скачать книгу бесплатно

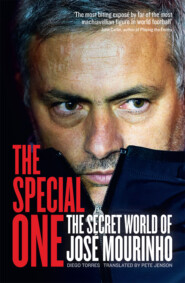

The Special One: The Dark Side of Jose Mourinho

Diego Torres

Pete Jenson

An explosive and shocking biography of Jose Mourinho - revealing the dark side of 'the special one'.When José Mourinho announced his return to English football, it sparked celebrations from fans and press alike. As one of the most charismatic figures in the game, his reappearance could surely only be a good thing…But is there a darker side to the Mourinho? A mischievous, scheming, even tyrannical quality to the man beneath the veneer of charm?As part of El Pais, Diego Torres is one of the premier investigative journalists in Spanish football, and in this explosive biography of 'the special one' he uncovers secrets and lies that will change the way we see Mourinho.From dodgy dealings to assassinations of players both outside and within his own team, and other shocking revelations, Prepare To Lose reveals Mourinho as a man far removed from the hero so many people consider him to be.

(#uf262fc09-2ee0-5f85-99b0-0ea07150a3f7)

Contents

Cover (#ud347be7e-274a-5d95-9a4f-4a1e07e4e7b2)

Title Page (#ulink_df70931e-2e2c-53cf-9e94-7349c6f20b58)

1 Crying (#ulink_fef57975-9e02-5759-91e5-8f0d4d80cec0)

2 Eyjafjallajökull (#ulink_ffcbaa93-620f-5442-932c-8ba4ba77a944)

3 Market (#ulink_149fbd6c-932c-5190-84ea-b03341899c5a)

4 Fight (#ulink_8dcb8157-43cb-5f82-80a8-575c8a3fd6f0)

5 Humiliation (#ulink_5f73ad7a-a2e8-5bfa-b078-ee7c4389672d)

6 Fear (#ulink_b1224d58-7f52-5e65-a6cd-5ba5b37c284a)

7 Prepare to Lose (#ulink_2fb7f1c5-e27e-5b25-95ef-024434d7f353)

8 Rebellion (#ulink_76905634-bfe4-5439-88db-6d958a6af0f1)

9 Triumph (#ulink_015462cd-7d22-54da-89ca-c07675b2b2b1)

10 Sadness (#ulink_4677b5c9-017b-5cf5-a00a-5c62119822c3)

11 Unreal (#ulink_1cc34fe6-0d67-541c-aba2-7572238e4906)

12 Blue (#ulink_33425dce-9e50-5e1c-860a-e7cddee3d9a5)

Copyright (#ulink_d6ff9ef6-55e1-51cb-9013-04d63925eb4e)

About the Publisher (#ubd4ea7fa-cd66-5031-b9b5-4d09936f97db)

Chapter 1

Crying (#uf262fc09-2ee0-5f85-99b0-0ea07150a3f7)

‘Think of this: When they present you with a watch they are giving you a tiny flowering hell, a wreath of roses, a dungeon of air.’

Julio Cortázar, ‘Preamble to the Instructions for Winding a Watch’

‘He was crying! He was crying …!’

Gestifute employee

On 8 May 2013, the employees of Gestão de Carreiras de Profissionais Desportivos S.A., Gestifute, the most important agency in the football industry, were to be found in a state of unusual excitement. José Mourinho kept calling employees. They had heard him sobbing loudly down the line and word quickly spread. The man most feared by many in the company had been crushed.

The news that Sir Alex Ferguson had named David Moyes as his successor as manager of Manchester United had caused an earthquake. United, the most valuable club in the world according to the stock market, were the equivalent of the great imperial crown of football marketing, and the position of manager, occupied for almost 27 years by a magnificent patriarch, had mythical connotations.

The terms of Ferguson’s abdication were the ‘scoop’ most coveted by the traffickers of the Premier League’s secrets. There were those who had toiled for years preparing a web of privileged connections to enable them to guess before anyone else when the vacancy would occur. Jorge Mendes, president and owner of Gestifute, had more ties with Old Trafford than any other agent. No agent had done as many deals, nor such strange ones, with Ferguson. No one had more painstakingly prepared an heir to the throne or succeeded in conveying the idea to the media that there was a predestined successor. If this propaganda had seeped into the consciousness of one man, that man was the aspiring applicant himself. Mourinho, encouraged by his devoted agent, believed that Ferguson was also an ally, a friend and protector. He became convinced that they were united by a relationship of genuine trust. He thought his own fabulous collection of trophies – two European Champion Leagues, one UEFA Cup, seven league titles and four domestic cups in four different countries – constituted a portfolio far outstripping those of the other suitors. When he learned that Ferguson had chosen David Moyes, the Everton manager, he was struck by an awful sense of disbelief. Moyes had never won anything!

These were the most miserable hours of Mourinho’s time as manager of Real Madrid. He endured them half asleep, half awake, glued to his mobile phone in search of clarification during the night of 7 to 8 May in the Sheraton Madrid Mirasierra hotel. He had arrived in his silver Audi in the afternoon along with his 12-year-old son, José Mario, with no suspicion of what was coming. On his left wrist he wore his €20,000 deLaCour ‘Mourinho City Ego’ watch, with the words ‘I am not afraid of the consequences of my decisions’ inscribed on the casing of sapphire crystal.

Mourinho was fascinated by luxury watches. He not only wore his sponsor’s brand – he collected watches compulsively. He maintained that you could not wear just any object on your wrist, stressing the need for something unique and distinguished intimately touching your skin.

That afternoon he was preparing to meet up with his team before playing the 36th league game of the season against Málaga at the Bernabéu. He was more than a little upset. He knew that his reputation as a charismatic leader was damaged, something he attributed to his stay in Chamartín. The behaviour of the Spanish seemed suffocating: the organisation of the club had never come up to his expectations and he was sick of his players. He had told the president, Florentino Pérez, that they had been disloyal, and to show his contempt he had decided not to travel with them on the team bus but make his own way to the hotel in a symbolic gesture that cut him off from the squad. He was met by members of the radical supporters’ group ‘Ultras Sur’, who unravelled a 60-foot banner near the entrance of the Sheraton. ‘Mou, we love you’, it said. When the squad arrived and the players began to file off the bus, one of the fans, hidden behind the banner, expressed the widespread feeling in this, the most violent sector of Madrid’s supporters.

‘Casillas! Stop blabbing and go fuck yourself!’

The suspicion that Casillas, the captain and the player closest to the fans, was a source of leaks had been formulated by Mourinho and the idea had penetrated to the heart of the club. Perez and his advisors claimed that for months the coach had insisted that the goalkeeper had a pernicious nature. When the suspicion was reported in certain sections of the media, the club did very little to rebuff it. The subject was the topic of radio and television sports debate programmes; everyone had an opinion on the matter except the goalkeeper himself, whose silence was enough to make many fans believe he was guilty. To complete his work of discrediting Casillas, Mourinho gave a press conference that same afternoon, suggesting that the goalkeeper was capable of trying to manipulate coaches to win his place in the team.

‘Just as Casillas can come and say, “I’d like a coach such as Del Bosque or Pellegrini, a more manageable coach,”’ he said, ‘it’s also legitimate for me to say the same thing. As the coach it’s legitimate for me to say, “I like Diego López.” And with me in charge, while I’m the coach of Madrid, Diego López will play. There’s no story.’

The atmosphere at the Sheraton was gloomy that night, with contradictory rumours from England circulating about the retirement of Ferguson. The online pages of the Mirror and Sun offered a disturbing picture. Mourinho was certain that if Sir Alex had taken such a decision he would have at least called to tell him. But there had been nothing. According to the people from Gestifute who lent him logistical support he had not received as much as a text message. The hours of anxiety were slowly getting to him, and he made calls until dawn to try to confirm the details with journalists and British friends. Mendes heard the definitive news about Ferguson straight away from another Gestifute employee but did not dare tell Mourinho the truth – that he had never stood the slightest chance.

Mourinho was tormented by the memory of Sir Bobby Charlton’s interview in the Guardian in December 2012. The verdict of the legendary former player and member of the United board had greatly unsettled him. When asked if he saw Mourinho as a successor to Ferguson, Charlton said, ‘A United manager would not do what he did to Tito Vilanova,’ referring to the finger in the eye incident. ‘Mourinho is a really good coach, but that’s as far as I’d go.’ And as far as the admiration Ferguson had for Mourinho was concerned, the veteran said it was a fiction: ‘He does not like him too much.’

Mourinho preferred to believe the things that Ferguson had personally told him rather than be bothered by what a newspaper claimed Charlton had said. But that night, the venerable figure of Sir Bobby assaulted his imagination with telling force. Mourinho had turned 50 and perhaps thoughts of his own mortality crossed his mind. There would be no more Manchester United for him. No more colossal dreams. Only reality. Only his decline in Spain devouring his prestige by the minute. Only Abramovich’s outstretched hand.

In the morning he called Mendes, asking him to get in touch with United urgently. Right until the end, he wanted his agent to exert pressure on the English club in an attempt to block any deal. It was an act of desperation. Both men knew that Mendes had put Mourinho on the market a year ago. David Gill, United’s chief executive, had held regular talks with Gestifute and was aware of Mourinho’s availability but he was not interested in him as a manager. He had told Mendes in the autumn of 2012 that Ferguson’s first choice was Pep Guardiola and had explained the reasons. At Gestifute, the message of one United executive seemed particularly pertinent: ‘The problem is, when things don’t go well for “Mou”, he does not follow the club’s line. He follows José’s line.’

What most frightened Mourinho was that public opinion would conclude he had made a fool of himself. He felt cheated by Ferguson and feared people might stop taking him seriously. For years, the propaganda machine acting on his behalf had made quite a fuss of the friendship between the two men; this was now revealed to be a fantasy. To make these latest events seem coherent, Gestifute advisors told him to say that he already knew everything because Ferguson had called to inform him. On 9 May someone at Gestifute got in touch with a journalist at the daily newspaper Record to tell them that Ferguson had offered his crown to Mourinho four months ago, but that he had rejected it because his wife preferred to live in London, and for that reason he was now leaning towards going back to Chelsea. Meanwhile, Mourinho gave an interview on Sky in which he stated that Ferguson had made him aware of his intentions, but never made him the offer because he knew that he wanted to coach Chelsea. The contradictions were not planned.

From that fateful 7 May onwards Mourinho was weighed down by something approaching a deep depression. For two weeks he disappeared from the public eye and barely spoke to his players. For the first time in years, the Spanish and the Portuguese press – watching from a distance – agreed that they were watching a lunatic. On 17 May Real played the final of the Copa del Rey against Atlético Madrid. The preparation for the game made the players anticipate the worst. The sense of mutual resentment was overbearing. If Mourinho felt betrayed, the squad saw him as someone whose influence could destroy anyone’s career. If he had jeopardised Casillas’s future, the most formidable captain in the history of Spanish football, how were the other players to feel? A witness who watched events unfold from within Valdebebas described the appalling situation: the players didn’t mind losing because it meant that Mourinho lost. It didn’t matter to Mourinho, either, and so they lost.

On 16 May the manager showed up at the team hotel with a sketch of a trivote under his arm. ‘Trivote’ was the term the players used to describe the tactical model that Mourinho claimed to have invented. It was executed by different players according to the circumstances. The plan, presented on the screen of the hotel, had Modrić, Alonso and Khedira as the chosen trio in midfield. This meant that the team’s most creative player, Özil, was shifted out to the right to a position where he felt isolated. Benzema and Ronaldo were up front. Essien, Albiol, Ramos and Coentrão were to play at the back, with Diego López in goal.

Mourinho’s team-talks had always been characterised by a hypnotic inflammation. The man vibrated. Every idea that he transmitted seemed to be coming directly from the core of his nervous system. That day this did not happen. He had spent a long time isolated in his office – absorbed, sunken-eyed, pale, melancholic. The players were at a loss as to why. Some interpreted it as sheer indolence, others saw him as quite simply lost, as if he were saying things he did not understand.

‘He looked like a hologram,’ recalled one assistant.

‘All that was missing was a yawn,’ said another.

The room fell into a tense silence. The coach was proposing something on the board that they had not practised all week. Incomprehensible, maybe, but a regular occurrence in recent months. He told them that after years implementing this system they should understand it so well that they didn’t need to practise it. They would have to content themselves with understanding how he wanted them to attack. As usual, the most complex job was allocated to Özil. The German had to cover the wing when the team did not have the ball. When possession was regained he had to move to a more central position and link up with Modrić.

The players understood that to gain width and get behind Atlético the logical thing would have been to put a winger on the right, somebody like Di María, leave Özil in the centre and drop Modrić back into Khedira’s position. But the coach believed that because Modrić lacked the necessary physical attributes, he needed to support the defensive base of the team with Khedira. No one spoke up against the plan. For years the communication between the leader and his subordinates had been a one-way street.

This time, however, it was because there was just nothing to say. The team-talk was brief. The players were left wondering why on earth they had to defensively reinforce the midfield with Khedira against an Atlético side who were hardly going to attack them. But, mute, they merely obeyed.

For the club with the largest budget in the world, the Copa del Rey was a lesser objective. Finding out that the final would be played in their stadium distressed the directors. After losing the league and the Champions League, the season had little left to offer. A final against Atlético in Chamartín was in many ways a no-win situation. The joke had been doing the rounds since the team beat Barça at the Camp Nou to qualify, that the president had been heard to say that a final in the Bernabéu against Atlético was about as attractive as a ‘punch bag’.

The ticket prices fixed by the clubs and the Spanish Football Federation set a new record. Despite the economic crisis that was crushing Spain this was the most expensive cup final in history. Prices ranged from €50 to €275. Attending the FA Cup at Wembley cost between €53 and €136, and German cup final tickets went from between €35 and €125. At the Coppa Italia the price ranged from €30 to €120. That afternoon, as was to be expected, there were empty seats.

Ronaldo headed in a Modrić corner, putting Madrid 1–0 up in the 14th minute. Following to the letter instructions that were now three years old, the team retreated to protect the lead, giving up space and possession to their opponents. Their opponents’ situation looked impossible. Madrid had a more expensive constellation of star players than had ever been brought together. And against them they did not have the Atlético of Schuster, Vizcaíno, Donato, Manolo and Futre that had faced them in the final of 1992. Here instead were was Koke Resurrección, Gabi Fernández, Mario Suárez, Falcao, Arda and Costa. For an hour and a half, both teams cancelled each other out in the most extravagant manner possible. They tried to see who could go for longer without the ball. It was a fierce competition. Atlético dropped their level of possession to 40 per cent. Madrid had the remaining 60 per cent, but did not know how to manage it because Marcelo had been marginalised, Alonso was tired, Özil was suffering off-radar and Khedira was unable to channel the team’s attacks. Atlético took cover and in two lightning counter-attacks settled the match. First, Diego Costa scored after Falcao had taken advantage of a mistake by Albiol. Then, in extra time, Miranda headed in to make it 2–1, after Diego López made an error coming off his line.

Albiol had replaced Pepe, left out and watching from the stands because of his insurrection. Pepe called for more ‘respect’ to be shown to Casillas and in response was cleansed. Within hours the defender went from being the manager’s right-hand man on the pitch to becoming the object of a public trial.

The emergence of rising star Varane was the excuse. ‘It’s not easy for a man of 31 years, with a standing and a past, being steamrollered by a child of 19 like Varane,’ said Mourinho. ‘But it’s the law of life.’

Varane could not play in the final because of injury. Even so, Pepe watched the game from the stands, giving up his place to Albiol, who had not played regularly for months. Some of the players believed they recognised in this decision the clearest evidence that part of Mourinho’s selection-process was based on a dark code of loyalty even when it was to the detriment of the functioning of the team.

When the referee sent Mourinho off for protesting, Pepe went down to the bench and, in complete violation of the regulations, installed himself in the technical area. It was unprecedented behaviour as he took over from Aitor Karanka, the assistant coach, giving instructions to his colleagues from the touchline as if he were the manager. Not that it prevented an Atlético victory.

Karanka remained confused all evening. His boss had departed the stage, leaving him alone. Breaking protocol, Mourinho did not go up to receive the medal that King Juan Carlos had prepared to honour the coach of the losing team. Instead, it was Karanka who came up the stairs in front of the defeated players. On seeing him, the king grabbed the piece of silver and turned to the Spanish Football Federation president Ángel María Villar, seeking clarification:

‘Shall I give it to him?’

And so it was an embarrassed Karanka who received the salver, while Mourinho went to the press conference room to pronounce his final words as the official representative of Madrid. Three years of stirring rhetoric, shrill speeches, sessions of indoctrination, warnings, complaints and entertaining monologues were interrupted by a confession. There was no hiding from the fact that in his final year he had won nothing.

Never in the history of Real Madrid had a coach been more powerful and yet more miserable; nor one more willing to terminate his contract with the club, happy to end an adventure that had become a torment.

‘This is the worst season of my career,’ he said.

Chapter 2

Eyjafjallajökull (#uf262fc09-2ee0-5f85-99b0-0ea07150a3f7)

‘It is easy to see thou art a clown, Sancho,’ said Don Quixote, ‘and one of that sort that cry “Long life to the conqueror!”’

Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

The objective qualities of José Mourinho the coach were not what led Real Madrid to sign him in 2010. It was more that they considered him to be a magical, providential figure blessed with an unfathomable and mysterious wisdom.

Madrid’s director general, José Ángel Sánchez, was the main driving force behind the recruitment and the process took years to reach its conclusion. Perhaps it started in the first months of 2007 when Sánchez made contact with Jorge Mendes, Mourinho’s agent, to negotiate the transfer of Pepe. Képler Laverán Lima, nicknamed ‘Pepe’, was the Porto defender who cost €30 million, becoming the third-most expensive central defender in history after Rio Ferdinand and Alessandro Nesta. It was the highest price ever paid for a defender who had not played in his national team, and the first transaction concluded by Mendes and Sánchez, laying the foundations for a new order. From that moment on the super-agent began to redirect his strategy from England to Spain, those ties of friendship with Sánchez paving the way for the change.

Mendes did not delay building his relationship with Ramón Calderón, Madrid’s president between 2006 and 2009. Bold by nature, the Portuguese agent made him the inevitable offer: he would bring his star coach – at the time, running down his third season at Chelsea – to Madrid.

‘Once you get to know him you’ll not want to hire anyone else,’ Mendes encouraged. ‘If you want to prolong your spell at Madrid, you’ll have to bring in the best coach in the world.’

That is how Calderón remembers it, recalling how Mendes tried to organise a dinner with Mourinho. They promised him a lightning trip to a meeting in a chalet on the outskirts of Madrid in the dead of night to avoid photographers and maintain absolute secrecy. ‘José Ángel was utterly convinced,’ recalls Calderón, who says he looked into the idea with the director general and with Pedrag Mijatović, who at the time was Madrid’s sporting director.

‘This guy is going to drive us crazy!’ said the president. ‘With Mourinho here you won’t last a minute, Pedrag!’

Calderón did not employ any particularly logical reasoning to reject Mourinho. He simply thought of him as a difficult character with outdated ideas. ‘He’s like a young Capello,’ he said, vaguely alluding to a way of playing the game that bored the average fan. The ex-president did not account for the importance of charisma in arousing a crowd eager for Spanish football to regain its pre-eminence. A multitude increasingly in need of a messiah.

Mendes’s capacity for hard work is renowned. He promoted Mourinho in various European clubs when he had still not ended his relationship with Chelsea and continued to offer him around with even greater zeal from the winter of 2007 to 2008. At that time Barça were looking for a coach. Ferrán Soriano, now the executive director of Manchester City, was Barcelona’s economic vice president. Soriano explains that the selection process began with a list of five men and came down to a simple choice: Guardiola or Mourinho.

‘It was a technical decision,’ emphasises Soriano. ‘Football is full of folklore but in this instance you cannot say that it was an intuitive choice. Instead, it was more the product of rational and rigorous analysis. In Frank Rijkaard we had a coach who we liked a lot but we could see that his time was coming to an end. Frank took a team that was nothing and won the Champions League. He inherited a side with Saviola, Kluivert and Riquelme that had finished sixth, and then he won the league and the Champions League.

‘The following year the team’s level dropped a little. A 5 per cent drop in commitment at the highest level creates difficulties and Frank didn’t know how to re-energise the group. In December we decided to make a change. Mourinho had left Chelsea and there were possibilities to bring him in in January but we thought that it made no sense. We had to finish the season with Frank and give the new coach the opportunity to begin from scratch. Txiki was charged with the task of exploring alternatives and he went to various people: to Valverde, to Blanc, to Mourinho …’

Joan Laporta was the Barça president who conducted the operation and Txiki Begiristain, ex-Barcelona player and the then technical director, organised the interviews. Txiki met Mourinho in Lisbon and, after hearing his presentation, told him that Johan Cruyff would have the last word. The legendary Dutch player was at the time the club’s oracle. In the political climate that had always enveloped Barcelona, the presence of a figure whose legitimacy transcended the periodic presidential elections served to prop up risky decisions. The only person who enjoyed the necessary prestige to play that role was Cruyff.

Impatient ahead of the possibility of a return to the club in which he had worked between 1996 and 2000, Mourinho called Laporta: ‘President, allow me to speak with Johan. I’m going to convince him …’ Laporta got straight to the point and confessed that the decision had already been taken. The new coach would be Pep Guardiola. The news completely threw Mourinho, who told him that he had made a serious mistake. Guardiola, in his opinion, was not ready for the job.

Soriano describes the decisive moment: ‘After going through all the coaches that Txiki had examined, the conclusion was that it came down to two. In the end there was a meeting in which it was decided that it would be Guardiola, based on certain criteria.

‘We had put together a presentation and produced a document: what are the criteria for choosing the coach? It was clear that Mourinho was a great coach but we thought Guardiola would be even better. There was the important issue of knowledge of the club. Mourinho had it, but Guardiola had more of it, and he enjoyed a greater affinity with the club. Mourinho is a winner, but in order to win he generates a level of tension that becomes a problem. It’s a problem he chooses … It’s positive tension, but we didn’t want it. Mourinho has generated this tension at Chelsea, at Inter, at Madrid, everywhere. It’s his management style.’

In his book The Ball Doesn’t Go In By Chance, published in 2010, Soriano details the principles that led the club to choose Guardiola: 1. Respects the sports-management model and the role of the technical director; 2. Playing style; 3. Values to promote in the first team, with special attention to the development of young players; 4. Training and performance; 5. Proactive management of the dressing room; 6. Other responsibilities with, and commitments to, the club, including maintaining a conservative profile and avoiding overuse of the media; 7. Has experience as a player and coach at the highest level; 8. Supports the good governance of the club; 9. Knowledge of the Spanish league, the club and European competition.

Guardiola did not meet the seventh criterion, but then neither did Mourinho. What is more it was very unlikely, given past behaviour, that Mourinho could do the job without violating the second, third, sixth and eighth criteria.

The naming of Pep Guardiola as the Barça coach on 29 May 2008 marked Spanish football’s drift towards politicisation. This was paradoxical because Guardiola, one of the coaches most obsessed with the technical details of the game, an empiricist whose strength lay in his work on the pitch, began to be perceived by a certain section of Madrid supporters as an agitator, a manipulative communicator whose propaganda needed to be countered off the pitch. Distracted by this misconception, Madrid would expend much of its institutional energy on taking the necessary steps to wage war in the media.

While Guardiola started an epic landslide that would transform football across half the planet and contribute to reinforcing Spain’s national team as it conquered the world in 2010, institutional and social peace at Madrid became ever more scarce. Calderón, who hired Bernd Schuster, resigned a year and a half later amid accusations of corruption. Florentino Pérez, returning to the presidency in 2009, prompted a criminal investigation that led only to a ruling that Calderón had been the victim of slander and that he was not corrupt.

The return of Pérez to the Bernabéu signalled major changes. The president of the multinational construction firm ACS possessed an incomparable combination of determination and influence. In 2010 Forbes classified his fortune as the tenth largest in Spain. His origins, however, conform more to the petty bourgeoisie. A graduate of Madrid’s School of Civil Engineering, he formed part of a line of technocrats who have nurtured Spanish administration over the last two centuries. Affiliated to the Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), he entered politics in 1979, becoming a Madrid councillor, director general of the Ministry for Transport and Tourism, and undersecretary at the Ministry of Agriculture between 1979 and 1982. In 1986 he abandoned politics to begin a career in the private sector.

Unorthodox and adventurous in the management of sporting affairs, Pérez’s reputation was being increasingly challenged by his followers. Madrid had followed a downward trajectory under his direction between 2000 and 2006. From the initial peak of winning two league titles and a Champions League, the club had stagnated. After three years of failing to win a trophy, he handed in his resignation in February 2006, claiming that he had indulged his players like spoiled children and that it was necessary to install another helmsman, who, without the same sentimental attachment, would be capable of purging the dressing room. Never before in Madrid’s history had a president resigned in the middle of his mandate. But with a stubbornness to regain control of the directors’ box, and an avowed sense of mission, he returned to the club in 2009, although he was not chosen by members because the absence of any other candidates meant there was no election. He was 62 years old and assured supporters that, thanks to his intervention, Madrid had been saved from administrative crisis and financial ruin.

Back in power, Pérez set about hiring a new coach. He began the selection process advised by his right-hand man, the sporting director Jorge Valdano. After failed attempts to sign first Arsène Wenger and then Carlo Ancelotti, Pérez signed Manuel Pellegrini. The Chilean’s switch to Chamartín was preceded by suspicion and disaffection. He had still not completed half a season as first-team coach, and the idea of signing Mourinho was occupying Sánchez’s mind more than ever. The operation had been thought through over a period of several years and he was now close to convincing the president to take the plunge. In meetings with friends the director general sighed: ‘I love him!’

Valdano, however, insisted on protecting Pellegrini. The coach had been the subject of a smear campaign in the press, encouraged from within the club. During internal debates Sánchez identified Pellegrini as being inherently weak and too fragile to resist the rigours of the Madrid job. To convince Pérez, the director general reasoned, ‘Pellegrini needs protection because he’s weak. A strong man would not need protection.’

Sánchez took a two-pronged approach. He maintained contact with Mendes and he established a direct line of communication between the Inter coach and Pérez. When some raised suspicions over the suitability of Mourinho’s technical footballing knowledge to the Madrid team, Sánchez confessed that he believed Mourinho’s personality alone would make him worthy of a blockbuster production, while producing statistics to support his technical expertise.

‘I don’t know how much he knows about football,’ he said, ‘but a man who’s not lost a home game in six years must have something. Six years without losing in his own stadium! If he doesn’t know anything about football then he must know a lot about human beings. In his last game for Chelsea both Terry and Lampard ran to embrace him. That’s just not normal. Both of the team’s leaders!’

Sánchez is the mastermind behind the project that, between 2000 and 2007, turned Madrid into the richest football institution on the planet. His keen sense of humour co-exists with his zeal for his position. On one occasion in 2010 he presented himself in the following written terms: ‘I have been an executive director general for the last five years. Before that I was marketing director general for five years. My responsibility is corporate: the administration, the management, the resources, the facilities and infrastructure of the club, the general services, the purchasing, the information systems and technology, the human resources, the commercial and marketing department, areas of content, internal media, use of facilities, sponsors, etc. I am responsible for 141 of the 190 employees at the club. I am responsible for the economic results, the accounts, etc. I direct the club in these areas and take a certain pride that for six years we have topped the income ranking, including in the bad years or through periods of institutional crisis. I have negotiated the signings and the sales made by the club over the last 10 years … maybe 70 transactions in total. I negotiate the players’ contracts, the tours, the TV rights. I represent the club in the LFP (Professional Football League) and in the relevant international bodies. I have a certain disregard for the role of protagonist; I would even say I resent it … I have worked with different presidents, something that is significant in itself. In this transition (certainly an unusual experience in football) you make many friends, from Platini to Rummenigge, from Galliani to Raúl, from the president of Volkswagen to Tebas through to Roures, or a government minister, many businessmen, and football agents … That expanse of contacts just a phone call away is one of the strengths of the club.’

A philosophy graduate who cut his teeth in business administration with Sega, the electronic games company, serving as head of operations in Southern Europe, Sánchez is the most influential executive in Spanish football. When Pérez hired him for the club in the spring of 2000 he was 32 years old. Nobody imagined then that Pérez was preparing the ground for the development of someone who would dominate the Spanish league with an iron fist from 2006 onwards, contributing to the rapid enrichment of Madrid – and Barça – and, as a consequence, putting the finances of the other clubs in the Spanish league at serious risk. If the unequal distribution of TV income in Spain is something unique in Europe then that is in large part thanks to Sánchez’s ability to take advantage of the entanglement of delay, carelessness and incompetence spun by the three institutions that should be ensuring football’s economic health: the Ministry for Sport, the Spanish Football Federation and the Professional Football League.

Madrid’s chief executive since 2006, Sánchez radiated all the enthusiasm of a young lover as he considered Madrid’s future: the possibility of fusing the economic power of the world’s most popular club with the taste for propaganda of a coach capable of surpassing the publicity extravaganzas of any of the companies with which he had previously been involved. His spirit of curiosity was intrigued. Enthusiastic by nature, this master of marketing understood that he had uncovered possibilities hitherto untapped in the world of sport. It would be a pioneering experiment.

Sánchez needed to finish convincing Pérez when events took an intimidating turn. The elimination of Madrid from the Champions League last-16 against Lyon in March 2010 began to erode the president’s normally serene spirit. Barcelona were still on their way to a final that this year would be played at the Bernabéu. The possibility of an arch-rival – and Guardiola – winning their fourth Champions League in Chamartín was an outrage for Madrid’s more closed-minded supporters and an unbearable affront to Pérez.

Barcelona’s advance shifted the balance of power in Spanish football away from the capital. For the first time in 50 years Real Madrid, the club with the greatest number of European trophies, were no longer the reference point. This change in dominance, just when the Spanish national team was enjoying a golden era at all levels, led to inevitable political consequences. In many sectors of Spanish society, heavily influenced by nationalist sentiment, the presence of a Catalan club at the vanguard of the most popular sport in the country inspired a dark malaise.

UEFA had given the 2010 final to Madrid as a reward for Calderón’s efforts to improve the institutional relations between the Spanish Football Federation and the officials of European football’s governing body, headed by Michel Platini. For Pérez, since taking over as president, the organisation of the event – an uncomfortable inheritance from his predecessor – had become an unpleasant obligation and, ultimately, a trap.

The Madrid president’s overriding concern that Barcelona would end up playing in the final meant Mourinho became an object of veneration as soon as the draw had been made. If Barça wanted to get past the semi-finals they would have to overcome Inter, the team managed by the director general’s favourite. At this point, disappointed with Valdano after Pellegrini’s failings in domestic cup competition and in Europe, Sánchez and Pérez began to share the same technocratic feeling. A type of force-field united them in one vision in which football as a business was far too important to be left in the hands of mere football people such as Valdano, the sporting director and principal sporting authority at the club.

Valdano had an extensive CV. A world champion with Argentina in 1986, a league champion and UEFA Cup winner as a player, and a league winner as a coach, he knew all the mechanisms that moved Madrid. He used to say – and his opinion was shared by those agents who knew all concerned parties – that neither Pérez nor Sánchez had any deep analytical understanding of the game. Both marvelled at the stand-out players, the most elegant or the most skilful ones, but they struggled to understand why things happened the way they did during a match. In a crisis, under pressure, they would end up rejecting anything that didn’t dazzle and simply rely on their intuition. The models, the formulas and the sixth sense that had made them renowned executives fused with the historical necessity of stopping Barça. Mourinho, the man with the wistful gaze, was seen as the providential hero.

The repetitive discussions about Mendes and Mourinho had hit their target. There is no doubt that Pérez met with his future coach when Mourinho was still working at Inter. And even more certain is that the president had to listen to his director general explain why Mourinho was a great coach. ‘He has an intelligence for football that I’ve never seen in anyone else,’ said Sánchez at the time. He insisted that Mourinho knew exactly what each player could give and that he was able to anticipate what was going to happen in a game – that he was able to predict what would take place after half an hour, an hour, an hour and a half of play. He was ‘amazing’. Sánchez’s awe for a man he described as an omniscient magician always seemed genuine. Mourinho never went into too much detail, at least not in public. He never talked about what the training sessions were like or what his principles were, or what exactly was to be expected of his teams when planning matches. The only thing he knew for sure was that he had won a lot. Why ask so many questions when the trophies speak for themselves?

The eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in the south of Iceland on 20 March 2010 was an unexpected stroke of good fortune. The ash ejected into the atmosphere meant European air space was closed and Barcelona had to travel to Milan by bus. The team took a day getting there and spent two nights sleeping in hotels before the match. That would be significant in terms of performance levels in a competition decided by the smallest details. The 3–1 win from the first leg and the 1–0 defeat in the return gave Inter victory over 180 minutes of football in which they rarely dominated Barça. The fact that Inter finished the second leg with 10 men, hemmed into their own area, desperate, saved by the incorrect ruling-out of a Bojan goal, was not enough to make Pérez and Sánchez suspect that luck had played an important part. Barcelona’s defeat was such a relief to the president that he immediately closed the deal with Mourinho, convinced he was acquiring two magic spells for the price of one: the universal antidote to failure, and the ‘know how’ that would destroy Guardiola’s team.

‘Ilusión’ is the key word in all of Pérez’s public addresses since first becoming president. It means ‘excitement’, ‘hopeful anticipation’, ‘enthusiasm’. In his speech after winning the election on 17 July 2000 he said, ‘We have in front of us, just as we said in our election campaign, an exciting job full of ilusión.’ On 13 May 2009, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency, he spoke beneath a poster that displayed the project’s slogan, ‘The Ilusión Returns’, as if everything that had occurred since he had been away had been turgid and sterile. In his speech at the Salón Real at the Ritz Hotel he confided that he felt capable of ‘almost everything’, and warned he had ‘spectacular’ plans. The word ‘spectacular’ appeared five times in his speech. The day he announced the signing of Mourinho he insisted, ‘What I love about Mourinho are the same things that you are going to love: ilusión, effort, professionalism, motivation, aptitude … everything that makes him the best coach.’