скачать книгу бесплатно

As I’ve looked through mounds of my cuttings while writing this book, I’ve been struck by just how much I did. I only kept sparse notes of key conversations and cuttings of which I was particularly proud. I have a strong – my friends say nerdish – memory for the minutiae of the major political events in which I was involved, but in my trawl of the files I have come across stories under my byline and trips to the other side of the world which had temporarily gone from the memory.

Political journalism has changed in my years, as I explain later. Television has taken over from the House of Commons as the cockpit of political debate. Power has shifted from Westminster to the television studios, to Europe and to Scotland. But my successors need have no fear. There will always be a need for journalists to work and watch closely as politicians exercise their power.

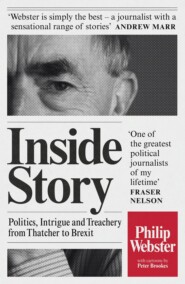

My story is of one journalist who stuck with the same paper, the one he had always dreamt of working on, and resisted the occasional blandishments of rival editors who told him his career would progress faster if he moved over to them.

This book is about the story behind the stories that ran across the front pages of The Times for four and more decades. There were serious, tragic, sad, dramatic and traumatic moments behind those stories. But chasing them and writing them was a great joy and privilege.

I start with the momentous events of 23 June 2016 that changed all our lives, finished off another prime minister, split the country in two and left British politics in utter turmoil.

A Nervous Breakdown as Britain Votes ‘Out’ (#ufdb0f7bc-4d58-5703-ade6-3b0b94778cb3)

A much-diminished David Cameron said an emotional farewell to the twenty-seven other heads of European governments in Brussels on 28 June 2016. It was a sombre occasion for the man who will go down in history as the leader who took Britain out of the European Union, and possibly broke up the United Kingdom. Five days earlier a chastened Cameron, along with George Osborne, his chancellor, watched their dreams turn to dust as Britain voted against their wishes, and the odds, to say goodbye to Brussels.

As the leader who gambled on a referendum that the country was not demanding at the time he announced it, Cameron knew that it was his fault. Within three hours of the final result he stood on the steps of 10 Downing Street and resigned. He was gone three weeks later. Osborne’s chances of succeeding Cameron, already slim because he was felt to have overstated his economic warnings during the referendum campaign, disappeared. He was not a candidate in the leadership election that followed. And his humiliation was not complete.

On the day of the vote, Cameron and his aides, and Osborne, had discussed what would happen if they lost, although at that time they were expecting to win. The chancellor, I was told, said there was a case for Cameron staying on to bring stability, as well as one for him going. Cameron was adamant that he must depart in those circumstances and his aides did not try to dissuade him. He went to bed for a few hours after the result became known; his mind was made up. Twenty days later – after a vicious but truncated leadership election – he was succeeded by Theresa May, who became Britain’s second woman prime minister at the age of fifty-nine.

Within hours she had stamped her authority with a ruthless reshuffle that saw few ministers stay in their jobs, and many of Cameron’s closest allies purged. Osborne was sacked, as was Michael Gove, the justice secretary. The ‘chumocracy’, the name given by detractors to the tight group of friends around Cameron which was reputed to take most government decisions, was brutally slain.

Britain woke up on 24 June, the morning after the referendum, a divided nation. We were a country split between young and old, better off and poor, north and south. The young, rich and parts of the south, particularly London, had voted ‘In’. The old, the angry and disadvantaged, and the north, had voted ‘Out’.

The kingdom was divided, with Scotland and Northern Ireland voting to stay in the EU, England and Wales opting for out. Nicola Sturgeon, leader of the Scottish National Party, said a second referendum on independence was highly likely. Scotland could leave the UK within years, and Brexit, as our departure will forever be known, will be to blame.

Apart from the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), the irrepressible Nigel Farage – whose referendum and victory it was – few of the leaders of the ‘Leave’ campaign offered outward signs of jubilation. They had not expected to win, and secretly many had probably hoped they would not. Many who had voted to leave wondered what they had done. Some recanted on the airwaves within hours. It was too late. Out was out.

In the days that followed, British politics descended into a form of insanity. The two men who had led the campaign to leave, Boris Johnson (the former London mayor) and Michael Gove, killed each other’s chances of leading their party – the latter accused of committing an act of treachery without parallel in modern political history; Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, was pushed to the brink of resigning from his party; Farage stood down in triumph, his job done; and for a few days it looked as if the country was running without a government or opposition.

Andrea Leadsom, the energy minister who became the main Brexit candidate as Johnson and Gove fell away, was chosen by MPs to go into a run-off with Theresa May. But then she stunned an already shell-shocked Westminster by suddenly withdrawing only an hour after May formally launched her campaign, leaving the home secretary the victor without the need for an election by party members. After starting her own campaign, Leadsom had suffered a torrid weekend, fiercely criticized by the Conservative press and MPs after claims that she had exaggerated her CV, questions over her tax return, and an interview with The Times in which she appeared to suggest that as a mother she had an advantage over the childless May.

The rest of Europe, and much of the world, looked on in horror and amazement. The Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, not known for hyperbole, suggested: ‘England has collapsed politically, monetarily, constitutionally and economically.’

The bloodletting was by no means over, and the twists and turns in this fast-moving epic continued. First May called in Osborne and told him she needed a new chancellor after using her leadership campaign to distance herself from his economic stance. As the principal architect of ‘Project Fear’, the name given to the torrent of gruesome economic warnings that emanated from the Treasury during the campaign, and which was felt to have backfired, he harboured little hope of surviving.

Then she revived Johnson’s tottering career by making him foreign secretary. She had texted him expressing sympathy on the morning when he had been suddenly deserted by Gove. Boris claimed to be ‘humbled’ and his elevation surprised him and most of the political world, which had started to write him off.

The next morning May called in Gove, with whom she had sharply clashed in government, and sacked him as well in what friends called an ‘impeccably polite’ exchange. So Boris was in the Cabinet for the first time and Gove, who had struck him down just days earlier, was out.

Nicky Morgan, the education secretary who had made the mistake of backing Gove, was shown the door as well. The speed of events was startling and May, having watched a fortnight of political assassinations, proved to be a brutal axe-woman when her time came. In just forty-eight hours the old guard had retired from the fray, with Cameron and Osborne spotted having coffee in a Notting Hill cafe, and the new regime was in place.

Until 2016, Harold Macmillan’s ‘Night of the Long Knives’ in 1962, when the then prime minister ejected seven ministers from his Cabinet, was deemed the most ferocious exercise in prime ministerial power in history. No longer. May culled Cameron’s team and sent nine of them to the back-benches. Cabinet executions are normally done by telephone. But May looked them in the eye as she did it. Her aides said it was a matter of courtesy, but some of the victims wished they had not been put through the ordeal. She even gave Gove a lecture in loyalty as she despatched him. May had shown herself to be fearless and not a leader to be messed with. But her Commons majority is tiny and one day she may regret making so many enemies in one fell swoop.

The nervous breakdown that gripped Westminster overshadowed the gravity of the decision that Britain had taken and the mess that the departed leaders had left for others to clear up. Yes, Britain now had a new prime minister. But this was of much less significance than what else had happened. After forty-three years, the United Kingdom was cut adrift from the organization with which it had always lived uneasily but which, until the referendum dawned, people had seemed prepared to accept.

Now we were on the outside, and the nation was in shock, most not having expected the outcome even if they voted for it. The pound slumped to its lowest level in a generation, firms voiced doubts about investing here, young people marched on Parliament complaining that their futures had been compromised by what they called the lies of the ‘Leave’ campaign, and Osborne was forced to drop his plan to take the economy into surplus by 2020. At the same time, there was a disturbing rise in racially motivated attacks, with Polish and other migrants saying they no longer felt welcome.

Europe had killed another prime minister. But far more important than that, the vote had left Britain with a deeply uncertain future, facing at least two years of negotiations about its relationship with the body it had abandoned.

In truth it will be years before the full impact of cutting formal links with our biggest market can be assessed, but the Treasury is fully expecting a bleak 2017, and the outlook for future years is not much better. A friend said of Osborne: ‘George fears that an awful lot of hard work by the country and us has gone up in smoke.’

This is a chronicle of events in a nutshell. The details, however, bear much closer examination.

I have known Boris Johnson and Michael Gove for years. I remember little of Boris’s brief spell on The Times as a young reporter, but got to know him pretty well on my regular trips to European summits when he was the Brussels chief for The Daily Telegraph. I knew Michael well from his time as comment editor and news editor at The Times, when we would have several conversations every day about the political stories of the moment.

I got on very well with both of them but neither I nor anyone who worked with them could have dreamt that one day they would have the destiny of the nation in their hands. Boris made us laugh and was wonderfully indecisive, as I describe in a later chapter. Govey, as many in the office called him, was bookish, polite, deeply knowledgeable about politics, humorous. We knew that Gove, a Conservative, was looking for a parliamentary seat. But political leaders? It never occurred to us.

Yet here they were, on the morning of 24 June, squinting into the cameras, speaking in hushed, statesmanlike tones about the seriousness of the decision that had been taken. They together had been the public face – along with Farage – of the ‘Leave’ campaign. And here on the dawn of victory it was obvious they had no idea what would happen next. That ignorance was shared by most of the rest of the Government. As the markets tumbled, and as recriminations broke out between the rival campaigns, government came to a stop and it was clear that there had been little planning for a Brexit outcome.

As the Government floundered, Her Majesty’s Opposition fell apart. The campaign to stay in the EU, dubbed ‘Remain’, lost because millions of traditional Labour supporters in its heartlands voted to leave, rebelling at last at what they saw as a southern elite telling them what was good for them and failing to heed their worries about excessive immigration. Many saw themselves as the victims of what the southerners called globalization and what they saw as foreigners taking their jobs.

Labour was distraught because as a party it was strongly in favour of staying in. But Jeremy Corbyn had a long history of animosity towards the EU and was felt at best not to have pulled his weight during the campaign and at worst to have allowed his hard-left aides to undermine it. His shadow Cabinet and front-bench walked out on him, a motion of no confidence was easily passed against him, and senior figures dithered over challenging him. He refused to step down and vowed to fight on. Angela Eagle, shadow business secretary and shadow first secretary, who had excelled during the previous year when standing in for Corbyn at PM’s Questions, announced she was running but then pulled out, leaving Owen Smith, former shadow work and pensions secretary and an MP for only six years, to take on Corbyn. A leadership contest – for the second summer in succession – was under way as this book went to the printers.

Within a week of the referendum the Tory party was in complete chaos. Johnson was briefly and magically transformed from the assassin of the Prime Minister into the unity candidate best able to uphold the values of liberal Conservatism. Gove promised to be his campaign manager for what looked likely to be a relatively straightforward victory. We should have known, however, that nothing is simple in the Tory party.

Gove, his campaign team, and his wife, the journalist Sarah Vine, began – according to their side of the story – to have doubts about Johnson’s ability to be prime minister, leading Gove, just a week after the vote, to withdraw support from Johnson, announce he was standing himself and decry the leadership qualities of his friend and colleague.

The betrayal stunned Johnson, who swiftly pulled out, leaving May, the home secretary, the clear favourite, and his team went to war on Gove. One suggested there was a ‘deep pit reserved in hell’ for Gove, Johnson’s sister Rachel accused Gove of being a political psychopath, and Ben Wallace, another Johnson campaign aide, said Gove could not be trusted to be prime minister because he has ‘an emotional need to gossip, particularly when drink is taken, as it all too often seemed to be’. The governing party was in turmoil.

How did the two men who had done more than any, apart from Farage, to bring Brexit about fall out so spectacularly and so quickly?

Friends told me that Johnson had asked Gove to be his campaign manager on the Friday after the vote. Gove asked for twenty-four hours to think it over and was approached by several colleagues to run. He pointed out that he had always said he did not want to be prime minister and felt that Boris was the man.

Gove’s friends said that, although he had known Boris for twenty years, he had never worked closely with him. Johnson had risen to the occasion during the campaign and Gove assumed he was ready for the top job. But that confidence was to be swiftly shattered. According to friends, he found that Johnson had only a ramshackle leadership campaign operation in place and did not appear to be taking seriously the coming moment when he switched from the populist ex-mayor liked by the voters to the serious job of prime minister. Little work had been done on setting out a programme or vision for leadership.

For three days Gove campaigned for Johnson, growing more and more concerned that he seemed unfocused on the task in hand. For Boris, it was vital to have Andrea Leadsom, who had won plaudits for her role during the referendum campaign, on board. I have learnt that on the morning of Wednesday, 29 June, an astonishing meeting took place in a Commons office. Three of the leaders of the Brexit cause met privately to discuss what jobs would be allocated if Johnson won.

They were Johnson, Gove and Leadsom. The latter, at the time an energy minister, asked to be chancellor in return for supporting Johnson. Gove pointed out there were two top jobs, the other being deputy prime minister, who would also have the job of running the negotiations with the EU on Brexit. Leadsom said she assumed Gove would do the latter job but Johnson said he wanted Gove to be chancellor. Finally it was agreed that Leadsom would have one of the top jobs and that Johnson would make this clear in a letter, and send out a tweet saying that Leadsom was on board with his campaign.

As has been revealed since, the letter did not reach Leadsom by the time she had stipulated and the tweet did not materialize. As a result she prepared to announce that she would stand, having already built up a serious level of support among MPs. That Wednesday, Johnson was also supposed to be writing his launch speech for the next day, but by midnight he had scarcely done any of it. The Leadsom fiasco and the failure to prepare were two last straws.

Gove and other figures like Nick Boles, the skills minister, were dismayed, and Gove finally decided that Johnson did not have the qualities to be prime minister. He told allies: ‘I could not in those circumstances bring myself to recommend to my friends and fellow MPs that Boris was suitable to be PM. When Gordon Brown was about to become prime minister a lot of senior people believed he would not be up to it but stayed silent. I could not do that. I had to be honest about what I saw as Boris’s failings.’

Gove then announced he would stand, and within minutes Johnson, appearing at what would have been his launch, pulled out, stunning his supporters in the audience who had not been forewarned.

Gove was surprised. He had expected Johnson to stay in the race and to tell him (Gove) that he would show him that he was good enough, friends said. May, who had a long-running dispute with Johnson when he was mayor when she opposed the use of water cannon on the streets of the capital, had barely launched her campaign when she learnt her long-time foe was out of the race.

As the carnage continued, Johnson backed Leadsom, stressing her trustworthiness in what was clearly a rebuke to Gove. Johnson’s team claimed that Gove had planned his desertion all along and that he had used their man to get the Brexit result and then stabbed him in the back and front, while running over him at the same time. That is denied by Gove’s team, who point to his constant disavowals of interest in the job.

After the first round of voting May was ahead, with Leadsom second and Gove third, his standing obviously harmed by his treatment of Johnson and Johnson’s decision to fall in behind Leadsom. Then came another twist. Boles quietly approached figures in the May campaign and asked if they could ‘lend’ Gove some votes so that he could finish second in the next ballot and keep Leadsom out of the final two-way run-off which would be decided by some 150,000 party members and not the MPs.

May would hear none of it and one of her team, I understand, told Boles that she was ‘going for gold’ and believed that the higher the number of MPs backing her, the greater her chance of defeating Leadsom or Gove, whoever came second. So Boles embarked on an extraordinary freelance operation which probably cost Gove any chance of making the final two.

Boles sent an e-mail to ten friends in the May camp suggesting there was a risk that if Leadsom’s name went through, members might back her because she shared their attitudes to modern life. He added that Gove would not mind taking a ‘good thrashing’ for May in the party’s interest.

By now the political world was immune to shocks in this astonishing saga but the Boles e-mail – which was leaked by a disaffected recipient and swiftly made public by Sam Coates of The Times – took a prize for infamy. Gove, having stopped Boris, was now it seemed prepared to go to any lengths to kill Leadsom’s hopes. This was unfair because Boles did not tell Gove about his manoeuvre. But the damage was done – and fatally.

I reproduce the e-mail in full. It said:

I would be really grateful if you would treat this in strict confidence. You are my friend. I respect the fact that you want Theresa May to be PM. It is overwhelmingly likely that she will be. And if she does I will sleep easily at night.

But I am seriously frightened about the risk of allowing Andrea Leadsom onto the membership ballot. What if Theresa stumbles? Are we really confident that the membership won’t vote for a fresh face who shares their attitudes about much of modern life? Like they did with IDS.

I am not asking you to respond unless you positively want to have a chat. But I hope that you will reflect on this carefully. Michael doesn’t mind spending 2 months taking a good thrashing from Theresa if that’s what it takes but in the party’s interest and the national interest surely we must work together to stop AL? x

Gove had stabbed Johnson, Boris had stabbed Gove, Gove’s friends had tried to stab Andrea. There were times during this period when an hour seemed a long time in politics.

Leadsom finished second in the next ballot and Gove was eliminated. Members were left with a choice between May’s substantial experience, including six years as home secretary, and her cautious but modern conservatism – it was she who first told the party to throw off its ‘nasty’ image – and Leadsom’s appeal to the party’s traditional core values: self-reliance, dislike of regulation, suspicion of social change such as same-sex marriage, and deep Euroscepticism.

The run-off began no less controversially than the early legs of the contest. Leadsom received a barrage of attacks after her ‘motherhood’ remarks to The Times on 9 July 2016. She was criticized by MPs for her lack of experience and naivety. Then on Monday, 11 July, just as May was officially launching her campaign in Birmingham and Cameron was speaking at the Farnborough air show, word emerged that Leadsom had had enough.

Surrounded by her supporters, she came out of her house and said she had decided to withdraw. Although she had won the backing of eighty-four MPs, she said that this was less than twenty-five per cent of the total, which was not enough to lead a strong and stable government if she won the ballot of members. She departed saying it was in the best interests of the country and party that she was no longer a candidate. She made no mention of her notorious interview but she had already apologized to May over it and her friends later spoke of the ‘brutal’ way she had been treated. They added that the contest had come too soon for her and that she had never expected to run.

So eighteen days after Cameron said he was leaving the stage, the three most prominent leaders of the Brexit campaign had been vanquished, their ambitions at best put on hold and at worst killed. They had handed the keys of Number 10 to a minister who had campaigned to stay in the EU.

Now May’s main task was to handle the consequences of that fateful vote. ‘Brexit means Brexit and we are going to make a success of it,’ she said at her launch. Quite what Brexit really means will only become clear in the years ahead, but on one thing May was clear: ‘There will be no attempt to remain in the EU.’

May, though, made plain that she is determined to get the best possible deal for Britain from the negotiations that will set the terms of departure.

She put the astute and pragmatic David Davis, a former Europe minister, in charge of a new department that will implement Brexit. Though he and Johnson backed the ‘Leave’ effort, neither are ideologically ‘anti-Europe’ and May is clearly hoping they can secure an outcome that will maintain some kind of access from outside to the single market while securing concessions on freedom of movement. It may take years.

I covered the removal of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister, as I describe later in this book. Whatever you felt about her, Thatcher’s downfall was a personal tragedy, a Shakespearean drama as the MPs and ministers she had helped to three election victories turned on her because they felt she could not win a fourth. June 2016 was a personal tragedy for Cameron. Whether the nation will regret or embrace the outcome in the long term is impossible to tell. But the aftermath at the top of the Conservative Party seemed at times more like farce than tragedy.

How could it have come to this? How could David Cameron, the man who told his party to stop banging on about Europe, have somehow contrived to take his country out of it? How was it that the PM who earned a reputation as a lucky general ran out of luck when it mattered most?

The story begins with his party’s recent history. Cameron became party leader after he wowed the party faithful in 2005. But his MPs were never as certain about him as his activists were. They were unsure about his efforts to modernize the Tories but went along with him in the expectation that he would see off Gordon Brown easily in 2010 and return them to power. He became prime minister, yes, but only in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, and his half-victory left many MPs disappointed with him.

23 January 2013 was the day that sealed the fate of Cameron, many in his government and the country. He announced there would be an ‘in-out’ referendum by the end of 2017 at the latest. In October 2011 some eighty-one Tory MPs had demanded a referendum in a Commons vote, showing him the scale of the internal problem he faced. UKIP was on the march, winning the European elections in 2014 while two Tory MPs were to defect and win by-elections under the UKIP banner.

Cameron had agonized discussions with his Cabinet, in private one-on-one conversations and together. I can confirm that both George Osborne and Michael Gove urged him not to do it, Osborne because he feared the country might vote to leave, and Gove because, as a devout sceptic, he could see himself ending up fighting his friend and prime minister.

In an e-mail to Cameron, Gove warned that if he granted a referendum it would not bring peace to the party and that he would continue to be ‘harried’, and that it was dangerous to commit to a plebiscite before it was known what reforms Europe would offer up. Gove, at this stage, did not explicitly say to Cameron that he would campaign against him, but the PM could have been in no doubt about his deep concerns.

As the negotiations with Brussels reached their climax in the winter of 2015, Cameron several times asked Gove’s friends – including Osborne, Ed Vaizey (culture minister) and Nick Boles – whether Gove would be ‘all right’ when the time came. But it was clear from a number of newspaper stories since the party conference in October that Gove was likely to be in the opposite camp and that he was ‘conflicted’ about opposing his friend the prime minister.

As Cameron prepared to announce the referendum date on Saturday, 20 February, Ed Llewellyn (his chief of staff) approached Gove and told him Downing Street needed to know that he would be on side in view of the extensive media coverage the coming weekend. Gove told him that he could not be and would campaign in line with his long-stated beliefs. It was a big blow to Cameron.

Cameron himself confirmed the news publicly: ‘Michael is one of my oldest and closest friends but he has wanted to get Britain to pull out of the EU for about thirty years,’ he said. ‘So of course I am disappointed that we are not going to be on the same side as we have this vital argument about our country’s future. I am disappointed but I am not surprised.’

Gove said:

It pains me to have to disagree with the Prime Minister on any issue. My instinct is to support him through good times and bad.

But I cannot duck the choice which the Prime Minister has given every one of us. In a few months’ time we will all have the opportunity to decide whether Britain should stay in the European Union or leave. I believe our country would be freer, fairer and better off outside the EU. And if, at this moment of decision, I didn’t say what I believe I would not be true to my convictions or my country.

Johnson and Gove had dined together and agreed that a late initiative by Oliver Letwin, the Cabinet Office minister and Cameron’s close adviser, to change the Act authorizing the UK’s accession to the EU to bolster the UK’s parliamentary sovereignty was not sufficient to assuage their doubts, but Gove was as much in the dark as Cameron about what Johnson would decide. He only learnt that he was to be in the Brexit camp on the Saturday afternoon before Johnson made his announcement on Sunday, 21 February.

After winning what most considered an underwhelming renegotiation package, Cameron had bitten the bullet and announced 23 June as the day of decision. He had gone for the fastest-possible timetable, rejecting the advice of his strategist, Lynton Crosby, who warned that it could turn into a protest vote.

Cameron had hoped to persuade Johnson to come on side, and at a forty-minute meeting in Number 10 the previous week, he offered him various posts in the coming reshuffle. The former mayor was undecided until the very last minute. When he did declare, Cameron and others accused him of doing so for opportunistic reasons of self-advancement. There can be little doubt that he did it because he saw it as a way eventually of taking Cameron’s job.

I learn there were few tears in Downing Street when Gove plunged the knife into Johnson, although Cameron believed that Gove’s behaviour would win sympathy in the party for Johnson. Gove earned the displeasure of Cameron and close friends for campaigning with vigour for Brexit. They had hoped and believed he would play a low-key role. Gove’s position was known but Cameron had not expected his erstwhile friend – the atmosphere between them now as I write this is glacial, according to an insider – to campaign so strongly and, he felt, personally against him.

As was widely reported, Cameron’s wife, Samantha, had a stand-up row with Gove’s wife, Sarah Vine, at a friend’s party, accusing Gove of betrayal and abandoning her husband’s premiership. Other friendships and family relationships across the country were similarly strained as the campaign developed into mud-slinging and bitterness. Gove told me after he had pulled out of the contest:

I did not relish being on the opposite side to David but it became clear to me during the course of the campaign that if it was going to be conducted in a professional way, I had to speak up for my beliefs. Having made the decision, I had to argue in the way I did. But I tried to make the case without personal attacks and on the basis of principle.

The warnings from Osborne and Gove were acutely prophetic but back in 2013, Cameron, the gambler, had had enough of the Tory Right, he was worried about UKIP and he thought that when the time came he could negotiate a good deal out of Brussels and win. Cameron’s aides and supporters believed that he had no choice and that the time to settle the issue had come. One told me after 23 June: ‘There really was little alternative. The political pressure was unstoppable.’

But it has to be said that Cameron called the referendum for party political reasons and not for the national interest. There was no clamour for it in the country and the decision was to blow up in his face and put the country on a deeply uncertain path.

I believe the referendum was a mistake. Cameron could not be sure of winning, and he lost. Thatcher once said that referendums ‘sacrificed parliamentary sovereignty to political expediency’ and most leaders hate them because voters do not necessarily use them to decide the issue in question but to make a protest. In this referendum, ‘Leave’ voters did so for all kinds of reasons. ‘Remain’ voters just voted to remain.

By the time he capitulated to the Right, Cameron had often been called the ‘essay-crisis’ PM, the leader who only turned his attention to problems at the last moment and then rushed through an answer to them. The referendum pledge helped him see off his own right wing and the threat of UKIP, and may well have helped him win outright in 2015. But the country was landed with a critical decision on its future and millions felt ill-equipped to make it.

Cameron’s second-biggest error was overconfidence. As recently as December 2015 he told his European colleagues that he was a winner and they should not worry too much. His serendipity may have led to him accepting a deal from Brussels that was not good enough, and once the campaign was under way he did not use all the weapons available to him, as I will explain.

In March 2016, Cameron’s campaign was abruptly thrown off course by an event that he should have anticipated but did not. Two days after the 2016 Budget, Iain Duncan Smith, the work and pensions secretary, resigned. The immediate issue was cuts to disability benefits. The reason was George Osborne.

Osborne and the man in charge of the biggest government budget did not get on. IDS had row after row with the chancellor over his repeated attempts to cut benefits for working people as his main weapon to tackle the deficit. I understand the resignation had been brewing since January 2014, when Osborne announced he would make a further £12 billion of cuts in welfare in the next parliament. He had not discussed the plan with IDS. ‘It was a bounce,’ he has since told friends.

We know that Osborne did not have a high opinion of his colleague. As Matthew D’Ancona told us in his book In It Together: ‘“He opposes every cut,” Osborne complained to one friend.’ Nor was he confident that IDS had the IQ. ‘You see Iain giving presentations,’ he confided in allies, ‘and realize he’s just not clever enough.’ IDS, I learnt, has no higher opinion of the ex-chancellor. A friend said: ‘Iain regards George as arrogant. He is not collegiate. He lands the government in one shambles after another by his refusal to consult. He fancies himself as the master strategist. His record does not justify such pride.’ Another friend said: ‘Iain does not like George or his cronies. He encroaches on everyone’s pitch. He is mad for a headline – so in the 2016 Budget we got his great announcement that all schools would have to become academies. Then six weeks later poor old Nicky Morgan [former education secretary] had to retreat. It is one omnishambles after another.’

That was a reference to Osborne’s 2012 Budget when what seemed like a decent package on the day collapsed quickly with retreat after retreat on matters such as taxes on Cornish pasties and caravans. It became known as the ‘Omnishambles Budget’.

But when, on the early evening of 18 March 2016, Downing Street received a letter from IDS resigning over the disability cuts, a shocked Cameron realized this was deadly dangerous to him. He called IDS, asking him to hold off until they had spoken face to face. Soon government sources were briefing that the £1.3 billion cuts were being ‘reviewed’.

But IDS had had enough, and in a second telephone call told Cameron his mind was made up. During furious exchanges, Cameron was reported to have called IDS a ‘shit’, something that neither side has seen fit to deny. Duncan Smith’s friends maintain he had been surprised by Osborne’s decision to put the cuts in the Budget so that they could be counted as billions of savings in the deficit battle, but that the last straw was to put them in the same package as tax cuts for the better off. ‘It went against Iain’s whole social justice message, and he had to go,’ an insider said.

IDS had been in constant rows with Osborne over the previous six months about the chancellor’s plan to cut tax credits for three million people, eventually defeated by the Lords and dropped, and the IDS plan to merge several benefits into a universal credit. One friend said: ‘Iain regrets not going earlier. He thought about resigning before Christmas 2015 and wishes he had. He tried to defend the Budget but lost heart and realized he could not in all honesty do so.’

IDS, for decades an opponent of the European Union, has insisted since that his resignation had nothing to do with Europe, and he stayed out of the campaign for a few weeks to show that. But his enemies maintained that the whole exercise was designed to damage Cameron and Osborne at a time when they could least afford it. Some claimed that IDS had planned to quit the Government dramatically during the Budget debate, something his friends have denied.

I can confirm, however, that he was one of several ministers who called on Cameron privately earlier in the year to allow ministers freedom to speak out during the referendum campaign. IDS told him that if he did not grant the concession, ministers would resign and that would be far more damaging to the Government. I understand that the key figure in persuading the PM to give way – much to the unease of key pro-Europeans like Michael Heseltine – was Chris Grayling, leader of the House of Commons.

By the end of 2015, Grayling had concluded that the deal the Prime Minister had been negotiating with Europe would not be good enough to change his view that Britain would be better off out. He decided that he would campaign to leave but delayed until the New Year before telling Cameron. After the regular 8.30 a.m. meeting of ministers, aides and Commons business managers on Monday, 5 January, Grayling stayed on for a private chat with the PM. He told him that he intended to campaign for an ‘Out’ vote and offered to resign. On the same day, Theresa Villiers, the Northern Ireland secretary, had a similar conversation.

Cameron had been moving towards allowing ministerial freedom as Harold Wilson had for Labour ministers in the 1975 referendum but he had not intended to announce it at this stage. While Grayling’s remarks were an offer to resign, Cameron would have seen them as a threat, and concluded that ministerial resignations would be more damaging than allowing them latitude. He may have concluded that keeping them inside the tent would avoid the more abrasive campaigning that would be inevitable if they were speaking from outside the Cabinet. He got that wrong. He was to be shocked by the interventions of Outers such as Gove, Johnson, Leadsom and others.

So why in the end did Cameron lose a campaign that he believed from 2013 that he would win and win well?

As they gathered on the morning before referendum day there was cautious confidence – much more than there had been for some time – among the leaders of ‘Britain Stronger In Europe’, the official all-party campaign to remain in the EU.

Andrew Cooper (Lord Cooper of Windrush), the founder of the polling company Populus and director of strategy for David Cameron between 2011 and 2013, had for a few days been bringing better news to the gathering of Downing Street aides (including Craig Oliver, the communications chief) and Labour and Lib Dem strategists. Less than twenty-four hours before the polls opened the PM was told that he would win by several points.

But the late confidence was misplaced because Downing Street and other campaigners had underestimated the impact of immigration on the campaign and overestimated the impact of the economy. The Tories had won the 2015 election on the back of economic competence and thought they could do it again. There appears to have been a basic mistake in the so-called ‘playbook’ on which the campaign was based.

The previous summer, on the basis of a survey involving thousands of respondents, Populus presented the board of ‘Stronger In’ with a finding that suggested that the economy was massively more important than immigration to most voters. The conclusion was not challenged and treated as a fait accompli, according to campaign sources. It meant that from the moment Cameron fired the starting gun, warnings about the impact of a Brexit on the economy flowed from the mouths of Chancellor, Prime Minister, Bank of England Governor and any half-respectable think-tank or international body, with the President of the United States pitching in to suggest that Britain would drop to the back of the queue in the negotiation of post-Brexit trade deals. Little had been prepared on immigration.

The sheer ferocity of the warnings from George Osborne – he threatened an emergency Budget in the final days of the campaign – appears in the end to have been counter-productive, with ordinary voters accusing ministers of going over the top and not believing what they were told in any case.