Полная версия:

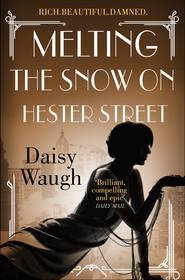

Melting the Snow on Hester Street

DAISY WAUGH

Melting the Snow on Hester Street

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Daisy Waugh 2012

Daisy Waugh asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007431748

Ebook Edition © March 2013 ISBN: 9780007487608

Version: 2014-12-17

Dedication

Darling Bashie,

movie star in the making (maybe)

This book is for you

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Max & Eleanor Beecham’s October Supper Party

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

The Nickelodeon on Hester Street

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Divorce Capital

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Floor Eight

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Sun on San Simeon Bay

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Read on for an extract from Daisy’s new book, Honeyville

Author’s Notes

Acknowledgments

Also by Daisy Waugh

About the Publisher

1

Santa Monica, 17 October 1929

‘What did he say, Charlie? Did he say it was gonna be just f-fine? Did he say it was OK?’

She was sitting at her dressing table, watching Charlie’s approach with anxious eyes, blue as the sapphires round her throat. But Charlie didn’t reply at once. He was thinking how graceful it was, the line of her neck: the nape, did they call it? He was sauntering towards her, across perhaps the most opulent bedroom in America. The sound of softly lapping waves filtered through the open windows and, beyond them, a long white beach gleamed in the early evening moonlight. Not bad, Charlie thought, as he often did. Not bad for a workhouse boy. And a chorus girl not so young as she pretended.

Beneath the sweet smells of her innumerable lotions, and the particular perfume, flown in from the fragrant hills of Tuscany, there was still a faint whiff of newness to the room: new fabrics and paints; new draperies and furniture … Marion’s beachside house (if you could call it a house) was only recently completed. One hundred and eighteen rooms in all, her lover had built for her. Thirty-five bedrooms, fifty-five bathrooms, a brace of swimming pools, a private movie theatre … everything, really, a woman’s heart could desire, so her lover believed. Wanted to believe.

And somehow Marion pulled it off: transformed this preposterous white elephant, into – not a home, exactly, but a place of merriment and warmth. A place where, despite the marble and the gold and the high ceilings and important stairways curling this direction and that, people could have a good time. They could feel relaxed. Charlie Chaplin felt very relaxed. At Marion Davies’s beachside palace. More relaxed, perhaps, than Marion’s long-time lover would have preferred.

But what can you do?

Charlie came to a stop just behind her, and then, absently, he dropped a warm kiss on that part of her – the nape? – which had been so distracting him, and breathed in the familiar perfume.

‘I didn’t ask,’ he replied at last.

‘You didn’t ask? Charlie! Why ever not?’

He kissed her again: inhaled the smell of her skin. ‘You really are … very lovely,’ he murmured.

‘Why didn’t you ask him, Charlie? I thought you were going to do that. Because I’m all ch-changed now, and ready to l-l-leave. You can see for yourself! I thought you were going to ask him!’

‘Well I didn’t ask, I informed. I told him that I would be bringing you along.’

‘No!’

‘In fact – now I think about it, I didn’t even do that … I informed whoever it was picked up the telephone. The maid, I guess—’

‘Oh God. Charlie!’

‘Sweetheart – it’s a small party. Max and Eleanor Beecham are splendid people … Smart people. You know them well enough. What do you think they’re going to say? The biggest movie star in history wants to come to their party, bringing with him the reigning Queen of Hollywood—’

‘It’s not funny …’

‘… The finest hostess, the most beautiful and talented actress—’

‘I’m not laughing, Charlie. Because you’re not being funny. Why’s everything got to be a joke with you?’

‘And a movie star, too – in her own right …’

‘Ha! If you don’t count it’s WR who pays for the movies.’

‘And – without wishing to put too fine a point on it – the beloved mistress of the most powerful man in the most powerful nation … in the world …’

‘Oh Charlie, no he’s not!’

‘Well, you may not think so.’

‘He’s the s-second. S-second most powerful. It’s what he says. After President Hoover. WR says …’

‘HA! He says that, does he?’

‘Because he’s more modest than you are, Mr Charlie Chaplin. So it’s no use your laughing. In any case, I don’t like it when you talk that way. It’s vulgar. It’s not attractive to me. And who says you’re the biggest star in America, anyway?’ She flashed him a provocative smile. ‘Your good friend Douglas Fairbanks certainly wouldn’t agree with you …’

‘Because my good friend Dougie is a fool …’

‘Mary Pickford wouldn’t agree.’

‘She’s a floozy.’

‘Jack Gilbert, John Barrymore, Gary Cooper, Thomas Mix …’

Charlie laughed aloud. ‘Sweetie, you insult me!’

‘… Rudolph Valentino …’

‘Ah! … But you’re vicious, Marion. Merciless. Cruel. Rudy may once have been more adored than I am, but in case you didn’t notice it, honey, Rudy is dead.’

She sighed. Bored of the game, now. ‘Well. I suppose I shall just have to change out of my fancy clothes then. Since you haven’t asked if I can come along. And you can go on your own. See how much I care …’

But Marion did care. More than she would ever let on to anyone: Not to her ageing lover, the newspaper magnate, multimillionaire, and possibly the second most powerful man in America, William Randolph Hearst. Nor even to Charlie Chaplin. Keeper of everyone’s secrets, including his own, and probably her best friend in the whole world. No.

She hated to moan, so she never did. But she was careful. There was never any knowing, even in this crazy town, who thought what about anybody else’s business. With Marion’s standing in Hollywood society being what it was – ever so high and yet ever so low and, frankly, internationally notorious – there was always a risk when she ventured out in public, and she preferred not to go where there might be a scene. As a result Marion rarely attended other people’s parties. And since her own were notoriously the wildest, most extravagant and most glamorous in the city, she didn’t generally feel she was losing out.

Even so, Max and Eleanor Beecham’s annual shindy had quite a reputation, and she’d never been to it yet. The couple had been holding the party at their house every 17 October since the building was completed, eight long years ago. The party was as close to a tradition as the Hollywood Movie Colony yet knew and, for that alone, it would have been treasured. Added to which, people said it was fun.

No one could compete with Marion when it came to scale: the Beechams were too smart to try. Their party was exquisite and select – never more than fifty people, but always the best (in a manner of speaking). Moguls and movie stars. Sometimes even a sprinkling of European royalty. One year, somehow, they’d managed to produce Mr and Mrs Albert Einstein.

Marion Davies imagined, correctly, that she would know just about every person present. Added to which, WR was out of town and she was tired of staying in. She felt like dressing up and getting canned in some decent company.

None of which would have been enough, ordinarily, to make such a difference. But last week a piece of information regarding the Beecham host and hostess had been brought to her attention and, before Marion acted on it, as she longed to do, she wanted to investigate further.

Most stars never touched their fan mail. But it was well known and often commented upon that Marion Davies read and replied to every one. This particular letter had been delivered, along with the usual weekly sackload, to her bungalow at the MGM studio lot. She was waiting to be called onto set, and it was lying at the top of a large pile of unopened letters on her assistant’s desk.

Dear Miss Davies [the letter began], I hope sincerely that you will forgive me for intruding in this way upon your precious time … I have long been a fan of all your movies, and I adored you in Tillie the Toiler …

It was a harmless beginning: crazy, perhaps – because everybody who wrote was crazy – but polite enough. She read on.

… However this is not why I am writing. I have a most unusual request …

After she had finished reading it, Marion wondered if it was luck or something more sinister which had persuaded the writer to approach her for help. For sure, she and Eleanor had been photographed together at a handful of Hollywood gatherings: they were indeed friends, at least up to a point. And they were of similar ages, perhaps a little older than most of the leading ladies. But since they both lied about that, it was hardly relevant.

There were the rumours about Marion, too, of course, which would have made her an appealing target. But the fans shouldn’t have known about them: not even a whisper. The fans shouldn’t have known anything – not about her, nor about Eleanor – except what their studio publicists put out.

Of course it was possible – likely, even – that similar letters were languishing, unread or disbelieved, on the desks of film stars’ assistants all over town. In any case, it so happened that on this occasion, such a letter could not have been better directed.

When Marion read it, it touched a raw nerve: broke open a secret sore. She did something she only ever did alone, and then only rarely: she wept. Not for herself, but for the Beechams. Later, when they came to fetch her onto set, she locked the letter inside a small jewel box and said not a word about it to anyone.

‘What do we know about M-Max and Eleanor Beecham, Charlie?’ Marion asked him suddenly. ‘I mean to say, just for example, do you imagine it’s their real name?

‘Beecham?’ Charlie laughed. ‘It would make them quite a rarity in this town if it were. Why don’t you ask them tonight?’

‘I might j-just do that …’

Charlie let it hang there. She would do no such thing, of course. Say what you like about Marion – and people did – but she was never intentionally impolite or unkind.

Even so, Charlie noted, she was on edge this evening. Something was bothering her. ‘What’s the trouble?’

‘Nothing’s the trouble, Charlie. We can be curious about each other every once in a while. That’s all …’ She stopped. ‘Only, don’t you wonder sometimes, what draws us all to … w-wash up w-where we do? The way we do? The Beechams, for an example. There they are, y’know? Part of the scenery since I don’t even know how long. Can you remember? When you f-first laid eyes on the Beechams? They’ve just been there. Beautiful and clever and on top of the world … But where did they come from?’

‘He was at Keystone when I first came to Hollywood. Playing piano on set … They all adored him there.’

‘Well, I know that.’

‘Then they teamed up with Butch Menken, didn’t they? … They made some very fine movies. Between them. You can’t say they’re not talented.’

‘Of c-course I’m not saying it, Charlie. Max Beecham is terrific. One of the best in the wide world … Everybody knows that.’

‘Let’s not go too far.’

‘Well I think he is. I think he’s a great director, and even if it wasn’t such a hit as some of his other ones, I think Beautiful Day was the best – the best t-talkie – of last year. Including mine – and you didn’t bring any out, Charlie, and I specially said t-talkie – so I can say that. C-can’t I?’

‘Of course you can, sweetheart.’

‘… I also think Eleanor is a g-great actress.’

‘No better than you are, Marion.’

‘But where did they come from? Who in hell are they? They seem so … together. They’ve got that beautiful, perfect house, and everybody knows they just adore each other – they’re probably the happiest couple in Hollywood …’

‘It’s not saying so much.’

‘But you can see the way they look at each other.’

‘They seem …’ Charlie thought about it. ‘They do seem to care for each other. Yes.’

‘And I mean to say they’re a mystery. Don’t you think?’ She stopped. ‘I just wonder …’

‘Wonder about them especially? Or about everyone?’

‘What’s that?’

‘You could ask the same questions about any of us. We all have secrets.’

‘Huh? I thought you and I were pretty close friends.’

‘Of course we are. But we don’t know everything about each other.’

‘I should certainly hope not!’

‘Exactly. We all embellish. It would be dull if we didn’t. Look at Von Stroheim! One of our greatest directors, yes. But do you suppose he’s really a count, as he pretends to be?’

‘Oh, forget it,’ Marion said, suddenly sullen. ‘It doesn’t even m-matter, anyway.’

‘Why ever not?’

‘I shouldn’t have b-brought it up. Eleanor Beecham’s a terrific lady. That’s all I’m saying … Let’s get going, shall we? Are you taking me to this stupid party or aren’t you?

Charlie checked his not-bad-for-a-workhouse wristwatch. Heavy gold, it was. Cartier. A gift from Marion. ‘We’re too early yet,’ he replied. ‘In any case, Marion, the mood you’re in, I’m not taking you anywhere. You’re so damn miserable you’d reduce the entire party to blubbering tears in less than a minute.’

‘Ha! I would not!’

‘Nobody’d want to talk to you.’

‘Very funny.’

‘Except for me of course … I always want to talk to you.’

‘Well, that’s not true— Oh!’ she interrupted herself. ‘But you know what we need, Ch-Charlie?’ she cried, brightening all at once. ‘Cocktails! Don’t you think so, h-honey? Then we’ll definitely be in the mood for a party!’

2

High up in the Hollywood Hills, at home in their splendid Castillo del Mimosa, Max and Eleanor Beecham were nicely ahead of schedule. Between them, as always, they had everything for the evening under good control. Max had paid sweeteners to all the necessary people to ensure the hooch flowed freely all night. Cases of champagne, vodka, Scotch and gin, and the correct ingredients for every cocktail known to Hollywood man had been delivered discreetly in the early hours of the morning, and tonight the place was heaving with the finest liquor money could buy. Al Capone himself would have been pushed to provide better.

Meanwhile Eleanor had seen to it that the halls, the pool and garden were decked in sweet-smelling and nautically themed California lilacs: white and blue – a subtle reminder to everyone of Max’s nautically themed latest movie, Lost At Sea. There was a jazz band running through its numbers in the furthest drawing room, where carpets had been removed and furniture carted away; and in front of the house, on the Italianate terrace, beneath a canopy of blue and white nautically themed silk flags, there stood a long banqueting table. It was swathed in silver threaded linen, with a plait of bluebells curling between silver candelabras. The table shimmered under the marching candles and the artful electric light-work of Max’s chief gaffer – the most sought-after lighting technician in the business – fresh from the set of Lost At Sea.

Eleanor was longing for a drink. But she was of an age now – somewhere in her mid- to late thirties – where even the one drink made her face wilt just a bit, and like any professional actress she knew it well. She also understood how much it mattered. So she was holding out on the liquor until all the guests had arrived and they could move onto the artfully lit terrace.

She was holding out changing into her evening dress, too, for fear of creasing the damn thing. In the meantime – though her short dark hair, shorn into an Eton crop, was perfectly coiffed, and her finely arched eyebrows, her full, wide mouth, her green eyes were perfectly painted – she was still wrapped in an old silk bathrobe.

She had already busied herself with a final, unnecessary tour of the house: just to be extra certain that everything was in place. And so it was. A fleet of waiting staff had already reported for duty and were in the hall, receiving final instructions from the Beecham housekeeper.

And so she stood: at a loose end on her Italianate terrace, gazing at those silken flags, fluttering like bunting in the electric light. They’d been Max’s idea – because of the movie. Had he seen them yet? She supposed not. Eleanor hadn’t realized, when the designers described them to her, quite how low they would hang, nor quite how they would resemble … Gosh, she hated them. But it was too late. It was just too bad. Max had said he wanted them. She wondered if he’d had any idea …

Eleanor had nothing much to do. The last few lobsters were being boiled in their shells in the kitchen: she could hear the squeak. The scream. She could hear the scream and it made her shiver. The cook had prepared the hollandaise – the oysters were set in aspic. It was done. Everything was done. She sighed. Nervous as hell: of course. Nervous as ever – but this time, somehow, she was nervous without being excited. When had this wonderful party – this highlight of the Hollywood social calendar, this manifestation of her and Max’s extraordinary success – when had it lost its magic and turned into a chore?

She wondered briefly, bitterly, was it a chore to Max too? Who the hell knew?

She’d left him upstairs, changing, but she needed to discuss with him various things. She needed to tell him about the problem with the ice sculptures in the front hallway. And she needed to say something about the far arc light, behind the mimosa on the eastern end of the terrace. It looked as if it might be dipping slightly … She wandered up to join him.

He was already bathed and dressed: bending awkwardly over the looking glass at her dressing table, slicking back his dark hair with one hand, smoking a cigarette with the other. He was wearing a white evening jacket and matching, loose-fitting pants. Handsome as ever. It always struck her, even now, in spite of everything, just how handsome he was: fit, slim, well built, dark, elegant – good enough to be a movie star himself, if he’d wanted it. She still loved the look of him. Sometimes. And it still took her by surprise.

‘Hello, handsome,’ she said, putting her two arms around his waist – sensing his body tense at the intrusion, and hating him for it – hating herself for not having remembered, once again, how painful it was, to try to breathe warmth on his coldness. ‘Nice jacket! I’ve not seen that get-up before – have I?’

He glanced at her reflection as she stood behind him; at the green eyes, not really smiling at him. He turned and pecked her on the end of her nose. ‘You’ve seen it often,’ he said smoothly, removing her hands. ‘By the way,’ he added, ‘did Teresa tell you? Chaplin called.’

‘He did?’ She sighed, exasperated. ‘When? This evening? Because if he’s not coming, he might have told us so before this evening.’

‘Sure he’s coming! He called to say he was bringing Marion.’

‘Oh! … You mean Marion Davies?’

‘Of course, Marion Davies. What other Marion?’

‘Well … that’s a bit awkward …’

‘I don’t see why. Marion’s all right.’

‘I didn’t say she wasn’t.’ Eleanor turned away from her husband, sat herself on the edge of the marital bed: a bed so wide they could have fitted a lover in there each, and hardly bumped elbows. She sighed again. Who in hell could she put beside Marion for dinner?

‘I thought it was kind of flattering,’ he said, smiling a little, elegantly shamefaced. ‘Maybe now she’s gatecrashing our party, she and Mr Hearst will finally invite us up to San Simeon.’

‘Hah …’ Eleanor offered up a soft, half-laugh. ‘Yes indeed … Wouldn’t that be something?’

The beauty of San Simeon was legend. The luxury of Randolph Hearst’s fairytale castle 200 miles north of Los Angeles, perched high on a fairytale hill overlooking San Simeon bay was legend, too. But the house parties he and Marion held there were the greatest part of the legend of all – not just in Hollywood but around the world. Invitations were delivered by chauffeur, in envelopes so fine, so deliciously soft and fragrant they might been pulled from Marion Davies’s own underclothing drawer. Nobody turned them down.