Полная версия:

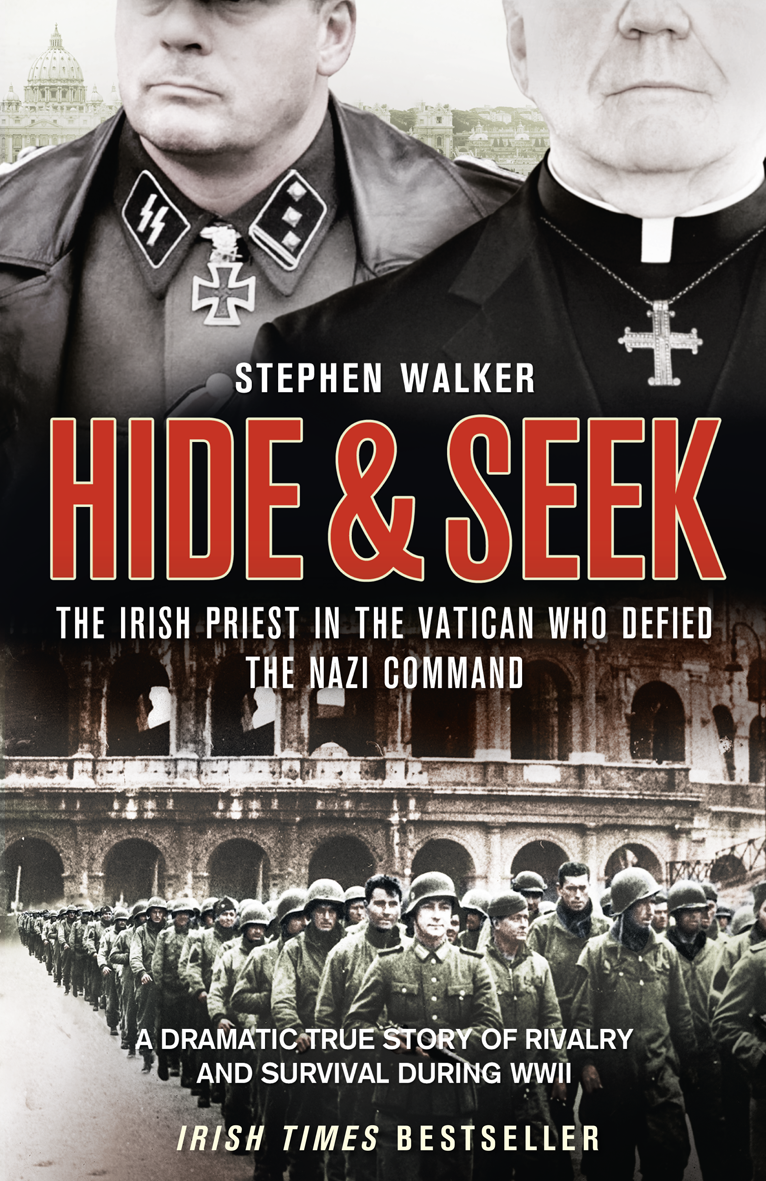

Hide and Seek: The Irish Priest in the Vatican who Defied the Nazi Command. The dramatic true story of rivalry and survival during WWII.

STEPHEN WALKER

HIDE & SEEK

THE IRISH PRIEST IN THE VATICAN WHO DEFIED

THE NAZI COMMAND

THE DRAMATIC TRUE STORY OF RIVALRY

AND SURVIVAL DURING WWII

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter 1 - APPOINTMENT TO KILL

Chapter 2 - DESTINATION ITALY

Chapter 3 - ROME IS HOME

Chapter 4 - SECRETS AND SPIES

Chapter 5 - THE END OF MUSSOLINI

Chapter 6 - OPERATION ESCAPE

Chapter 7 - OCCUPATION

Chapter 8 - TARGET O’FLAHERTY

Chapter 9 - CLOSING THE NET

Chapter 10 - RAIDS AND ARRESTS

Chapter 11 - RESISTANCE AND REVENGE

Chapter 12 - MASSACRE

Chapter 13 - CLAMPDOWN

Chapter 14 - LIBERATION

Chapter 15 - CONVICTION AND CONVERSION

Chapter 16 - KERRY CALLING

Chapter 17 - DEAR HERBERT

Chapter 18 - THE GREAT ESCAPE

Chapter 19 - GOODBYE

Chapter 20 - ROME REVISITED

Picture Section

Notes and Sources

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

14 August 1977

At the military hospital everything was quiet. In the small hours those tasked with watching the patients had little to do. During the day the building was a different place. Then, the corridors and rooms which looked out towards the Colosseum were alive with the sound of people. At night the atmosphere seemed almost reverential and, for those watching the clock until the sun rose, the pace of life was slow.

It was a holiday week in August. From the windows of the complex on the Caelian Hill, night staff could look down on the lights of Rome. The city beneath was asleep, unaware of the drama that was about to unfold.

After midnight, in a room on the third floor, Anneliese, a blonde-haired woman, was spending time with her elderly husband, who was being treated for cancer. The pair were about to embark on the most dramatic hours of their married lives.

For a few moments they stood by the open window. Outside, apart from the sound of an occasional passing car, the night was still. Then the plan began in earnest. Carefully Anneliese manoeuvred her frail husband, dressed in his best suit, towards the doorway. He was skeletal, weighing not much more than seven stone.

Gently she shuffled him across the floor holding his arm as they moved towards the landing. Weeks of planning were now at risk as she made her way down to the ground floor. Holding him close, Anneliese helped her husband negotiate each step. On the ground floor the guard was not around so they quickly made their way outside. Then they made their way to a hire car which had been parked close to the building. She told him to get into the back of the car and lie down and when he was inside she covered him with a blanket.

She put her bags in the car alongside some fresh flowers, turned on the car stereo, lit a cigarette, and drove slowly to the main gate. With her passenger well hidden, she approached the security barrier, the sounds of the radio filling the air. Her early-morning departure did little to raise suspicions. The staff were used to seeing her coming and going at all hours, and she had built up a friendly rapport with most of the hospital workers. She had planned everything and as usual had left a bottle of good German wine for one of the guards. She had also told the gate staff what time she would be leaving. If she could make her visit seem normal she knew her plan had a good chance of succeeding.

In her husband’s empty bed a pillow had been placed strategically to fool anyone who might casually glance through the window of his room. A note handwritten in Italian, saying, ‘Please not disturb me before 10 a.m.’ was stuck on his door. The instruction was intended to ward off enquiring nurses and buy much-needed escape time. A friendly guard approached the car, as he often did when he saw Frau Kappler. He stopped to practise his German, smiled, and began talking. Another soldier, keen to while away the boredom of night duty, sauntered over for a chat.

On any other night the visitor would have relished the conversation. Tonight was different. Even though she was in a hurry and nervous, she knew she had to remain calm. However, the guards were in no hurry to wave her on. Had they spotted something? Would they suddenly decide to search the car? Had someone seen her husband escape and tipped them off?

Anneliese desperately wanted to leave quickly and told the guards she was in a hurry because she needed to get some medicine. At last the barrier was opened. She drove away from the hospital along Via Druso and past the ruins of the ancient baths. Rome was quiet. She stopped briefly and asked her husband if he was all right. ‘Yes, everything is fine,’ came the muffled reply. There was little traffic and she quickly made for the Grand Hotel. There she met her son. She led him to the back of the car and for the first time in his life he saw his stepfather as a free man.

Hours later, when Rome awoke, the city’s most notorious prisoner was declared missing. By then Herbert Kappler had been driven out of the country by car. His driver was his German wife Anneliese, who had married him in prison and had now helped him to freedom. By mid-morning the most wanted man in Italy was heading for a safe house in West Germany. After over thirty years in custody the former Nazi officer was free. Defying life imprisonment for war crimes, he had masterminded a great escape, from the very city he had terrorized as a Gestapo chief some three decades earlier. The hunter was now the hunted.

Chapter One APPOINTMENT TO KILL

‘I don’t want to see him alive again’

Herbert Kappler plots to kill Hugh O’Flaherty

Rome, 1944

Standing alone, six feet two inches tall, weighing nearly fifteen stone, and dressed in his distinctive black and red clerical vestments – most other priests wore only black – Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty was easy to spot. Every day the bespectacled Irishman stood and surveyed the evening scene as Romans went about their daily business. Around him, people made their way to and from work. Some chatted in a leisurely fashion with friends, others, maybe late for appointments, hurried along looking anxious. From his vantage point on the top step that led to St Peter’s Basilica, the monsignor could look out over St Peter’s Square. When the weather was good it was a perfect place to watch the day end.

Cradling his breviary, O’Flaherty would read and occasionally look up and watch as the Vatican buzzed with life. His daily devotion was an act of faith but it was also a display of defiance. And across the piazza his behaviour was being watched carefully. Beyond the white line that had been painted around the cobbled square to mark the Holy See’s neutral territory, Rome’s rulers looked on. Through field binoculars, armed German paratroops studied the priest. They were tasked to watch his every move. Each day the routine continued. O’Flaherty stood and looked out at his observers, who in turn carefully noted all his movements.

This was the monsignor’s territory. A Vatican veteran, O’Flaherty had first graced Rome’s streets in 1922 and was a well-known figure throughout the city. He was hundreds of miles from his birthplace, but he felt completely at home. St Peter’s Square was his open-air office. Nuns and priests would pass by and say a quick hello; others would pause and stop for a longer chat. To the casual observer these meetings and encounters seemed normal and harmless. In reality they were part of O’Flaherty’s operation to gather information and pass messages and money on to those harbouring Allied servicemen.

The vantage point was well chosen. From the steps O’Flaherty could see and be seen. He could keep a close eye on German soldiers at the Vatican’s boundary, by Bernini’s magnificent colonnade. The ever-present Swiss Guards, the Vatican’s loyal protectors, could quickly intervene if trouble arose. From his nearby study window Pope Pius XII could also look down and see the Irishman. It was a perfect spot.

Home to emperors, kings and cardinals, Rome had witnessed over 2,000 years of history. In 1944 it was a dangerous place. The final years of the Second World War were dark days of violence, fear and hunger. Rome was a racial and political mix: a world of German Nazis, Italian fascists and Resistance fighters, spies, diplomats, Catholics and Jews. Into this arena arrived British, American and French servicemen, escapees from Italian prisoner-of-war camps. The Allied landings in the south of the country had caused Italians there to surrender unconditionally and many POWs were simply walking out of the unguarded camps and making their way through the countryside. It was the biggest mass escape in history, but, without maps or guidance, many didn’t know where to go. Encouraged by BBC radio, some set out for the Vatican on the basis that it was free from Nazi interference. Many were caught quickly by the Germans, rounded up and transported to prison camps in Germany. Those who made it to Rome were hoping to be offered shelter by a secret underground unit headed by Monsignor O’Flaherty. Even though the Germans controlled the city, uncovering the Allied escape organization was proving very difficult for them because the Vatican was beyond their control. By the spring of 1944 the struggle was becoming increasingly personal.

One March morning a dark car pulled up at the entrance to St Peter’s Square and from it emerged three men. Two plain-clothed members of the Gestapo accompanied a suave, black-booted figure in his late thirties. With blue eyes, fair hair, and a three-inch duelling scar on his cheek, Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler was the face of the Nazis in Rome. The lieutenant colonel had a reputation for ruthlessness, and his word was not to be challenged on the city’s streets. An experienced SS officer, he had worked his way through the ranks after showing an early talent for secret police work. Handpicked to lead the Gestapo in Rome, Kappler was articulate, well-spoken and confident. He displayed his loyalty like a badge of honour, wearing on one finger a steel ring decorated with the Death’s Head and swastikas and inscribed ‘To Herbert from his Himmler’. In Rome Kappler was head of the Sicherheitsdienst, or SD, the security service of the SS and the Nazi Party. The SD was originally set up by Reinhard Heydrich and by 1944 it had effectively been merged with the state police and was universally known as the Gestapo.

On this particular morning Kappler hadn’t come to check on his subordinates but had journeyed to the Vatican’s boundary to cast an eye over his opponent and make final preparations for a kidnap. The target was Monsignor O’Flaherty.

The 46-year-old priest had become the organizer of the Allied escape operation in Rome by chance rather than by design. In the summer of 1943 a British soldier arrived at the Vatican seeking sanctuary and Hugh O’Flaherty helped him find refuge in one of the many Vatican buildings in which he would stay for the duration of the Nazi occupation. It was the start of an initiative which would eventually offer hundreds of men and women shelter and escape from occupied Italy.

A few weeks later three more British soldiers arrived and they too were given accommodation. By September the original trickle of escapees had turned into a flood. That autumn, St Peter’s Square became the main destination for Allied servicemen seeking safe accommodation in Rome, and their contact there was Hugh O’Flaherty.

It was an open secret what was happening inside the Vatican, and soon intelligence reports landed on Kappler’s desk. The Gestapo chief knew what O’Flaherty’s role was and he suspected that the priest was using rooms in the Vatican and other buildings across Rome to hide the escapees. He gave orders that O’Flaherty be followed and that suspected supporters of what came to be known as the Rome Escape Line be kept under surveillance. Raids were routinely carried out on the homes of Italians sympathetic to the Allies, in the hope of catching escaped soldiers, but Kappler was having little success.

By early 1944 Herbert Kappler and Hugh O’Flaherty were locked in a dangerous game of hide and seek. And it was a battle that the monsignor was winning. Kappler was in no doubt that the Irishman was at the centre of the escape organization, but he needed to catch him red-handed. However, in addition to plotting to stop the monsignor’s activities, he had plenty of other work to do. Kappler and his team spent a great deal of time tracking the movements of members of the Resistance, and the Gestapo were also heavily involved in the interrogation of Rome’s Jews and their deportation to concentration camps.

Kappler could claim to his superiors that he was enacting Nazi rule in Rome and keeping anti-fascist dissent at bay, but he knew he was making little progress with the Allied escape operation. He concluded that the only way to crush the organization was to remove the monsignor, and that meant killing him. Without O’Flaherty he was sure the entire network would crumble.

The daring and controversial move to seize the priest was fraught with difficulties, both political and practical. It would bring Kappler into conflict with the Catholic Church. By March 1944 68-year-old Eugenio Pacelli had just completed his fifth year as Pope Pius XII. He was worried about the impact of the war on the Church and the Vatican State. For much of the conflict the fighting across Europe had seemed distant. However, the arrival of Allied troops in Sicily in July of the previous year, and the air attacks on Rome some months before that, had brought the war to his doorstep.

The German occupation of Rome had created a dilemma for the Pope. Desperate to maintain the independence of the 2,000-year-old Catholic Church, he was fearful that the Nazis would invade the Vatican itself and prevent it functioning. Within days of capturing Rome, Adolf Hitler had promised him that he would respect his sovereignty and protect the Vatican from the fighting. But Pius XII knew Hitler’s guarantee was worthless, since the very presence of German troops in Rome led Allied bombers to regard the Eternal City as a target. The Pope was trying to keep both sides happy in the hope that the Church and its property would survive unscathed. He gained some reassurance from the fact that under international law the Vatican City and all its land and property constituted a neutral state which the Germans were forbidden to enter.

For Kappler this caused some logistical problems, for the kidnap of O’Flaherty would have to be cleverly orchestrated to take place away from Church property. But the Gestapo commander had a plan. It was crude, but he thought it could work. Two plain-clothed SS men would attend early mass and afterwards, as the crowds dispersed, they would simply manhandle the monsignor into German territory. As he squinted across St Peter’s Square at O’Flaherty that sunny March morning, Kappler told the two men, ‘Seize him, hustle him down the steps, and across the line. When you get him into a side-street, free him for a moment. I don’t want to see him alive again and we certainly don’t want any formal trials. He will have been shot while escaping. Understood?’ The instructions seemed straightforward enough.

Kappler then got into his car and was driven out of the square, hoping that he had just looked at Hugh O’Flaherty for the last time. That night, however, just hours before the kidnap was about to occur, the plan began to unravel. In the evening, as he often did, the monsignor was working in his office. Ironically, O’Flaherty lived and worked in the Collegium Teutonicum, the German College, as an official of the Holy Office. Although this building was technically apart from the Vatican, it had some protection under international law. Despite its name, the German College was probably the safest place in Rome from which to run an Allied escape operation as it stood very near the walls of the Vatican and a few hundred yards from the British legation. Church scholars studied at the college, which was under the stewardship of a German rector who was helped by a group of nuns. The place had an international feel to it, and O’Flaherty’s neighbours included a German historian and several Hungarian scholars.

When he first arrived in Rome, O’Flaherty became a student at the Propaganda College, where he became vice rector. He was ordained in 1925 and obtained doctorates in Divinity, Canon Law and Philosophy. While still in his mid-thirties he was promoted to monsignor. This title, bestowed on a number of priests by the Pope, indicated how the upper echelons of the Church viewed the Irishman’s potential.

In the German College, where O’Flaherty would spend most of his career, the accommodation was basic but comfortable. His room had a wardrobe, a few chairs, bookshelves, and a desk always crammed with papers, with his prized typewriter beside them. Nearby stood his golf clubs. A curtain divided off a part of the room and behind it were a single bed and a washbasin. A radio kept the monsignor in touch with world events.

That evening, as O’Flaherty worked at his desk, there was a knock on the door. Seconds later, in came John May. Of medium build, with bushy eyebrows and a shock of dark hair, he worked as a butler for Sir D’Arcy Osborne, the British Minister to the Holy See. May was O’Flaherty’s ‘eyes and ears’, a fixer who had contacts throughout the city and an uncanny ability to find supplies officially deemed unobtainable. May’s success at sourcing rare items in wartime Rome was legendary and O’Flaherty would declare that he was a ‘genius’, the ‘most magnificent scrounger I have ever come across’.

When May called on O’Flaherty, he looked every inch the English manservant, dressed formally in a white shirt, grey tie, black jacket and dark, striped trousers. In his broad cockney accent, May came straight to the point, telling the monsignor what he had just discovered from a contact who had access to Kappler’s plans. Having revealed details of the kidnap operation, he insisted that the monsignor should avoid the next morning’s early mass and disappear from view for a few days. O’Flaherty, who had been a boxer in his younger days, dismissed his visitor’s concern and responded characteristically: ‘So long as they don’t use guns I can tackle any two or three of them with ease. Though a scrap would be a bit undignified on the very steps of St Peter’s itself, would it not?’

The next day May arrived at mass in good time, keen to make sure the kidnap attempt would be foiled. As expected, two SS men sat in the congregation and tried to blend in, unaware that their hosts had prepared a welcome for them. Even though the would-be kidnappers were dressed in plain clothes, they stood out from other church-goers. Throughout mass May kept his eyes on them at all times. When the service ended, the worshippers rose and slowly made their way towards the exits. As the crowd moved towards the daylight that streamed in from the square, several Vatican gendarmes suddenly appeared at the shoulders of the SS men. Outnumbered, the unwelcome visitors were then ushered outside into the morning air, past their intended victim, who was standing close to the door. The monsignor simply watched as the two men were bundled into a side-street and disappeared from view.

It was over. O’Flaherty had outfoxed his rival.

Soon afterwards Kappler was informed that the kidnapping had not succeeded. The battle against the escape organization would continue, but he knew he would need to adopt new tactics. For a man so used to getting things his own way, the failure to remove O’Flaherty from the scene was a rare setback.

Kappler controlled the city from the former offices of the German embassy’s cultural section. Number 20 Via Tasso housed the Gestapo headquarters as well as a prison and interrogation centre, and all over Rome the address spelled police brutality and torture. Here partisans, Jews, communists, gypsies and those who harboured Allied soldiers were interrogated and physically abused. Few came out of Via Tasso unscathed.

Chapter Two DESTINATION ITALY

‘Catholicity makes us pure-minded,

charitable, truthful and generous’

Hugh O’Flaherty

September 1943

In the four years during which Herbert Kappler had lived in Rome he had come to love the city. He felt at home, so comfortable in fact that he encouraged his parents to move there from Germany. Well-read and politically literate, he knew much about his hosts, having studied Italian history. But he was a loner, with few friends, and was trapped in an unhappy marriage. Hoping to divorce his wife, he meanwhile embarked on a series of extramarital affairs. During his time in Rome he would have a string of mistresses, among them a Dutch woman who worked alongside him as an intelligence agent.

Outside work, Kappler’s interests included growing roses, walking his dogs, and photography. He also enjoyed good food and had a penchant for collecting Etruscan vases. He loved to spend time with his adopted son Wolfgang, who was a product of the Lebensborn programme, a Nazi social experiment where children were procreated by Germans deemed to be of pure Aryan stock. The project had the blessing of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, who encouraged his officers to have children with true Aryan women.

Born into a middle-class family in Stuttgart in September 1907, as a young man Kappler showed little interest in a career in the police or the military. After secondary school he wanted to learn a trade, so he studied to be an electrician and obtained jobs with various firms. By his mid-twenties he had decided that his future lay elsewhere. In the early 1930s Germany was undergoing enormous social and political change. The Nazi Party was on the rise and Kappler was becoming increasingly attracted to its ideals.

In August 1931 he joined the Sturmabteilung, or SA, a paramilitary group which had a key role in the Nazi Party and played an important part in Hitler’s rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. However, when Hitler seized control of Germany in January 1933, banning political opposition and turning the country into a one-party state, the Schutzstaffel, or SS, came to prominence and would be placed under the control of Heinrich Himmler. SS members generally came from middle-class backgrounds whereas the SA had a more working-class membership. In December 1932 Herbert Kappler made the move to the SS.

As the world around Kappler was changing, so too was his personal life. In September 1934 he married 27-year-old Leonore Janns, a native of Heilbronn, and they took an apartment in Stuttgart.

With German rearmament in full swing, Kappler was called up to complete military training three times between the summer of 1935 and the autumn of 1936. By now he had secured his first promotion, to SS-Scharführer (sergeant), and worked in Stuttgart’s main Gestapo office. His potential was spotted by his superiors, among them Reinhard Heydrich, who, as head of the Gestapo from April 1934, was already a key figure in the Nazi regime. This connection in particular would help Kappler later in his career.

Another promotion followed for the ambitious Kappler and as an SS-Oberscharführer (staff sergeant) he was later selected to attend the Sicherheitspolizei, or Security Police, leadership school in Berlin, becoming the first non-Prussian to graduate from the institution. Now he was a Criminal Commissioner and clearly destined for higher things. He was fast-tracked and shortly before the Second World War broke out he was posted to Innsbruck, which, after the Anschluss, was within Hitler’s Reich. Kappler’s work in Austria caught the attention of senior military figures in Berlin and he had soon established a reputation as a hardworking, loyal Nazi who acted swiftly against opponents. Not surprisingly, his stay in Austria was brief.