Полная версия:

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Tom Burgis 2015

Tom Burgis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

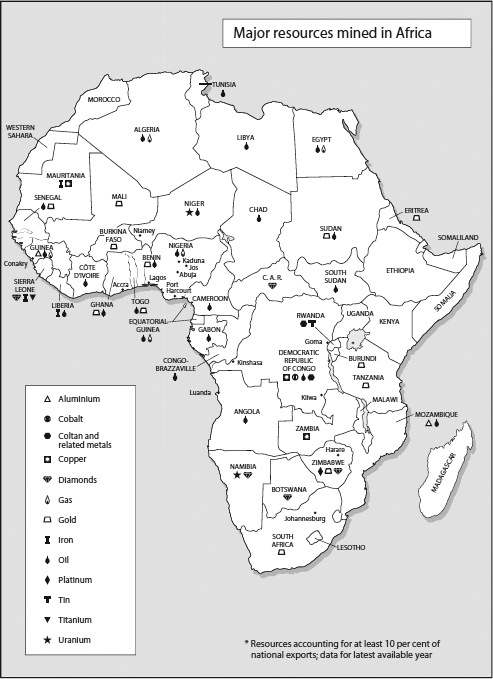

Map © John Gilkes

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007523108

Ebook Edition © April 2016 ISBN: 9780007523115

Version: 2016-02-29

Dedication

FOR MY MOTHER AND FATHER,

FAND THEIR KITCHEN TABLE

Author’s Note

IN LATE 2010 I started to feel sick. At first I put the constant nausea down to a bout of malaria and a stomach bug I’d picked up during a trip a few months earlier to cover an election in Guinea, but the sickness persisted. I went back to the UK for what was meant to be a week’s break before wrapping up in Lagos, the Nigerian megacity where I was based as the Financial Times’s west Africa correspondent. A doctor put a camera down my throat and found nothing. I stopped sleeping. I jumped at noises and found myself bursting into tears. At the end of the week I was walking to a shop to buy a newspaper for the train ride to the airport when my legs gave way. I postponed my flight and went to another doctor, who sent me to a psychiatrist. In the psychiatrist’s office I started to explain that I was exhausted and bewildered, and I was soon sobbing uncontrollably. The psychiatrist told me I had severe depression and that I should be admitted to a psychiatric ward immediately. There I was put on diazepam, a drug for anxiety, and antidepressants. After a few days in the hospital it became apparent that there was something else tormenting me in tandem with depression.

Eighteen months earlier I had travelled from Lagos to Jos, a city on the fault line between Nigeria’s predominantly Muslim north and largely Christian south, to cover an outbreak of communal violence. I arrived in a village on the outskirts not long after a mob had set fire to houses and their occupants, among them children and a baby. I took photographs, counted bodies, and filed my story. After a few days trying to understand the causes of the slaughter, I set off for the next assignment. Over the months that followed, when images of the corpses flashed before my mind’s eye, I would instinctively force them out, unable to look at them.

The ghosts of Jos appeared at the end of my hospital bed. The women who had been stuffed down a well. The old man with the broken neck. The baby – always the baby. Once the ghosts had arrived, they stayed. The psychiatrist and a therapist who had worked with the army – both of them wise and kind – set about treating what was diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A friend of mine, who has seen his share of horrors, devised a metaphor through which to better understand PTSD. He compares the brain to one of those portable golf holes with which golfers practise their putting. Normally the balls drop smoothly into the hole, one experience after another processed and consigned to memory. But then something traumatic happens – a car crash, an assault, an atrocity – and that ball does not drop into the hole. It rattles around the brain, causing damage. Anxiety builds until it is all-consuming. Vivid and visceral, the memory blazes into view, sometimes unbidden, sometimes triggered by an association – in my case, a violent film or anything that had been burned.

Steadfast family and friends kept me afloat. Mercifully, there were moments of bleak humour during my six weeks on the ward. When the BBC presenter welcoming viewers to coverage of the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton declared, ‘You will remember where you were on this day for the rest of your life,’ the audience of addicts and depressives in the patients’ lounge broke into a chorus of sardonic laughter and colourful insults aimed at the screen.

The treatment for PTSD is as simple as it is brutal. Like an arachnophobe who is shown a drawing of a spider, then a video of one, then gradually exposed to the real thing until he is capable of fondling a tarantula, I tried to face the memories from Jos. Armed only with some comforting aromas – chamomile and an old, sand-spattered tube of sunscreen, both evocative of happy childhood days – I wrote down my recollections of what I had seen, weeping onto the paper as my therapist gently urged me on. Then, day after day, I read what I had written aloud, again and again and again and again.

Slowly my terror eased. What it left behind was guilt. I felt I ought to suffer as those who died had – if not in the same way, then somehow to the same degree. The fact that I was alive became an unpayable debt to the dead. Only after months had passed came a day when I realized that I had to choose: if I were on trial for the slaughter at Jos, would a jury of my peers – rather than the stern judge of my imaginings – find me guilty? I chose peace, to let the ghosts rest.

It was not, however, a complete exoneration. I had reported that ‘ethnic rivalries’ had triggered the massacres in Jos, as indeed they had. But rivalries over what? Nigeria’s 170 million people are mostly extremely poor, but their nation is, in one respect at least, fabulously wealthy: exports of Nigerian crude oil generate revenues of tens of billions of dollars each year.

I started to see the thread that connects a massacre in a remote African village with the pleasures and comforts that we in the richer parts of the world enjoy. It weaves through the globalized economy, from war zones to the pinnacles of power and wealth in New York, Hong Kong and London. This book is my attempt to follow that thread.

A frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.

—WILLIAM BURROUGHS, Naked Lunch

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Introduction: A Curse of Riches

1. Futungo, Inc.

2. ‘It Is Forbidden to Piss in the Park’

3. Incubators of Poverty

4. Guanxi

5. When Elephants Fight, the Grass Gets Trampled

6. A Bridge to Beijing

7. Finance and Cyanide

8. God Has Nothing to Do with It

9. Black Gold

10. The New Money Kings

Epilogue: Complicity

Afterword

Picture Section

Footnote

Notes

List of Illustrations

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

A Curse of Riches

OPPOSITE THE New York Stock Exchange, at what the tourist information sign calls the ‘financial crossroads of the world’, the stately stone façade of 23 Wall Street evokes the might of the man whose bank it was built to house in 1913: J. P. Morgan, America’s capitalist titan. The exterior is popular with Hollywood – it doubled as the Gotham City stock exchange in the 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises – but when I visited in late 2013 the red carpet lay grubby and sodden in the drizzle blowing in off the Atlantic. Through the smeared glass in the shuttered metal gates, all that was visible in the gutted interior where once a vast chandelier glittered were a few strip lights, stairways covered in plywood, and a glowing red ‘EXIT’ sign.

Despite its disrepair, 23 Wall Street remains an emblem of the elite, a trophy in the changing game of global commerce. The address of its current owners is an office on the tenth floor of a Hong Kong skyscraper. Formerly the site of a British army barracks, 88 Queensway has been transformed into the mirrored towers of Pacific Place, blazing reflected sunlight onto the financial district. The sumptuous mall at street level, air-conditioned against the dripping humidity outside, is lined with designer boutiques: Armani, Prada, Chanel, Dior. The Shangri La hotel, which occupies the top floors of the second of Pacific Place’s seven towers, offers suites at $10,000 a night.

The office on the tenth floor is much more discreet. So is the small band of men and women who use it as the registered address for themselves and their network of companies. To those who have sought to track their evolution, they are known, unofficially, as ‘the Queensway Group’.1 Their interests, held through a web of complex corporate structure and secretive offshore vehicles, lie in Moscow and Manhattan, North Korea and Indonesia. Their business partners include Chinese state-owned corporations; BP, Total, and other Western oil companies; and Glencore, the giant commodity trading house based in a Swiss town. Chiefly, though, the Queensway Group’s fortune and influence flow from the natural resources that lie beneath the soils of Africa.

Roughly equidistant – about seven thousand miles from each – between 23 Wall Street in New York and 88 Queensway in Hong Kong another skyscraper rises. The golden edifice in the centre of Angola’s capital, Luanda, climbs to twenty-five storeys, looking out over the bay where the Atlantic laps at southern Africa’s shores. It is called CIF Luanda One, but it is known to the locals as the Tom and Jerry Building because of the cartoons that were beamed onto its outer walls as it took shape in 2008. Inside there is a ballroom, a cigar bar, and the offices of foreign oil companies that tap the prodigious reservoirs of crude oil under the seabed.

A solid-looking guard keeps watch at the entrance, above which flutter three flags. One is Angola’s. The second is that of China, the rising power that has lavished roads, bridges and railways on Angola, which has in turn come to supply one in every seven barrels of the oil China imports to fire its breakneck economic growth. The yellow star of Communism adorns both flags, but these days the socialist credentials of each nation’s rulers sit uneasily with their fabulous wealth.

The third flag does not belong to a nation but instead to the company that built the tower. On a white background, it carries three grey letters: CIF, which stands for China International Fund, one of the more visible arms of the Queensway Group’s mysterious multinational network. Combined, the three flags are ensigns of a new kind of empire.

In 2008 I took a job as a correspondent for the Financial Times in Johannesburg. These were boom times – or, at least, they had been. Prices for the commodities that South Africa and its neighbours possess in abundance had risen inexorably since the turn of the millennium as China, India and other fast-growing economies developed a voracious hunger for resources. Through the 1990s the average price for an ounce of platinum had been $470.2 A tonne of copper went for $2,600, a barrel of crude oil for $22. By 2008 the platinum price had tripled to $1,500, and copper was two and a half times more expensive, at $6,800. Oil had more than quadrupled to $95, and on one day in July 2008 hit $147 a barrel. Then the American banking system blew itself up. The shockwaves rippled through the global economy, and prices for raw commodities plunged. Executives, ministers and laid-off miners looked on aghast as the recklessness of far-off bankers imperilled the resource revenues that were Africa’s economic lifeblood. But China and the rest went on growing. Within a couple of years commodity prices were back to their pre-crisis levels. The boom resumed.

I traversed southern Africa for a year, covering elections, coups and corruption trials, efforts to alleviate poverty and the fortunes of the giant mining companies based in Johannesburg. In 2009 I moved to Lagos to spend two years covering west Africa’s tinderbox of nations.

There are plenty of theories as to the causes of the continent’s penury and strife, many of which treat the 900 million people and forty-eight countries of black Africa, the region south of the Sahara desert, as a homogenous lump.3 Colonizers had ruined Africa, some of the theorists contended, its suffering compounded by the diktats of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund; others considered Africans incapable of governing themselves, excessively ‘tribal’ and innately given to corruption and violence. Then there were those who thought Africa was largely doing just fine but that journalists seeking sensational stories and charities looking to tug at donors’ heartstrings distorted its image. The prescriptions were as various and contradictory as the diagnoses: slash government spending to allow private businesses to flourish; concentrate on reforming the military, promoting ‘good governance’ or empowering women; bombard the continent with aid; or force open African markets to drag the continent into the global economy.

As the rich world struggled with recession, pundits, investors and development experts began to declare that Africa, by contrast, was on the rise. Commercial indicators suggested that, thanks to an economic revolution driven by the commodity boom, a burgeoning middle class was replacing Africa’s propensity for conflict with rampant consumption of mobile phones and expensive whisky. But such cheery analysis was justified only in pockets of the continent. As I travelled in the Niger Delta, the crude-slicked home of Nigeria’s oil industry, or the mineral-rich battlefields of eastern Congo, I came to believe that Africa’s troves of natural resources were not going to be its salvation; instead, they were its curse.

For more than two decades economists have tried to work out what it is about natural resources that sows havoc. ‘Paradoxically,’ wrote Macartan Humphreys, Jeffrey Sachs and Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University in 2007, ‘despite the prospects of wealth and opportunity that accompany the discovery and extraction of oil and other natural resources, such endowments all too often impede rather than further balanced and sustainable development.’4 Analysts at the consultancy McKinsey have calculated that 69 per cent of people in extreme poverty live in countries where oil, gas and minerals play a dominant role in the economy and that average incomes in those countries are overwhelmingly below the global average.5 The sheer number of people living in what are some of the planet’s richest states, as measured by natural resources, is staggering. According to the World Bank, the proportion of the population in extreme poverty, calculated as those living on $1.25 a day and adjusted for what that wretched sum will buy in each country, is 68 per cent in Nigeria and 43 per cent in Angola, respectively Africa’s first and second-biggest oil and gas producers. In Zambia and Congo, whose shared border bisects Africa’s copperbelt, the extreme poverty rate is 75 per cent and 88 per cent, respectively. By way of comparison, 33 per cent of Indians live in extreme poverty, 12 per cent of Chinese, 0.7 per cent of Mexicans, and 0.1 per cent of Poles.

The phenomenon that economists call the ‘resource curse’ does not, of course, offer a universal explanation for the existence of war or hunger, in Africa or anywhere else: corruption and ethnic violence have also befallen African countries where the resource industries are a relatively insignificant part of the economy, such as Kenya. Nor is every resource-rich country doomed: just look at Norway. But more often than not, some unpleasant things happen in countries where the extractive industries, as the oil and mining businesses are known, dominate the economy. The rest of the economy becomes distorted, as dollars pour in to buy resources. The revenue that governments receive from their nations’ resources is unearned: states simply license foreign companies to pump crude or dig up ores. This kind of income is called ‘economic rent’ and does not make for good management. It creates a pot of money at the disposal of those who control the state. At extreme levels the contract between rulers and the ruled breaks down because the ruling class does not need to tax the people to fund the government – so it has no need of their consent.

Unbeholden to the people, a resource-fuelled regime tends to spend the national income on things that benefit its own interests: education spending falls as military budgets swell.6 The resource industry is hardwired for corruption. Kleptocracy, or government by theft, thrives. Once in power, there is little incentive to depart. An economy based on a central pot of resource revenue is a recipe for ‘big man’ politics. The world’s fourlongest-serving rulers – Teodoro Obiang Nguema of Equatorial Guinea, José Eduardo dos Santos of Angola, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, and Paul Biya of Cameroon – each preside over an African state rich in oil or minerals. Between them they have ruled for 136 years.

From Russia’s oil-fired oligarchs to the conquistadores who plundered Latin America’s silver and gold centuries ago, resource rents concentrate wealth and power in the hands of the few. They engender what Said Djinnit, an Algerian politician who, as the UN’s top official in west Africa, has served as a mediator in a succession of coups, calls ‘a struggle for survival at the highest level’.7 Survival means capturing that pot of rent. Often it means others must die.

The resource curse is not unique to Africa, but it is at its most virulent on the continent that is at once the world’s poorest and, arguably, its richest.

Africa accounts for 13 per cent of the world’s population and just 2 per cent of its cumulative gross domestic product, but it is the repository of 15 per cent of the planet’s crude oil reserves, 40 per cent of its gold and 80 per cent of its platinum – and that is probably an underestimate, given that the continent has been less thoroughly prospected than others.8 The richest diamond mines are in Africa, as are significant deposits of uranium, copper, iron ore, bauxite (the ore used to make aluminium), and practically every other fruit of volcanic geology. By one calculation Africa holds about a third of the world’s hydrocarbon and mineral resources.9

Outsiders often think of Africa as a great drain of philanthropy, a continent that guzzles aid to no avail and contributes little to the global economy in return. But look more closely at the resource industry, and the relationship between Africa and the rest of the world looks rather different. In 2010 fuel and mineral exports from Africa were worth $333 billion, more than seven times the value of the aid that went in the opposite direction (and that is before you factor in the vast sums spirited out of the continent through corruption and tax fiddles).10 Yet the disparity between life in the places where those resources are found and the places where they are consumed gives an indication of where the benefits of the oil and mining trade accrue – and why most Africans still barely scrape by. For every woman who dies in childbirth in France, a hundred die in the desert nation of Niger, a prime source of the uranium that fuels France’s nuclear-powered economy. The average Finn or South Korean can expect to live to eighty, nurtured by economies among whose most valuable companies are, respectively, Nokia and Samsung, the world’s top two mobile phone manufacturers. By contrast, if you happen to be born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, home to some of the planet’s richest deposits of the minerals that are crucial to the manufacture of mobile phone batteries, you’ll be lucky to make it past fifty.

Physical cargoes of African oil and ore go hither and thither, mainly to North America, Europe and, increasingly, China, but by and large the continent’s natural resources flow to a global market in which traders based in London, New York and Hong Kong set prices. If South Africa exports less gold, Nigeria less oil, or Congo less copper, the price goes up for everyone. Trade routes change: the increasing production of shale gas in the United States has reduced imports of Nigerian oil in recent years, for example, with the crude heading to Asia instead. But based on the proportion of total worldwide supply it accounts for, if you fill up your car fourteen times, one of those tanks will have been refined from African crude.11 Likewise, there is a sliver of tantalum from the badlands of eastern Congo in one in five mobile phones.

Africa is not only disproportionately rich in natural resources; it is also disproportionately dependent on them. The International Monetary Fund defines a ‘resource-rich’ country – a country that is at risk of succumbing to the resource curse – as one that depends on natural resources for more than a quarter of its exports. At least twenty African countries fall into this category.12 Resources account for 11 per cent of European exports, 12 per cent of Asia’s, 15 per cent of North America’s, 42 per cent of Latin America’s, and 66 per cent of Africa’s – slightly more than in the former Soviet states and slightly less than the Middle East.13 Oil and gas account for 97 per cent of Nigeria’s exports and 98 per cent of Angola’s, where diamonds make up much of the remainder.14 When, in the second half of 2014, commodity prices started to fall, Africa’s resource states were reminded of that dependency: the boom had led to a splurge of spending and borrowing, and the prospect of a sharp fall in resource rents made the budgets of Nigeria, Angola and elsewhere look decidedly precarious.

The resource curse is not merely some unfortunate economic phenomenon, the product of an intangible force; rather, what is happening in Africa’s resource states is systematic looting. Like its victims, its beneficiaries have names. The plunder of southern Africa began in the nineteenth century, when expeditions of frontiersmen, imperial envoys, miners, merchants and mercenaries pushed from the coast into the interior, their appetite for mineral riches whetted by the diamonds and gold around the outpost they had founded at Johannesburg. Along Africa’s Atlantic seaboard traders were already departing with slaves, gold and palm oil. By the middle of the twentieth century crude oil was flowing from Nigeria. As European colonialists departed and African states won their sovereignty, the corporate behemoths of the resource industry retained their interests. For all the technological advances that have defined the start of the new millennium – and despite the dawning realization of the damage that fossil fuels are inflicting on the planet – the basic commodities that lie in abundance in Africa remain the primary ingredients of the global economy.

The captains of the oil and mining industries, which comprise many of the richest multinational corporations, do not like to think of themselves as part of the problem. Some consider themselves part of the solution. ‘Half the world’s GDP is underpinned by resources,’ Andrew Mackenzie, the chief executive of the world’s biggest mining company, BHP Billiton, told a dinner for five hundred luminaries of the industry at Lord’s cricket ground in London in 2013. ‘I would argue: all of it is,’ he went on. ‘That is the noble purpose of our trade: to supply the economic growth that helps lift millions, if not billions, out of poverty.’15