Полная версия:

Simple Stargazing

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

PART 1 GETTING STARTED

A Brief History

Constellations

Adventures in Darkness

Travels into the Darkness

How Big is the Darkness

How to Use the Star Charts

Bright or Dim?

Stars

Starry Objects

PART 2 THE NORTHERN CHARTS

January to March Skies

April to June Skies

July to September Skies

October to December Skies

PART 3 THE SOUTHERN CHARTS

January to March Skies

April to June Skies

July to September Skies

October to December Skies

PART 4 SUN, MOON AND PLANETS

The Moon

Eclipses

The Planets

Planets and Days

The Milky Way

Watching Satellites and the ISS

Comets

Shooting Stars

A Final View of Everything

Astro Glossary

Going Further

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

For Morten, Etienne and Dad

Introduction

Prepare yourself for an adventure… that will take you deep into space and far back in time. This great journey begins the moment you cast your eyes up into the night sky. After a while you’ll be looking beyond the stars, wondering about distant life or maybe thinking just how fantastically big this whole Universe thing is.

I vividly remember when I was six, gazing out of my bedroom window with a desire to learn the names of the bright stars and the patterns I knew existed in the form of constellations. Little did I know what I had started – a lifelong trip which never ceases to amaze me. We are now in the age of Hubble, Cassini, Galileo, Hipparchos and Messenger (etc., etc.) – spacecraft that open up the vistas of the Universe to realms that excite while causing us to constantly rearrange our jigsaw of… well, everything. And this is not going to slow down. Look out for specially trained astronauts on the Moon and Mars, and ‘ordinary’ astronauts (that’s you and me) taking short trips into space.

Hopefully I can share some of my wonderment through these pages. None of this is rocket science (apart from the rocket science stuff). The name of the stargazing game is easy, short observing whenever you have a few spare moments while the stars are twinkling overhead.

‘Oh, but I can’t see the stars from where I live,’ is always a good one. Read carefully, as this will be written only once: living in a town, city or anywhere with light-polluted skies need not deter anyone from stargazing. Although the sky glow washes out the fainter stars, the major constellations will still be visible. So you won’t be hindered from learning the main star patterns. No excuse there, then!

Don’t underestimate the power of ‘doing’ something. Simply by taking a few minutes each day over the course of a year you’ll soon be amazing your friends as you point out Leo and say, ‘Of course, Regulus is a B7-type star about 85 light-years away.’ Or you might glance at the Square of Pegasus, remarking casually, ‘Messier 15 over there was discovered by the wonderful Italian, Maraldi.’ Or even dreamily waft your hand in the direction of Orion, and with a certain authority launch into, ‘The dimensions of M42 are 66 by 60 arc minutes.’ It won’t take long to learn the night sky, and I hope this book will inspire you to make a start.

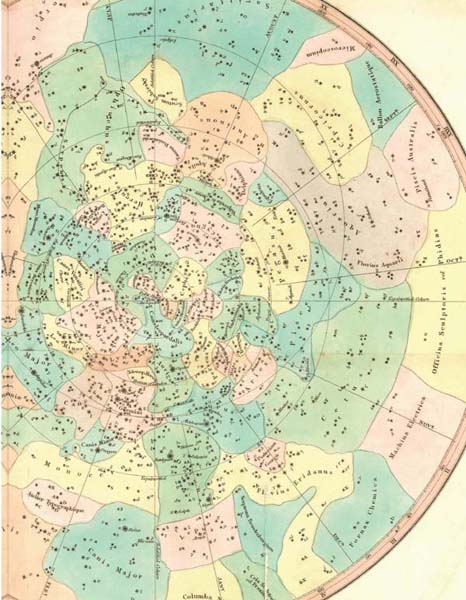

The night sky is out there. As this old map shows, it’s all prepared and ready for you to explore.

Part 1 Getting Started

A fine sunset is worth a picture itself as well as the hint that it’s going to be a fine, clear, starry-skied evening. Just the prompt you need to get you into the stargazing frame of mind.

A Brief History

In the distant past, astronomy and astrology were as one. Ancient rulers needed to know their fortune and, as the sky was where their gods lived, it was also where their destiny lay. Along with all the ‘fixed’ stars of the constellations were seven things that moved: the Sun, Moon and five planets – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn (this was, of course, in the days when everyone believed that the Earth was the centre of the Universe and other sky objects moved round it).

It was an absolute belief that leaders who could understand how these objects moved could stay in control and defeat their enemies. One thing was clear: to these ancient watchers of the skies these seven objects followed a ‘path’ around the heavens – just like a car on a race track that takes the same route round again and again. It was the constellations situated along this ‘path’ that became our 12 famous signs of the zodiac.

Of course, in order to know where any object would be in the zodiac at any given time, a certain amount of calculation was required. This is when the science of astronomy was born. So, strangely, the necessity for fortune-telling encouraged the formation of science. By the way, zodiac means ‘line of animals’ (11 of the original 12 constellations are still animals) and is also linked to the word zoo.

So, why do the planets, Sun and Moon appear to move through the skies? Well, they each appear to move for different reasons. Of course the main movement you see is due to the Earth spinning – this gives us things like sunset, the Full Moon rising over frosty trees, time for your cornflakes for breakfast as the Sun rises, etc. The Moon, if it is up, additionally appears to move extremely slowly hour by hour in front of the stars because it is orbiting the Earth. The Sun changes its position against the stars day by day due to the fact that we are orbiting it. The planets move because they too are orbiting the Sun – plus each planet is moving at a different speed. No wonder it was all difficult to calculate, and indeed it’s hardly surprising that some early astronomers ended up having their heads chopped off, when their erroneous adding up was followed by a total overreaction from their bad-tempered rulers.

Constellations

A word worth defining before we launch ourselves into space is constellation. It’s based on a word from Latin meaning ‘group of stars’. In total you’ll find 88 of them filling the entire sky, but thankfully you don’t need to know them all to enjoy the hours of darkness. Other starry terms that crop up throughout the book are written in bold and explained in the AstroGlossary in here.

The story of organising things up there in the darkness of the night began thousands of years ago with civilisations such as the Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks and Romans (as well as many other cultures from around the world). They decided the starry skies could do with a bit of order and a tidy up. So they joined up many of the stars, just like a dot-to-dot picture, putting their myths and legends into the sky as they did so.

Don’t think that there was any rhyme or reason for making a particular pattern. For example, Cepheus, King of Ethiopia, and his wife, Queen Cassiopeia, both have constellations named after them, and yet these look like a house and a set of stairs respectively. Imagination is the key here, I feel. As far as these early civilisations were concerned, the gods and goddesses needed a place to reside in the starry vault, so it was probably a case of first come, first served, and pot luck as to which stars were assigned to which group.

We get our earliest knowledge of the constellations from Aratos, the first Greek astronomical poet, in his work Phaenomena (which was probably based on an earlier ‘lost’ work by another Greek, Eudoxus). Then in AD 150 Ptolemy, a Greek working at the great library of Alexandria in Egypt, recorded them in a book known by its Arabic name, Almagest, which means ‘the greatest’. Hundreds of years ago, other astronomers who wanted to be famous added extra groups (some more successfully than others) to give us our present fixed total of 88 constellations.

Constellation names are traditionally written in Latin. This is because Ptolemy’s book was brought from the Middle East to Italy, where it was translated – and Latin, for centuries, was the language of scholars. So, for example, we know the Great Bear as Ursa Major.

Here are all the 88 constellations of the starry skies. Details of those with interesting things to see are given in Parts 2 and 3.

Latin Name English Name Abbreviation Order of Size(1 is the largest) Andromeda Andromeda And 9 Antlia Pump Ant 62 Apus Bee Aps 67 Aquarius Water Bearer Aqr 10 Aquila Eagle Aql 22 Ara Altar Ara 63 Aries Ram Ari 39 Auriga Charioteer Aur 21 Boötes Herdsman Boo 13 Caelum Sculptor’s Tool Cae 81 Camelopardalis Giraffe Cam 18 Cancer Crab Cnc 31 Canes Venatici Hunting Dogs CVn 38 Canis Major Great Dog CMa 43 Canis Minor Little Dog CMi 71 Capricornus Sea Goat Cap 40 Carina Keel Car 34 Cassiopeia Queen Cas 25 Centaurus Centaur Cen 9 Cepheus King Cep 27 Cetus Whale Cet 4 Chameleon Chameleon Cha 79 Circinus Drawing Compass Cir 85 Columba Dove Col 54 Coma Berenices Berenice’s Hair Com 42 Corona Australis Southern Crown CrA 80 Corona Borealis Northern Crown CrB 73 Corvus Crow CrV 70 Crater Cup Crt 53 Crux Cross Cru 88 Cygnus Swan Cyg 16 Delphinus Dolphin Del 69 Dorado Goldfish Dor 72 Draco Dragon Dra 8 Equuleus Little Horse Equ 87 Eridanus River Eri 6 Fornax Furnace For 41 Gemini Twins Gem 30 Grus Crane Gru 45 Hercules Hercules Her 5 Horologium Clock Hor 58 Hydra Water Snake Hya 1 Hydrus Little Snake Hyi 61 Indus Indian Ind 49 Lacerta Lizard Lac 68 Leo Lion Leo 12 Leo Minor Little Lion Lmi 64 Lepus Hare Lep 51 Libra Scales Lib 29 Lupus Wolf Lup 46 Lynx Lynx Lyn 28 Lyra Harp Lyr 52 Mensa Table Men 75 Microscopium Microscope Mic 66 Monoceros Unicorn Mon 35 Musca Fly Mus 77 Norma Level Nor 74 Octans Octant Oct 50 Ophiuchus Serpent Bearer Oph 11 Orion Hunter Ori 26 Pavo Peacock Pav 44 Pegasus Flying Horse Peg 7 Perseus Perseus Per 24 Phoenix Phoenix Phe 37 Pictor Painter Pic 59 Pisces Fish Psc 14 Piscis Austrinus Southern Fish PsA 60 Puppis Stern Pup 20 Pyxis Compass Pyx 65 Reticulum Net Ret 82 Sagitta Arrow Sge 86 Sagittarius Archer Sgr 15 Scorpius Scorpion Sco 33 Sculptor Sculptor Scl 36 Scutum Shield Sct 84 Serpens Serpent Ser 23 Sextans Sextant Sex 47 Taurus Bull Tau 17 Telescopium Telescope Tel 57 Triangulum Triangle Tri 78 Triangulum Australe Southern Triangle TrA 83 Tucana Toucan Tuc 48 Ursa Major Great Bear UMa 3 Ursa Minor Little Bear UMi 56 Vela Sails Vel 32 Virgo Maiden Vir 2 Volans Flying Fish Vol 76 Vulpecula Fox Vul 55