скачать книгу бесплатно

After the smoke had finally cleared and a desultory, unreliable rain shower had spat out the last of the embers, Lucy, her mother and a fretful baby had gathered around a table with the bankers and lawyers, to learn that the Colonel had left them destitute. The fire had not only taken the Colonel, but his fortune as well, which had been invested in a Hersholt’s Brewery and Liquor Warehouse. Uninsured, it had burned to the ground that hot, windy October night.

Her mother was lost without her beloved Colonel. As much as Lucy had loved her father and grieved for him, she’d also raged at him. His love for her and her mother had been as crippling as leg irons. He had willfully and deliberately kept them ignorant of finance, believing they were better off not knowing the precarious state of the family fortune. His smothering shield had walled them off from the truth.

For days after the devastating news had been delivered, Lucy and her mother, burdened with a demanding little stranger, had sat frozen in a state of dull shock while the estate liquidators had carted off the antiques, the furniture, the art treasures. Lucy and her mother had been forced to sell the house, their jewels, their good clothing—everything down to the last salt cellar had to go. By the time the estate managers and creditors had finished, they had nothing but the clothes on their backs and a box of tin utensils. Viola had taken ill; to this day Lucy was convinced that humiliation was more of a pestilence to her than the typhoid.

There was nothing quite so devastating as feeling helpless, she discovered. Like three bobbing corks in an endless sea, she and her mother and the baby had drifted from day to day.

Lucy had found temporary relief quarters in a shantytown by the river. She would have prevailed upon friends, but Viola claimed the shame was more than she could bear, so they huddled alone around a rusty stove and tried to bring their lives into some sort of order. Not an easy task when all Viola knew in the world was the pampering and sheltering of her strong, controlling husband; all Lucy knew was political rhetoric.

It was providence, Lucy always thought, that she’d been poking through rubbish for paper to start a fire, and had come across a copy of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, published by Tennessee Claflin and her sister, Victoria Woodhull, known in those days as The Firebrand of Wall Street. Since she’d appeared before Congress and run for president the year of the Great Fire, the flamboyant crusader had captivated Lucy’s imagination and inflamed her sense of righteousness. But that cold winter day, while huddled over a miserable fire, Lucy had read the words that had changed the course of her life. A woman’s ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and brutality of men than her ability to vote.

Suddenly Lucy knew what she must do—something she believed in with all her heart, something she’d loved since she was a tiny child.

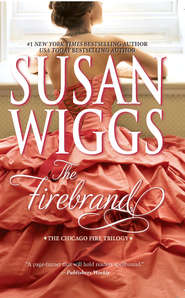

Everything had fallen into place after that epiphany. In the fast-recovering city, Lucy had taken a bank loan, leased a shop in Gantry Street, occupied the small apartment above it and hung out her tradesman’s shingle: The Firebrand—L. Hathaway, Bookseller.

Running a bookshop hadn’t made her a wealthy woman, not in the financial sense, anyway. But the independence it afforded, and the knowledge that she purveyed books that made a difference in people’s lives, brought her more fulfillment than a railroad fortune.

The trouble was, one could not dine upon spiritual satisfaction. One could not clothe one’s fast-growing daughter with moral righteousness. Not during a Chicago winter, anyway.

Silky, the calico cat they had adopted a few years back, slunk into the room, sniffing the air in queenly fashion. Maggie jumped down from Lucy’s lap and stroked the cat, which showed great tolerance for the little girl’s zealous attentions.

“Run along, then,” she said, kissing the top of Maggie’s head. “Tell Grammy Vi that I’ve gone down to the shop.”

“And bicycles later,” Maggie reminded her.

“Bicycles later,” said Lucy.

Tucking the paper under her arm, she took the back stairs down to the tiny courtyard behind the shop. A low concrete wall surrounded an anemic patch of grass. A single crabapple tree grew from the center, and just this year it had grown stout enough to support a rope swing for Maggie. The tiny garden bore no resemblance to the lush expanses of lawn that had surrounded the mansion where Lucy had grown up, but the shop was just across the way from Lloyd Park, where white-capped nannies and black-gowned governesses brought their charges to play each day. When the weather was fine, Maggie spent hours there, racing around, heedless of the censorious glares of the governesses who were clearly scandalized by hoydenish behavior.

Lucy allowed herself a wicked smile as she thought of this. She was raising Maggie to be free and unfettered. No corsets and stays for her daughter. No eye-pulling braids or heat-induced ringlets. Maggie wore loose Turkish-style trousers, her hair cropped short and an exuberant grin on her face.

But sometimes, when she wondered about where she’d come from, she asked hard questions.

Lucy took a deep breath, squared her shoulders and walked into the shop. The bell over the door chimed, drawing the attention of Willa Jean.

“Good morning,” Lucy said cheerfully. No matter what her troubles, the very sensation of being in the middle of the bookstore, her bookstore, lifted her heart. There was something about books. The smell of leather and ink. The neat, solid rows of volumes, carefully catalogued spine-out on the shelves. The lemony scent of furniture oil on the tables and the friendly creak of the pine plank floor. The gentle hiss of gaslight, the scratching of Willa Jean’s pencil. Most of all, Lucy supposed, she loved the sense that she stood in the middle of something she’d built, all on her own. She’d spun it out of a dream, dug it out of disaster and lavished her love upon it the way many women did when building a home.

This was her home. And if, from time to time, she felt an ache of loneliness that not even Maggie could fill, she still told herself she had more than most women could expect in a lifetime, and she should be grateful. Those secret yearnings shamed her. She was supposed to be a New Woman, fulfilled by her own industry.

The one thing she couldn’t figure out was how a New Woman dealt with needs as old as time. In certain quiet moments, the old loneliness stole over her. With veiled envy she watched young couples strolling together or stealing kisses when they thought no one was watching. Too often, she caught herself yearning to know a man’s touch, his affectionate regard and his passion. The one drawback to free love, she’d discovered, was that with so many choices available, no man seemed likely to choose her.

“’Bout time you got yourself down here.” Willa Jean peered accusingly from beneath the green bill of her bookkeeper’s cap. “We got to go over the figures for the bank.”

A cold clutch of apprehension took hold of Lucy’s gut. She’d had the entire weekend to prepare for this, but in fact she’d tried not to think about it. Perhaps that was a bit of her mother coming out in her. If she didn’t think about troubles then they didn’t exist.

But here was a problem she couldn’t wish away.

“All right,” she said. “Show me the books, and tell me exactly what I should say to the bank.”

Willa Jean flopped open a tall ledger on the desk in front of her. Willa Jean was as clever with numbers as her sister Patience was with scripture. Willa Jean was gruff, blunt and usually right.

This morning, her bluntness was particularly apparent. “If you don’t get an extension on your loan, you’ll default and lose the shop,” she concluded.

Lucy pushed her hand against her chest, trying to still the wing beats of panic there. “I don’t expect the bank to cooperate. Our loan was sold to the Union Trust three months ago.”

“All banks are the same, girl. They want to make money off you. Your job is to prove you’re a good risk.”

“Am I a good risk, Willa Jean?”

A bark of laughter escaped the older woman. “A bookseller? Honey, it ain’t like you’re selling grain futures here.” She gestured around the shop. “These are books, see? People don’t eat them, they don’t manufacture furniture out of them, they don’t keep them to increase in value. They read them. And who has time to read? Everyone’s so all-fired busy trying to make a living, they don’t read anymore.”

“So my job is to convince a strange man that I can make a profit in a dying enterprise.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Remind me. Why did I get up this morning?”

Willa Jean held out an appointment card. “There’s the name of the person you’re to see. It’s the bank president, girl. At least that’s something.”

Lucy glanced at the card, then froze in amazement. She was looking at a name she hadn’t seen in a very long time, but one she had never forgotten. Mr. Randolph B. Higgins.

Chapter Seven

“Mr. Higgins?”

Rand glanced up from his desk to see his secretary in the doorway to the office. “Yes, Mr. Crowe?”

The earnest young man crossed the room and held out a small note. “A message from Mrs. Higgins, sir.”

“Thank you, Mr. Crowe. Do I have any other appointments this afternoon?”

“One more, sir. It’s about a loan extension.” He set down a flat cardstock file, bound with a brown satin ribbon. “One of those loans in the batch you acquired from Commonwealth Securities.”

“Thank you,” Rand said again, keeping his expression impassive. He never betrayed his opinion about a professional matter, even to his secretary. It was this fierce discretion that had secured his reputation in the banking business, and he wasn’t about to compromise that.

In the years since the fire, Rand had discovered within himself not just a talent for banking, but a passion for it. He welcomed the responsibility of looking after people’s money and embraced the task of lending to those who demonstrated a brilliant idea, an acute need or a promising enterprise. Sometimes he thought his love of banking was the only reason he’d carried on following those shadowy, pain-filled months after the fire.

When Crowe left, Rand opened the note, written in a fine, spiderweb hand on cream stock imported from England. At the top was the Higgins crest, a pretentious little vanity created by his great-grandfather decades ago. The gold embossed emblem of an eagle winked in the strong sunlight of late afternoon. Rand stood by the window to read the note.

Another invitation, of course. She was constantly trying to broaden his social horizons, trolling the elite gatherings of the city like fishermen trolled Lake Michigan for pike, and setting her netted catch before Rand.

The trouble was, he thought wryly, that after a while the catch began to stink. It wasn’t that he had no interest in social advancement—he knew as well as anyone that, in his business, connections mattered. It was just that he found them tedious and, deep down, hurtful.

This evening’s soiree was a reception for a popular politician, arranged by Jasper Lamott, who also happened to be on the board of the Union Trust. Lamott’s group, a conservative organization called the Brethren of Orderly Righteousness, was raising funds to oppose a bill before the legislature giving women dangerously broad rights to file suit against their own husbands. Like all decent men, Rand was alarmed by the rapid spread of the women’s suffrage movement, which was causing families to break apart all across the country. He believed women were best suited to their place as keepers of hearth and home, with men serving as providers and protectors. Perhaps he would attend the event after all. He would most certainly make a generous donation to the cause. The fact that women no longer knew or respected their place had brought him no end of trouble, and he supported those who labored to correct the situation for society in general.

Taking advantage of a rare lull in the day’s activities, he turned to the picture window, with its leaded fanlights. Resting his hands on the cool marble windowsill, he looked out.

It was a dazzling spring afternoon, the sunlight shimmering across the lake and illuminating the neatly laid-out streets of the business district. Across from the bank was a park surrounded by a handsome wrought-iron fence. In the center, a larger-than-life statue of Colonel Hiram B. Hathaway commemorated his heroism in the War Between the States. Slender poplar and maple trees lined the walkways. The green of the grass was particularly intense. Newcomers to town often commented on the deep emerald shade of the grass in the rebuilt city. Some theorized that the Great Fire of ‘71 left the soil highly fertile, so that all the new growth was surpassingly healthy.

Rand looked down at his scarred hands and felt the ache of the old unhealed injury in his shoulder.

He started to turn away from the window to neaten his desk for the next appointment when he spied something that made him pivot back and stare. Out in the street, wobbling along like a pair of circus performers, were two bicyclists. It was a common enough sight of late. Bicycles were all the rage, and recent improvements in the design had made the new models slightly less hazardous than the extreme high-wheelers. In the lead rode a black-haired woman, followed by a scruffy little boy on a child-size bicycle of his own.

They looked absurd, yet he couldn’t take his gaze away. Patently absurd. The woman’s dress was all rucked up in the middle, bloomers bared to the knees for anyone to see. The boy resembled a beggar in patched knickers and a flat cap set askew atop his curly brown hair.

Yet even so, the sight of the child struck Rand in the only soft spot left inside him. The only place the fire hadn’t burned to hard, numb scar tissue. The lad looked to be about the age Christine would have been, had she lived.

Briefly Rand shut his eyes, but the memories pursued him as they always did. The images from the past were inside him, and he could never shut them out. He was filled with bitter regrets, and they had made him a bitter man, the sort who resented the sight of a healthy young boy and an audacious woman riding bicycles.

Each morning when he woke up, he played a cruel and terrible game with himself. He imagined how old Christine would be. He imagined the little frock she would wear, and how the morning sunlight would look shining down on her bright curls. He imagined having breakfast with her; she would probably still favor graham gems with cream. And each day, before he left for the office, he would imagine the sweetness of his daughter’s kiss upon his cheek.

Then he would force himself to open his eyes and face the harsh truth.

He opened his eyes now and studied the only picture he kept in his office. Gilt cherubs framed a photograph of Christine at fourteen months of age, clutching a favorite blanket in her left hand, startled by whatever antics the photographer had performed to get her attention. As soon as the flash had gone off in the pan, Rand recalled, she’d burst into tears of fright, but the picture showed the child who had brought him the ultimate joy with the simple fact of her existence.

He pulled in an unsteady breath. There were some moments when it was hard to resist wishing he’d lingered longer with his daughter each morning, watching the play of sunlight in her wispy curls.

He glared at the outrageous woman on the bicycle, resenting her for having the one thing he could never get back.

She wobbled to a halt in front of the bank building and dismounted gracelessly, launching herself off the bicycle like a cowboy being bucked from a horse. The lad was more nimble, landing on both feet with catlike lightness.

They leaned their bicycles against the brass-headed hitch post the bank had installed for the convenience of well-heeled customers. Then the black-haired woman shook out her skirts, straightened her ridiculous hat and marched up the marble steps to the bank. Her son came, too, clinging to her gloved hand.

Rand noticed something vaguely familiar about the woman. A chill of apprehension sped through him, and something made him pick up the file his secretary had delivered, containing the papers pertinent to his next appointment. He untied the brown satin ribbon and flipped open the file.

His next appointment was with someone he hadn’t thought about in years, but whom he’d never quite forgotten: Lucy Hathaway.

What the devil was she doing, applying to him for a loan extension?

What the hell did she need a loan for, anyway?

And what was her name now that she was a wife and mother?

Some days, he thought, scowling down at Lucy Hathaway’s file, banking offered unexpected challenges.

He stood behind his desk and waited for Crowe to show her in. She arrived like a small tempest, wrinkled skirts swinging, the feather on her hat bobbing over her brow and the little boy in tow. The lad stared openly at him, then whispered, “He’s a giant, Mama, just like—”

“Hush,” she said quickly. But her manner was all business as she held out her hand. “Mr. Higgins, how do you do?”

Oh, he remembered that husky, cultured voice from their first meeting that long-ago evening. He remembered that direct, dark-eyed stare, that challenging set to her chin. He remembered how provocative he had found her, how intrigued he’d been by her unconventional ways.

He remembered that she’d asked him to be her lover. And he remembered the look on her face when she learned he was married.

As he offered her a chair, he knew he would not have to worry about her being attracted to him now, scarred and dour creature that he had become. She gave his imperfect face, camouflaged with a mustache these days, a polite but cursory glance, nothing more.

“Very well, thank you,” he said, then glanced pointedly at the boy, who boldly peered around the plain leather-and-wood office, looking like mischief waiting to happen. “And this is…?”

“My daughter, Margaret,” said Lucy.

Margaret stuck out a grubby hand. “How do you do? My friends call me Maggie.”

Rand was thoroughly confused now. She called her son Margaret? Then it struck him—the child in the rough knickers, short hair and flat bicycle cap was a little girl. He tried not to look too startled. “I’m very pleased to meet you, Maggie.”

“I’m afraid I had no choice but to bring her along,” Lucy said. “Ordinarily there’s someone to look after her when I have meetings.”

“But today is Grammy Vi’s dominoes day,” Maggie said.

She really was a rather pretty child beneath the bad haircut and shapeless clothing. He tried to picture her in a little pinafore done up in ribbons and bows, but she moved too fast for him to form a picture. She darted around the office, spinning the globe and lifting a paperweight so that a breeze from the open side window swept a sheaf of papers to the floor.

“Maggie, don’t touch anything,” Lucy said half a second too late.

“No harm done.” Rand bent to retrieve the papers. At the same time, the little girl squatted down to help. Their hands touched, and she caught at his, rubbing her small thumb over the shiny scar tissue there.

“Did you hurt yourself?” she asked, her face as open as a flower.

“Maggie—”

“It’s all right,” Rand said with rare patience. He was accustomed to people staring, and to youngsters who didn’t know any better asking questions. Some children turned away in fright, but not this one. She regarded him with a matter-of-fact compassion that comforted rather than discomfited. He studied her small, perfect hand covering his large, damaged one. “I did hurt myself,” he said, “a long time ago.”

“Oh.” She handed him the rest of the papers. “Does it still hurt?”

Every day.

He straightened up, put the papers back under the paperweight, then saw Crowe standing in the doorway.

“Is everything all right, sir?” Crowe asked.

“Everything’s fine,” Rand said.

“I wondered if the little b—”

“Miss Maggie would love to join you in the outer office,” Rand said hastily, cutting him off. He winked at Maggie. “Mr. Crowe is known to keep a supply of peppermints in his desk, for special visitors.”

“Can I, Mama?” Maggie’s eyes sparkled like blue flames, and suddenly she didn’t look at all like a boy.

“Run along,” Lucy said. “Don’t get into anything.”

After the door closed, Rand said, “Congratulations. You have a very lively little girl.”

“Thank you.”

“You and your husband must be very proud of her.”

“I’m afraid Maggie’s father is deceased,” she said soberly.

His heart lurched. “I’m terribly sorry.”

“Thank you, but I never knew the man,” she replied. Then she laughed at his astonished expression. “Forgive me, Mr. Higgins. I’m doing a poor job explaining myself. Maggie is my adopted daughter. She was orphaned in the fire of ‘71.”