Полная версия:

Journey to the Centre of the Earth

JOURNEY TO THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH

Jules Verne

Contents

Cover

Title Page

CHAPTER 1: The Professor and His Family

CHAPTER 2: A Mystery to be Solved at any Price

CHAPTER 3: The Runic Writing Exercises the Professor

CHAPTER 4: The Enemy to be Starved into Submission

CHAPTER 5: Famine, then Victory, Followed by Dismay

CHAPTER 6: Exciting Discussions about an Unparalleled Enterprise

CHAPTER 7: A Woman’s Courage

CHAPTER 8: Serious Preparations for Vertical Descent

CHAPTER 9: Iceland! but what Next?

CHAPTER 10: Interesting Conversations with Icelandic Savants

CHAPTER 11: A Guide Found to the Centre of the Earth

CHAPTER 12: A Barren Land

CHAPTER 13: Hospitality Under the Arctic Circle

CHAPTER 14: But Arctics can be Inhospitable, too

CHAPTER 15: SnÆfell at Last

CHAPTER 16: Boldly Down the Crater

CHAPTER 17: Vertical Descent

CHAPTER 18: The Wonders of Terrestrial Depths

CHAPTER 19: Geological Studies in Situ

CHAPTER 20: The First Signs of Distress

CHAPTER 21: Compassion Fuses the Professor’s Heart

CHAPTER 22: Total Failure of Water

CHAPTER 23: Water Discovered

CHAPTER 24: Well Said, Old Mole! Canst Thou Work I’ the Ground so Fast?

CHAPTER 25: De Profundis

CHAPTER 26: The Worst Peril of All

CHAPTER 27: Lost in the Bowels of the Earth

CHAPTER 28: The Rescue in the Whispering Gallery

CHAPTER 29: Thalatta! Thalatta!

CHAPTER 30: A New Mare Internum

CHAPTER 31: Preparations for a Voyage of Discovery

CHAPTER 32: Wonders of the Deep

CHAPTER 33: A Battle of Monsters

CHAPTER 34: The Great Geyser

CHAPTER 35: An Electric Storm

CHAPTER 36: Calm Philosophic Discussions

CHAPTER 37: The Liedenbrock Museum of Geology

CHAPTER 38: The Professor in His Chair Again

CHAPTER 39: Forest Scenery Illuminated by Electricity

CHAPTER 40: Preparations for Blasting a Passage to the Centre of the Earth

CHAPTER 41: The Great Explosion and the Rush Down Below

CHAPTER 42: Headlong Speed Upward Through the Horrors of Darkness

CHAPTER 43: Shot Out of a Volcano at Last!

CHAPTER 44: Sunny Lands in the Blue Mediterranean

CHAPTER 45: All’s Well that Ends Well

CLASSIC LITERATURE: WORDS AND PHRASES adapted from the Collins English Dictionary

About the Author

History of Collins

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 The Professor and His Family

On the 24th of May, 1863, my uncle, Professor Liedenbrock, rushed into his little house, No. 19 Königstrasse, one of the oldest streets in the oldest portion of the city of Hamburg.

Martha must have concluded that she was very much behindhand, for the dinner had only just been put into the oven.

“Well, now,” said I to myself, “if that most impatient of men is hungry, what a disturbance he will make!”

“M. Liedenbrock so soon!” cried poor Martha in great alarm, half opening the dining-room door.

“Yes, Martha; but very likely the dinner is not half cooked, for it is not two yet. Saint Michael’s clock has only just struck half-past one.”

“Then why has the master come home so soon?”

“Perhaps he will tell us that himself.”

“Here he is, Monsieur Axel; I will run and hide myself while you argue with him.”

And Martha retreated in safety into her own dominions.

I was left alone. But how was it possible for a man of my undecided turn of mind to argue successfully with so irascible a person as the Professor? With this persuasion I was hurrying away to my own little retreat upstairs, when the street door creaked upon its hinges; heavy feet made the whole flight of stairs shake; and the master of the house, passing rapidly through the dining-room, threw himself in haste into his own sanctum.

But on his rapid way he had found time to fling his hazel stick into a corner, his rough broadbrim upon the table, and these few emphatic words at his nephew:

“Axel, follow me!”

I had scarcely had time to move when the Professor was again shouting after me:

“What! not come yet?”

And I rushed into my redoubtable master’s study.

Otto Liedenbrock had no mischief in him, I willingly allow that; but unless he very considerably changes as he grows older, at the end he will be a most original character.

He was professor at the Johannæum, and was delivering a series of lectures on mineralogy, in the course of every one of which he broke into a passion once or twice at least. Not at all that he was over-anxious about the improvement of his class, or about the degree of attention with which they listened to him, or the success which might eventually crown his labours. Such little matters of detail never troubled him much. His teaching was, as the German philosophy calls it, “subjective”; it was to benefit himself, not others. He was a learned egotist. He was a well of science, and the pulleys worked uneasily when you wanted to draw anything out of it. In a word, he was a learned miser.

Germany has not a few professors of this sort.

To his misfortune, my uncle was not gifted with a sufficiently rapid utterance; not, to be sure, when he was talking at home, but certainly in his public delivery; this is a want much to be deplored in a speaker. The fact is, that during the course of his lectures at the Johannæum, the Professor often came to a complete standstill; he fought with wilful words that refused to pass his struggling lips, such words as resist and distend the cheeks, and at last break out into the unasked-for shape of a round and most unscientific oath: then his fury would gradually abate.

Now in mineralogy there are many half-Greek and half-Latin terms, very hard to articulate, and which would be most trying to a poet’s measures. I don’t wish to say a word against so respectable a science, far be that from me. True, in the august presence of rhombohedral crystals, retinasphaltic resins, gehlenites, Fassaites, molybdenites, tungstates of manganese, and titanite of zirconium, why, the most facile of tongues may make a slip now and then.

It therefore happened that this venial fault of my uncle’s came to be pretty well understood in time, and an unfair advantage was taken of it; the students laid wait for him in dangerous places, and when he began to stumble, loud was the laughter, which is not in good taste, not even in Germans. And if there was always a full audience to honour the Liedenbrock courses, I should be sorry to conjecture how many came to make merry at my uncle’s expense.

Nevertheless my good uncle was a man of deep learning—a fact I am most anxious to assert and reassert. Sometimes he might irretrievably injure a specimen by his too great ardour in handling it; but still he united the genius of a true geologist with the keen eye of the mineralogist. Armed with his hammer, his steel pointer, his magnetic needles, his blowpipe, and his bottle of nitric acid, he was a powerful man of science. He would refer any mineral to its proper place among the six hundred* elementary substances now enumerated, by its fracture, its appearance, its hardness, its fusibility, its sonorousness, its smell, and its taste.

The name of Liedenbrock was honourably mentioned in colleges and learned societies. Humphry Davy,† Humboldt, Captain Sir John Franklin, General Sabine, never failed to call upon him on their way through Hamburg. Becquerel, Ebelman, Brewster, Dumas, Milne-Edwards, Saint-Claire-Deville frequently consulted him upon the most difficult problems in chemistry, a science which was indebted to him for considerable discoveries, for in 1853 there had appeared at Leipzig an imposing folio by Otto Liedenbrock, entitled, “A Treatise upon Transcendental Chemistry,” with plates; a work, however, which failed to cover its expenses.

To all these titles to honour let me add that my uncle was the curator of the museum of mineralogy formed by M. Struve, the Russian ambassador; a most valuable collection, the fame of which is European.

Such was the gentleman who addressed me in that impetuous manner. Fancy a tall, spare man, of an iron constitution, and with a fair complexion which took off a good ten years from the fifty he must own to. His restless eyes were in incessant motion behind his full-sized spectacles. His long, thin nose was like a knife blade. Boys have been heard to remark that that organ was magnetised and attracted iron filings. But this was merely a mischievous report; it had no attraction except for snuff, which it seemed to draw to itself in great quantities.

When I have added, to complete my portrait, that my uncle walked by mathematical strides of a yard and a half, and that in walking he kept his fists firmly closed, a sure sign of an irritable temperament, I think I shall have said enough to disenchant any one who should by mistake have coveted much of his company.

He lived in his own little house in Königstrasse, a structure half brick and half wood, with a gable cut into steps; it looked upon one of those winding canals which intersect each other in the middle of the ancient quarter of Hamburg, and which the great fire of 1842 had fortunately spared.

It is true that the old house stood slightly off the perpendicular, and bulged out a little towards the street; its roof sloped a little to one side, like the cap over the left ear of a Tugendbund student; its lines wanted accuracy; but after all, it stood firm, thanks to an old elm which buttressed it in front, and which often in spring sent its young sprays through the window panes.

My uncle was tolerably well off for a German professor. The house was his own, and everything in it. The living contents were his god-daughter Gräuben, a young Virlandaise of seventeen, Martha, and myself. As his nephew and an orphan, I became his laboratory assistant.

I freely confess that I was exceedingly fond of geology and all its kindred sciences; the blood of a mineralogist was in my veins, and in the midst of my specimens I was always happy.

In a word, a man might live happily enough in the little old house in the Königstrasse, in spite of the restless impatience of its master, for although he was a little too excitable—he was very fond of me. But the man had no notion how to wait; nature herself was too slow for him. In April, after he had planted in the terra-cotta pots outside his window seedling plants of mignonette and convolvulus, he would go every evening and give them a little pull by their leaves to make them grow faster. In dealing with such a strange individual there was nothing for it but prompt obedience. I therefore rushed after him.

*Sixty-three. (Tr.)

†As Sir Humphry Davy died in 1829, the translator must be pardoned for pointing out here an anachronism, unless we are to assume that the learned Professor’s celebrity dawned in his earliest fears. (Tr.)

CHAPTER 2 A Mystery to be Solved at any Price

That study of his was a museum, and nothing else. Specimens of everything known in mineralogy lay there in their places in perfect order, and correctly named, divided into inflammable, metallic, and lithoid minerals.

How well I knew all these bits of science! Many a time, instead of enjoying the company of lads of my own age, I had preferred dusting these graphites, anthracites, coals, lignites, and peats! And there were bitumens, resins, organic salts, to be protected from the least grain of dust; and metals, from iron to gold; metals whose current value altogether disappeared in the presence of the republican equality of scientific specimens; and stones too, enough to rebuild entirely the house in Königstrasse, even with a handsome additional room, which would have suited me admirably.

But on entering this study now I thought of none of all these wonders; my uncle alone filled my thoughts. He had thrown himself into a velvet easy-chair, and was grasping between his hands a book over which he bent, pondering with intense admiration.

“Here’s a remarkable book! What a wonderful book!” he was exclaiming.

These ejaculations brought to my mind the fact that my uncle was liable to occasional fits of bibliomania; but no old book had any value in his eyes unless it had the virtue of being nowhere else to be found, or, at any rate, of being illegible.

“Well, now; don’t you see it yet? Why I have got a priceless treasure, that I found this morning, in rummaging in old Hevelius’s shop, the Jew.”

“Magnificent!” I replied, with a good imitation of enthusiasm.

What was the good of all this fuss about an old quarto, bound in rough calf, a yellow faded volume, with a ragged seal depending from it?

But for all that there was no lull yet in the admiring exclamations of the Professor.

“See,” he went on, both asking the questions and supplying the answers. “Isn’t it a beauty? Yes; splendid! Did you ever see such a binding? Doesn’t the book open easily? Yes; it stops open anywhere. But does it shut equally well? Yes; for the binding and the leaves are flush, all in a straight line, and no gaps or openings anywhere. And look at its back, after seven hundred years. Why, Bozerian, Closs, or Purgold might have been proud of such a binding!”

While rapidly making these comments my uncle kept opening and shutting the old tome. I really could do no less than ask a question about its contents, although I did not feel the slightest interest.

“And what is the title of this marvellous work?” I asked with an affected eagerness which he must have been very blind not to see through.

“This work,” replied my uncle, firing up with renewed enthusiasm, “this work is the Heims Kringla of Snorre Turlleson, the most famous Icelandic author of the twelfth century! It is the chronicle of the Norwegian princes who ruled in Iceland.”

“Indeed;” I cried, keeping up wonderfully, “of course it is a German translation?”

“What!” sharply replied the Professor, “a translation! What should I do with a translation? This is the Icelandic original, in the magnificent idiomatic vernacular, which is both rich and simple, and admits of an infinite variety of grammatical combinations and verbal modifications.”

“Like German,” I happily ventured.

“Yes,” replied my uncle, shrugging his shoulders; “but, in addition to all this, the Icelandic has three numbers like the Greek, and irregular declensions of nouns proper like the Latin.”

“Ah!” said I, a little moved out of my indifference; “and is the type good?”

“Type! What do you mean by talking of type, wretched Axel? Type! Do you take it for a printed book, you ignorant fool? It is a manuscript, a Runic manuscript.”

“Runic?”

“Yes. Do you want me to explain what that is?”

“Of course not,” I replied in the tone of an injured man. But my uncle persevered, and told me, against my will, of many things I cared nothing about.

“Runic characters were in use in Iceland in former ages. They were invented, it is said, by Odin himself. Look there, and wonder, impious young man, and admire these letters, the invention of the Scandinavian god!”

Well, well! not knowing what to say, I was going to prostrate myself before this wonderful book, a way of answering equally pleasing to gods and kings, and which has the advantage of never giving them any embarrassment, when a little incident happened to divert the conversation into another channel.

This was the appearance of a dirty slip of parchment, which slipped out of the volume and fell upon the floor.

My uncle pounced upon this shred with incredible avidity. An old document, enclosed an immemorial time within the folds of this old book, had for him an immeasurable value.

“What’s this?” he cried.

And he laid out upon the table a piece of parchment, five inches by three, and along which were traced certain mysterious characters.

Here is the exact facsimile. I think it important to let these strange signs be publicly known, for they were the means of drawing on Professor Liedenbrock and his nephew to undertake the most wonderful expedition of the nineteenth century.

The Professor mused a few moments over this series of characters; then raising his spectacles he pronounced:

“These are Runic letters; they are exactly like those of the manuscript of Snorre Turlleson. But, what on earth is their meaning?”

Runic letters appearing to my mind to be an invention of the learned to mystify this poor world, I was not sorry to see my uncle suffering the pangs of mystification. At least, so it seemed to me, judging from his fingers, which were beginning to work with terrible energy.

“It is certainly old Icelandic,” he muttered between his teeth.

And Professor Liedenbrock must have known, for he was acknowledged to be quite a polyglott. Not that he could speak fluently in the two thousand languages and twelve thousand dialects which are spoken on the earth, but he knew at least his share of them.

So he was going, in the presence of this difficulty, to give way to all the impetuosity of his character, and I was preparing for a violent outbreak, when two o’clock struck by the little timepiece over the fireplace.

At that moment our good housekeeper Martha opened the study door, saying:

“Dinner is ready!”

I am afraid he sent that soup to where it would boil away to nothing, and Martha took to her heels for safety. I followed her, and hardly knowing how I got there I found myself seated in my usual place.

I waited a few minutes. No Professor came. Never within my remembrance had he missed the important ceremonial of dinner. And yet what a good dinner it was! There was parsley soup, an omelette of ham garnished with spiced sorrel, a fillet of veal with compóte of prunes; for dessert, crystallised fruit; the whole washed down with sweet Moselle.

All this my uncle was going to sacrifice to a bit of old parchment. As an affectionate and attentive nephew I considered it my duty to eat for him as well as for myself, which I did conscientiously.

“I have never known such a thing,” said Martha. “M. Liedenbrock is not at table!”

“Who could have believed it?” I said, with my mouth full.

“Something serious is going to happen,” said the old servant, shaking her head.

My opinion was, that nothing more serious would happen than an awful scene when my uncle should have discovered that his dinner was devoured. I had come to the last of the fruit when a very loud voice tore me away from the pleasures of my dessert. With one spring I bounded out of the dining room into the study.

CHAPTER 3 The Runic Writing Exercises the Professor

“Undoubtedly it is Runic,” said the Professor, bending his brows; “but there is a secret in it, and I mean to discover the key.”

A violent gesture finished the sentence.

“Sit there,” he added, holding out his fist towards the table. “Sit there, and write.”

I was seated in a trice.

“Now I will dictate to you every letter of our alphabet which corresponds with each of these Icelandic characters. We will see what that will give us. But, by St. Michael, if you should dare to deceive me—”

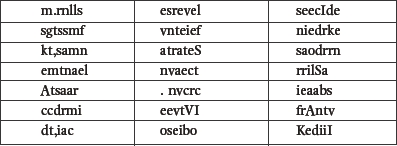

The dictation commenced. I did my best. Every letter was given me one after the other, with the following remarkable result:

When this work was ended my uncle tore the paper from me and examined it attentively for a long time.

“What does it all mean?” he kept repeating mechanically.

Upon my honour I could not have enlightened him. Besides he did not ask me, and he went on talking to himself.

“This is what is called a cryptogram, or cipher,” he said, “in which letters are purposely thrown in confusion, which if properly arranged would reveal their sense. Only think that under this jargon there may lie concealed the clue to some great discovery!”

As for me, I was of opinion that there was nothing at ill in it; though, of course, I took care not to say so.

Then the Professor took the book and the parchment, and diligently compared them together.

“These two writings are not by the same hand,” he said; “the cipher is of later date than the book, an undoubted proof of which I see in a moment. The first letter is a double m, a letter which is not to be found in Turlleson’s book, and which was only added to the alphabet in the fourteenth century. Therefore there are two hundred years between the manuscript and the document.”

I admitted that this was a strictly logical conclusion.

“I am therefore led to imagine,” continued my uncle, “that some possessor of this book wrote these mysterious letters. But who was that possessor? Is his name nowhere to be found in the manuscript?”

My uncle raised his spectacles, took up a strong lens, and carefully examined the blank pages of the book. On the front of the second, the title-page, he noticed a sort of stain which looked like an ink blot. But in looking at it very closely he thought he could distinguish some half-effaced letters. My uncle at once fastened upon this as the centre of interest, and he laboured at that blot, until by the help of his microscope he ended by making out the following Runic characters which he read without difficulty.

“Arne Saknussemm!” he cried in triumph. “Why that is the name of another Icelander, a savant of the sixteenth century, a celebrated alchemist!”

I gazed at my uncle with satisfactory admiration.

“Those alchemists,” he resumed, “Avicenna, Bacon, Lully, Paracelsus, were the real and only savants of their time. They made discoveries at which we are astonished. Has not this Saknussemm concealed under his cryptogram some surprising invention? It is so; it must be so!”

The Professor’s imagination took fire at this hypothesis.

“No doubt,” I ventured to reply; “but what interest would he have in thus hiding so marvellous a discovery?”

“Why? Why? How can I tell? Did not Galileo do the same by Saturn? We shall see. I will get at the secret of this document, and I will neither sleep nor eat until I have found it out.”

My comment on this was a half-suppressed “Oh!”

“Nor you either, Axel,” he added.

“The deuce!” said I to myself; “then it is lucky I have eaten two dinners to-day!”

“First of all we must find out the key to this cipher; that cannot be difficult.”

At these words I quickly raised my head; but my uncle went on soliloquising.

“There’s nothing easier. In this document there are a hundred and thirty-two letters, viz., seventy-seven consonants and fifty-five vowels. This is the proportion found in southern languages, whilst northern tongues are much richer in consonants; therefore this is in a southern language.”