Полная версия:

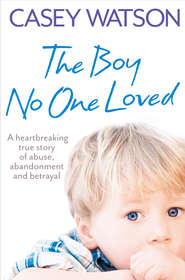

The Boy No One Loved: A Heartbreaking True Story of Abuse, Abandonment and Betrayal

Casey Watson

The Boy No One Loved

Copyright

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published by HarperElement 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

THE BOY NO ONE LOVED. © Casey Watson 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Casey Watson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9780007436569

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2011 ISBN: 9780007436576

Version 2016-10-18

Dedication

To my wonderful and supportive family

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Funny the little details that tend to stick in your…

Chapter 2

I followed Kieron up the stairs, Riley close behind me,…

Chapter 3

I’m mad about Christmas – always have been and always will…

Chapter 4

I woke on Christmas morning in my usual good spirits,…

Chapter 5

One of the main things Mike and I had to…

Chapter 6

‘I just can’t help it,’ Justin said. ‘I know I…

Chapter 7

We’d been sitting there together for an hour by now.

Chapter 8

It was the following Saturday morning and I was on…

Chapter 9

It was a freezing cold day at the end of…

Chapter 10

The end of the week saw another email arrive from…

Chapter 11

April had arrived and with it some slightly warmer weather…

Chapter 12

Sunshine, I thought happily, as I yanked open the bedroom…

Chapter 13

‘Aw, Mum. Pleeeeaaase!!!’

Chapter 14

‘Mrs Watson? It’s Richard Firth, Head of Year Seven at…

Chapter 15

After the whole issue of the exclusion and Justin’s further…

Chapter 16

I woke up the next morning with a really thick…

Chapter 17

It was late August and, now that Justin was making…

Chapter 18

‘Spaghetti bolognaise!’ Justin announced with an excited flourish. ‘I’m gonna…

Chapter 19

Though we didn’t know for sure (and, as it turned…

Chapter 20

It was now late September and I was beginning to…

Chapter 21

‘Aw, it’s not fair. I soooo want to come!’ Riley…

Chapter 22

It was a Friday morning, just a week after Justin’s…

Chapter 23

‘What shall it be then, Casey, do you think? Shall…

Chapter 24

Deep breath, I said to myself slowly. Deep breath. It…

Epilogue

Exclusive sample chapter

Casey Watson

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Prologue

His little brothers, the boy saw, were both covered in shit. They’d removed their full nappies and smeared each other in it, while their mother’s dog – a spiteful brown terrier – was busy licking what remained from the bars of their shared cot.

He shooed the dog away and, gagging now, lifted both boys out, and then went to fetch a quilt from his mother’s bedroom. Where had she gone this time? Why was she never there?

He took the boys downstairs, used the quilt to wrap them up warmly on the couch, and tuned the TV to a channel that was showing cartoons. ‘We’re hungry,’ the older one kept repeating plaintively. ‘We’re hungry, Justin. Please Justin. Find us some food.’

There was nothing. There never was. Though he looked for some anyway. In all the cupboards. In the drawers. In the big dirty fridge. He felt tears spring in his eyes. And he also felt anger. He looked at his little brothers, at their hopeful, expectant faces. What was he supposed to feed them with? What was he supposed to do?

Then, suddenly, in that instant of despair, there came clarity. He didn’t have to think. He knew exactly what to do. As if on autopilot now, he took his brothers out into the front garden, sat them down on the grass – still wrapped in the grubby quilt – and told them to stay where they were.

He then returned to the house and looked around the living room for the lighter. Picking it up, he calmly flicked it at the couch. He continued to do this till the couch began burning and then he went and set fire to the curtains.

The dog came downstairs then, its face all smeared with the contents of the brothers’ nappies. The boy ran to the kitchen, to the cupboard under the sink, where there was a container of fluid which he knew was for the lighter. Grabbing this, he returned to the living room again, and squirted the fuel all over the animal’s filthy face.

Taking one last look around, he walked out of the front door, closing it carefully behind him. He then joined his brothers under the quilt, on the grass, and calmly watched while both home and dog perished.

His mother was located, by the police, three hours later. She’d apparently spent the day at a friend’s house. The little boy was just five and a half years old.

Chapter 1

Funny the little details that tend to stick in your mind, isn’t it? The day Justin, the first foster child to ever be placed with us, was due to arrive – a bright but chilly day on the last Saturday before Christmas – all I kept going back to were the same old two things. One of them was just how desperate the social worker seemed to be that we should agree to have him, and the other was the fact that I had black hair.

And it wasn’t just me either. My daughter Riley, now 21 and so supportive of the whole project from day one, had the same head of black hair that I did. We’d both of us inherited our raven locks from my mother and one thing I knew – and I really knew so little about Justin – was that he had a very powerful aversion to women with black hair.

I straightened his England football-team-themed duvet cover for the umpteenth time that morning, and tried to put the negative thoughts right out of my mind. I was trained to do this job, I told myself. So was my husband, Mike. Plus I already had several years of experience looking after difficult children. And this was the new career I’d chosen for myself, wasn’t it?

But along with the anxiety, I also felt proud. I looked around me and found myself smiling with satisfaction at what I saw. I certainly couldn’t have thought harder about the way to do his new bedroom. Because one of the few things we did know was that Justin liked football, we quickly settled on that as a theme. So we’d done out the spare room in black and white and splashed out on some special wallpaper that made one of the walls look like it was a crowd at a stadium. We’d laid a green carpet, for a pitch, added a football-themed frieze, and I’d trawled charity shops endlessly for the books, games and jigsaws that I knew my own kids had enjoyed at his age. We also knew he liked movies, especially Disney films, apparently, so we’d bought him a starter pack of those too. I had agonised over every detail, every decision, every tiny item, because it meant so much to me to do everything I could to help him feel at home. The one thing I didn’t know was what team he supported, so, till I did know, I’d pinched my son Kieron’s old duvet cover for him. I reasoned that England was a pretty safe bet for any football-mad eleven-year-old boy.

I checked the time on the big blue clock Mike had fixed on the wall. Almost eleven. They would be here any minute, I realised. And, as if by magic, I heard Mike call my name from downstairs.

‘They’re coming up the path, love,’ he said.

I had met Justin already, of course, just the previous Tuesday. In fact, it had only been a week since we’d been asked to consider our first placement at that point, and only eight days since I’d left my old job at the local comprehensive school. It had been an intense week, too, with everything seeming to move so quickly, and even though the way all these things were done was still new to us, Mike and I had both felt there was a real sense of desperation in the air. John Fulshaw, our link worker from the fostering agency we worked for, had been clear: this was not something we should undertake lightly. How little did we understand then just how true his words would be.

We’d been assigned John as our link worker when we’d first applied to be foster carers and we’d struck up a good relationship with him right away. By now we also felt we knew him quite well, so if John was anxious it naturally made me anxious too. Not that we weren’t anticipating challenges. What Mike and I had signed up for wasn’t mainstream fostering. It was an intense kind of fostering, intended to be short term in nature, which involved a new and complex programme of behaviour management. It had been trialled and was proving very successful in America, and had recently started to be funded by a number of councils in the UK. It was geared to the sort of kids who were considered unfosterable – the ones who had already been through the system and for whom the only other realistic future option was moving permanently into residential care. And not just ordinary residential care either – they’d usually already tried that – but, tragically, in secure units, many of these kids having already offended.

‘The problem,’ John had told me, during our first chat about Justin, ‘is that we know so little about him and his past. And what we do know doesn’t make for great reading, either. He’s been in the care system since he was five and has already been through twenty failed placements. He’s been through a number of foster families and children’s homes, and now it’s pretty much last chance saloon time. So what I’d like to do is to come round and discuss him with you both personally. Tomorrow, if it’s not too short notice.’

As a family, we’d talked about that phone call all evening, trying to read anything and everything into John’s few scraps of information about the child he wanted us to take on. What could the boy have done to end up having had twenty failed placements in just six short years? It seemed unfathomable. Just how damaged and unfosterable could he be? But since we knew almost nothing, it was pointless to speculate. We’d know all that soon enough, wouldn’t we?

Not that, come morning, there was much more to know. John had arrived and, as soon as I’d made us all coffee, he got straight down to the business of telling us.

‘It was a neighbour who alerted social services initially,’ he explained. ‘He’d been to their house several times, it seems, begging for food.’

We remained silent, while John sat and read from his notes. ‘Family Support followed it up, by all accounts, but it seems the mother managed to convince them that she was coping okay – that she had just been through a bad patch at the time. Justin himself, it seems, corroborated this – certainly managing to convince them that the right course of action was to let things ride for a while. And then two months later, emergency services were called out to the family home by a neighbour. Seemed he’d been playing with some matches and burned the house down. Apparently the mother had left him and his two younger brothers –’

‘Younger brothers? How old were they?’ I asked him.

John checked his notes again. ‘Let me see … two and three when it happened. And they’d all apparently been left alone in the house while she went off to visit a boyfriend. Seems the family dog died in the fire as well.’

Mike and I exchanged glances, but neither of us spoke. We could both see there was more for him to tell us.

John glanced at us both, then continued. ‘It was after that that the mother agreed to have him taken into care. Under a voluntary care order – seems no fight was put up there about holding on to him; she was happy to let him go and accept a support package for the younger two – and he was placed in a children’s home in Scotland, with contact twice monthly agreed. But it broke down after a year. It seems the people at the home felt they could do nothing for him. He was apparently’ – he lowered his eyes to check on the exact wording – ‘deemed angry, aggressive, something of a bully, and unable to make and keep friends. They felt he needed to be placed in a family situation for him to make any sort of progress.’

He leaned back in his chair then, while we took things in. The language used could have been describing an older child, certainly – an angry teenager, most definitely – but a five-year-old child? That seemed shocking to me. He was still just a baby.

‘But he didn’t,’ I said finally.

John shook his head. ‘No, sadly, he didn’t. Because of his behaviour, he’s been nowhere for more than a few months – no more than a few weeks, in some cases – since then. He’s physically attacked several of his previous carers and has simply worn the rest of them out. So there we are,’ he said, closing his file and straightening the papers within it. ‘Twenty placements and we’re all out of options.’ He looked at both of us in turn now. ‘So. What do you think?’

And now here I was, just a few days before Christmas, and this child, this ‘unfosterable’ eleven-year-old child who’d burned down his home at the tender age of just five, was about to become our responsibility.

I walked down the stairs just as I could see a shadow approaching in the glass of the front door. I noticed how smoothly my hand slid down the banister, and smiled. I’d been cleaning and polishing like a mad woman all morning, flicking my duster manically here, there and everywhere, and moving all sorts of stuff around the place. Mike, bless him, had been getting on my nerves since we’d got up, assuming, with his man-wisdom, that since I was obviously so stressed, that he’d be doing me a favour by anticipating my every next move, and being one step behind me at all times.

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ I’d snapped at him, not half an hour earlier. ‘How can I get anything done in this place with you on my tail all the time?’

He’d shot off then, probably grateful to get out from under my feet. But he’d been right. I was so nervous that I actually felt physically sick. I’d never been so nervous about a new job, ever. Probably because this was going to be like no other new job. Because it wasn’t just a job, it was a whole lifestyle. This was not nine till five, this was twenty-four-seven. Gone would be our cosy evenings in, cuddled on the sofa, just me and Mike together, and gone would be the lazy weekends we’d begun to start enjoying since Riley had moved out and Kieron had turned nineteen. There was no turning back, though. I’d said yes. I was committed. He’s only eleven, I kept telling myself sternly. He’s been through some bad times. It was just the lack of knowing what that was so worrying.

I reached the bottom of the staircase just as Mike reached the door. I took a deep breath. This was it, then.

‘Hi Justin!’ I said brightly as the door opened to reveal him, accompanied by Harrison Green, Justin’s social worker, who’d brought him along for our initial meeting the previous Tuesday. I hadn’t been sure about Harrison when I first met him; he seemed a scruffy sort of character to be a social worker, to my mind. In his mid-fifties, he had a mop of unruly, greying hair that looked like it hadn’t seen a comb in a long while, and a generally unkempt air about him. But perhaps that was what long-term social work could do to you. I’d got little sense of what Justin himself was like on that occasion, other than that he was surly, a little awkward around us and a little lacking in all the normal social graces. Offered a biscuit, for example, and he’d immediately pounced on the plate, taking as many in one hand as he could get his fingers round, and immediately stashing half in his trouser pockets. But his lack of etiquette was hardly surprising given his situation, was it? So I wasn’t concerned about such small, trifling details. Not at all. Those sorts of things could all be learned. It was the deeper stuff, the psychological damage, that most concerned me. Could the manifestations of that damage be unlearned? That was what was key.

One thing that had happened was that we’d been given more background to chew over. While Mike had been showing Justin around our home that day, Harrison had taken the opportunity to fill me in on more of the details of his own.

‘The truth is that he’s attacked a number of his carers,’ he’d told me gravely. ‘With both fists and with kitchen knives, apparently.’ He’d paused then. ‘He’s also threatened to take his life on a number of occasions, and did once actually try to hang himself. From some goalposts on the school playing fields.’

I’d listened in shock, mentally storing everything up so I could recount it all back to Mike later. It was then, too, that Harrison had passed on the news that Justin seemed to have a particular aversion to women with black hair. But he’d also been positive about the potential for his future progress. Justin’s current situation had been as much to do with the carers as him, it seemed. According to Harrison, at any rate, they were too inexperienced to deal with Justin’s refusal to accept boundaries. And boundaries were what he needed more than anything.

I’d not been convinced, at the time, that Harrison had really thought we’d be any better. He had a world-weary air about him that seemed to suggest otherwise. John’s words about last-chance saloon came flooding back. Were Mike and I considered to be Justin’s? Might our first placement be already doomed to failure?

I tried to dismiss the idea, telling myself I was being silly. We were last-chance-saloon fosterers – that was the whole point of the programme we were there to implement. But looking at Harrison now I sensed little had changed. That Harrison wasn’t holding out a lot of hope, deep down. Just needed somewhere to place the child, and fast.

‘Come on in,’ Mike said warmly, standing aside to let them all enter. Justin did so with a fair degree of confidence compared with his last visit, I noticed, pulling Harrison along behind him into the living room.

‘Is that all he’s got?’ I asked Harrison, following them, and gesturing to Justin’s single battered suitcase. Yes it was big, but it still seemed very little in the scheme of things. Could it really contain all he had in the whole world?

‘Um … er, yes,’ Harrison replied, looking slightly flustered by my question. He seemed preoccupied with an agenda of his own.

And he was. ‘I don’t have much time, I’m afraid,’ he told us. ‘We’re going to have to get the paperwork sorted out quickly, as I have to be somewhere else pretty soon … but you’re alright,’ he said, turning to Justin, who’d now sat down on the sofa. ‘Looking forward to it, son, aren’t you?’

Justin nodded, and managed to come up with a wonky half-smile. ‘Is it okay if I put the telly on?’ he asked me.

‘Course,’ I said, happy to see he really did seem okay, and so much more relaxed than he’d been with me last time. I smiled, feeling the tension drain away from me a little too. ‘Just not too loud, though, okay?’

Harrison, on the other hand, was making me cross. ‘Shall we go into the kitchen to complete the forms?’ he asked me, visibly anxious to be making a move out through the door. It was as if he really couldn’t wait to leave.

‘Only one suitcase,’ I persisted, as I led him through to the kitchen, while Mike went to show Justin how to work the TV remotes. ‘I’d have thought a child who’d been in care as long as he has would have amassed loads and loads of stuff.’ I did, too. This wasn’t just whimsical thinking on my part. One of the things we’d covered during training was about kids in care and their various possessions. Kids coming straight from a bad home environment often have very little. Neglected and abused they often have owned very few things, and, in many cases, what little they do have tends to be hung on to by their families. Children already in care, on the other hand, do have possessions, often lots of them, because carers are given funds with which to buy them.

Harrison seemed irritated at being sidetracked from his paperwork. ‘Yes, well,’ he said, shuffling them. ‘Justin doesn’t really do “looking after things”. Hence he travels light. So, then. Here are the care plans …’

We went through them, and it was almost as if we were purchasing a car and he was the harried salesman handing us the log book, the deal done. I offered drinks but, no, he really did have to get away, and to be honest I was happy to see the back of him. His attitude towards the whole business of handing over Justin was getting up my nose every bit as much as his crumpled-up suit and musty smell.

Justin came into the kitchen immediately Harrison had left, his expression looking relaxed for the first time since we’d met. He was quite a stocky boy. Tall for his age, too. I’m five feet tall and he was only half a head shorter. He had thick, coarse blond hair, which seemed to grow upwards from his scalp, rather like a character in a cartoon who’s just been electrocuted. And he was smiling now, which immediately softened his stony features. He wasn’t an unattractive boy when he wasn’t on his guard. One job, I mused, would be to work on that smile of his. And, hopefully, soon see much more of it.

‘I’m glad he’s gone,’ he said to me, matter of factly. ‘Is it nearly dinner time yet?’

I looked at the kitchen clock. It was only just coming up to eleven-thirty in the morning. ‘Well,’ I said. ‘I suppose we could always have an early dinner, if you’re hungry …’

He shook his head ‘Oh, I’m not. I just want to know what time we’re having it,’ he answered, in the same straightforward tone. ‘Oh, and what we’re having.’

‘What we’re having?’

Now he nodded at me. ‘Yes.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘if you can hang on just for a little bit longer, I was going to phone my daughter Riley and my son Kieron – they’re both really looking forward to meeting you, Justin. And we’ll just be having a pasta bake, or something.’

‘Twelve, then?’ Now Justin did begin to look a bit flustered. ‘And will it be pasta bake? Or might it be something else?’

‘What was all that about?’ asked Mike, once I’d reassured Justin that, yes, it would be twelve and it would definitely be pasta bake, and, satisfied now, he’d gone back to the living room. Mike chuckled. ‘I’m surprised you didn’t offer him a menu!’

It was good to hear my husband’s familiar and reassuring words – the sound of sanity, the sound of normality. Probably just what this child needed in his life. But, just to be on the safe side I set to work on our unexpectedly early lunch anyway, while Mike went to call Kieron and Riley and tell them the coast was clear. We’d arranged for them to come only once Justin was safely with us, in order that we didn’t overwhelm him.