Полная версия:

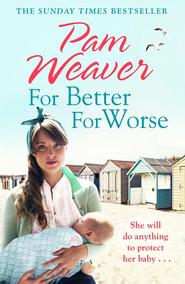

For Better For Worse

PAM WEAVER

For Better For Worse

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers in 2014

This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2017

Copyright © Pam Weaver 2014

Pam Weaver asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847563637

Ebook Edition © July 2014 ISBN: 9780007480456

Version: 2017-03-13

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Tony and Audrey Hindley and Polly McLelland. Thank you for all the times you’ve encouraged me. If they gave out medals for encouragers, you three would share the winner’s podium.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

One

July 1948

It was gone. Really gone. She’d spent the past hour hunting high and low for it, but it was no use. She couldn’t find it anywhere. She’d tried all the usual places first: the drawer, the kitchen dresser, her coat pocket, but she quickly drew a blank. She’d even been outside and looked down the street in the hope that it hadn’t fallen from her pocket, but she couldn’t see it. Her stomach was in knots. After everything else, this couldn’t be happening. Having tried the obvious places, for the past ten minutes she’d been looking in the pram, the toy box and the outside lav, places where she knew it couldn’t possibly be, and yet she hoped against hope that she’d find it.

‘Have you seen Mummy’s purse?’

Jenny pushed her silky brown hair out of her eyes and looked up at her mother with a blank expression. She was a pretty child with long eyelashes. Born in the middle of the war, she was Sarah’s first child.

‘My purse,’ Sarah said impatiently. ‘Have you taken it to play shops?’

‘Oh, Mummy,’ her daughter tutted, one hand on her hip and her mother’s scolding expression on her face, ‘I’m not playing shops. This is dolly’s tea party.’

Sarah frowned crossly. ‘Don’t get lippy with me, young lady. I asked you a question. Have you seen my purse?’

Her daughter looked suitably chastised. ‘No, Mummy.’

Sarah’s heart melted. She shouldn’t have spoken to her like that. She wasn’t having a good day either. Just an hour ago, Jenny had come into the shared kitchen with a worried frown. ‘Mummy, Goldie isn’t very well.’

Sarah had followed her back up to the bedroom and sure enough, her pet goldfish was floating on the top of the water. Slipping her arm around her daughter’s shoulder, Sarah had to explain that Goldie wasn’t ill; she had died and gone to heaven.

Jenny had stared at her mother, her wide eyes brimming with tears. ‘But why?’

Why indeed, thought Sarah. ‘It just happens, darling. Fish get old and die. It was Goldie’s time to go.’

‘Is that what happened to Daddy?’ Jenny’s words hung in the air like icicles and Sarah had swallowed hard. Her heartbeat quickened and she felt very uncomfortable. It was at that moment she realised she should have talked to her daughter before. She had no idea the poor little mite had been thinking that Henry was dead. ‘No, darling,’ she’d said, drawing her closer. ‘Daddy isn’t dead. Daddy went to live somewhere else.’

‘Why Mummy? Didn’t he like living with us?’

Sarah had taken in a silent breath, wondering how on earth she could answer that. She didn’t really understand herself, so how was she going to explain to a six-year-old why her father had simply packed his bags and walked out? Up until that moment she had thought Jenny was coping well. She’d seemed to accept that Henry had gone away, but as they’d talked Sarah could see that that Jenny hadn’t really understood after all.

‘I’m sure Daddy loved living with us,’ she’d said, kneeling down to look into Jenny’s face, ‘but he had to go away.’

Suddenly, Sarah’s youngest daughter Lu-Lu crashed into them and tried to kiss her big sister. Jenny laid her head on her mother’s shoulder. ‘Did it hurt?’

Sarah frowned. It was hard to follow the child’s reasoning. ‘Did what hurt?’

‘Did it hurt Goldie when she died?’

By now Sarah had drawn her arms around both her children. ‘No. I don’t think it did and I’m sure Goldie had a very happy life.’

Jenny had put her hands on the goldfish bowl. ‘Can we bury her?’

‘Of course,’ smiled Sarah. ‘I think I’ve got a little box we can put her in and we’ll bury her in the garden.’

They laid the fish on a bed of cotton wool inside a box which once held three man-sized handkerchiefs and Sarah put the lid on. Goldie was all ready for burial, but they couldn’t do it there and then. It was raining hard and Sarah didn’t have anything suitable for digging in their tiny courtyard garden so she promised Jenny they would bury the goldfish after school the next day.

‘Can I ask Carole to come to Goldie’s frunrel?’

Sarah hesitated. Her sister Vera made her feel that Henry’s disappearance was somehow her fault, and although Jenny and her cousin Carole got on well, she wasn’t too keen to have her sister around.

‘Please, Mummy. Please,’ Jenny pleaded.

Sarah nodded reluctantly. ‘I’ll talk to Auntie Vera,’ she promised.

It had brought a lump to her throat as she watched her daughter drawing a picture for Goldie, so she decided to give the girls a little treat. It was almost lunchtime, and the corner shop closed from 1 p.m. until 2 p.m. Sarah still had some coupons and if Mrs Rivers next door would take them in, she just had time to run and get some sweets.

Mrs Rivers was only too glad to have the girls. She was fond of Jenny and she loved spoiling Lu-Lu. Sarah had promised to be as quick as she could. She’d used her sweet ration for the first time in months to buy them a small bar of Cadbury’s each. Given their normal circumstances, it would have seemed extravagant, but with the guinea Mr Lovett had pushed into her hand, she told herself it was only 3d a bar and she knew the girls loved chocolate. The purse had been in her basket when she came out of the shop because she remembered stuffing it down the side. After that, she couldn’t remember seeing it again. She’d collected the girls and come home, so somewhere between the sweet shop, Mrs Rivers’ place and home, the purse had been lifted or dropped out of the basket. She shifted the pile of papers on the kitchen table. She’d already searched through them once but she was irresistibly drawn back to look yet again. The purse wasn’t there.

Lu-Lu toddled across the floor and sat down to eat a crumb which had fallen from the table. At fifteen months, everything went straight into her mouth. Sarah bent to take it from her hand before she put it in her mouth, and as she lowered herself back onto the chair, the terrible realisation dawned. Her purse with all her money in it was well and truly lost. What was she going to do? That purse contained the coal money and everything they had to live on for the next week. There was no nest egg to fall back on, no Post Office book with a secret stash, no money in the jar on the top of the dresser. She couldn’t ask her sister to help either. Since her brother-in-law had landed a job with Lancing Carriage Works, Vera had become rather sniffy. She’d been friendly enough when Sarah lived in the house in Littlehampton, but since she’d come to Worthing, Vera’s attitude had changed. If she didn’t know better, Sarah might have thought she was ashamed of her.

Lu-Lu asked to be picked up and Sarah pulled her onto her lap, kissing the top of her golden hair as she did so. Jenny had inherited her mother’s light brown hair and hazel eyes but Lu-Lu had blue eyes and fairer hair. Cuddling her daughter, Sarah shook all thoughts of Henry away. She felt the tears prick the backs of her eyes, but what was the use of crying? That never solved anything. She hadn’t cried when he’d buggered off and she wasn’t going to start now. Besides, it was no good going back over what might have been. That was all in the past and right now her most pressing problem was what to do about her missing purse. She didn’t have a lot before it went and now she had absolutely nothing. How was she going to manage? As a woman deserted, she had no widow’s allowance. Henry contributed nothing towards the care of his children. Every penny they had was what she earned. Thank God she’d already got the rent money together. That was tucked into the rent book on the dresser, but she still had the children to feed.

Their home was two rooms on the first floor of a run-down fisherman’s cottage in Worthing where they shared the downstairs kitchen and toilet with another tenant. They were just across the road from the sea, but being at the back of some larger buildings meant that there was little incentive for the landlord to improve the property. The old woman who lived below them had been taken to hospital a few weeks ago and it was Sarah’s greatest fear that she wouldn’t come back. If that happened, there would be new tenants. The landlord had intimated several times that once the other tenant, an old family retainer, passed away, he planned to sell the property. Even though the place was damp and badly in need of decoration, Sarah had done her best to make it a nice home.

‘A bit of soap and water works wonders,’ she told her sister Vera when she’d first moved in, but she couldn’t help noticing her sister’s look of disdain. It was a far cry from the lovely house Sarah had shared with Henry, but without his wage, and because of a steep rise in the rent, it was impossible to carry on living there. Sarah and her girls had moved here three months after he’d gone, and up until today, everything had been going fairly well. To save money, Sarah had always made the children’s clothes and it had been her lucky day when she went to Mrs Angel’s haberdashery shop to get some buttons and bumped into Mr Lovett.

The shop was a jumble of just about everything. There were the usual buttons and embroidery silks, but Mrs Angel also stocked ladies’ underwear in the glass-topped chest of drawers under the counter and a few bolts of material. She would also allow her customers to buy their wool weekly and would put the balls away in a ‘lay-by’ until they were needed.

‘Madam, I have a proposition to make to you,’ Mr Lovett had said as he spotted Jenny’s little pink dress.

‘Mr Lovett has been admiring your handiwork,’ Mrs Angel explained. ‘I told him how popular your little kiddies’ clothes are.’

‘If you could make another little girl’s dress like that and a boy’s romper suit,’ Mr Lovett went on, ‘I think I could find a London buyer.’

‘It takes me a week to make one of those,’ Sarah had laughed. ‘The smocking takes ages.’

‘I can tell,’ he smiled. ‘And before you say anything, there will be no monetary risk to your good self. I shall supply all the materials.’

Sarah hesitated. Could she trust this man?

‘I’m sure Mrs Angel will vouch for me?’ he added as if he’d read her mind.

‘Mr Lovett is a travelling salesman,’ Mrs Angel explained. She was a matronly woman with a shock of white hair. Rumour had it that it had turned that colour overnight after her beloved husband was killed by lightning on Cissbury Ring.

Sarah had been slightly sceptical, but with Mrs Angel only too keen to provide the cottons and any other material she needed, the deal was struck. When she’d finished making the dress and romper suit, Mr Lovett was as good as his word. He’d been right. He’d had no trouble selling her handiwork to a shop in London where rich women were willing to pay the earth for things of such good quality. She knew he’d kept back some money for himself, and yet each time he’d taken an order he’d given her a whole guinea, more money than Sarah had had in a long time. He’d extracted a promise that if the customer liked her work, she’d be willing to do some more. Sarah didn’t need much persuading, even though, without a sewing machine, she’d had to sit up all hours to get them finished on time. She’d been so pleased with the money she’d saved, she’d decided to buy half a hundredweight of coal.

Outside, a lorry drew up and the driver switched off the engine. Lu-Lu wriggled to get down. Sarah let her go and looked out of the window. Oh no, Mr Millward was here already. She couldn’t take the coal without paying for it. How frustrating. Wood never gave out the heat that coal did, and after the horrors of the winter of 1947, she had thought that this coming winter was going to be one when they didn’t have to worry about keeping warm. Think, she told herself crossly. Where did you last have that purse?

There was a knock on the kitchen window and Peter Millward, his wet cap dripping onto to his face streaked with coal dust, smiled in. ‘Shall I put it in the coal shed then, luv?’ He was a kind man with smiley eyes, skinny as a beanpole, and at about thirty-four, was five years older than her. He had been married but his wife had died in an air raid, which was ironic because Peter, who had seen action in some of the worst places, had come through the war unscathed.

Sarah shook her head and rose to her feet. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, throwing wide the front door which opened onto the street. ‘I’m afraid you’ve had a wasted journey. I’ve changed my mind. I shan’t need any coal today.’

‘Shan’t need …’ he began with a puzzled expression. ‘But you only came to the yard and ordered this stuff an hour ago.’ He waited for an explanation and when one wasn’t forthcoming he said crossly, ‘I can’t be doing with being mucked about.’

‘I know,’ she said, ‘and I’m sorry.’

He stood for a second staring at her. Lu-Lu headed for the open door and Sarah bent to pick her up. The child was wet.

‘Was it Haskins?’ he blurted out. ‘Has he given you a better deal? Normal price is five bob a bag but I can knock another tanner off for the summer price.’

‘No, no,’ Sarah cried. ‘It’s not that. I won’t be needing it, that’s all.’

‘If you leave it until winter I may not be able to help you out,’ Mr Millward persisted. ‘And you won’t get it at the summer prices either.’

‘I know,’ said Sarah.

As she began to close the door, he said, ‘If it’s about the money, I can’t give you the whole five bags but I could let you have one if you and I could come to some sort of arrangement.’ He raised an eyebrow.

Sarah felt her face flush and taking a deep breath, she said haughtily, ‘I shall not be requiring your coal and I’d thank you to keep your special arrangements to yourself, thank you very much Mr Millward,’ before slamming the door in his face.

He was raising his hand as the door banged and he called out something through the wood, but Sarah turned the key in the lock and took Lu-Lu upstairs to her bedroom to change her nappy. As she washed her daughter’s bottom with a flannel, Sarah smiled at her child but inside she was raging. How dare he? What was it with men? Ever since Henry had gone, half the male population of Worthing seemed to think that she was either ‘up for a bit of fun’ or ‘gagging for it’ or available for ‘an arrangement’. Little did they know that after the way Henry had treated her, she didn’t care if she never saw another man again.

Putting the baby down, Sarah had another thought. Maybe Lu-Lu had taken her purse out of the basket while she and Mrs Rivers were having a cup of tea. She hadn’t stayed long because Mrs Rivers’ son, Nathan, had come home a bit earlier than usual, but there had been plenty of time for Lu-Lu to carry it off somewhere. As soon as Mr Millward’s lorry had gone, Sarah popped Lu-Lu into her playpen at the bottom of the stairs and knocked next door again.

‘Please don’t take this the wrong way,’ she began as she stood in Mrs Rivers’ doorway, ‘but did you find a purse after I’d gone?’

‘No, dear,’ said her neighbour. ‘Why, have you lost one?’

‘Yes,’ said Sarah. ‘I had it in the shops … obviously, but when I got back home and looked in my basket, it wasn’t there.’

The door was suddenly yanked open and Nat Rivers pushed past his mother. Sarah jumped. She didn’t like him. He was a big man with a generous beer belly, a mouth full of brown teeth and greying stubble on his chin. She’d never once seen him looking smart. Today he was wearing his usual grubby vest, no shirt and his trousers were held up with a large buckled belt. Nat Rivers had been in and out of prison all his life.

Mrs Rivers looked up at him anxiously and slunk back indoors.

‘Are you accusing my mother of pinching something?’ he snapped.

‘No, no of course not,’ said Sarah. ‘It’s just that …’

‘Then bugger off,’ he said as he slammed the door.

Sarah turned away despondently. She’d never be able to prove a thing of course, but she couldn’t help noticing that Mrs Rivers was looking rather flushed as she spoke – and her son’s attitude wasn’t exactly neighbourly. Almost as soon as the door closed, she could hear the sound of raised voices and what sounded like a slap. She hovered for a second, wondering if she should knock on the door again, but then she thought of the children. What good would it do if Nat came out into the street and hit her in front of them? It was a relief when everything went quiet.

Back home once more, Sarah had a heavy heart. It was so hard not to become bitter. She had thought that she and Henry were doing all right. He’d been looking forward to the birth of their second child. In fact, the whole time she’d been pregnant, he’d been like a big kid himself. He’d fussed over her and bought her flowers. He’d helped with looking after Jenny when her ankles swelled. Towards the end of the pregnancy, he’d taken Jenny out every Saturday so that Sarah could have a rest. When she and Henry were alone, he’d spent hours with his hand on her belly talking to his unborn child. He was so sure it would be a boy and she knew he was more than a little disappointed when Lu-Lu came, but she was such a beautiful baby right from the start.

‘You’re as good-looking as your daddy,’ she’d told Lu-Lu, knowing that Henry took pride in himself. He fancied that he looked like Ronald Colman with his light-coloured hair slicked down and his pencil-thin moustache. Sarah couldn’t see it herself but didn’t contradict him. Henry wouldn’t like that.

As Sarah told him time and again, it didn’t matter that they hadn’t got a son yet. The baby was healthy, that was the main thing, and eventually he seemed to accept that she was right. But then one day she came home from picking Jenny up from school to find that he wasn’t there. She’d reported him missing but the police seemed to think that because he’d taken a suitcase, there was nothing amiss, so she was left to soldier on by herself. She had hoped he would return, but it had been almost ten months now and she had to accept the fact that he wasn’t coming back.

Sarah was terrified that the welfare people would come and take the kids away, which was why it was imperative that she ask no one for money. She didn’t want anyone thinking she was an inadequate mother. She was determined to provide for them whatever happened. Over the months since he’d been gone, Sarah had pawned everything of value and only kept body and soul together by earning the odd shilling or two by cleaning the local pub in the morning and a couple of big houses during the day. It wasn’t easy because she had to take the baby with her and sometimes Lu-Lu was fractious because she had to sit in the pram all the time. Her sister had slipped her the odd five bob in the beginning, but she hadn’t offered anything lately and Sarah hadn’t asked. Mrs Angel had seen her skill with the needle and given her the occasional job mending a petticoat or making a baby dress, so when the children were in bed, she’d carried on working. In short, Sarah was willing to do anything which would raise a few extra funds provided it was honest, which was why meeting Mr Lovett had seemed like a godsend. All she could do now was hope and pray that he came back quickly with another order.

Despite how she felt about Henry, Sarah had kept the few personal things he had left behind. There was a brown suit, a little old-fashioned with turn-ups, a couple of jumpers she’d knitted him and a silver cigarette case. It was hallmarked and she’d often wondered why he hadn’t taken it with him. There was an inscription inside, Kaye from Henry. She had no idea who Kaye was and Henry had certainly never mentioned her. Sarah turned the case over in her hands. It was time to let it go. She could get good money for it and it would do far more good helping to feed her children than gathering dust at the back of the wardrobe. If he came back she would explain and hope that he would understand. She searched through the pockets of the suit and found a pair of baby’s booties. They looked brand new but she didn’t recognise them. The girls had never worn them and she could only surmise that Henry had bought them intending to give them to her but forgot. They would do for Jenny’s dolly. With determination in her heart, Sarah bagged everything else up ready to take it to the second-hand shop. She’d take the cigarette case to Warner’s antique shop by Worthing central crossing in the morning.

‘Vera,’ Sarah called out to her sister as they dropped their children off at school in the morning. ‘Could I have a quick word?’