скачать книгу бесплатно

As soon as my house was male hormone-free I made a quick call to both my kids. Both adult now and with their own families (Kieron had not long had his first baby) it was odds on that either or both would pop round at some point. We had a bit of an open-door policy in that way, and what mum doesn’t like seeing her grown-up kids?

Today, however, it made sense to ask them not to call round, so that I could give Connor a chance to settle in. And if that went okay, we could all get together on the Sunday. In my experience, something like a big family picnic was one of the best ways to take a troubled child out of themselves – fresh air and exercise being two of the best medicines around.

That done, it was time to go and power up my laptop so I could see what might have fetched up in my inbox. And something had. And it made interesting reading.

It seemed Connor had been born in south London. In his early years he’d lived there with his mum – who was called Diane – and his dad, Connor senior, together with an older brother and sister. These older siblings were, according to the notes, Connor’s polar opposites, in that, while they were model kids (if such a thing exists) he’d been labelled a ‘problem child’ early on; screaming all day for no apparent reason, and violent from the moment he could walk. He had been excluded permanently from every school he had attended in his short life (including nursery, where he was already deemed too aggressive to be around other kids), and by the time he was seven he’d already been tagged ‘streetwise’.

I continued to read with a sense of depressing inevitability. Though it seemed no one had commented on or suggested reasons for Connor being such an apparently difficult toddler, one thing leapt out as a factor that might exacerbate the problem; that his father had been in and out of prison all his life. Connor senior was quite the criminal, it seemed; something not usually conducive to family life, and when Connor was five his wife left and then divorced him.

Then came the nugget that I couldn’t help but home in on. That she’d left him, taking only two of her three children. She simply left for some village in the north-east, close to Scotland, and as it coincided with a period when Connor senior was at liberty, she left little Connor behind with his dad.

I couldn’t help but sigh. I could never do such a thing. I struggled to understand how a mum could leave her kids at the best of times – in all but the most extreme of cases – but to take two and leave one with a jailbird husband? How much more completely could a child be rejected? I read on. It seemed Dad had been happy enough to keep him, but within six months he’d received yet another prison sentence and at that point five-year-old Connor had been taken into care. He’d been part of the system ever since.

It was dreadful reading – starts in life don’t come much worse – and I felt genuinely moved, not to mention slightly sickened, thinking of where he’d come from and just how damaged he must be as a consequence. I wasn’t alone; various social workers and carers had made similar observations, one noting only recently that, at the age of just eight, Connor truly believed himself to be ‘properly grown-up’, had seen enough of life to know ‘exactly what was what’ and that half the adults he’d encountered ‘didn’t have a clue’.

I closed my laptop. Bye bye weekend. This clearly wasn’t going to be an easy one. Though I already knew that – mine was a job that required me to know that – I also knew instinctively that I now had to make a choice. Not about hanging on to Connor – our next long-term placement would be decided in consultation with John Fulshaw – but about how I – or, rather, we – approached the next two days.

I had two choices. I could fill the time with fun things to do, keep Connor happy and act like he was just with us for a little holiday, or I could choose to try to help in some way. That would mean touching on some very painful areas for Connor and ‘interfering’ in his life, and I knew doing that was tantamount to creating all kinds of trouble. But to opt for simple containment would leave me feeling that I wasn’t doing my job. And that, admittedly to my own detriment at times, simply wasn’t in my nature.

John Fulshaw was still away, of course, but I could hear him like Jiminy Cricket on my shoulder. He’d have looked at the notes and advised against this particular bit of respite, for sure. I could actually hear him telling me not to take it on, saying that since we’d decided to take on Tyler permanently we needed to take a break before embarking on our next quest. Yes, do a bit of respite, perhaps – for quiet, biddable children who happened to find themselves in unfortunate circumstances – but save our emotional energy for our next long-term challenge; not take on a kid with a dossier of escapades that made for more eye-popping reading than James Bond’s.

John would probably have been right, but I’d committed to it now, so it was up to me to advise me, and I told myself sternly that I should play things by ear. Much as my instinct was to cast myself as a mixture of superhero and avenging angel, the best thing to do would be to see how things went. In any case, half the day would be gone before Connor even got to us; I’d never been to Swindon but I knew it was at least a couple of hours’ drive away, probably more. And he’d be tired, he’d be shaken, he’d be scared; hopefully he’d be contrite. Which thoughts showed just how much I didn’t know.

Mike and Tyler arrived back from football at one o’clock, exactly the time I expected to receive Connor, so I hustled them in, ordered them both to the bathroom with a command of ‘Get those filthy sweaty things off!’ and flew around with a can of air freshener. Only then, with my home feeling fit to receive visitors, did I take up a vigil by the living-room window.

‘Is that a security van?’ Tyler wanted to know, once he and Mike had come to join me.

‘Certainly looks like one,’ Mike agreed. He laughed. ‘Though I’m sure it’s not. It’s probably just –’

‘It bloody is,’ I said, gawping at what had just pulled up outside our house. ‘Look at the writing on it! And it’s got those armoured windows and everything.’

‘It is,’ Tyler agreed. ‘It’s one of those vehicles they use to transport criminals back and forth from where their trials are. I remember seeing them when we were there. Don’t you remember?’

Indeed I did, one of our first outings with Tyler having been to accompany him to court.

‘Bloody hell, Case,’ Mike observed before I could answer. ‘What the hell did he do?’

We all watched, agog, as the driver got out. He was a huge man – as tall as Mike and a great deal wider – and when he went round the back to open it he was joined by another man-mountain; they were clearly hand-picked for the job.

Which was what made what happened next seem even more incongruous. Because what emerged from the van was a slip of a boy; if I’d been asked his age, at this distance I would have guessed somewhere around six. They were joined by a third man – three men! Come all this way with him! And all three, amazingly, escorted the lad up our path.

I realised we all had our mouths hanging open. ‘Come on,’ I hissed. ‘Come away from the window. The kid’s probably petrified!’

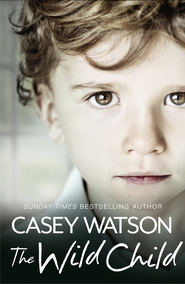

Not, it had to be said, that he looked it. It was hard to drag ourselves away from watching this tiny thing, his head a mass of blond, cherubic curls, who was currently marching towards our front door. Really marching, too. Like you see young boys doing when they’re playing soldiers. Arms stiff and swinging in time with their feet, expression blank, head held high. I had never seen anything like it in my life and half expected one of the ‘guards’ to shout ‘Halt!’

I rushed to open the door, closely followed by a bemused Mike and Tyler. Trying to ignore the hard, inscrutable gazes of the three men, I immediately bent down so I could smile at Connor at his level. ‘Hiya, sweetie,’ I said, touching his shoulder as I spoke. ‘I’m Casey, this is Mike and this is Tyler.’

I then stood upright to speak to the men, who returned my chirpy greeting almost as if they were robots. I wasn’t sure they were much used to delivering small children to middle-aged women in the suburbs. ‘Do you have his things?’ I followed up. ‘His clothes and the usual paperwork? And how about a cup of tea or something?’ I added. ‘You’ve had a long drive. Come on, please do all come in.’

I moved to one side, then, to allow the procession to pass but the men stayed where they were. The one at the back passed the small suitcase he carried to Mike and then a large envelope to me. ‘We won’t come in if you don’t mind,’ the front man replied. ‘We’ve got a long drive back and want to crack on.’ He then turned to Connor and cracked a smile, too, finally. ‘You’ll be alright here, son,’ he said, patting him on the head, closely followed by the second man. ‘And don’t forget, you just be good for these people, won’t you?’

Connor nodded solemnly. The two seemed to have bonded en route. He then turned and smiled shyly up at me.

‘I am a good kid you know. I dunno what all the fuss is about really. But like I told these fellers on the way, it’s ’cos me dad’s a famous gangster from London. They all give me grief about it, but it’s alright, I can take it. There’s not much fazes me. You got anything to eat? I’m starving!’

I grinned back, delighted by the warmth in his smile and the endearing ‘Artful Dodger’ way he spoke. I was also aware of Mike and Tyler trying not to laugh. ‘Go on in, then,’ I said. ‘Mike and Tyler will show you your room while I sort you out some food. Cheese sandwich and some crisps? How about that?’

‘Sounds safe,’ he said, hopping over the step and coming in.

I thanked the men for bringing him and, as soon as Connor was out of earshot, I asked the question that had been on my mind since they arrived. ‘This all seems very odd,’ I said. ‘Do children in care always get transported like this from your neck of the woods?’

The man at the front laughed. ‘Nope!’ he said. Then his face was once again serious. ‘But then again, not all children are like young Connor. Don’t let them big blue eyes fool you, Mrs Watson. He’s already bitten a chunk out of one of my men, and only ten minutes ago said his dad would slit my throat the minute he gets released.’

He patted my shoulder, just as he’d done to Connor’s head. ‘Stay safe,’ he said cheerily as he led the procession back to the van.

Chapter 4 (#u9fd89db2-22dc-5e4c-a4f5-6969c5892181)

I stood and watched the huge vehicle turn around and drive away, letting the shocking things he’d said to me sink in. They had just seemed so at odds with the way Connor looked and had behaved – well, so far – that my instincts were all over the place; I really didn’t know what to think.

I’d yet to hear from the care-home manager, so I still felt somewhat ill-informed; I’d have liked to know the circumstances around the incident that had brought him here, but right now all I had to go on were the email I’d already studied and the envelope I had in my hand. I ripped it open and had a flick through while Mike and the boys were still out of the way, but there wasn’t much more than I’d been told earlier. Well, apart from some further info on how he’d got hold of an iron bar. It seemed he’d acquired it from the grounds of the home, where some repairs were being done to some of the outbuildings. Apparently left behind by a workman, it had found its way into Connor’s hands a few days earlier – he’d admitted to having it hidden under his bed.

‘For protection’ had been his answer when he’d been asked why he’d taken it, but it had certainly not been used in defence. No, it seemed the social worker – a Mr Gordon – had wound him up in the dining room, so he’d gone to his room, retrieved the bar, which was apparently some part of an old window, and then duly caused mayhem over breakfast.

This morning’s breakfast. All that trouble caused, and on this very morning, by the little dot of a kid upstairs. Hearing the stairs creak, I stuffed the papers back into the envelope.

It was Mike. ‘Told them I’d call them when there’s some food ready. Ty’s helping him settle in. Anything juicy in there?’ he added, nodding towards the paperwork. I paused, wondering whether to try and sugar it. I decided not.

‘He does appear to be a bit worse than we first thought,’ I said, keeping an eye on the door. ‘It certainly doesn’t make nice reading. I think we’re going to have to keep a close eye on him.’

He held his hand out for the envelope. ‘Let’s have a nose, then. Don’t worry. He’s busy unpacking and Ty’s promised him they can play on his Xbox.’

I handed it over. ‘Well, I guess all we can do is treat him as we find him and play it by ear. Julie did say these outbursts invariably follow a pattern. That once he’s messed up his placements he goes through a period of remorse. Let’s hope he’s in reflective mood today, eh?’

‘Placements plural?’ Mike said. ‘How many has he been through?’

‘More than are commensurate with peace, love and harmony,’ I told him. ‘So let’s make sure he sees some while he’s with us. I’ll leave them for a bit, then how about we take them both out? Maybe even stay out for tea. We’ll just keep him busy,’ I added, as Mike finished scanning the notes.

‘Hmm,’ he said. ‘Be the other way around, I reckon.’

He wasn’t wrong. After he went into the lounge to watch his Saturday sports programme I quickly made both boys a sandwich, then took them up; if they were settled with the Xbox, I was happy enough. They could get on and get to know each other over some mutual game they liked while I dealt with the laundry, and we could head off on our outing a little later.

I reached the top of the stairs and smiled as I heard boyish laughter coming from Tyler’s room. Tyler was routinely great around younger kids, not just because he had his own little brother (whom he still saw pretty regularly, even though he had no contact with his dad or stepmother) but because he spent so much time around my own grandchildren.

I hovered a moment, listening – you could glean lots by listening to what kids chatted about when out of earshot – and, as a result, my smile didn’t stay in place long.

‘Mate, you’re almost a man at your age,’ Connor was saying. ‘Don’t tell me you never look at tits.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: