Полная версия:

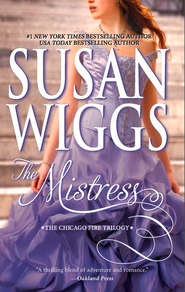

The Mistress

Praise for the novels of Susan Wiggs

“Susan Wiggs paints the details of

human relationships with the finesse of a master.”

—Jodi Picoult, New York Times bestselling author

“Wiggs provides a delicious story for us to savor.”

—Oakland Press on The Mistress

“Susan Wiggs delves deeply into her characters’

hearts and motivations to touch our own.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Mistress

“Once more, Ms. Wiggs demonstrates her ability

to bring readers a story to savor that has them

impatiently awaiting each new novel.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Hostage

“A quiet page-turner that will hold readers

spellbound as the relationships, characters

and story unfold. Fans of historical romances

will naturally flock to this skillfully executed trilogy,

and general women’s fiction readers should

find this story enchanting as well.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Firebrand

“Wiggs is one of our best observers

of stories of the heart. Maybe that is because

she knows how to capture emotion on

virtually every page of every book.”

—Salem Statesman-Journal

“Susan Wiggs writes with bright assurance,

humor and compassion.”

—Luanne Rice, New York Times bestselling author

The Mistress

The Chicago Fire Trilogy

Susan Wiggs

www.mirabooks.co.uk

To my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Marge Green,

who taught me cursive writing

and told me the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Joyce, Betty and Barb, for favors too numerous to count; to friends near and far, including Jamie for brainstorming a trading scam, and Jodi for therapeutic e-mail conversations; thanks to Jill for the Bunco book, and to the wonderful Martha Keenan, who always edits above and beyond the call of duty.

Special thanks to the Chicago Historical Society, one of the richest resources ever to make itself available to a writer.

Also by Susan Wiggs

Contemporary Romances

HOME BEFORE DARK

THE OCEAN BETWEEN US

SUMMER BY THE SEA

TABLE FOR FIVE

LAKESIDE COTTAGE

JUST BREATHE

The Lakeshore Chronicles

SUMMER AT WILLOW LAKE

THE WINTER LODGE

DOCKSIDE

SNOWFALL AT WILLOW LAKE

FIRESIDE

LAKESHORE CHRISTMAS

THE SUMMER HIDEAWAY

Historical Romances

THE LIGHTKEEPER

THE DRIFTER

The Tudor Rose Trilogy

AT THE KING’S COMMAND

THE MAIDEN’S HAND

AT THE QUEEN’S SUMMONS

Chicago Fire Trilogy

THE HOSTAGE

THE MISTRESS

THE FIREBRAND

Calhoun Chronicles

THE CHARM SCHOOL

THE HORSEMASTER’S DAUGHTER

HALFWAY TO HEAVEN

ENCHANTED AFTERNOON

A SUMMER AFFAIR

One dark night,—

when people were in bed,

Old Mrs. Leary lit a lantern in her shed;

The cow kicked it over, winked its eye and

said”There’ll be a hot time

in the old town tonight.”

~Anon.,

quoted in the Chicago Evening Post

The Contact

What is the chief end of man?

—to get rich.

In what way?

—dishonestly if we can;

honestly if we must.

Mark Twain, 1871

The Setup

It was beautiful and simple

as all truly great swindles are.

~O. Henry

Annual income twenty pounds,

annual expenditure nineteen six,

result happiness.

~Charles Dickens

Prologue

Chicago

October 8, 1871

She looked older than her years from a lifetime of toil. The routine struggles of making her way in the world wore on her like the fading dye of her dimity dress. Up at dawn for the milking, feeding the hungry mouths that depended on her for every breath they took, keeping house, seeing to the livestock and navigating the unseen reefs and rocky shoals of everyday living had stolen her youth.

On a hot October night following a hot October day, Catherine O’Leary put the children down early. She washed up after supper, plunging her chapped and chafed hands into the tepid water. A high prairie wind roared through the shantytown that comprised her small world, across the river from the quiet, stately mansions of the grain barons and merchant princes. Her children had learned to sleep despite the boisterous, frequent celebrations of the McLaughlins next door. The neighbors were welcoming a cousin newly arrived from Ireland, and the thin, lively whine of fiddle music flooded through the open windows, causing the walls to vibrate. As she washed, Catherine tapped her sore, bare foot to match the rhythm of hobnail boots on plank floors emanating from the adjacent cottage.

Shadows deepened across the beaten-earth yard leading to the cow barn that housed the source of the family’s livelihood. Her husband was out back now, feeding and watering the animals. The dry, blowing heat caused brown leaves to erupt in restless swirls through the air. The wind picked up, sounding like the chug of a locomotive coming on fast.

Catherine dried her hands on her apron as Patrick returned from the barn, his shoulders bowed with exhaustion. She saw a flicker in the sky, a star winking its eye perhaps, but her attention was all for her husband. This week he had worked hard, laying in supplies for the winter—three tons of timothy hay, another two tons of coal, wood shavings for kindling from Bateham’s Planing Mill. Baking in the arid heat, the shavings curled and rustled when the aggressive wind stirred them. In this heat it was hard to imagine that winter was only weeks away.

She gave Patrick his supper of potatoes and pickled cabbage, wishing he’d had time to eat with her and the children. But families like the O’Learys did not have that luxury. Imagine, sitting down like the Quality, with enough room for everyone around the same table.

She took off her apron and kerchief. Pumping fresh water into the sink, she bathed her face and neck, and finally her sore foot; a cow had stepped on it that morning and she had been limping around all day. She drew the curtains and peeled her bodice to the waist, giving herself a more thorough washing. She braided her thick red hair, then went to check on the children. Scattered like puppies in the restless heat, the little ones lay uncovered on rough sheets she had sprinkled with water to keep them cool. There was another daughter, Kathleen, firstborn and first to leave the reluctant arms of her parents to work as a lady’s maid at Chicago’s finest school for young ladies. Perhaps in the turreted stone building by the lake, Kathleen suffered less from the heat than they did here in the West Division.

Ah, Kathleen, there was a fine young article, Catherine thought fondly. By hook or by crook, she’d make good. The Lord in his wisdom had given her the brains and the looks to do it. She wouldn’t turn out like her mother, overworked, tired, old before her time.

The sounds of revelry next door swelled, then quieted, mingling with the howl of the wind. Through the coarse weave of the sackcloth curtains, Catherine noticed a flash of light in the window.

“Let us to bed, Mother,” her husband said softly. Patrick kissed her and put out the lamp. Settling her weary head on the pillow, she listened to the rustling and breathing of her children. Then she nestled into the strong soft cradle of her husband’s arms, sighed and thought that maybe this was what all the toil was for. This one sweet moment of inexpressible bliss.

A knock at the door drew Catherine O’Leary back from the comfortable edge of sleep. The McLaughlins’ fiddle wailed on and the bodhran thumped out an ancient tribal rhythm. Two of the children awakened and started whispering. Frowning, she propped herself up on one elbow and prodded Patrick. “Are you awake, then?” she asked.

“Aye, just. I’ll see who it is.”

She lay still, hearing the low murmur of masculine voices followed by the sound of the door swishing shut. Her sore foot throbbed heatedly under the thin sheet.

“It was Daniel Sullivan with Father Campbell, come to call,” Patrick said, returning. “I told them we were already abed, and not in a state for entertaining company.”

“God preserve us for turning away a priest,” Catherine said, “but ‘tisn’t he who has to do the milking at dawn.” Feeling guilty for criticizing a priest, she drew aside a corner of the curtain to see the two men leaving.

Daniel often took an evening walk to escape the stifling heat of his cottage, even smaller and more cramped than the O’Leary place. He had one wooden leg, and as he walked along the pine plank sidewalk, his gait had the curious cadence of a heartbeat. He kept his head down, for his wooden leg tended to wedge itself into the cracks between the boards if he wasn’t careful.

She was about to settle back down for the night when she noticed a sweeping gust of wind lifting the priest’s long black cassock, revealing skinny white legs and drawers of a startling green hue. “Now there’s a sight you don’t see every day,” she muttered.

Outside the wooden cottage, high in the hot night sky, a spark from someone’s stove chimney looped and whirled, pushed along by the wind gusting in from the broad and empty Illinois prairie. The spark entered the O’Learys’ barn, where the milk cows and a horse stood tethered with their heads lowered, and a calf slept on a bed of straw.

The glowing ember dropped onto the hay, and the wind fanned it until it bloomed, then burned in a hot, steady circle of orange. The flames spread like spilled kerosene, rushing down and over the bales of hay and lighting the crisp, dry wood shavings. Within moments, a river of fire flowed across the barn floor.

It was full dark the next time Catherine awakened, once again by a knock at the door. More visitors? No, this knocking had the rapid tattoo of alarm. Patrick hurried to answer. Catherine drew aside the tattered curtain divider to look in on the children. Over their sweet, slumbering faces, an eerie glow of light glimmered.

“Sweet Jesus,” she whispered, racing to the window and tearing back the curtain.

A column of flame roared up the side of the barn. Firelight streamed across the yard between house and shed.

Catherine O’Leary opened the cottage door to an inferno. Her husband ran toward her, his face stark in the flame-lit night.

He said what she already knew, voicing the fear that made her heart sink like a stone in her chest: “See to the children. The barn’s afire.”

Chapter One

Under a French gown of emerald silk, Kathleen O’Leary wore homespun bloomers that had seen better days. She told herself not to worry about what lay beneath her sumptuous costume. It was what the world saw on the surface that mattered, particularly tonight.

Next Friday, she would go down on her knees and admit the ruse to Father Campbell in the confessional, but Friday was far away. At the present moment, she meant to enjoy herself entirely, for it was a night of deceptions and she was at its heart.

The mechanical gilt elevator speeding them up to the third-floor salon of the Hotel Royale was only partially responsible for the swift rush of anticipation that tingled along her nerves. She clasped hands with her two companions, Phoebe Palmer and Lucy Hathaway, and gave them a squeeze. “Think we’ll get away with it?” she whispered.

Lucy sent her a dark-eyed wink. “With looks like that, you could get away with robbing the Board of Trade.”

Kathleen would have pinched herself if she hadn’t been holding on so tightly to her friends’ hands. She couldn’t believe she was actually committing such an audacious act. Going to a social affair to which she wasn’t invited. In a dress from Paris that didn’t belong to her. Wearing jewels worth a king’s ransom. To meet people who, if they knew who she really was, would not consider her fit to black their boots.

The bellman pushed up the brake lever and cranked open the door. With only a swift glance, Kathleen recognized him as an Irishman. He had the sturdy features and mild, deferential demeanor of a recent immigrant. Phoebe swept past him, not even seeing the small man.

“Mayor Mason will not be seeking another term,” Phoebe was saying in a breathless voice that seemed fashioned solely for gossip. “Mrs. Wendover is having a flaming love affair with a student at Rush Medical College.” She enumerated the tidbits on her fingers, intent on bringing Kathleen up to date with the guests she was about to meet. “And Mr. Dylan Kennedy is just back from the Continent.”

“Remind me again. Who is Dylan Kennedy?” Lucy asked in a bored voice. She had never been one to be overly impressed by the upper classes—probably because she came from one of the oldest families of the city, and she understood their foibles and flaws.

“Don’t you know?” Phoebe patted a brown curl into place. “He’s only the richest, most handsome man in Chicago. It’s said he came back to look for a wife.” She led the way down the carpeted hall. “He might even begin courting someone in earnest this very night. Isn’t that deliciously romantic?”

“It’s not deliciously anything,” Lucy Hathaway said with a skeptical sniff. “If he needs to pick something, he should go to the cattle auction over at the Union Stockyards.”

Kathleen said nothing, but privately she agreed with Phoebe for once. Dylan Francis Kennedy was delicious. She had glimpsed him a week earlier at a garden party at the Sinclair mansion, where her mistress, Miss Deborah Sinclair, lived when not away at finishing school. Kathleen had stolen a few moments from tending to her duties to look out across the long, groomed garden, and there, by an ornate gazebo, had stood the most wonderful-looking man she had ever seen. In perfectly tailored trousers that hugged his narrow hips, and a charcoal-black frock coat that accentuated the breadth of his shoulders, he had resembled a prince in a romantic story. Of course, it was a glimpse from afar. Up close, he probably wasn’t nearly as…delicious.

She spied a door painted with the words Ladies’ Powder Room and gave Lucy’s hand a tug. “Could we, please?” she said. “I think I need a moment to compose myself.” She spoke very carefully, disguising the soft brogue of her everyday speech.

Phoebe tapped an ivory-ribbed fan smartly on the palm of her gloved hand. “Chickening out?”

“In a pig’s eye,” Kathleen said, a shade of the dreaded brogue slipping out. She was always provoked and challenged by Phoebe Palmer, who belonged to one of Chicago’s leading families. Phoebe, in turn, thought Kathleen far too cheeky and familiar with her betters and did her best to put the maid in her place.

That, in fact, was part of the challenge tonight. Lucy swore Kathleen could pass for a member of the upper crust. Phoebe didn’t believe anyone would be fooled by the daughter of Irish immigrants. Lucy asserted that it would be an interesting social experiment. They had even made a wager on the outcome. Tomorrow night, Crosby’s Opera House was scheduled to open, and the cream of Chicago society would be in attendance. If Kathleen managed to get herself invited, Phoebe would donate one hundred dollars to Lucy’s dearest cause—suffrage for women.

“You can gild that lily all you like,” Phoebe had said to Lucy as they were getting ready for the evening. “But anyone with half a brain will know she’s just a common weed.”

“Half a brain,” Lucy had laughed and whispered in Kathleen’s ear, which burned with a blush. “That leaves out most of the people at the soiree.”

They stepped into the powder room decked with gilt-framed mirrors and softly lit by the whitish glow of gaslight sconces. The three young ladies stood together in front of the tall center mirror—Lucy, with her black hair and merry eyes, Phoebe, haughty and sure of herself, and Kathleen, regarding her reflection anxiously, wondering if the vivid red of her hair and the scattering of freckles over her cheeks and nose would be a dead giveaway. Her long bright ringlets spilled from a set of sterling combs, and the flush of nervousness in her cheeks was not unbecoming. Perhaps she could pull this off after all.

“Lord, but I wish Miss Deborah had come,” she said, leaning forward and turning her head to one side to examine her diamond-and-emerald drop earrings. The costly baubles swayed with an unfamiliar tug. Other than girlish games of dress-up, which she had played with Deborah when she’d first gone to work as a maid at the age of twelve, Kathleen had never worn jewelry in her life. The eldest of five, she had never even received the traditional cross at her First Communion. Her parents simply hadn’t had the money.

“Deborah wasn’t well,” Phoebe reminded her. “Besides, if she had come, then you wouldn’t have had her fabulous gown to wear, or her Tiffany jewels, and you’d be sitting at the school all alone tonight.”

“Cinderella sifting through the ashes,” Kathleen said tartly. “You’d have loved that.”

“Not really,” Phoebe said, and just for a moment her haughty mask fell away. “I do wish you well, Kathleen. Please know that.”

Kathleen was startled by the moment of candor. Perhaps, she thought, there were some things about the upper classes she would never understand. But that had not stopped her from wanting desperately to be one of them. And tonight was the perfect opportunity.

The well-tended young ladies of Miss Emma Wade Boylan’s School received scores of invitations to social events in Chicago. Miss Boylan had a reputation for finishing a young woman with charm and panache, and charging her patrons dearly for the privilege. In return, Miss Boylan transformed raw, wealthy girls into perfect wives and hostesses. A bride from Boylan’s was known to be the ideal ornament to a successful man.

The gathering tonight was special, and well attended by members of the elite group informally known as the Old Settlers. As it was a Sunday, there would be no dancing ball, so it was dubbed an evangelical evening, featuring a famous preacher, the Reverend Mr. Dwight L. Moody.

Proper Catholics were supposed to turn a deaf ear to evangelists, but Kathleen had always been challenged by the notion of being proper. Besides, the lecture was nothing more than an excuse for people to get together and gossip and flirt on a Sunday night. Everyone—except perhaps the Reverend himself—knew that. It was all part of the elaborate mating ritual of the upper class, and it fascinated Kathleen. Many a night she had stayed back at the school, paging through Godey’s Lady’s Book, studying the color fashion plates and wondering what it would be like to join the rare, privileged company of the elite.

Tonight, fate or simple happenstance held out the opportunity. Miss Deborah had taken ill and had gone home to her father. As a lark, Phoebe and Lucy had decided to try what Lucy termed a “social experiment.”

Lucy swore that people were easily led and swayed by appearances, and there was no real distinction between the classes. A poor girl dressed as a princess would be as warmly received as royalty. Phoebe, on the other hand, believed that class was something a person was born with, like straight teeth or brown hair, and that people of distinction could spot an imposter every time.

Kathleen was their willing subject for the experiment. She had always been intrigued by rich people, having lived outside their charmed circle, looking in, for most of her life. At last she would join their midst, if only for a few hours.

“Are you hoping for a private moment with Mr. Kennedy?” Lucy asked Phoebe teasingly.

“He will surely be the handsomest man in attendance tonight,” Phoebe said. “But you’re welcome to him. I have a different ambition.”

“What is wrong with him?” Kathleen asked, remembering the godlike creature she had watched in the gazebo. She knew that if Phoebe had wanted Dylan Kennedy for herself, she would have had him by now. “What aren’t you telling us?”

“The fault is not with Mr. Kennedy, but with our dearest Phoebe,” Lucy said, her voice both chiding and affectionate. “She has set a standard no mortal man can possibly meet.”

“What is it that you want?” Kathleen asked.

“A duke,” Phoebe whispered, nearly swooning with the admission.

Kathleen burst out laughing. “And where do you suppose you’ll be finding one of those? Beneath a toadstool?” She feigned a mincing walk and stuck her nose in the air. “You may call me ‘your highness’ and be sure you scrape the floor when you bow.”

Lucy swallowed an outburst of laughter. “Isn’t a royal title against the law?”

“In this country,” Phoebe said with an offended sniff. “And it’s ‘Your Grace.’”

“You mean you would leave the States in your quest for a title?”

Phoebe stared at her as if she had gone daft. “I would leave the planet in order to marry a title.”

“But why?” Kathleen demanded.

“I wouldn’t expect you to understand. Honestly, you’ve never known your place, Kathleen O’Leary. Deborah spoiled you from the start.”

“That’s because Deborah is smart enough to see that divisions of class are artificial,” Lucy said. “As I intend to prove to you tonight.”

“Let’s not quarrel.” No matter how hard-pressed, Kathleen always found it easier to tolerate Phoebe’s snobbishness than to try to reason with her.

She checked inside her beaded silken reticule. As ornate as the crown jewels, the evening bag was anchored by a tasseled cord to her waist, the crystal beads catching the light each time she moved. As a lady’s maid, she knew the contents of a proper reticule: calling cards, a tiny vial of smelling salts in case she felt faint, a lace-edged handkerchief, a comb and hairpin, a coin or two.

Because she was Irish, she could not deny a superstitious streak in herself. Before leaving the school tonight, she had snatched up a talisman to carry her through the evening. It was a mass card from St. Brendan’s Church, printed in honor of her grandmother, Bridget Cavanaugh. The sturdy old woman had died three months earlier, and Kathleen ached with missing her. It seemed appropriate and oddly comforting to slip the holy card into her reticule, as if Gran were a little cardboard saint carried in her pocket. She lifted her chin and squared her shoulders. “I am as ready as a sinner on Fat Tuesday.”

She and her friends slowly approached the salon, their footfalls silent on the carpet patterned with swirling ferns. Kathleen savored every moment, every sensation, knowing that memories of this night would sustain her through all the long years to come. She tried to memorize the plush feel of the thick carpet beneath her feet, which were clad in silk slippers made to match the Worth gown. She felt the rich, heavy weight of the emerald-and-diamond collar around her neck, and the tug of the matching earrings. She listened to the polite, cultured burble of conversation in the grand salon. To her, the mingling voices sounded like a chorus of angels. Everything even smelled rich, she reflected fancifully. French perfume, Havana cigars, fine brandy, Macassar hair oil.

They reached the arched doorway flanked by tall potted plants. The breeze through an open window let in a hot gust of air, causing the ferns to nod as if in obeisance. The uncertain luster of the moon polished the spires and dome of the courthouse in the next block. Far to the west, the sky flickered and glowed with heat lightning. It was a night made for magic. Of that, Kathleen felt certain.