Полная версия:

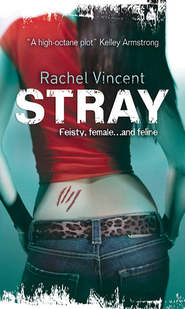

Stray

STRAY

My heart pounding, I stepped out of the alley, half expecting to be struck by lightning or hit by a runaway train. Nothing happened, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong. I took another step, my eyes wide to let in all of the available light. Still nothing happened.

I was feeling foolish now, chasing a stranger down a dark alley at night, like some bimbo from a bad horror film. In the movies, this was where things always went wrong. A hairy hand would reach out of the shadows and grab the curious-but-brainless heroine around the throat, laughing sadistically while she wasted her last breath on a scream.

The difference between the movies and reality was that in real life, I was the hairy monster, and the only screaming I ever did was in rage. I was about as likely to cry for help as I was to spontaneously combust. If this particular bad guy hadn’t figured that out yet, he was in for a very big surprise.

Find out more about Rachel Vincent by visiting mirabooks. co. uk/rachelvincent and read Rachel’s blog at ubanfantasy.blogspot.com

Coming soon

ROGUE

Also by Rachel Vincent

Shifters series STRAY ROGUE PRIDE PREY SHIFT ALPHA Soul Screamers series MY SOUL TO TAKE MY SOUL TO KEEP MY SOUL TO SAVE MY SOUL TO STEAL IF I DIE BEFORE I WAKE Unbound series BLOOD BOUND SHADOW BOUND And coming soon … OATH BOUND

Stray

Rachel Vincent

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book is a very solitary pursuit. Publishing one is not. It’s a group effort, requiring contributions from many people, with many different areas of expertise. With that in mind, I’d like to thank everyone who worked on Stray during its development: editorial director Dianne Moggy and executive editor Margaret Marbury; in marketing, Ana Movileanu and Stacy Widdrington; art director Erin Craig and designer Sean Kapitain; editorial assistant Adam Wilson, whose contributions behind the scenes should not go unnoticed; and everyone involved in production and sales. Thank you all.

Also, thanks to Ohh, who double-checked my Spanish, without laughing at my mistakes.

Thanks to my editor, the fabulous Mary-Theresa Hussey, whose patience with me and faith in my story are directly responsible for putting this book on the shelf. Thanks to literary agent extraordinaire Miriam Kriss for being so incredibly good at her job. For answering my questions and calming me down. For giving me confidence and pride in my work. In short, thanks for selling my books.

And finally, I owe a huge debt of gratitude – and a big hug – to Kim Harrison, the world’s greatest mentor, for lending her wisdom, her experience and her time to a newbie writer in need of guidance. For teaching me more than I ever thought possible, and more than I could ever express. And most of all, thanks, Kim, for taking me seriously.

To my No.1 fan, the love of my life, for endless support and encouragement. For providing me with the time and the space I needed to make my dream come true. And most of all, for daring me to finally put my hands on the keyboard, and the words on the page.

This never would have happened without you.

One

The moment the door opened I knew an ass-kicking was inevitable. Whether I’d be giving it or receiving it was still a bit of a mystery.

The smell hit me as I left the air-conditioned comfort of the language building for the heat of another north-central Texas summer, tugging my backpack higher on my shoulder as I squinted into the sunset. A step behind me, my roommate, Sammi, was ranting about the guest lecturer’s discriminatory view of women’s contributions to nineteenth-century literature. I’d been about to play devil’s advocate, just for the hell of it, when a shift in the evening breeze stopped me where I stood, on the top step of the narrow front porch.

My argument forgotten, I froze, scanning the shadowy quad for the source of the unmistakable scent. Visually, nothing was out of the ordinary: just small groups of summer students talking on their way to and from the dorms. Human students. But what I smelled wasn’t human. It wasn’t even close.

Absorbed in her rant, Sammi didn’t realize I’d stopped. She walked right into me, cursing loud enough to draw stares when her binder fell out of her hand and popped open on the ground, littering the steps with loose-leaf paper.

“I could use a little notice next time you plan on zoning out, Faythe,” she snapped, bending to gather up her notes. Grunts and more colorful words issued from behind her, where our fellow grad students were stalled by our pedestrian traffic jam. Lit majors are not known for watching where they’re going; most of us walk with our eyes in a book instead of on the path ahead.

“Sorry.” I knelt to help her, snatching a sheet of paper from the concrete before the student behind me could stomp on it. Standing, I took the steps two at a time, following Sammi to a brick half wall jutting from the porch. Still talking, she set her binder on the ledge and began methodically reorganizing her notes, completely oblivious to the scent, as humans always were. I barely heard her incessant chatter as she worked.

My nostrils flared slightly to take in more of the smell as I turned my face into the breeze. There. Across the quad, in the alley between the physics building and Curry Hall.

My fist clenched around the strap of my backpack and my teeth ground together. He wasn’t supposed to be here. None of them were supposed to be here. My father had promised.

I’d always known they were watching me, in spite of my father’s agreement not to interfere in my life. On occasion, I’d spot a too-bright eye in the crowd at a football game, or notice a familiar profile in line at the food court. And rarely—only twice before in five years—I caught a distinctive scent on the air, like the taste of my childhood, sweet and familiar, but with a bitter aftertaste. The smell was faint and tauntingly intimate. And completely unwelcome.

They were subtle, all those glimpses, those hints that my life wasn’t as private as we all pretended. Daddy’s spies faded silently into crowds and shadows because they wanted to be seen no more than I wanted to see them.

But this one was different. He wanted me to see him. Even worse—he wasn’t one of Daddy’s.

“…that her ideas are somehow less important because she had ovaries instead of testes is beyond chauvinistic. It’s barbaric. Someone should…Faythe?” Sammi nudged me with her newly restored notebook. “You okay? You look like you just saw a ghost.”

No, I hadn’t seen a ghost. I’d smelled a cat.

“I’m feeling a little sick to my stomach.” I grimaced only long enough to be convincing. “I’m going to go lie down. Will you apologize to the group for me?”

She frowned. “Faythe, this was your idea.”

“I know.” I nodded, thinking of the four other M.A. candidates already gathered around their copies of Love’s Labours Lost in the library. “Tell everyone I’ll be there next week. I swear.”

“Okay,” she said with a shrug of her bare, freckled shoulders. “It’s your grade.” Seconds later, Sammi was just another denim-clad student on the sidewalk, completely oblivious to what lurked in the late-evening shadows thirty yards away.

I left the concrete path to cut across the quad, struggling to keep anger from showing on my face. Several feet from the sidewalk, I stepped on my shoelace, giving myself time to come up with a plan of action as I retied it. Kneeling, I kept one eye on the alley, watching for a glimpse of the trespasser. This wasn’t supposed to happen. In my entire twenty-three years, I’d never heard of a stray getting this far into our territory without being caught. It simply wasn’t possible.

Yet there he was, hiding just out of sight in the alley. Like a coward.

I could have called my father to report the intruder. I probably should have called him, so he could send the designated spy-of-the-day to take care of the problem. But calling would necessitate speaking to my father, which I made a point to avoid at all costs. My only other course of action was to scare the stray off on my own, then dutifully report the incident the next time I caught one of the guys watching me. No big deal. Strays were loners, and typically as skittish as deer when confronted. They always ran from Pride cats because we always worked in pairs, at the very least.

Except for me.

But the stray wouldn’t know I had no backup. Hell, I probably did have backup. Thanks to my father’s paranoia, I was never really alone. True, I hadn’t actually seen whoever was on duty today, but that didn’t mean anything. I couldn’t always spot them, but they were always there.

Shoe tied, I stood, for once reassured by my father’s overprotective measures. I tossed my bag over one shoulder and ambled toward the alley, doing my best to appear relaxed. As I walked, I searched the quad discreetly, looking for my hidden backup. Whoever he was, he’d finally learned how to hide. Perfect timing.

The sun slipped below the horizon as I approached the alley. In front of Curry Hall, an automatic streetlight flickered to life, buzzing softly. I stopped in the circle of soft yellow light cast on the sidewalk, gathering my nerve.

The stray was probably just curious, and would likely run as soon as he knew I’d seen him. But if he didn’t, I’d have to scare him off through other, more hands-on means. Unlike most of my fellow tabby cats, I knew how to fight; my father had made sure of that. Unfortunately, I’d never made the jump from theory to practice, except against my brothers. Sure, I could hold my own with them, but I hadn’t sparred in years, and this didn’t feel like a very good time to test skills still unproven in the real world.

It’s not too late to call in the cavalry, I thought, patting the slim cell phone in my pocket. Except that it was. Every time I spoke to my father, he came up with a new excuse to call me home. This time he wouldn’t even need to make one up. I’d have to handle the problem myself.

My resolve as stiff as my spine, I stepped out of the light and into the darkness.

Heart pounding, I entered the alley, tightening my grip on my bag as if it were the handle of a sword. Or maybe the corner of a security blanket. I sniffed the air. He was still there; I could smell him. But now that I was closer to the source, I detected something strange in his scent—something even more out of place than the odor of a stray deep inside my Pride’s territory. Whoever this trespasser was, he wasn’t local. There was a distinctive foreign nuance to his scent. Exotic. Spicy, compared to the blandly familiar base scent of my fellow American cats.

My pulse throbbed in my throat. Foreign. Shit. I was in over my head.

I was digging in my pocket for my phone when something clattered to the ground farther down the alley. I froze, straining to see in the dark, but with my human eyes, it was a lost cause. Without Shifting, I couldn’t make out anything but vague outlines and deep shadows. Unfortunately, Shifting wasn’t an option at that moment. It would take too long, and I’d be defenseless during the transition.

Human form it is.

I glanced quickly behind me, looking for signs of life from the quad. It was empty now, as far as I could tell. There were no potential witnesses; everyone with half a brain was either studying or partying. So why was I playing hide-and-seek after dark with an unidentified stray?

My muscles tense and my ears on alert, I started down the alley. Four steps later, I stepped through a broken tennis racket and stumbled into a rusty Dumpster. My bag thumped to the ground as my head hit the side of the trash receptacle, ringing it like an oversize gong.

Smooth, Faythe, I thought, the metallic thrum still echoing in my ears.

I bent over to pick up my bag, and a darting motion up ahead caught my eye. The stray—in human form, thankfully—ran from the mouth of the alley into the parking lot behind Curry Hall, his feet unnaturally silent on the asphalt. Pale moonlight shined on a head full of dark, glossy curls as he ran.

Instinct overrode my fear and caution. Adrenaline flooded my veins. I tossed my bag over my shoulder and sprinted down the center of the alley. The stray had fled, as I’d hoped he would, and the feline part of my brain demanded I follow. When mice run, cats give chase.

At the end of the alley, I paused, staring at the parking lot. It was empty, but for an old, busted up Lincoln with a rusty headlight. The stray was gone. How the hell had he gotten away so fast?

A prickly feeling started at the base of my neck, raising tiny hairs the length of my spine. Every security light in the lot was unlit. They were supposed to be automatic, like the ones in the quad. Without the familiar buzz and the reassuring flood of incandescent light, the parking lot was an unbroken sea of dark asphalt, eerily quiet and disturbingly calm.

My heart pounding, I stepped out of the alley, half expecting to be struck by lightning or hit by a runaway train. Nothing happened, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong. I took another step, my eyes wide to let in all of the available light. Still nothing happened.

I was feeling foolish now, chasing a stranger down a dark alley at night, like some bimbo from a bad horror film. In the movies, this was where things always went wrong. A hairy hand would reach out of the shadows and grab the curious-but-brainless heroine around the throat, laughing sadistically while she wasted her last breath on a scream.

The difference between the movies and reality was that in real life, I was the hairy monster, and the only screaming I ever did was in rage. I was about as likely to cry for help as I was to spontaneously combust. If this particular bad guy hadn’t figured that out yet, he was in for a very big surprise.

Emboldened by my own mental pep talk, I took another step.

The distinctive foreign scent washed over me, and my pulse jumped, but I never saw the kick coming.

Suddenly I was staring at the ground, doubled over from the pain in my stomach and fighting for the strength to suck in my next breath.

My bag fell to the ground at my feet. A pair of black, army-style boots stepped into sight, and the smell of stray intensified. I looked up just in time to register dark eyes and a creepy smile before his right fist shot out toward me. My arms flew up to block the blow, but his other arm was already flying. His left fist slammed into the right side of my chest.

Fresh pain burst to life in my rib cage, radiating in a widening circle. One hand pressed to my side, I struggled to stand up straight, panicked when I couldn’t.

An ugly cackling laugh clawed my inner chalkboard and pissed me off. This was my campus, and my Pride’s territory. He was the outsider, and it was time he learned how Pride cats dealt with intruders.

He pulled his fist back for another blow, but this time I was ready. Ignoring the pain in my side, I lunged to my right, reaching for a handful of his hair. My fingers tangled in a thick clump of curls. I shoved his head down and brought my knee up. The two connected. Bone crunched. Something warm and wet soaked through my jeans. The scent of fresh blood saturated the air, and I smiled.

Ah, memories…

The stray jerked his head free of my grip and lurched out of reach, leaving me several damp curls as souvenirs. Wiping blood from his broken nose, he growled deep inside his throat, a sound like the muted rumble of an engine.

“You should really thank me,” I said, a little impressed by the damage I’d caused. “Trust me. It’s an improvement.”

“Jodienda puta!” he said, spitting a mouthful of blood on the concrete.

Spanish? I was pretty sure it wasn’t a compliment. “Yeah, well, back at ’cha. Get your mangy ass out of here before I decide a warning isn’t enough!”

Instead of complying, he aimed his next shot for my face. I tried to dodge the punch, but couldn’t quite move fast enough. His fist slammed into the side of my skull.

I reeled from the blow, fireworks going off behind my eyelids. My head throbbed like a migraine on steroids. The whole world seemed to spin just for me.

At the edge of my graying vision, the stray fumbled for something in his pocket, cursing beneath his breath in a Spanish-like language I couldn’t quite identify. His arm shot out again. Not steady enough yet to move, I braced myself for impact. The blow never came. He grabbed my arm and pulled trying to haul me away from the deserted student center.

What the hell? When confronted by a Pride cat, any stray in possession of two brain cells to rub together would take off with his fur standing on end. After what I’d done to his face, this one should have run screaming from me in terror. It was because I was a girl, I knew it. If I were a tomcat instead of a tabby, he’d already be halfway to Mexico.

I hate it when men aren’t afraid of me. It reminds me of home.

Backpedaling to keep from falling, I tried to yank my arm from his grip. It didn’t work. Angry now, I swung my free fist around, smashing it into his skull. He grunted and dropped my arm.

I rushed toward the alley and snatched my bag from the ground. The stray’s footsteps pounded behind me. I tightened my grip and whirled around, swinging the pack by its straps. It smashed into his left ear. His head snapped back and to the side. More blood flew from his nose, splattering the parking lot with dark droplets. The stray fell on his ass on the concrete, one hand covering the side of his head. He stared at me in astonishment. I laughed. Apparently the complete works of Shakespeare packed quite a wallop.

To think, my mother said I’d never find use for an English degree. Ha! I’d like to see her knock someone silly with an apron and a cookie press.

“Puta loco,” the stray muttered, digging in his pocket again as he scrambled to his feet. Without another word—or even a glance—he took off across the parking lot toward the Lincoln. Seconds later, tires screeched as he peeled from the lot, heading south on Welch Street.

“Adios!” I watched him go, sore but pleased. Surely after that, Daddy will have to admit I can take care of myself.

Panting from exertion, I threw my bag over my shoulder and glanced at my watch. Damn. Sammi would be home from study group soon, and she’d be horrified by my bloody jeans and brand-new bruises. I’d have to change before she got in. Unfortunately, keeping bruises hidden from Andrew would be much harder. Dating humans could be a real pain in the ass sometimes.

Still picturing the intruder’s mutilated face, I turned back toward the alley—and came face-to-face with another stray. Well, face-to-head-shrouded-in-shadow, anyway. He stood five feet away, just out of reach of the pale moonlight, and I could see nothing but the hands hanging empty at his sides. I knew at a glance that they could do serious damage, even clenched around nothing but air.

I didn’t need to smell this stray to know who he was; his scent was as familiar to me as my own. Marc. My father’s second-in-command. Daddy had never sent Marc before—not once in five years. Something was wrong.

Tension crept up my back and down my arms, curling my hands into fists. I gritted my teeth to hold in a shriek of fury; the last thing I needed was to call attention to myself. Human do-gooders were always out to save the world, but few of them had any idea what kind of a world they really lived in.

I stepped slowly toward Marc, letting my backpack slide down my arm to the ground. I fixed my gaze on the shadow hiding his gold-flecked eyes. He didn’t move. I came closer, my pulse pounding in my throat. He raised his left hand, reaching out to me. I slapped it away.

Shifting my weight to my left leg, I let my right foot fly, hitting him in the chest with a high side kick. Grunting, he stumbled into the alley. His heel hit the corner of a wooden crate and he fell on his ass on a damp cardboard box.

“Faythe, it’s me!”

“I know who the hell you are.” I came toward him with my hands on my hips. “Why do you think I kicked you?” I pulled my right foot back, prepared to let it fly again. His arm shot out almost too fast to see, and his hand wrapped around my left ankle. He pulled me off my feet with one tug. I landed on my rear beside him, on a split-open trash bag.

“Damn it, Marc, I’m sitting in this morning’s fresh-squeezed orange peels.”

He chuckled, crossing his arms over a black T-shirt, clinging to well-defined pecs. “You nearly broke my ribs.”

“You’ll live.”

“No thanks to you.” He pushed himself awkwardly to his feet and held out a hand for me. When I ignored it, he rolled his eyes and pulled me up by my wrist. “What’s with the kung fu routine, anyway?”

I yanked my arm from his grip and stepped back, glaring at him as I wiped orange pulp from the seat of my pants. “It’s tae kwon do, and you damn well know it.” We’d trained together—alongside all four of my brothers—for nearly a decade. “You’re lucky I didn’t kick your face in. What took you so fucking long? If you guys are going to hang around without permission, you might as well make yourselves useful when I’m in mortal peril. That is what Daddy’s paying you for.”

“You handled yourself fine.”

“Like you’d know. I bet he was halfway to his car by the time you got here.”

“Only a quarter of the way,” Marc said, grinning. “Anyway, I was the one in real danger. I got cornered by a pack of wild sorority sisters in the food court. Apparently it’s mating season.”

I frowned at him, picturing a throng of girls in matching pink T-shirts giggling as they vied for his attention. I could have told them they were wasting their time. Marc had no use for human women, especially silly, flirtatious trophy wives–in–training. His dark curls and exotic brownish-gold eyes had always garnered him more attention than he really wanted. And this time they’d kept him from doing his job.

“You’re a worthless bastard,” I said, not quite able to forgive him for being late, even though I didn’t want him there in the first place.

“And you’re a callous bitch.” He smiled, completely unaffected by my heartfelt insult. “We’re a matched set.”

I groaned. At least we were back in familiar territory. And it was kind of nice to see him too, though I would never have admitted it.

Turning my back on him, I grabbed my book bag and stomped to the other end of the alley, then into the empty quad. Marc followed closely, murmuring beneath his breath in Spanish too fast for me to understand. Memories I’d successfully blocked for years came tumbling to the front of my mind, triggered by his whispered rant. He’d been doing that for as long as I could remember.

My patience long gone, I stopped in front of the student center in the same circle of light, and whirled around to face Marc. “Hey, you wanna drop back a few paces? Did you forget how spying works? You’re supposed to at least aim for unobtrusive. The others pretty much have it down, but you’re about as inconspicuous as a drag queen at a Girl Scout meeting.” I propped my hands on the hips of my low-rise jeans and scowled up at him, trying to remain unaffected by the thickly lashed eyes staring back at me.

Marc smiled, his expression casual, inviting, and utterly infuriating. “It’s nice to see you too.” A wistful look darted across his face as he glanced at my bare midriff, his gaze moving quickly over my snug red halter top to settle on the barrette nestled in my hair.