скачать книгу бесплатно

The trip is still a good idea, though. A long drive with no one but each other for company will give us a chance to talk about matters we’ve been avoiding all summer long, possibly her entire adolescence. When she was little, we discussed the great matters of her life at bedtime, lying together in the dark, watching the play of moon shadows on the ceiling. In high school, she stayed up later than I did, and our conversations shrank to sleepy utterances. Nighttime was punctuated by the creak of a floorboard under a furtive foot, the rasp of a toothbrush washing away the smell of a sneaked beer. Some days, we barely spoke a half-dozen words.

I want these long, empty hours with her on the road. I need them with an intensity that I hide from Molly, because I don’t want her to worry that I’m getting desperate. She’s a worrier, my Molly. A pleaser. She wants everyone to be happy, and if she had some inkling of how I’m feeling right now, she’d try to do something about it. I don’t want her to feel as if she’s responsible for my happiness. Good lord, who would wish that on a child?

We finish packing. Everything is in order, every checklist completed, our iPods organized with music and podcasts, every contact duly entered in our mobile phones. Finally, the moment has arrived.

“Well,” says Dan. “I guess that’s it.”

What’s it? I wonder. What? But I smile and say, “Yep. Ready, kiddo?”

“In a minute,” she says, stooping and patting her leg to call the dog.

I am unprepared for the wrench as she says goodbye to Hoover. We adopted the sweet-faced Lab mix as a pup when Molly was four. They grew up together—littermates, we used to call them, laughing at their rough-and-tumble antics. Since then, she has shared every important moment with the dog—holidays, neighborhood walks and summer campouts, fights with friends, Saturday morning cartoons, endless tosses of slimy tennis balls.

Through the years, Hoover has endured wearing doll clothes and sunglasses, being pushed in a stroller, taken to school for show-and-tell, and sneaked under the covers on cold winter nights. These days, he has slowed down, and is now as benign and endearing as a well-loved velveteen toy. None of us dares to acknowledge what we all know—that he will be gone by the time Molly finishes college.

She hunkers down in front of him, cradling his muzzle between her hands in the way I’ve seen her do ten thousand times before. She burrows her face into his neck and whispers something. Hoover gives a soft groan of contentment, loving the attention. When she draws away, he tries to reel her back in with a lifted front paw—Shake, boy. Molly rises slowly, grasps the paw for a moment, then gently sets it down.

Next, she turns to Dan. I notice the stiff set of his shoulders and the way he checks and rechecks everything—tires, cell phone batteries, wiper fluid. I can see him checking Molly, too, but she doesn’t recognize the pain in his probing looks. He hides behind a mask of bravado, reassuring to his daughter but transparent to me.

Their goodbye mirrors their history together through the years—loving, a little awkward. He’s never been one to show his emotions, but he was the one who taught her to swim, to laugh, to belch on command, to throw a baseball overhand, to pump up a bicycle tire, to eat smoked oysters straight out of the can, to flatten pennies on railroad tracks.

Their farewell is perfunctory, almost casual. They both seem to possess a quiet understanding that their lives are meant to intersect and diverge. “Call me tonight,” he says. “Call me whenever you want.”

“Sure, Dad. Love you.”

They hug. He kisses her on the crown of her head. His hand lingers on her arm; she doesn’t meet his eyes. Sunlight glances off the car window as she gets in.

Dan comes around to the other side and kisses me, his lips warm and familiar. “Take care, Linda,” he says in a husky voice, the same thing he always says to me, but today the words carry extra weight.

“Of course,” I say, holding him for an extra beat. Then I whisper in his ear, “How will I get through this?”

He pulls back, giving me a quizzical look. “Because you will,” he says simply. “You can do anything, Lindy.”

I smile to acknowledge the kind words, but I’m not certain I trust them.

The rearview mirror frames a view of our boxy, painted house, where we’ve lived since before Molly was born. Not for the first time, it hits me that I’ll come home to an empty nest. People say this stage of life is a golden time, filled with possibility. Someone—probably a woman with too many kids and pets—once said the true definition of freedom is when the last child leaves home and the dog dies. At last, you get your life back. Your time is your own. The trouble is—and I can’t bear to admit this, even to Dan—I never said I wanted it back.

As we pull out onto the street, he stands and watches us go, the dog leaning against his leg. My husband braces an arm on the front gate and lowers his head. When I get back from this journey, he and I will be alone again, the way we were eighteen years ago, before the explosion of love that was Molly, before late-night feedings and bouts of the croup, before scary movies and argued-over curfews, before pranks and laughter, tempests and tears.

With Molly gone, we’ll have all this extra space in our lives. I’ll have to look him in the eye and ask, “Are you still the same person I married?” Or maybe the real question is, Am I?

I picture us seated across the dinner table from each other, night after night. What will we talk about? Do we know everything about each other, or is there still more to discover? I can’t recall the last time I asked him about his dreams and desires, or the last time he asked me something more than “Did you feed the dog this morning?”

I invested so much more time in Molly over the years. When there’s a daughter keeping us preoccupied, it’s easy to slip away from each other.

With all my heart, I hope it’s equally easy to reach across the divide. I suppose I’ll find out soon enough.

Chapter Two

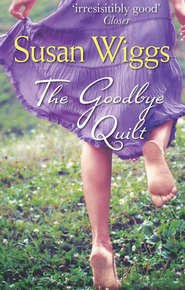

I don’t even bother offering to drive. Molly insists on driving everywhere, and has done so ever since she turned sixteen. At the moment this is a convenient arrangement. I can use the time to work on the quilt. I’m picturing the completed piece at the other end of the journey—warm and soft, a tangible reminder of Molly’s past. Each bit of fabric is a puzzle piece of her childhood, tessellating with the others around it. All that remains is to finish quilting the layers together, adding more embellishments along the way.

Working by hand rather than machine is soothing, and the pattern is free-form within the wooden hoop. On the solid pieces of fabric, words and messages can be embedded like secrets in code: Courage. You’re beautiful. Walk it off. Freud was wrong. I should declare the thing finished by now but, like a nesting magpie, I keep adding bright trinkets—a button from a favorite sweater, a blue ribbon from a piano recital, a vintage handkerchief and a paste earring that belonged to her grandmother. There’s some old, faded fabric from Molly’s kindergarten apron, green with little laughing monkey heads. And a bow from her prom corsage, worn with shining pride just a few months ago.

Though it’s impossible to be objective, I know this thing I have created is beautiful, even with all its flaws. Even though it’s not finished. This is a record of her days with me, from the moment I realized I was pregnant—I was working in the garden, wearing a yellow dotted halter top, which is now part of the quilt—to today. Yes, even today I grabbed Hoover’s favorite bandanna to incorporate.

Like so many projects I’ve tackled over the years—like parenting itself—the quilt is ambitious and unwieldy. But maybe the hours of enforced idleness in the car will be just what I need to add the final flourishes.

As we drive along the main street of our town, Molly looks out at the flower baskets on the streetlamp poles, the little coffee stands and cafés, the bank and bike shop and bookstore, the fashion boutiques and galleries advertising fall sales, the congregational church with its painted white spire. There’s the stationery shop, advertising back-to-school specials, and of course, Pins & Needles, my favorite place in town. The charming old building stands shoulder-to-shoulder between a bakery and a boutique, sharing a concrete keystone that marks the year it was built—1902. Arched windows in the upper stories, which house an optometrist and a chiropractor, are decked with wrought-iron window boxes filled with asters and mums. On the street level is the abundant display window, replete with fabrics in the delicious colors of autumn—pumpkin and amber, flame red, magenta, shadowy purple.

A small, almost apologetic-looking sign in the window says, “Business For Sale.” Minerva, the shop owner, is retiring and she’s been looking for a buyer since the previous Christmas. She’s told all her customers that if it’s not sold by the new year, she’ll simply close its doors. This option is looking more and more likely. It’s hard to imagine someone with the kind of passion and energy it takes—not to mention the capital—to run a small shop. Once the store is cleared to the bare walls, it will look like a blight on our town’s main street, a missing tooth in the middle of a smile. On top of Molly going away, it’s another blow.

Across the street is a trendy clothing boutique where Molly has spent many an hour—and many a dollar—agonizing over just the right look. As she was trying on jeans the other day, a debate ensued. Do girls on the East Coast wear skinny jeans or boot cut? Do they even wear hoodies? As if I would know these things. When she began worrying about what to wear, I realized that everything was getting very real for Molly. For a girl who has never lived anywhere else, this is a huge step. Now that we’re on the road, she is facing the reality that college is an actual place, not just a display of glossy pictures in a catalog. I want to tell her not to be afraid, but I suspect the advice wouldn’t be welcome.

Navigating the ungainly Suburban up the ramp to the interstate, Molly fiddles with the radio, but it’s all talk so she switches it off. We’ve got our iPods if we’re desperate for music.

From the grim look on Molly’s face as she cranes her neck to check the rearview mirror, it’s clear that she knows I was right about the lamp taking up too much space. I can’t help thinking what I won’t allow myself to say: I told you so.

Agitated, I put on my discount-store reading glasses—the ones that perch on my nose and make me look like a schoolmarm. Another visible rite of passage. For me, the moment occurred a few years back, when I turned thirty-nine-and-a-half. I was in a gift shop, trying to read a sale tag, and suddenly my arm wasn’t quite long enough to make out the price.

A sales clerk offered me a pair of reading glasses, and the fine print came into focus. The fact that the glasses had cute faux-Burberry frames offered scant comfort. At first, I was a bit embarrassed to put them on around Dan and Molly, but when you love needlework and crossword puzzles as much as I do, you swallow your pride.

I open the canvas quilt bag and the project spills across my lap. The oval hoop frames a section made of a calico maternity blouse I wore while carrying Molly. I stab the needle in, telling myself it’ll be finished soon enough, one stitch after another. The needle flashes in and out like a little silver dart.

“Bad intersection up here,” I say, glancing up when we reach the crossroads leading to the interstate. “Be sure you signal.”

“Hello. I’ve only been through this intersection a zillion times. And did you know that at eighteen, a person’s vision is performing at its peak?”

I adjust my glasses. “So is her smart mouth.” My needle starts writing the words “be sweet,” adding a curlicue at the end.

“I’m just saying, don’t worry about my driving. I learned from the best.”

This is true. Dan’s an excellent driver, alert and confident, traits he passed along to our daughter. Most of her friends learned through Driver’s Ed, but money was tight that year due to a layoff, and Dan did the honors. I used to wonder what they talked about during all those hours of practice, but when I asked, they both offered blank looks. “We didn’t talk about anything.”

What she means is, Dan has a way of communicating without talk. He can speak volumes with a glance, a chuckle or a shrug. The two of them are comfortable in their silence in the way Molly and I are comfortable nattering away at each other.

Sure enough, there’s a small tangle of traffic at the intersection, but I bite my tongue. Literally, I press my teeth into my tongue. I will not speak up. The time is past for correcting my daughter, giving directives. These final days together should be special, sacred almost, the last slender thread of a bond that has endured for eighteen years and is about to be willfully severed.

Molly expertly accelerates up the on-ramp and merges smoothly with the flow of traffic. She keeps her eyes on the road, her profile delicate and clean-lined, startlingly adult.

It’s a bright September morning, and the lingering heat of late summer shimmers, turning the asphalt into a river of mercury. With a flick of her little finger, Molly signals and moves into the swift current of the middle lane. She is a competent driver, skilled, even. She’s competent and skilled at many things—water polo, trigonometry, getting rid of phone solicitors, being a good friend.

Her spirit, her self-assurance and independence, are the sort of wonderful qualities a mother wants in her daughter. My goal was always to raise a child capable of making judgments on her own. Teaching her has been a joyous process, while actually seeing her go off in her own direction is intensely bittersweet. Adulthood, I suppose, is the final exam to see which lessons she absorbed.

“What do you suppose your father’s doing?” I ask, picturing Dan alone in the house. For the next several days, his diet will consist only of things that can be made from tortilla chips, cheese and cold cuts.

Molly shrugs. Her shiny dark curls spring with the motion. “He’s probably breaking out the cigars.”

I think of him standing on the driveway this morning, giving his daughter an awkward hug before stepping back, stiff-faced, his eyes shining. I wonder if she looked in the rearview mirror as we pulled away, if she saw her father bow his head, then lean down to pet the dog.

“Oh, come on,” I chide her. “Is that what you really think?”

“I don’t know. I figure he’s been looking forward to this day for a long time. Dad’s good with change.”

Meaning I’m not. And although he might be good with this particular change, there’s a part of him that has come unmoored. Dan loves Molly with both a consuming flame and a heart-pounding fear. Their complicated relationship has always been full of contradictions. Dan was in the delivery room when Molly was born on a cold February morning eighteen years ago, and the moment the baby appeared in all her pulsing, slippery, newborn glory, he wept, the tears soaking into the paper surgical mask they’d made him wear. The first time Molly was placed in his arms, he held the tiny bundle with the shocked immobility of abject terror. He hadn’t smiled down into the red, wrinkled face, not the way I did, instantly a mother, with a mother’s serene confidence and a sense of accomplishment so intense I was floating. He hadn’t cooed and swayed to that universal internal lullaby all mothers begin to hear the moment the baby is laid in their arms. He had simply stood and looked as though someone had handed him a vial of nitroglycerin.

Yet last night, I awakened to find him crying. He was absolutely silent, but the bed quivered with his fight to keep from making a sound. I said nothing, but lay perfectly still, helplessly drifting. Have I lost the ability to comfort him? Maybe I just didn’t want to intrude. We are each dealing with the departure of our only child in our own way. When you’re married, you don’t get to be let in, not to everything.

“Trust me,” I assure Molly. “He’s going to miss you like crazy.”

“He never said so.”

“He wouldn’t. But that doesn’t mean he won’t be missing you every single second.”

“I guess.”

Too often, there’s a disconnect between Dan and Molly, despite the undeniable fact that they love each other. I pause, frowning at a knot that has formed in my thread. “That’s just the way he is,” I tell Molly. This is my role—the go-between, translating for the two of them.

I tease the knot loose and go back to my stitching. The border abuts a trapezoid-shaped swatch of neutral-colored lawn, snipped from the dress she wore to the eighth-grade banquet, the first grown-up dance of her life. At age thirteen she was impossible, taking drama to new heights and sullenness to new depths. I used to try to turn our dirgelike family dinners into something a little more upbeat. “What’s the highlight of your day?” I used to ask my husband and daughter. “What’s the one thing that makes it worth getting up in the morning?”

Dan had been grinding pepper on his salad in that deliberate way of his. Barely looking up, he said, “When Molly smiles at me.”

He startled both Molly and me with that remark. And our sullen, teenage daughter had smiled at him.

Now Molly’s phone rings with a familiar tone—an Eddie Vedder song called “The Face of Love.” It’s Travis’s ringtone.

A heartbreaking softness suffuses her face as she picks up. “Hi,” she says, her voice as intimate as a lover’s. “I’m driving.” She listens for a moment, then ends with a “Yeah, me, too,” and closes the phone.

More silence. The needle darts. The day slides by the car windows. Prairie towns between endless grasslands. We make a pit stop, eat some junk food, talk about nothing. Same as we always do.

DAY TWO

Odometer Reading 121,633

… it may have been some unconsciously

craved compensation for the drab

monotony of their days that caused the

women … to evolve quilt patterns

so intricate. Only a soul in desperate

need of nervous outlet could have

conceived and executed, for instance,

the “Full Blown Tulip” …

—Ruth E. Finley,

Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them

Chapter Three

“Remember this one?” I ask, angling part of the quilt into Molly’s line of vision.

“I guess.”

“I bet you don’t remember it.”

“Then why did you ask? You always do that, Mom.”

“Do I? I never noticed.”

“You’re always quizzing me about stuff you think should be important to me.”

“Really? Yikes.” I brush my hand over the piece of purple cotton, covered by lace.

“So what about that one?” She is instantly suspicious. All summer long, little “do-you-remembers” and “last times” have sneaked in—the last time we drove to the lake at the county line to set off fireworks, the last time Dan and I attended one of her piano recitals, the last time she went for a haircut at the Twirl & Curl.

“It’s from a dress your father bought you,” I say, needle pushing in and out, running a line of stitches to spell out Daddy’s girl.

“Dad bought me a dress? No way.”

“He did, at the Mexican Marketplace. I can’t believe you forgot.”

“Mom. What was I, three or four years old?”

“Four, I think.”

“I rest my case.”

In my mind’s eye, I can still see her turning in front of the hall mirror, showing off the absurd confection of purple cotton and cheap lace. “It swirls,” Molly had shouted, spinning madly. “It swirls!” I was less charmed when she insisted on wearing it to church for the next nine weeks. The dress fell apart years ago, but there was enough fabric left to work into the quilt.

Memories flow past in a swift smear of color, like the warehouses and billboards lining the interstate. When I shut my eyes, I can picture so many moments, frozen in time. So many details, sharp as a captured image—the wisp of my newborn baby’s hair, the sweet curve of her cheek as she nurses. I can still imagine the drape of her christening gown, which is wrapped in tissue now, stored in the bottom of the painted cedar chest in the guestroom. I can clearly see myself poking a spoonful of white cereal into a round little birdlike mouth. I see Molly spring forward on chubby legs off the side of the pool, into my outstretched arms.

All those firsts. The first day of kindergarten: Molly wore her hair in two tight pigtails, her plaid jumper ironed in crisp pleats, her backpack filled with waxy-smelling new crayons, sharpened pencils, lined paper, a lunch I’d spent forty-five minutes preparing.

“Do you remember your first day of school?” I ask her now, flourishing the part of the quilt made of the uniform blouse.

“Sure. My teacher was Miss Robinson, and I carried a Mulan lunch box.” Molly changes lanes and eases past a poky hybrid car. “You put a note in my lunch. I always liked it when you did that.”

I don’t recall the teacher or the lunch box, but I definitely remember the note, the first of many I would tuck into Molly’s lunch over the years. I always tried to write a few words on a paper napkin with a little smiling cartoon mommy, with squiggles to represent my hair, and the message “I LOVE.png U. Love, Mommy.”

I tried to upgrade my wardrobe for the occasion, wearing slacks, Weejuns and coral lip gloss from a department store counter. I felt important, compelled by mission and duty, as Molly chattered gleefully in the back of my station wagon.

Stopping at the tree-shaded curb of the school, I pretended to be calm and cheerful as I kissed Molly’s cheek, stroked her head and then smilingly waved goodbye. She met up with her friends Amber and Rani. The girls went inside together, giggling and skipping the whole way, into the redbrick institution that suddenly looked huge and forbidding to me.