Полная версия:

Trajectories of Economic Transformations. Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

Trajectories of Economic Transformations

Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

Valery Kushlin

To Oksana, my beloved wife and

trusted companion for life

Kushlin Valery

Trajectories of Economic Transformations: Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond / Valery Kushlin. – Ekaterinburg : Издательские решения, 2024. – 346 p.

ISBN 978-5-0064-6474-2

The first English-language edition of a landmark 2004 work by a prominent Russian economist, Professor Valery Kushlin, offers profound insights into the painful challenges and crossroads of Russia’s post-socialist transition, nesting them in the 21st century’s emerging global socioeconomic trends and contradictions. Twenty years after the book’s original publication, its key observations on the nature of economic transformations strongly resonate in the context of contemporary global challenges.

Translated and edited by Andrey V. Kushlin, 2024.

Cover design by Ivan A. Zherebtsov, 2024.

All rights reserved.

© Valery Kushlin, 2024

ISBN 978-5-0064-6474-2

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

Introduction

The modern world economy is a complex combination of transnational structures and national economic systems of different scales and levels. There is much to be said about the increased interdependence of economic systems in the world and the dynamism of economic and socio-political changes. But no matter how economic interactions in the world change, most people judge them by what happens in their home country. The peoples of Russia, as well as the peoples of several other countries. In the last decade of the 20th century, they were involved in transformations that were very sensitive to them, which primarily took over the economy and, through this, all areas of people’s lives. These transformations were initiated by the conscious actions of the most active representatives of the country’s elites and tacitly supported by the people. From the very beginning, they acquired the character of purposeful changes in the economic system, so it became appropriate to talk about the policy of economic transformations.

Although these transformation processes started a long time ago, and mountains of literature have already been written about them, the comprehension of what is happening not only does not seem complete, but with each step from the old to the other, it gives rise to more and more questions that do not receive explanations. Among such questions are both directly mundane, pragmatic, related to the lives of people today and tomorrow, and conceptual, worldview, related to the understanding of the driving forces and patterns of qualitative and quantitative changes in the economy and society.

The focus is rightly on changes in the economic system, which also determine other qualitative features of society. In studying them, it is important to agree on fundamental approaches related to the understanding of the general and the specifics. Since economic transformations have occurred many times in the history of countries and peoples, there is a natural desire to use the facts of history and their systematization in literature to derive the laws of economic transformations. applicable to today. Such an approach cannot be excluded, but neither can it become the main method of analysis. The transformations of the economic system that have unfolded today in Russia and other post-socialist countries cannot be adjusted in terms of content and consequences to analogues in the past. They are truly unique and need to be approached in all their complex concreteness. It is also necessary to consider the very complex relationship between the transformation processes in the countries of the post-socialist zone and the rest of the world economy. These external blocs are influencing post-socialist countries more strongly than in the past, and not necessarily positively. The increasingly contradictory development of events in the world economy, including in the system of economies of countries that have always seemed stable, gives rise to expectations of serious transformations in themselves along not entirely clear trajectories.

These considerations have predetermined our approach to the chosen topic of economic transformation. We will talk about the content and methods of transforming the Russian economy as a particularly complex phenomenon that does not fit into some known schemes, but at the same time as a process that is part of contradictory economic and socio-political transformations around the world.

When analyzing such complex transformational phenomena, the question inevitably arises about their causes and effects, about real (and hidden) goals, and about the trajectories of progress towards them.

The word “trajectories” in the title of this book is somewhat symbolic. It denotes the need for the economic systems of all countries to move towards new states in order to overcome global contradictions, and at the same time emphasizes the limitations of managerial influences on these advances. It is no coincidence that the concept of “trajectory” is taken here in the plural. I proceeded from the fact that there are a great many ways to transform the economy in each country. Moreover, the endpoints of each of the trajectories are also not unambiguous, but multivariate. The goals achieved by economic transformations are clarified and concretized only in the course of the practice of transformations. This means that the analysis of transformation trajectories should include a constant clarification of the content of transformations and their goals.

In fact, today, when assessing economic transformations in Russia, they are guided by their comparisons with the situation in the developed countries of the West. But to what extent this benchmark can serve as an objective criterion of socio-economic progress, no one has a confident answer today.

For some time now, it has become axiomatic that the most efficient economy is a market-type economy, i.e., one based on the principles of self-regulation, on the automatic laws of supply and demand, and on individual interest as the engine of development. The assertion of the axiomatic nature of this truth was facilitated by the long-term practice of the dynamic development of the economies of the countries of the capitalist West against the background of the rest of the world. At the same time, however, the question of the price of this “effectiveness” was left unanswered, as it is associated with the unique conditions for consuming the potential of the world’s resources within the “model” countries. Nevertheless, practically all deviations from the supremacy of the principles of the Anglo-Saxon market, be they patriarchal economies, command economies, collective or socialist economic systems, have remained in the historical past and are considered to have lost the competition with the market capitalist economy. Hence the choice of ways to transform the economic systems of the countries of the socialist camp made in the last decade of the second millennium.

It was the processes of radical transformations of economic systems in the countries of the post-Soviet and post-socialist zones that gave rise to a special elaboration in the literature of a special category – “economic transformation” or simply “transformation.”1 Over the past decade, several publications have been issued in which the topic of economic transformations is brought to the level of theoretical generalizations2. Attempts are made to identify certain laws of economic transformations common to the long history of mankind. But the desire for universalization in the description of the laws of development is fraught with the generation of errors. The probability of such outcomes is high if theorizing on the topic of economic transformations begins to follow the path of logical analysis concepts or juxtapositions of phenomena that are similar to each other in form, but in fact, perhaps not of the same order.

In this book, the reader focuses on the understanding of specific processes of transformation of economic systems at the turn of the second and third millennia, which started in the former socialist countries because of the conscious actions of the elite of society. Their objective reason is the need to establish economic institutions that ensure higher economic efficiency and the growth of the well-being of peoples. In practice, however, the proclaimed reform plans have largely failed to materialize. A few contradictions of the old economy, such as insensitivity to scientific and technological progress (STP), heavier structure, as well as social problems, have become even more acute. Moreover, after 10—15 years, the content and trajectories of the transformations that have begun in many countries today do not look quite predictable. The economic downturn has been inexplicably large and long-lasting. There is a great gap between the people who have benefited greatly from the reforms (the minority) and the people who have clearly lost (the majority).

In the context of the obvious divergence of interests of the existing social groups, it is difficult to count on the coincidence of assessments of the effectiveness of economic transformations among different segments of society. The number of people who are dissatisfied with the transformations is very high, and many are inclined to criticize these processes at the conceptual level. There are reasons for this, because the role models – the economies of highly developed countries – are in many ways more discredited than before. Under the influence of the aggravation of contradictions, the uncertainty about the future of the peoples of formerly prosperous countries is increasing. Local and international financial and economic crises have become more frequent. In the full sense of the word, some respectable concepts of transition to a market economy developed by international institutions on the basis of classical schemes for developing countries and countries with economies in transition have gone bankrupt. A striking example is the widespread negative effectiveness of the transformation programs formed on the basis of the so-called Washington Consensus.

With the rejection of the alternative economic structure to capitalism, it seems that all systemic obstacles to the establishment of homogeneity of economic space on the entire planet and to the harmonious socio-economic development of the world along the well-trodden track are being removed. Meanwhile, the latter is just an appearance. In fact, there are growing contradictions associated with the unevenness of economic development, the struggle for limited resources, and the new scale and quality of structural changes in the global world.

World-renowned philosopher and sociologist Alvin Toffler argues that “the recent shifts in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union are only minor firefights compared to the global power struggle that lies ahead. And the competition between the United States, Europe and Japan has not yet reached its climax.”3

The development of events in the world in the first years of the third millennium showed unexpected and very tough conflict situations that manifested themselves in the “prosperous” spaces of Europe and America, not to mention the Middle East and Africa.

But so far, in the literature, the theme of the struggle for power, touched upon by Toffler, reflects the side of the contradictions between the present and the future, which is limited to the interests and lifestyle of the most highly developed countries of the world. The rest of the world is present in the arguments only as a general background, as a condition for the implementation of the strategies of highly developed countries. Such an accentuation of research is a typical feature of the works of modern social scientists living in the West: apparently, it reflects stable priorities of thinking that exclude the manifestation of a deep interest in the needs of peoples who are not included in the “golden billion.” Meanwhile, future processes in the world are not reducible to relations between the United States, Europe and Japan (for all their significance). The most unexpected turns in world processes may occur, which will be determined by the nature of the development and resolution of contradictions between the North and the South, between the West and the East, between transnational corporations (TNCs) and the rest of the world, between religions, etc.

So far, there has been almost no scientific research on the content and trajectories of possible transformations of the economic systems that have developed in highly developed countries. Most researchers and politicians prefer to think that everything in these countries will continue to follow the well-trodden path. However, given the real trends, there is less and less hope for such scenarios.

In this context, materials on economic transformations in post-socialist countries, especially analytical and evaluative materials on such a large-scale and truly complex country as Russia, are becoming increasingly important. They are important both for finding the right decisions regarding the outcome of the experiments that have been initiated and the fate of hundreds of millions of people living in these territories, and for eliminating the mistakes of “arrogance” on the part of global strategists. It just so happened that the course of history created a unique test site in the space of the former USSR and the former Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). This consideration was fundamental in shaping the idea of this book.

The book is based on materials on the economy in the former Soviet Union and, first of all, on materials from Russia. This emphasis is due, firstly, to the author’s personal interest as a citizen of his country, and secondly, to the author’s direct impressions of the behavior of high state structures both during the period of transformations and long before the collapse of the USSR. Thirdly, the author proceeds from the fact that it is the post-Soviet (especially Russian) transformations that today have a sufficiently representative factual base to make broader generalizations about hypotheses about the future of economic transformations in the world. Both the geopolitical position of the object of study (USSR, Russia) and the scale of the phenomena observed here during economic transformations provide grounds for global assessments.

An important circumstance that predetermines the choice of the vector of economic policy in specific countries and in the world is the correlation of forces of the functioning scientific and economic schools. Therefore, to the extent possible, when considering the main topics of economic transformations in Russia and in the world, the book traces the changes in the contours of economic thought that affect real life. Such an analysis is directed by the author to determine the scientific basis for the implementation of further economic transformations in Russia in the most effective way for the country.

Part I: Prerequisites and the Course of Transformations in Russia

Chapter 1. The Turn of the Millennium: A Time for New Directions

The transformation processes in Russia and other post-socialist countries began and unfolded at a time when the world of highly developed countries seemed to be rushing forward at full speed and ideally embodying the phenomenon of socio-economic progress. At the turn of the second and third millennia, however, the intellectuals of the world began to talk more and more often about the sense of a dead-end path based on the evolution of the age-old system of capitalist economy. The reason for this was the frequent economic and financial crises in various parts of the world economy, the aggravation of contradictions between competing centers of economic dynamics, including between traditional allies within the bloc of highly developed countries, the emergence of fundamentally new processes and forms in the global economy that cannot be explained within the framework of the usual scientific and economic concepts, the growing threats of energy (and resource shortages in general), and the lack of harmony between industrial development and the preservation of the human environment, the unevenness of scientific and technological progress (STP) and the ambiguity of its consequences for different countries and social strata.

The famous philosopher Jean Baudrillard, professor of sociology at the University of Paris, put it succinctly: “We are moving at an increasing speed, but we do not know where.”4

A Local Knot of Global Contradictions

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the aggravation of contradictions in socio-economic development manifested itself in all countries and regions of the world, but not simultaneously and with varying intensity. Despite the spurring effect of globalization, which has provided a significant head start to countries that have concentrated the potential of transnational capital on their territories, the world economy has not accelerated, but even slowed down. Average annual growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in the world fell from 3.1% in 1980—1990 to 2.0% in 1990—1995.

Let us name several more socially specific negative processes noted by international experts. First, there is a deepening inequality in the world. Average incomes in the richest 20 countries are now 37 times higher than in the poorest 20. That gap has doubled over the past 40 years, largely due to slow growth in the poorest countries. Similar phenomena of deepening inequality can be observed within many countries. An increasingly serious destructive factor is conflict situations have become more frequent. In the 1990s, more than half of the poorest countries were involved in conflicts, mostly civil conflicts. The result has been enormous losses, reversing the elements of progress and leaving a legacy of destruction and mistrust that undermines future opportunities. The relationship between nature and society has sharply deteriorated. Air pollution has reached critical proportions in many countries. Freshwater scarcity is increasing, with a third of the world’s population living in countries that already experience some or significant water scarcity. Since the early 1950s, nearly 2 million hectares of land (23% of the world’s arable and grazing land, forests, and wetlands) have been degraded. Deforestation of the land is proceeding at a significant rate (for example, since 1960, a fifth of all tropical forests have been destroyed). In many ways, there is a loss of biodiversity.5

Of course, these and many other problems did not come to the fore all at once. It is rather difficult to name the specific years of their crisis escalation, just as it is impossible to record the exact years when major corrective steps were initiated by governments or international organizations. It should be noted, however, that the period of heightened concern in the world about new problems coincided with the maturation and unfolding of fundamental transformations of economic systems in several developing countries and countries that have for some time been called countries with economies in transition. It can be argued that active actions on the part of the institutions of the international community to overcome the aggravated problems were asymmetrical, they acquired the character of correcting the situation mainly among those who did not get into the “mainstream,” who lagged the leaders in the field of technological progress and social development.

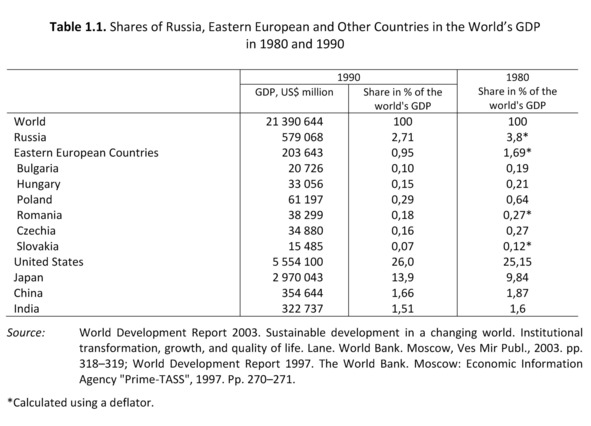

Russia and the other countries that made up the socialist system were among the first in the world to identify the most obvious economic contradictions. They manifested themselves in relief in the crisis of the extensive path of economic development, the inability to turn from which to a more adequate path of intensive type of expanded reproduction became a stumbling block for the countries of the Soviet bloc. And it is no coincidence that since the mid-1970s, in the USSR (and in Russia, which structured this union), in other socialist countries, there is talk of the dangers associated with a slowdown in economic growth. Table 1.1 shows that between 1980 and 1990, Russia’s already less impressive share of world GDP (compared, for example, with the United States or Japan) fell to 2.7%. The share of the other leading countries of the Eastern European bloc in world GDP fell to less than 1% in 1990.

Looking at the table, we notice while there was a slight decrease in the quota in the production of world GDP also in the United States and Japan. The shares of China and India also declined slightly during this period, but in the following years there was a steady increase in the economic weight of these countries.

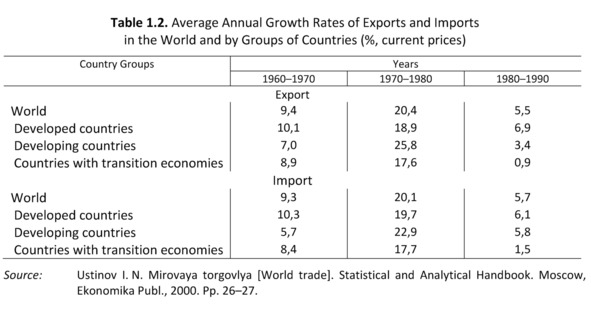

The contradictory course of events in the economies of the socialist countries is very clearly illustrated by the parameters of exports and imports. Table 1.2 shows that in 1980—1990 the average annual growth rates of exports and imports in the transition economies6 fell to symbolic values of 0.9 and 1.5%, respectively. At the same time, when considering three consecutive periods (1960—1970, 1970—1980, and 1980—1990), the nature of the dynamics of the average annual growth rate of exports and imports in transition economies is identical to those in developed and developing countries. However, the decline in the average annual growth rate of exports from 17.6% in the 1970s and 1980s to 0.9% in the 1980s and 1990s was egregious.

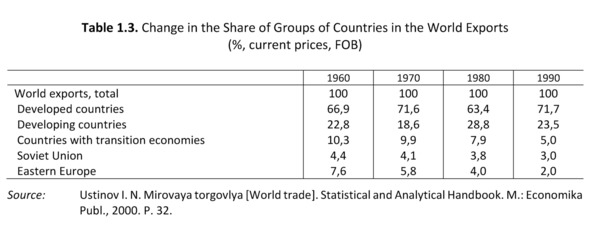

Table 1.3 shows how rapidly the share of transition economies, especially Eastern Europe, in world exports declined in the period after 1970.

In the context of the obvious aggravation of the problem of efficiency in the economies of the socialist countries, the decrease in their economic weight in the world economy and considering the increased desire among the elites of these countries to change the situation as quickly as possible, the active transformations of the economy that have begun here have become the center of the global search for new solutions. The conceptual dominant in transformation programs has been reduced to the formation and stimulation of market entrepreneurial forces on the model of the United States and other highly developed Western countries.

Transformations as systemic transformations in the economy and state structure unfolded differently in different countries and regions. In some places, for example, in Poland or the Soviet Baltic republics, political processes and demands came to the fore, followed only by radical economic reforms. In other cases, as in Hungary, for example, the process of economic reforms in the market direction was far advanced in the depths of the past, socialist system, and developed primarily in an evolutionary way. And in a completely evolutionary way, without the destruction of the political system, transformations developed in China. One way or another, the main content and motive of transformations and reforms was the formation of a market economy as a basis for familiarization with the values and lifestyle of highly developed countries of the West.

The totality of transformation processes in post-socialist countries appears to the observer, who undertakes to comprehend them, as a socio-political shift, which has no analogues in history. Nevertheless, the researcher must be able to rise above the abyss of events, otherwise the vector of objectivity will be lost.

Overcoming the euphoria inherent in the start of market reforms, it is impossible not to admit that the transformations that have unfolded in the post-socialist part of the world combine contradictory qualities: the uniqueness of the scope, on the one hand, and conceptual traditionalism, on the other. Indeed, the spatial scale of these transformations is impressive: they encompass at least a fifth of the Earth. They have begun to be implemented on the principle of almost instantaneous changes in the previous economic system, but, except for nuances, they are proceeding in different countries according to an almost uniform scenario in conceptual terms. In essence, transformations appear to be revolutionary only for the countries where they take place, and in a broader sense they are more than evolutionary, since they work by design, not to destroy, but to strengthen the prevailing traditional economic system.