the sick note required to prove illness, did indeed quickly train the new generation to daily work in the factories, bother reading and writing.

Likewise today we train our children, through longer and longer years, from their first day at the creche or the playgroup, to their last day at college, to turn up, to be there, to answer the register, to compete in exams as later they will for jobs, computer fodder in the new technological society, as once they were factory fodder. It is the effective use of computers we care about, just as once we cared about getting a return on our new industrial machinery: alas, machinery works day and night and doesn’t tire, as humans will.

Our children, training for their future, in which there will always be too many workers and not too few, and so a permanent level of anxiety to keep everyone striving, end up living in an examination culture: they are tested and tried on entry to playgroup, they have SATS at 7, 11 and 14, GCSE’s, A-levels, secret personality records and all. What price the old hated eleven-plus now? That exam was as nothing. Who wanted to go to the grammar school, anyway, it separated you out from your friends. Passing it was the problem, not failing it.

Life for the child mid-century was comparative heaven. No over-trained teachers, no national curriculum, and very little truancy, why should there be? School was where you went to meet your friends: education was a by-product: they were small, quiet places. Holidays were longer, the years spent in schools were fewer, educational standards were higher. And even so, my mother didn’t want to go.

Mid-century I was lucky. I got the best of perhaps any education system the world has had to offer. Under Mr Attlee, the last of the great disruptive wars behind us, having got off the boat from New Zealand in 1946, a small family of female refugees, without possessions, into the confusion and turmoil of that grey, pock-marked, war-torn city, London, with its rationed food and its icy cold, all of us living in one room with only a glimmer of gas to light and warm it, the State plied me with orange juice and cod-liver oil. It not just sent me to a ‘maintained’ grammar school, but paid for me to go, bought me my clothes, gave me free meals, sent me to university when I was seventeen to study Economics and Psychology and become part of the future. What you have in me is what the Attlee government made of me. I got a student’s grant of £167 a year plus tuition, paid for me by the London County Council, which seemed to me to be unbelievable riches, and which indeed, if you worked in the coffee shop in the evenings, was enough to keep you and indeed even buy you a second pair of shoes. And in the summers you hitched South: the world after the war seemed a safe and gentle place: it had got its violence out of its system. Now the violence is in the tent, not out of it. Forget hitch-hiking, we feel we can’t even let our children walk to school alone in safety. Lacking an outside enemy, the attack from Mars or a meteor from outer space, I fear it may well stay like that.

Conflict at the turn of the century, and indeed up to the middle of it, was solved by war, male antlers locking, carnage on the battlefront. War, at least in the mind, if not so much of course by those compelled to participate in it, was to do with courage, chivalry, sacrifice, nobility, prowess, endurance, patriotism. Traditional male virtues, now much despised. These days in our female way we negotiate, cajole, tempt, explain, forgive, apologise, touchy-feel our way to world peace, while small savage macho wars, mini-skirmishes, little spasms of ethnic cleansing, break out here and there.

The International Monetary Fund bales out the Japanese, the Russians: we look after our economic relatives: old enmities are forgotten. And of course this is preferable to war. But without our external enemies we turn inwards: societies and individuals go on self-destruct benders. Crime, drugs, the break-up of the family, the abandonment of children, the loneliness of the individual, the alienation of the young, the pause button so often on the sadistic act of violence on the TV: are all features of today’s peaceful, caring society. And perhaps they are all inevitable. Jung would talk about a process called enantiodromia, when all the currents of belief that have been running one way suddenly turn and run the other, in the same way a river zig-zags rather than flows steadily down a hill, reversing its direction when too much pressure mounts. The more smoothly the confining, caring, peaceful society seeks to conduct itself, the more likely some of its members are furiously to run in the wrong direction, lost to all responsibility and decent feeling, vandalising and tearing everything to bits as they go. It wasn’t what they wanted: it was never what they wanted. What they wanted – because the source of the trouble is mostly male – was to be allowed to be men in a society which so disapproves of maleness.

Signs of maleness – interpreted as aggression, selfishness, sexual addiction – are treated by the therapists and counsellors, who take the place of the old patriarchal priesthood: they are the new pardoners, forgiving our sins for the payment of money, releasing us from personal guilt. Women are confirmed in their traditional self-absorption: seek the authenticity of your own feelings, they cry. Go it alone! You know you can! Assert yourself, your right to dignity, to personal fulfilment! Never settle for second best.

And of course they are right, except, in the face of such stirring advice, and because in the new Garden of Eden men and women can, when once men and women couldn’t, marriages and relationships crumble and collapse. According to a recent poll in the women’s magazine, Bella, more than fifty percent of young women think a man isn’t necessary in the rearing of a child, and seventy-five percent think that if she wants to conceive a child when she doesn’t have a partner it’s better to go to a sperm bank than have a one-night stand. Seventy-five percent. Back at the turn of the century sex was something women put up with in return for a wedding ring and all that went with it, not something they were meant to enjoy. So what changes, in spite of what a lot of other women’s magazines have had to say on the joys of sex in between?

I am not lamenting the past. We live a whole lot longer than we did; that must prove something. Though quite how we keep our Zimmer frames polished I don’t know, as both the birth rate and the marriage rate falls. Many of today’s young will grow up to live alone and not with families: friends and colleagues will have to look after us, the New Adam and the New Eve, when we grow old, or break a leg, or are made redundant, or go mad or whatever. What price independence and self-assertion then? The State is increasingly determined not to look after us, and if our families are fragmented, how can we look after ourselves?

We are all so much weaker than we believe, than the myth of the strong man, even the new one of the strong woman, allows us to be. We need all the support we can have. And as for our financial arrangements! Good Lord, you can’t trust them. Banks collapse, as do whole national economies, nothing is secure, not even your Insurance Company, not even your PEPs. It’s understandable, I take the view. I belong to the robbed generation. I started work at the Foreign Office in 1953 – earning £6 a week as a temporary assistant clerk; I worked for some fifteen years, here or there, before I became self-employed, on PAYE, paying out a vast proportion of my weekly pay packet, or so it seemed to me at the time, for my Social Security stamp. Now I get the old age pension they promised me and it’s 44p a week. Robbed! And what about all those who having no savings, no longer able to earn, endure the indignity of having to ask for income support? Their mistake, having been told they were providing well enough for their futures, was to believe what they were told. Successive governments simply did a Maxwell with the pension funds, and didn’t even have the grace to acknowledge it, let alone jump overboard.

The State is increasingly cavalier with its dependants. I know of a man with two artificial legs who because he can walk across a room – just – doesn’t get incapacity benefit any more. It was withdrawn in the last so-called fraud purge, a few months back, when everyone on incapacity benefit was called to a fifteen minute interview with a non-specialist doctor and the lists cut across the board by some ten percent. Just like that. Sure you can appeal but if you do you lose a whole set of other benefits while you wait, and then how do you eat? Is so much misery worth so small a saving to the State?

The matter of the burden to the tax-payer of the benefit bill preoccupies government to an absurd degree. States with any spare money tend to go to war, and then we pay for that. Look at the books. Total government receipts, 1998, £309 thousand million. Total government expenditure £320 thousand million. We borrowed £11 thousand million from ourselves to balance the books. (You can get all these figures from the back of your Economist Desk Diary. Take off a few noughts from the sums and it’s no different from adding up your own cheque stubs.) Out of that £320 thousand million, Social Security costs us a mere £79 thousand million. I suspect one way or another we’d go on paying the same taxes even if we stopped spending on our poor relations altogether, and allowed the unemployed, the undertrained, the sick, the weak and the inadequate, the helpless in our highly complex society, to starve to death on the streets. And what kind of family would we be if we did this? How would we live with ourselves?

One of the phenomena of the late twentieth century has been the growth of political correctness, of self-censorship, a quite false belief that we have reached the pinnacle of proper understanding, and a fear of saying what we think in case we offend our friends. It becomes important that we all think the same: and indeed, the rise of emotional correctness requires that we all feel the same. We allow ourselves as little freedom of thought as if we were Marxist-Leninists, even though there’s no-one around to put us in prison. Sexism, it is held, contrary to the evidence of the eyes and the ears, can flow only one way, from man to woman, just as racism can flow only from white to black. That both are now two-way streets we find difficult to accept.

Sometimes it seems to me that with the fall of the Berlin wall freedom fled East and control fled West. Jung’s enantiodromia at it again. Turn, and run the other way down the tramlines. In Russia now see the worst excesses of venture capitalism and personal freedom, wealth which breaks all sumptuary laws brushing up against extreme poverty, an abundance of crime, coercion and murder, and the flight of altruism. While here in the West we have the creeping Sovietisation of our culture: the advent of a dirigiste government: we are controlled, surveyed, looked after, nannied, bureaucratised. We live amongst secrets: our news is manipulated. We all know it, but don’t much care. We have direction of labour. What else is Welfare to Work? If you can’t get your own job, take the one we give you. On which I notice the government spent £200 million last year, and did get a few actually back to work, but for the most part only temporarily. And for every person who got a job there must be another one put out of work – how can it be otherwise, when we still have a seven and a half percent unemployment rate. Wouldn’t it have been cheaper to just go on paying out benefits and saved everyone a lot of aggravation, humiliation, cold calling and letter writing? Or better still created work for people to do? But that would interfere with the Bank of England’s belief that there is a ‘natural’ rate of unemployment – defined by them as the lowest rate compatible with stable inflation. They like it pretty much as is – not too high to cause rioting in the streets. High enough to keep workers in a state of anxiety and doing what they’re told. In the light of such official or semi-official policy, Welfare to Work projects look oddly like window dressing. Or, less cynically, the thinking goes like this. True, we need a calculable pool of people standing around doing nothing, to cool an overheating economy – but it’s just so irritating when they stand around. Let them at least be seen to be working at not-working, which is what the new Jobseekers’ Allowance amounts to.

Since the unemployed appear to be burnt offerings to the stability of our economy, martyrs in the cause of the low inflation and the high interest rates which keep the City happy, I think they should be treated with vast respect and allowed to live in peace, dignity and the utmost comfort.

As for the employed, the conviction seems to be that if only everyone works longer and harder, women alongside men, we’ll all be better off. But better off how? Where’s our Five-Year Plan? What exactly is all this effort for? And has no-one noticed that in spite of having the longest working hours in Europe we have the lowest productivity? Of course we do. We’re exhausted.

And we’re certainly no longer working for the children: they poor things are Kibbutzised, taken away from their parents and returned to them only at nights, so the parents are free to work to make the desert bloom. Which is all very well, but there’s no desert outside the window when the children look, and no drastic emergency, just a whole lot of new cars and new roads and new buildings and shoe shops and the Millennium dome.

We live now under Ergonarchy. By Ergonarchy I mean rule by the work ethic. Forget Patriarchy, rule by the father, it’s Ergonarchy which is woman’s current enemy, now that she’s joined the workforce. While she was doing battle with Patriarchy, Ergonarchy sneaked in under cover of darkness and ambushed her. Ergonarchy insists women work but goes on paying them less. This isn’t because Ergonarchy is male – Ergonarchy’s an automated accountant, neuter and blind and unable to tell one gender from another – but simply because women, if they have children, can’t give their bosses the time and attention they require, and so end up contributing less and getting paid less. Ergonarchy’s best friend being Market Forces.

And thus it will continue until society gets Ergonarchy under control, by the drastic measure of accepting that men are fathers too, and inviting them on board as equal parents. On the day when the problem of the working father is talked about as often as is the problem of the working mother, we will be getting somewhere. All children have two parents, though you’d never think it.

I am not suggesting, you must understand, that mothers should stay home and look after the children. I don’t want them forced back into the kitchen, heaven forfend, for this is just another kind of loneliness, albeit temporary. I want my Ministry for Human Happiness to ensure mothers are out there doing half as many hours for twice as much money.

Evidence of continuing male prejudice against women comes from the fact that the female wage is persistently lower than the male wage: though in Britain the gap is smaller than in the rest of Europe. But it is not on the whole the villainy and prejudice of men that leads to this undoubted inequity: it is the fact that the majority of women end up with children, and choose to give them more attention than they do their jobs. Even when partnered, many back off when the time comes for promotion, deciding that time for a personal and emotional life is more valuable than earning more money. The part-time nurse does not take the job as full-time ward sister, the TV researcher turns down the job as producer, because if they move up the ladder, when would they ever get to see the kids. The piece-worker in the home stitches shoes at 50p a pair because she has an ill child and is open to exploitation – not because she is a woman but because she is human being with a baby, and has no other options open to her. The earning capacity of the lone father (a fast growing group), falls as drastically as does that of the mother, when loneness strikes. While every working woman who has a small child pays another woman less than her own market value to look after the child – and she must, or she can’t afford the job – how can equality of wages be achieved? What meaning does ‘equal opportunities’ have, other than for the childless woman? If the statistics which told us about our comparative earnings made a distinction not just between men and women, but between men, childed women and unchilded women, we would begin to get somewhere – but they don’t. All women come under one heading. The fact that we do so well in the European league table suggests to me not that we’re moving towards gender equality, but that we have too many tired and overworked women with children amongst us.

We are barking up a dangerous and creaky old-fashioned seventies tree, when we go on struggling for equal wages, with the ardent encouragement of the government, when we would be better occupied turning men into resident and supporting fathers, instead of dismissing them from the case and saying, ‘Which way to the sperm bank?’ or, ‘How dare you treat me like this,’ or, ‘Oh I can manage alone and anyway there’s always the CSA, not to mention benefits. What makes you think I need a man?’

These days we tend to call our employment our ‘career’ and not our ‘job’. A career is something in which you compete with your colleagues for promotion, must be sharper and faster and harder working than they are, and put in longer hours. Thus we are divided and ruled, by big bosses so well hidden in the bureaucratic undergrowth it is next to impossible to fight them, let alone detect them.

There is no-one around these days to protect the employee – except now perhaps legislation out of Europe, for which God, male or female, be thanked. In the big State organisations – health, education, local government – accountants rule. Their duty is to cut costs and save the tax-payer’s money. So for the employee it’s all downgrading and re-writing of contracts, and here’s your redundancy money if you argue. The big companies look after the interests of share-holders first, customers second and employees last if at all. And the individual employer profits out of your skill and labour and always has but at least he’s around to meet your eye.

This Garden of Eden of ours is still open to Marxist interpretation, even in this the Age of Therapy.

Adam and Eve and pinch me

Went down to the river to bathe,

Adam and Eve were drowned,

And who do you think was saved?

Pinch Me, says the innocent child, and everyone runs round the playground screaming. Well, that’s how it used to be. The New Adam and the New Eve know better than to drown in the river, and the children’s playgrounds no longer ring with traditional rhymes: playtimes get shorter, and holidays too, as the schools adjust their working hours to the offices and not the other way round. The New Adam and the New Eve, victim of the Ergonarchy, have no time left to go down to the river and stand and stare, and contemplate the marvel of creation.

The New Adam, I say, and the New Eve. We are not what we were. Our instincts may lead us in the same old direction: our rational understanding leads us in another. Four things happened in the middle of the twentieth century to change our gender relationships profoundly and for ever, so that our nature and our nurture are no longer at peace. We’re just not used to it. The first two events are to do with medicine, the third to do with that powerful revolutionary idea, feminism, and the fourth to do with our new technological society. These are converging dynamics: you can’t have one without the other, like love and marriage back in the fifties. That was when we managed a marriage rate of nearly ninety percent, and the majority of those marriages were permanent. It can be managed.

The first event was female access to contraception. At the beginning of the century, as I say, contraception was illegal: it offended the Church – the flow of souls to God had to be maintained: it offended the State – whose need was for labour in time of peace and cannon-fodder in time of war. The convenience of authority sheltered, as ever, under the cloak of morality. From the sixties on, with the advent of the pill, gruesome in its early workings as it was, men no longer controlled female fertility. Sex was no longer intricately bound up with procreation: it could, and did, become recreational. A world outbreak of permissiveness, as we called it, with some relish. To have sex, in the New Age, you didn’t have to be married. And to be married, you didn’t have to have babies. Though it took a decade or so for people to get used to the idea, and the change to show through in the family-fragmentation statistics. But almost overnight men lost their traditional role, creator and protector of the family. The majority of men had lived up to their former responsibility very well. By and large, pre the nineteen-sixties, if you made a girl pregnant, you married her, and you looked after her and the child. Abortion was illegal, the world wasn’t set up for women to support themselves, and there were no State Benefits: other than that the State provided orphanages for abandoned children. Oddly enough, the moral censure thrown at the lone mother is greater today than it was back in the fifties, or that at least was my experience. Rash you may have been: lovelorn or deceived you probably were, and the consequences were dire enough without others feeling they had to join in, in condemnation.

The second great change is this. For the first time in history we have a preponderance of young men in our population. Young women are, believe it or not, in short supply. More men are always born than women – in this country it’s about one hundred and four males to every hundred females. But once upon a time illness, war and accident so sharply cut down the numbers of young men they were outnumbered by young women and so had a buyer’s market amongst them. It was they who picked and chose and women who did their best to attract. But young male life is safer now, thanks to medical care, the unfashionableness of war, and the trauma wards – and these days in all age groups up to forty-five men increasingly outnumber women: after that age the genders level-step until sixty or so, and with advancing age and man’s shorter lifespan, women once again begin to predominate. Today’s young woman does the sexual picking and choosing: she has the power to reject and uses it no better than the young man ever did. Women discover the gender triumphalism that once was the male’s preserve. See it in the ads. One for Peugeot at the moment: a brisk, beautiful, powerful young woman, followed by her droopy husband. She’s saying to the salesman, ‘It moves faster and it drinks less! Can they do the same for husbands?’ Try role-reversing that one! Does it matter? I suspect it does. It deprives men of their dignity: we all grow into what we are expected to be: this is the process of socialisation. Once women were indeed the little squeaky helpless domestic creatures the culture expected them to be. If we expect men to be laddish and appalling, that is how they will turn out. Where once it was the female fear that she might be left on the shelf, now, as young women get so picky, it is the man’s. We see the arrival of the men’s magazine: in which are discussed the arts of laddishness, flirtation, temptation, seduction: higher up the scale of sophistication, man as father, man as victim, man as sexual partner, man as cook. The way to a career woman’s heart is through her need for someone to do the childcare and the housework. Men are from Mars and women are from Venus but the space ships still need to flit between. Of course we are confused: courtship rituals are reversed. We have no traditions to fall back upon because tradition no longer applies. Poor us.

The third great change came with the seventies wave of feminism, when the personal became the political. In the course of writing a novel ‘Big’ Women (as opposed to ‘Little’ Women), in which I charted in fictional form the course of the feminist revolution, its causes, its progress, and its results. I came to realise the extent of the change we have lived through: to understand how difficult it is to see the wood for the trees.

The novel opens with two young women putting up a poster. A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle. Outrageous and baffling at the time, it turned out to be true. That is to say, she didn’t need one at all. The world has changed, the laws have changed; our young woman is out into the world. She may be lonely at night sometimes but she has her freedom and her financial independence. She can earn, she can spend, she can party. She can choose her sexual partners, but is not likely to stick with them: somehow she outranks them. And she knows well enough that if she has a baby all this will end. And so, increasingly, she chooses not to. The fertility rate, 3:5 in 1901, is now down to 1:8 and falling, below replacement level. Which may be okay for the future of the universe, but isn’t good news for the nation. We lose our brightest and best.

And the fourth thing that happened was that in the last fifty years we stopped being an industrial nation and turned into a service economy, and male muscle became irrelevant. I remember the days when they said women would never work on camera crews because of the weight of the equipment. Now there’s the digital Sony camcorder. Put it in the palm of your hand, your tiny hand, no longer frozen. Anyone can use it.

Adam and Eve and Tony Blair, we all have a lot to cope with. And Pinch Me’s always hiding just around the corner, of course, waiting to spring: changing his form all the time, like the Greek god Proteus, to avoid having to tell us the future.

On being asked by the Features Editor of The Daily Telegraph to write a piece, in the wake of the Countryside March, in the early spring of 1998, to defend the city against the country.

Behind the Rural Myth (#uc174d3d3-0008-5304-a19f-90f94caa4c16)

The countryside is pretty.

It’s pretty because there are so few people in it. There are so few people in it because there are so few jobs in it. And that’s the nub of the matter.

Yes, you can have a mobile office. Anyone can work from home in these the days of the computer, e-mail, fax, phone and scanner. Who needs the soap-opera of office life? Who wouldn’t want green trees not concrete the other side of the window. So move out. Except it’s insanity, isn’t it? For aloneness, read loneliness. And the blinds stay down to keep the sun off the computer screen. And when the crunch comes you’re the first to go. If the boss has never seen your face why should he bother about the look on it? And try getting the dole in the country: it’s so personal. They don’t just dosh it out like they do in the city: no, they read every word you’ve written on the form you’ve just filled in, and compare last week’s answers, and look everything up in the book – they’ve got time – and say no. And you don’t belong.

The countryside is relaxing.

Yes. You can tell from the clothes of the people who come up on the Countryside March. They don’t have many full-length mirrors in the country; countryfolk being either too haughty and grand to need them or else the ceilings are too low to fit them in. That must be it. The countryside’s not for the vain – heels sink into the mud, like the heels of little Gerda’s pretty red shoes in the Hans Christian Anderson story. Down and down they pulled her, ‘til she stood in the Hall of the Mud King. The countryside’s all practical woolly mufflers and crooked hems and garments it would be a wicked waste to throw out. The country’s full of good worthy people. A good girl in the city is a bad girl in the country. In the country the hairstylists like to turn you out looking like their mother. Well, they do that anywhere in the world, but you get the feeling in the country that they don’t like their mothers very much. Not that it matters; go out for the evening and the place is hardly jumping with film crews and flashbulbs. Who’s to see you?

The countryside is healthy.

No. It isn’t. But it’s unkind to go into that one. Let’s just say, organophosphates have made fools of us all. What goes onto the crops and what goes into the soil? We moved to the country once – kept a tranquil flock of rare-breed sheep which roamed our fields, in the most natural of natural ways. We fed them sheep nuts by hand. What was in the sheep nuts? Ground-up protein from more than one animal of origin. ‘Dip them!’ said the government. We built a trough and pushed the startled, innocent animals in, one by one, dripping and shaking and spluttering, nerve poison all over the place. Oh, thanks!

Pollution drifts over the countryside from the cities, lingers over the valleys. And the pollen count! Good Lord. Just listen to the countryside sneezing and wheezing. The cottage hospital closes. The trauma ward’s an hour away. People live longer in the cities.

And yet, and yet! I know. The warm glow of the setting sun on the old barn walls. The brilliant acid green of early spring. The blackness of night, the great vault of the firmament. The sense of a benign and fecund nature, of being part of the wheeling universe.

But what’s weakness, irrationality. Let’s get back to the brisk facts of the matter.

The countryside is our heritage.

Fact is, it’s shrinking and shrinking fast: suburbia creeps out from the towns. Forty-one percent of British marriages end in divorce, and rising. Twenty-eight percent of us live in single-person households, and rising. We have to build houses and build we do. No choice. And where are the bus services to get us to work, from our new ‘countryside estates’? Not down our road, that’s for sure. And work still stays in the city, so travel we must, and travel we do, and use the car, and know every radio presenter by heart. The countryside becomes somewhere to go, not somewhere to be. A car park here, a car park there: this way the castle, that way the old oak tree, and a fast-food snack as you go! Oh, goodbye, countryside. What rats we are, to leave the sinking ship!

You’re not cut off when you move to the country. Friends will visit.